|

THE SITTING BULL

INCIDENT

Unwelcome Visitors from

the United States Impose Several Years Hard Work and Grave

Responsibilities—The Great Sioux Leader and the Custer Massacre.

FEW more critical

positions were ever faced by a force entrusted with the preservation of

law and order in a country than that which confronted the North-West

Mounted Police when Sitting Bull, the Sioux leader, with his warlike and

powerful nation, after the so-called Custer massacre in the United

States, crossed the boundary line to seek shelter in Canadian territory.

Sitting Bull and his

warriors were flushed with a notable military success and liable to act

rashly. They were warlike, powerful and hard to control, and their

presence n Canada was a source of anxiety both to the Government of

Canada and that of the United States. These Indians harboured feelings

of fierce hostility towards, and thorough distrust of the United States

people and Government. These feelings could be traced to two principal

causes, the dishonesty of Indian agents and the failure of the U.S.

Federal authorities to protect the Indian reservations from being taken

possession of by an adventurous and somewhat lawless white population.

The officers of the North-West Mounted Police force were promptly

instructed to urge upon Sitting Bull and his warriors the necessity of

keeping the peace towards the people of the United States, but it was

felt to be not desirable to encourage them to remain on Canadian

territory. Colonel Macleod was accordingly instructed to impress them

with their probable future hardships, after the failure of the buffalo,

should they elect to remain in Canada; that the President of the United

States and his Cabinet were upright men, willing and anxious to do

justice to the Indians; and should they return peacefully, they would be

properly cared for, and any treaty made with them would be honestly

fulfilled. It was evidently desirable that as wards of the United States

they should return to that country upon the Government of which morally

devolved the burden and the responsibility of their civilization but how

could that end be attained?

Sitting Bull is

commonly thought of as a warrior. In point of fact he was not such. He

was a medicine man, which means that he included within himself the

three professions of the priesthood, medicine and law. He inherited from

his father the chieftainship of a part of the Sioux tribe; but his

remarkable ascendancy over the whole tribe or nation was due to his

miracle-working and to his talents as a politician. He played upon the

credulity of the Sioux with his "medicine", or pretended miracles, until

they believed him to possess supernatural powers, and were ready to

follow hi» lead in everything. Some other Sioux chiefs inherited wider

authority, and some minor chiefs were inclined now and then to dispute

his sway, but when Sitting Bull made an appeal to the religious

fanaticism of the people there was no withstanding him. As a medicine

man he had the squaws of the union abjectly subservient, and through

them was assisted in maintaining control of the bucks.

It might, perhaps, be

explained here that every Indian tribe in the old days had many medicine

men, some of them chiefs and important personages. Some were young,

others old, but they were all leaders in religious and social functions.

No one could visit an Indian tribe at any festival time, or period of

general excitement, without seeing the medicine men figuring very

conspicuously in whatever was going on. Sometimes they were merely

beating drums or perhaps only crooning while a dance or feast was in

progress. At other times they appeared in the most grotesque costumes,

painted all over, hung with feathers and tails and claws, and carrying

some wand or staff, gorgeous with colour and smothered with Indian

finery. The medicine man was a conjurer, a magician, a dealer in magic,

and an intermediary between the men of this world and the spirits of the

other. He usually knew something, often a great deal, of the rude

pharmacopoeia of his fellows, and occasionally, prescribed certain

"leaves or roots to allay a fever, to arrest a cold or to heal a wound.

That was not his business, however, and such prescriptions were more apt

to be offered by the squaws. The term medicine man" is simply a white

man's expression which the Indians have adopted. It was originally used

by the white explorers and missionaries because they found these tribal

priests or magicians engaged in their incantations at the sides of the

sick, the wounded, or dying. But instead of being engaged in the

practice of medicine the so-called "medicine men" were in reality

exorcising the evil spirits of disease or death. - Sitting Bull was born

about 1830 and was the son of Jumping Bull, a Sioux chief. His father

was, for an Indian, a wealthy man. Sitting Bull, although not intended

for a warrior, as a boy was a wonderfully successful hunter, and at

fourteen years of age he fought and killed another Indian considerably

older than himself, receiving a wound, which made him lame for life. He

first became widely known to the white people of America in 1860, in

that year leading a terrible raid against the settlers and U.S. military

post at Fort Buford. His path was marked with blood and made memorable

by ruthless savagery. As the marauders approached the fort, the

commandant of the post shot and killed his own wife at her earnest

request, to save her from the more cruel fate of falling into the hands

of the Sioux.

