|

THE SARCEES.

THE Sarcees are a

branch of the Beaver or Castor tribe of Indians of the great Athapascan

stock, which extends over the north of British America in scattered

bands, through Oregon and California into Northern Mexico, and includes

the Umpquas, Apaches, and other tribes. At some period beyond the

recollection of the oldest members of the Sarcee tribe, it came under

the protection of the Blackfoot Confederacy, and was united with it. The

Beaver Indians still live in the district of Athabasca, where are found

the Chippewayan, Slave, Dog Rib, and other Indian tribes.

Only in the traditions

of the people can we learn anything of this strange isolation of the

Sarcees from their kindred in the far northern country. Tradition says

that in the distant past a young Beaver chief shot his arrow through a

dog of one of his fellow braves, who was deeply enraged, and vowed

vengeance. His friends rallied to his assistance,, and eighty men fell

dead as the result of the quarrel. Great was the sorrow in the camp, and

a temporary truce was arranged, but sixty people who were friends of the

chief who had killed the dog agreed to separate from the tribe and seek

a home in another part of the land. They journeyed southward by the

shores of the Lesser Slave Lake until they reached the plains and

valleys of the Great Saskatchewan.

More than a century

passed by, and no tidings were ever received from this exiled band. A

young Beaver Indian accompanied a white fur hunter southward, and on

their journey they camped at one of the forts in the valley of the

Saskatchewan, where strange Indians were seen loitering about the

palisades. They were members of the great Blackfoot Confederacy. Among

them were some braves who spoke a language different from the Blackfoot

tongue, and as the Beaver Indian listened he recognized his own

language, for in these men he found the descendants of the long lost

band of the Beaver tribe. These are the Sarcee Indians of the present

day.