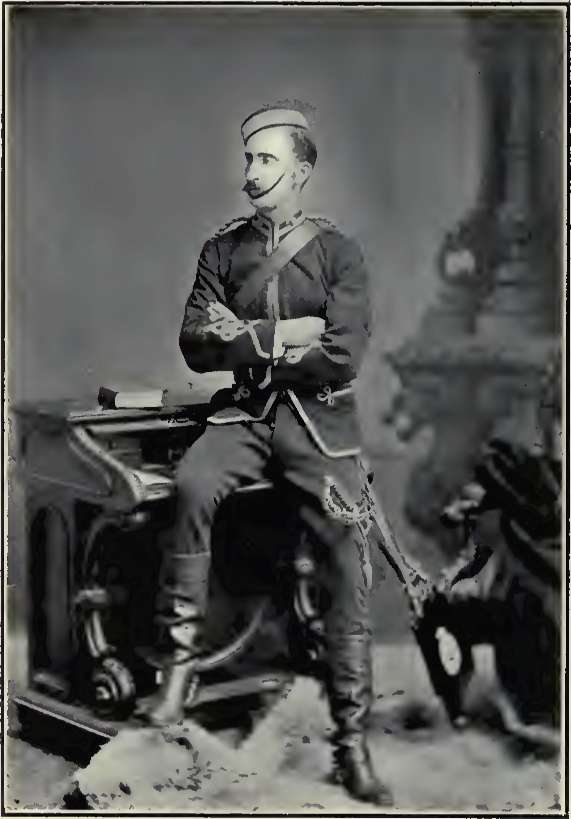

Sioux Leader "Sitting-Bull." (Ta-Ton-Ka-I-A-Ton-Ka.)

In the early '70's

Sitting Bull set up a claim to all the land for forty rods on both sides

of the Yellowstone and all its tributaries. In the latter part of 1875 a

party of fifty white men from Montana invaded Sitting Bull's territory

and built a fort. The Indians were determined that the party should

evacuate, and during the months of December 1875 and January

1876 there were daily

attacks upon the fort. A strong force of United States regulars and

Montana militia was sent to the relief of the place, the occupants of

the forts were taken away, and Sitting Bull promptly fired the place.

Sitting Bull reached the zenith of his fame and power the succeeding

summer.

Gold and silver had

been discovered in the Black Hills, in the district which was not only

regarded by the Indians as peculiarly their own, but in a certain sense

as a "medicine" or sacred region. There was a great rush of miners and

prospectors to the country immediately, and it was one of these parties

that established the fort which Sitting Bull had caused the evacuation

of. Several great Indian chiefs visited Washington to protest against

the invasion of the prospectors, which they pointed out was a clear

violation of existing treaties between the Indians and the United States

Government. The Washington officials agreed to keep the prospectors out

but failed to do so, and by the autumn of 1875 there were a thousand

miners at work in the Black Hills. Then the Indians demanded payment for

the land of which they were being deprived, and a Government commission

was sent to the spot to arrange matters. But the commission returned and

reported that there was no use trying to arrange matters without force

to enforce the terms. This convinced many of the Indians that the best

thing they could do was to fight for their rights, and singly and by

villages, they gradually deserted from Red Cloud, Spotted Tail and the

other more peacefully disposed chiefs, and began flocking to Sitting

Bull, who had all along been truculent and had opposed all suggestions

to abandon the title of the Indians to the territory in question. At the

time, he was roaming about in the northern part of Dakota, near the

Canadian frontier. Anticipating serious trouble, the United States

authorities during the autumn of 1875 sent word to Sitting Bull and the

chiefs with him that they must report at the reservations allotted to

them by the 1st of January 187G, the alternative being war. The threat

having no effect, and a winter campaign having been attempted and found

unsatisfactory, a vigorous campaign was organized in the spring. Three

columns under the command of Generals Gibbon, Terry and Crook were

equipped and placed under inarching orders, the objective point being

Sitting Bull's camp in the Big Horn country. With General Terry's

column, destined to march westward from Fort Lincoln, was the 7th United

States Cavalry, under the dashing young General Custer, who had been

such a picturesque figure in the final stages of the Civil war, and who

had performed many daring things in Indian warfare during the years

which succeeded the triumph of the Northern cause.

June 22, Custer at the

head of his fine regiment of twelve companies, left the divisional camp

at the mouth of the Rosebud to follow a heavy trail leading up the river

and westward in the direction of the Big Horn, the expectation being

that the hostile force would be struck near the eastern branch of the

last named river, and known as the Little Big Horn. General Terry with

the rest of his force started to ascend the Yellowstone by steamer,

thence marching up the bank of the Big Horn. It was estimated that both

columns would be with n striking distance of the hostiles and able to

co-operate by the 2(ith. But 011 the 25th Custer's force was involved in

an awful disaster.

Comparatively

unexpectedly Custer struck Sitting Bull's camp in the valley of the

Little Big Horn while three of Ins companies were detached two miles on

his left flank, and one to his rear. Without taking any care to properly

reconnoitre the hostile position, to ascertain the exact location and

strength, he decided to attack at once, and with characteristic

Anglo-Saxon disregard of Indians, recklessly divided his force,

detailing Major Reno with three companies to attack the position from

the direction of the original advance, while he himself, with five

companies, made a detour of some three miles to take the hostiles in

flank or rear. Reno's command found themselves so outnumbered that,

after some heavy fighting and losing many men, they were forced to

withdraw to a high bluff, where after entrenching themselves, they were

able to hold their own until joined by the four companies which had been

detached. Custer and his immediate command literally plunged headlong

and recklessly into the very strongest part of the Indian position and

were literally annihilated, not one officer, non-commissioned officer or

man of those five gallant companies surviving the massacre to tell the

tale, although all sold their lives dearly, fighting to the very last.

Reno and his force succeeded in holding their own in their entrenched

position against the repeated and desperate attacks of the Indians until

relieved on the 27th by General Terry.

For some weeks the

United States troops supposed that Sitting Bull had been killed in the

fight with Custer's force, but in course of time reports from the wild

country in the north of the state near the Canadian frontier showed that

he was alive, and military operations were resumed. In May, 1877,

reports from Canada, through the North-West Mounted Police, announced

that the old leader, with many of his warriors, had taken refuge across

the International frontier.

As early as May, 1870,

the Mounted Police had been keeping a sharp lookout for bands of

fugitive Indians from across the lines. The Assistant Commissioner,

Lieut.-Col. Irvine, in temporary command of the Force during the

Commissioner's absence in the east, in the summer, instructed Inspector

Crozier, in command at Cypress Hills, to even gather all the information

he could regarding the movements of the Sioux Indians on the United

States side of the line.

During December, 1876.

United States Indians, under Black Moon, an Unapapa Sioux chief,

numbering about 500 men, 1,000 women, and 1,400 children, with about

3,500 horses and 30 United States government mules, crossed the line,

and encamped at Wood Mountain, east of the Cypress Hills. Sub-Inspector

Frechette having located this camp. Inspector Walsh proceeded thither,

arriving at Wood Mountain on the 21st December, making the trip from the

end of the Cypress Mountain in three and one-half days. I he hostiles

had arrived only two days before the Inspector's arrival. Their camp was

adjoining the .Santee camp of about 150 lodges, of which White Eagle was

the Chief, and was situated in the timber, four miles east of the

Boundary Survey Buildings. White Eagle had occupied that section for

many years past, and was \er observant of the Canadian laws, lie

expressed himself to be glad to see Inspector Walsh, as he was unable to

tell the new arrivals the laws which they would have to observe if they

remained in this country. The matter had given him much uneasiness as he

did not wish other Indians coming in and joining his camp to be without

a knowledge of the law which would govern them. About six o'clock on the

evening of Walsh's arrival, White Kagle assembled all the hostile

Chiefs; the principal ones amongst whom were "The Little Knife," "Long

Dog," "Black Moon," and "The Man who Crawls," and explained to them who

the Inspector was.

Walsh opened the

Council by telling them he would not say much to them aside from giving

them the laws which governed the people in Canada, which they must obey

as long as they remained, and to ask them a few questions to which

answers would be required, which, he would transmit to the Queen's Great

Chief in the country.

He asked them the

following questions: "Do you know that you are in the Queen's country"?

They replied, that they had been driven from their homes by the

Americans, and had come to look for peace. They had been told by their

grandfathers that they would find peace in the land of the British.

Their brothers, the Santees, had found it years ago and they had

followed them. They had not slept sound for years, and were anxious to

find a place where they could lie down and feel safe; they were tired of

living in such a disturbed state.

Walsh next asked them,

"Do you intend to remain here during the cold months of winter, have

peace, and when spring opens, return to your country across the line and

make war?" They answered, no, they wished to remain, and prayed that he

would ask the Great Mother to have pity on them.

Walsh then explained

the laws of the country to them as had been the police custom in

explaining them to other Indians, and further told them they would have

to obey them as the Santees and other Indians did.

The several chiefs then

made speeches in which they implored the Queen to have pity on them, and

they would obey her laws. Walsh replied that he would send what they had

said to the Queen's Great Chief. In conclusion he told them there was

one thing they must bear in mind, the Queen would never allow them to go

from her country to make war on the Americans, and return for her

protection, and that if such were their intentions they had better go

back and remain.

The following day the

Chiefs waited upon Walsh, with White Eagle for spokesman, and prayed

that he would allow them a small quantity of ammunition for hunting

purposes as their women and children were starving. They were using

knifes made into lances for hunting buffalo, and others were lassoing

and killing them with their knives. Some were using bows and arrows, and

killing this way was so severe on their horses that they were nearly

used up, and if they did not have any ammunition they must starve.

Walsh replied that the

Great Mother did not wish any people in her country to starve, and if

she wras satisfied that they would make no other use of ammunition other

than for hunting, she would not object to them having a small quantity,

and that the Santees who had always obeyed the laws could be allowed a

small quantity; but they, the Uncapapa's Agallallas and others were

strangers, and might want ammunition to send to the people whom they

claimed as brothers on the other side of the line. This, they declared

they did not wish to do.

Walsh then told them he

would meet Mr. Le Garre, a Wood Mountain trader, who was on his way with

some powder and ball and 2,000 rounds of improved ammunition to trade to

the Santees, and would allow him to trade to them a small quantity for

hunting purposes only, and this appeared to relieve them greatly.

Not the least cause of

anxiety in connection with the incursion of these United States Indians

was the fear of collision with the Canadian tribes. In his report at the

end of the year 1876, the Comptroller, Mr. White, wrote:—"The country

betwteen the Cypress Hills and the Rocky Mountains, which has hitherto

been claimed by the Blackfeet as their hunting ground, has this year

been encroached upon by other Indians and Half-breeds, causing much

irritation among the Blackfeet, who have called upon the Police to

protect them in maintaining their rights to their territory, saying that

if they were not restrained by the presence of the Police, they would

make war upon the intruders."

According to the

Commissioner's report, for 1877, the state of affairs existing during

the early part of that year in the southwesterly districts of the

North-West Territories, was entirely different from any experienced

since the arrival of the Force in the country. The winter was extremely

mild, week following week with the same genial sunshine, the mild

weather being interrupted only by an occasional cold day. There was

little or no snow, so that the grass of the prairie from one end to the

other, being dried up easily, took fire, and only required a spark to

set it ablaze for miles in every direction. Unfortunately, nearly all

the country out from the mountains, the favorite haunt of buffalo during

the winter season, was burnt over, so that from this cause, and also on

account of the mild weather, the herds did not go into their usual

winter feeding ground; but remained out in the plains to the north and

south of the Saskatchewan. The Blackfeet Indians who had as usual moved

up towards the mountains in the fall, and formed their camp along the

river bottoms, which had for years back afforded them fuel and shelter,

and easy access to a supply of meat, were forced to take long journeys

of seventy and one hundred miles, to secure the necessary supply of food

for themselves and families, and eventually moved their camps out to

where buffalo were to be got, with the exception of few small camps, who

were in an almost star\ing condition several times during the winter.

The result of this

condition of things was a large band of Blackfeet were gradually getting

closer and closer to the Sioux, who were, by degrees, making their way

up from the south-east in pursuit of buffalo, while other bands of

Indians and half-breeds were pressing in both from the north and south.

The most extravagant rumors were brought in from all directions. A grand

confederation of all the Indians was to be formed hostile to the whites,

every one of whom was to be massacred as the first act of confederation.

"Big Bear," a non-treaty Cree Indian chief, was said to be fomenting

trouble amongst the Indians on the Canadian side. An officer, Inspector

Crozier, whom the Commissioner sent to inquire into the matter, was told

that he would not get out of Big Bear's camp alive.

The police officers

felt quite confident the reported confederation was without foundation.

And so far as the Blackfeet were concerned, their loyalty had been made

firmer than ever by the treaty which had been very opportunely made the

autumn before. The Commissioner, in fact, had often received assurances

of their support in case the Force got into trouble with the Sioux, and

he could never trace the reports of disaffection amongst the Canadian

Indians to any reliable source. Even "Big Bear," who had a bad

reputation, when visited by Inspector Crozier, repudiated any intention

of behaving as had been reported.

On account of the large

gathering of Indians of different tribes, the Commissioner deemed it

advisable to recommend the concentration of as large a force as possible

at Fort Walsh, the post nearest to where the Indians would be

congregated. The Canadian Indians had frequently expressed a desire that

some of the police should be near them during the summer, when they were

out on the plains. The Commissioner thought that the presence of a

strong force at Fort Walsh might strengthen the hands of the Canadian

Indians, who were very jealous of the intrusion of the Sioux, and might

be the means of checking any disturbance which might occur.

Happily the year passed

over without any signs of the rumored alliance of the Indians against

the whites, and there were no signs of any disaffection on the part of

the Canadian Indians. They had visited and mixed with the Sioux, and the

Sioux with them, and there was no reason to think that those visits had

meant anything more than a desire to make peace with one another, as

they had been enemies for years before. "Crow Foot." the leading chief

of the Blackfeet, told the Commissioner that he had been visited by

Sitting Bull who told him he wished for peace. Crowfoot had replied that

he wanted peace; that he was glad to meet the Sioux leader 011 a

friendly visit, but that he did not wish to camp near him, or that their

people should mix much together in the hunt, and it was better for them

to keep apart.

Immediately after the

first party of Sioux crossed the lines in December, 1876, communication

between Fort Walsh and the Indian Camps was established by the erection

of outposts convenient distances apart. The police took possession of

all firearms and ammunition held by parties for the purpose of trade,

and sales were only allowed in that region on permits granted by the

officers of the Force.

Early in March,

Medicine Bear and his tribe of Yanktons (300 lodges) crossed into

Canadian territory, and also Four Horns, the head-chief of the Tetons,

with 57 lodges direct from Powder River. Inspector Walsh held a council

with the new arrivals on March 3rd, at their camp on the White Mud

River, 120 miles east of Fort Walsh.

These chiefs set up the

claim that all the Sioux tribes were British Indians. From child-hood

they had been instructed by their fathers that properly they were

children of the British, and in their tribes were many of the medals of

their "White Father", (George III), given to their fathers for fighting

the Americans. Sixty- five years previously, was the first their fathers

knew of being under the Americans, but why the "White Father" gave them

and their country to the Americans they could not tell. Their fathers

were told at the time by a chief of their "White Father" that if they

did not wish to live with the Americans they could move northward and

they would again find British land there.

Towards the end of May,

Sitting Bull, with his immediate tribe, crossed the boundary and joined

the other Suited States Indians in Canadian Territory.

Inspector Walsh

promptly had an interview with Sitting Bull, Bear's Head and several

other Chiefs. They asked for ammunition, and Inspector Walsh informed

them that they would be permitted to have sufficient to kill meat for

their families, but cautioned them against sending any across the line.

They also made the claim that their grandfathers were British, and that

they had been raised on the fruit of English soil. Inspector Walsh

explained the law to them, and asked Sitting Bull if he would obey it.

He replied that he had buried his arms on the American side of the line

before crossing to the country of the White Mother. When he wanted to do

wrong, he would not commit it in the country of the White Mather, and if

in future he did anything wrong on the United States side, he would not

return to this country any more. He also said he had been fighting 011

the defensive; that he came to show us that he had not thrown this

country away, and that his heart was always good, with the exception of

such times as he saw an American. Inspector Walsh, from the interview,

gathered that Sitting Bull was of a revengeful disposition, and that if

he could get the necessary support he would recross the line and make

war on the Americans.

May 29, Lieut.-Colonel

Irvine, the Assistant Commissioner arrived at Fort Walsh, and shortly

after his arrival, six young warriors arrived from Sitting Bull's camp

to report that three Americans had arrived there. On the morning of the

31st, the Assistant Commissioner started for the camp, (140 miles due

east) accompanied by Inspector Walsh and Sub-Inspectors Clark and Allen.

Irvine was much impressed with Sitting Bull. He found the Indians very

bitter towards the three men in their camp for following them, regarding

them as spies. The three were Reverend Abbott Martin, a Roman Catholic

missionary, General Miles' head scout and an army interpreter. But for

Sitting Bull's promise to Walsh, the two latter, who were known to the

Indians, would have been shot. The object of the priest was simply to

try and induce the Indians to return to their agencies. The army men

claimed that they had accompanied the priest for protection, but that

their object was to ascertain from the Mounted Police, if the Indians

intended to return.

The council between

Irvine and Sitting Bull was conducted with impressive ceremony. The

peace pipe was smoked, the ashes taken out and solemnly buried, and the

pipe was then taken to pieces and placed over the spot.

Sitting Bull had around

him Pretty Bear, Bear's Cap, The Eagle Sitting Down, Spotted Eagle,

Sweet Bird, Miracongae, &c., &c.; and in the Council Lodge there must

have been some hundred men, women and children.

Inspector Walsh

informed Sitting Bull and the chiefs that Lieut.-Col. Irvine was the

highest chief of the Great Mother at present in the country, and that he

had now come to their camp to hear what they had to say to him, and to

learn for what purpose the three Americans who at present were in the

camp had come from United States to Canadian territory to their camp.

Lieut.-Col. Irvine,

addressing the Indians through an interpreter remarked:—"You are in the

Queen's, the Great Mother's country. Major Walsh has explained the law

of the land which belongs to the Great White Mother. As long as you

remain in the land of the Great White Mother, you must obey her laws. As

long as you behave yourselves, you have nothing to fear. The Great White

Mother, the Queen, takes care of everyone in her land in every part of

the world.

"Now that you are in

the Queen's land you must not cross the line to fight the Americans and

return to this country. We will allow you enough ammunition to hunt

buffalo for food, but not one round of that ammunition is to be used

against white men or Indians.

"In the Queen's land we

all live like one family. If a white man or Indian does wrong he is

punished. The Queen's army is very strong, and if any of her children do

wrong she will get them and punish them. If anyone comes into your camp

like those Americans did, come to the Fort and tell Major Walsh. You are

quite right, and I am glad you did send your young men to tell Major

Walsh about these men. As soon as your young men arrived at the Fort, we

started, and I came here to see you and shake hands. I will go to see

those Americans and find out what they are doing here, and will take

them out of the camp with me. I am glad you are looking for peace and

behaving yourselves here. We will protect you against all harm, and you

must not hurt anyone this side of the line. You were quite right not to

hurt the Americans who came here and to send to Major Walsh. You need

not be alarmed. The Americans cannot cross the line after you. You and

your families can sleep sound and need not be afraid."

Lieut.-Col. Irvine was

somewhat surprised at receiving a visit in his tent from Sitting Bull

after eleven that night. He sat on the Assistant Commissioner's bed

until an early hour in the morning, telling him in a subdued tone his

many grievances against the "Long Knives."

At first Sitting Bull's

party in Canadian territory numbered 135 lodges, but it rapidly

augmented.

It was astounding with

what rapidity the news of Sitting Bull's safe arrival in Canada was

transmitted to other branches of Sioux who had, up to that time,

remained in the United States. This news quickly had the effect of

rendering the North-West Territories attractive to the remainder of the

hostile Indians who had taken part in the Custer fight, their numbers

being augmented by large bands of Indians of the same tribes who

previously had been located in United States reservations—in other

words, a general stampede took place, and in an extremely short time

Canada became the home of every Sioux Indian who considered himself

antagonistic to the United States Government. In all, they numbered some

700 lodges; these lodges being crowded, it may safely be estimated that

they contained eight souls to a lodge; thus suddenly the Xorth-West had

its Indian population increased in a very undesirable manner by some

five thousand souls. In addition to Sitting Bull, the Mounted Police had

such celebrated chiefs as "Spotted Eagle," "Broad Trail," "Bear's Head,"

"The Elving Bird," " The Iron Dog," "Little Knife," and many others to

deal with.

Not only were the fears

of actual and intending settlers aroused, but our own Indians and

Half-breeds looked with marked, and not unnatural, disfavour upon the

presence of so powerful and savage a nation (for such it really was) in

their midst. Canadians were assured on all sides that nothing short of

an Indian war would be on our hands; to add to this, serious

international complications at times seemed inclined to present

themselves. Both the United States and Canadian press kept pointing out

the possibility of such a state of affairs coming about.

The press of Manitoba

urged that a regiment of mounted troops, in addition to the police,

should be sent to the North-West to avoid international complications

and the interruption of trade.

The matter was even

referred to by Major General Selby Smith ii his annual report on the

Canadian Militia for the year 1877, he, writing:

"The recent addition to

the Indian population of the prairies, by the arrival of a large body of

Sioux under the notorious Chief 'Sitting Bull', at Cypress Hills, calls

for increased precautions and strength; and especially for the greatest

possible efficiency of the North-West Mounted Police. From my personal

experience of this valuable body of men I can speak m high terms of

approval. In my report subsequent to my journey through the North-West

Territories two years ago, I ventured to recommend a depot and training

establishment in Ontario for officers, men and horses of the North-West

Mounted Police, to be an obvious necessity; to spend six months for

instructions before joining their troops so widely detached over the

spacious region of those pathless prairies."

As early as May 30,

1877, Lieut.-Col. Macleod, the Commissioner, then in Ottawa, n a report

to the Prime Minister, the lion Alex. Mackenzie, arid the Secretary of

State, the Hon. R. W. Scott, explained that both Rlackfeet and Crees

were anxious about the invasion of their territory by the Sioux. The

Blackfeet had remembered that before the police took possession of the

country for Canada they had been always able to keep them out. The

Commissioner strongly advised that an attempt be made to induce the

Sioux to recross to the United States side. He recommended that the

United States Government be corresponded with and their terms submitted

to the Sioux, who would be told that they could not be recognized as

British Indians, that no reserves could be set apart for them in Canada,

and no provision made for their support by the Government; and moreover,

that by remaining on the Canadian side they would forfeit any claim they

had on the United States.

August 15, 1877, the

Hon. R. W. Scott, Secretary of State, telegraphed Lieut-Col. Macleod,

then at Fort Renton, Mont., as follows:—

"Important that Sitting

Bull and other United States Indians should be induced to return to

reservations. United States Government have sent Commissioners to treat

with them. Co-operate with Commissioners, but do not unduly press

Indians.

"Our action should be

persuasive, not compulsory.

"Commissioners will

probably reach Benton about 25th inst. Arrange to meet them there."

The commission referred

to in the preceding, appointed by the President of the United States,

consisting of Generals Terry and Lawrence, was sent to Fort Walsh, in

which vicinity the Sioux were, to endeavour to induce the refugees to

return to the United States. The commissioners and their party arrived

at the Canadian frontier on October 15th and we e there met bv an escort

of the Mounted Police, who accompanied them until their return to United

States territory. The next day after crossing the boundary the

commission arrived at Fort Walsh, where Major Walsh of the Police, under

instructions from head quarters, issued at the instance of the

Commissioners, had induced Sitting Bull to come. The following day a

conference was held between the commissioners and Sitting Bull, who was

accompanied by Spotted Tail and a number of his other chiefs.

General Terry told

Sitting Bull through his interpreters that Ins was the only Indian baud

which had not surrendered to the United States. He proposed that the

band should return and settle at the agency, giving up their horses and

arms, which would be sold and the money invested in cattle for them.

Sitting Bull replied:

"For sixty-four rears

you have kept me and my people and treated us bad, What have we done

that you should want us to stop? We have done nothing. It is all the

people on your side that have started us to do all these depredations.

We could not go anywhere else, and so we took refuge in this country. It

was on this side of the country we learned to shoot, and that is the

reason why I came back to it again. I would like to know why you came

here. In the first place, I did not give you the country, but you

followed me from one place to another, so I had to leave and come over

to this country. I was born and raised in this country with the Red

River half-breeds, and I intend to stop with them. I was raised

hand-in-hand with the Red River half-breeds,

Superintendent J. M. Walsh.

and we are going over

to that part of the country, and that is the reason why I have come over

here. (Shaking hands with Col. Macleod and Major Walsh.) That is the way

I was raised, in the hands of these people here, and that is the way I

intend to be with them. You have got ears, and you have got eyes to see

with them, and you see how I live with these people. You see me? Here I

am! If you think I am a fool, you are a bigger fool than I am. This

house is a medicine house. You come here to tell us lies, but we don't

want to hear them! I don't wish any such language used to me ; that is,

to tell me such lies, in my Great Mother's (the Queen's) house. Don't

you say two more words. Go back home, where you came from. This country

is mine, and I intend to stay here, and to raise this country full of

grown people. See these people here? We were raised with them. (Again

shaking hands with the police officers.) That is enough; so no more. You

see me shaking hands with these people. The part of the country you gave

me you ran me out of. I have now come here to stay with these people,

and I intend to stay here. I wish to go back, and to 'take it easy'

going back. [Taking a Santee Indian by the hand.] These Santees—I was

born and raised with them. He is going to tell you something about

them."

"The-one-that-runs-the-roe," a Santee Indian, said: "Look at me! I was

born and raised in this country. These people, away north here, I was

raised with—my hands in their own. I have lived in peace with them. For

the last sixty-four years we were over in your country, and you treated

us badly. We have come over here now, and you want to try and get us

back again. You didn't treat us well, and I don't like you at all."

A squaw with the

peculiar appelation "The-one-that-speaks-once" then spoke, remarking:—"I

was over in your country; I wanted to raise my children over there, but

you did not give me any time. I came over to this country to raise my

children and have a little peace. (Shaking hands with the police

officers.) That is all I have to say to you. I want you to go back where

you came from. These are the people I am going to stay with, and raise

my children with."

"The Flying Bird" then

made a speech and said:

"These people here, God

Almighty raised us together. We have a little sense and we ought to love

one another. Sitting Bull here says that whenever you found us out,

wherever his country was, why, you wanted to have it. It is Sitting

Bull's country, this is. These people sitting all around me: what they

committed I had nothing to do with. 1 was not in it. The soldiers find

out where we live, and they never think of anything good; it is always

something bad." (Again shaking hands with the police officers.)

The Indians having

risen, being apparently about to leave the room, the interpreter wigs

then directed to ask the following questions:

"Shall I say to the

President that you refuse the offers that he has made to you? Are we to

understand from what you have said that you refuse those offers?"

Sitting Bull.—"I could

tell you more, but that is all I have to tell you. If we told you

more—why you would not pay any attention to it. That is all I have to

say. This part of the country does not belong to your people. You belong

to the other side; this side belongs to us."

And so the commission

returned to the United States without having accomplished anything.

After the interview of

the United States Commissioners with the Indians, Col. Macleod had a

"talk" with the latter. He endeavoured to impress upon them the

importance of the answer they had just made; that although some of the

speakers to the Commissioners had claimed to he British Indians, the

British denied the claim, and that the Queen's Government looked upon

them all as United States Indians who had taken refuge in Canada from

their enemies. As long as they behaved themselves the Queen's Government

would not drive, them out, and they would be protected from their

enemies, but that was all they could expect.

It is hard to realize

the awkward position in which the Police Force was placed. From 1877 up

to 1881 the force maintained a supervision and control of the refugee

Sioux. It would take chapters to give even a short summary of the

perpetual state of watchfulness and anxiety the force was kept in during

these years, to say nothing of the hard service all ranks were

constantly being called upon to perform. Every movement of the Sioux was

carefully noted and reported upon. The severity of the North-West winter

was never allowed to interfere in the slightest degree with the police

duty it was considered necessary to perform.

Many reports, official

and semi-official, were forwarded through various channels on what was

considered the vexed "Sioux question."

At one time many people

were of the opinion that Sitting Bull and his band of immediate

followers would never be induced to surrender to the United States, the

impression being that these undesirable settlers were permanently

located in our territories.

Through the officers of

the force, however, negotiations were carefully carried on with the

Sioux. Besides the basic difficulties to be overcome, the intricate and

delicate manner with which the officers had to deal with even the

smallest details relating to the ultimate surrender necessitating the

exercise of great caution. Many complications arose, all of which

delayed materially the surrender so much desired and eventually

effected. Among other things a questionable and discreditable influence

was brought to bear by small traders and others in anticipation of

inducing the Sioux to remain n Canada.

While the qualities of

patience and diplomacy possessed by the Mounted Police were being tried

to the utmost with the refugee Indians from across the lines, they were

encouraged by several evidences of the confidence n and respect for them

shown by the Canadian Indians.

During the. year 1877,

one of the band of Mecasto, head chief of the Bloods, confined in the

Police Guard Room at Macleod on a charge of theft, escaped across the

lines. Some time afterwards he returned to Mecasto's camp, and the chief

at once apprehended him. and with a large number of his warriors,

delivered him up at the fort gate to the officer in command.

An incident of trouble

between Canadian Indians at this time is interesting as indicating the

pluck shown by the police in dealing with the Indians.

May 25, 1877, Little

Child, a Sauteaux Treaty Chief, arrived at Fort Walsh and reported that

the Sauteaux, numbering 15 lodges, and 250 lodges of

Superintendent Crozier.

Assiniboines, were

camped together at the northeast end of Wood Mountain. On the 24th, the

Sauteaux camp concluded to move away from the Assiniboines. consequently

they informed the Assiniboines of their intention. An Assiniboine named

( row's Dance had formed a war lodge, and gathered about 200 young men

as soldiers under him. It appears Crow's Dance gave orders that no

person was to move away from the camp without the permission of his

soldiers.

Little Child was

informed that the Sauteaux could not leave; that if they persisted in

doing so the soldiers would kill their horses and dogs, and cut their

lodges, etc. Little Child replied if they did him any harm or occasioned

any damage to his people, he would report the matter to the Police.

Crow's Dance replied, "We care as little for the Police as we do for

you."

Little Child then had a

Council with his head men, and addressed them as follows: "We made up

our minds to move but are forbidden. When the children of the White

Mother came to the country we thought they would protect us to move

wherever we pleased, as long as we obeyed her law, and if any one did us

any harm we were to report to them. This is the first time that any such

an occurrence has happened since the arrival of the Police in the

country; let us move; let the Assiniboines attack us, and we will report

to the. ' White Mother's Chief,' and see if he will protect us."

To this they all

assented and the camp was ordered to move. The lodges were pulled down,

and as they attempted to move off. between two and three hundred

warriors came down on the camp and commenced firing with guns and bows

in every direction, upsetting travois cutting lodges, etc., besides

killing nineteen dogs (a train dog supplied the place of a horse to an

Indian) knocking men down and threatening them with other punishment?

The women and children ran from the camp, screaming and crying. It seems

only by a miracle that no serious damage was done with the fire-arms, as

the warriors fired through the camp recklessly. When warned by Little

Child that he would report the matter to the Police, Crow's Dance struck

him and said: "We will do the same to the Police when they come".

After the attack was

over Little Child and camp moved northwards, and the Assiniboines toward

the east. At 11 a.m., Inspector Walsh started with Inspector Kittson,

fifteen men and a guide, to arrest Crow's Dance and his head men. At 10

p.m. the party arrived at the place where the disturbance occurred and

camped. At 2 a.m., they were again on the road, a march of about 8 miles

brought them in sight of the camp. The camp was formed in the shape of a

war camp with a war lodge in the centre. In the "war lodge" Walsh

expected to find the head soldier, Crow's Dance, with his leaders.

Fearing they might,

offer resistance, as Little Child said they certainly would, Walsh

halted and had the arms of his men inspected, and pistols loaded.

Striking the camp so early, he thought he might take them by surprise.

So he moved west, along a ravine, about half a mile; this bringing him

within three-fourths of a mile of the camp. At a sharp trot the

detachment soon entered camp and surrounded the war lodge, and found

Crow's Dance and nineteen warriors in it. Walsh had them immediately

moved out of cam]) to a small butte half a mile distant; found the

lodges of the Blackfoot and Bear's Down; arrested and took them to the

butte. It was now 5 a.m., and Walsh ordered breakfast and sent the

interpreter to inform the chiefs of the camp that he would meet them in

council in about an hour. The camp was taken by surprise, the arrests

made and prisoners taken to the butte before a Chief in the camp knew

anything about it.

Inspector E. Dalrymple Clark, First Adjutant of the North-West Mounted

Police.

At the appointed time

the following Chiefs assembled, viz., "Long Lodge," "Shell King" and

"Little Chief". Walsh told them what he had done, and that he intended

to take the prisoners to the fort and try them by the law of the White

Mother for the crime, they had committed; that they, as chiefs, should

not have allowed such a crime to be committed. They replied, they tried

to stop it lint could not. Walsh then said he was informed there were

parties in the camp at that moment who wished to leave, but were afraid

to go; that these parties must not be stopped; and for them (the chiefs)

to warn their soldiers never in future to attempt to prevent any person

leaving camp; that according to the law of the White Mother even- person

had the privilege of leaving camp when they chose. At 10 a.m., Walsh

left the Council, and arrived at Fort Walsh at 8 p.m., a distance of 50

miles.

Before entering the

camp, Walsh explained to his men that there were two hundred warriors in

the camp who had put the Police at defiance; that he intended to arrest

the leaders; but to do so perhaps would put them in a dangerous

position, but that they would have to pay strict attention to all orders

given no matter how severe they might appear. Walsh afterwards reported

that from the replies and the way his men acted during the whole time,

he was of opinion that every man of this detachment would have boldly

stood their ground if the Indians had made any resistance.

Sitting Bull then

strove to bring forward some pretext by which he and his followers might

remain on Canadian soil. Finally, recognizing that nothing beyond right

of asylum would be afforded him, this once mighty chief left the Wood

Mountain Post for the purpose of surrendering to the United States

authorities at Fort Bulford, U.S. The final surrender was made at Fort

Bulford, U.S., on the 21st of July, 1S81, in the presence of Inspector

Macdonell, who had been sent on in advance of the Indians by the

Commissioner to inform the United States authorities.

In his annual report

for 1881, Lieut.-Colonel Irvine, Commissioner of the Mounted Police

wrote:

"I cannot refrain from

placing on record my appreciation of the services rendered by

Superintendent Crozier, who was in command at Wood Mountain during the

past winter. I also wish to bring to the favourable notice of the

Dominion Government the loyal and good service rendered by Mr. Legarrie,

trader, who at all times used his personal influence with the Sioux in a

manner calculated to further the policy of the Government, his

disinterested and honourable course being decidedly marked, more

particularly when compared with that of other traders and individuals.

At the final surrender of the Sioux, Mr. Legarrie must have been put to

considerable personal expense, judging from the amount of food and other

aid supplied by him." |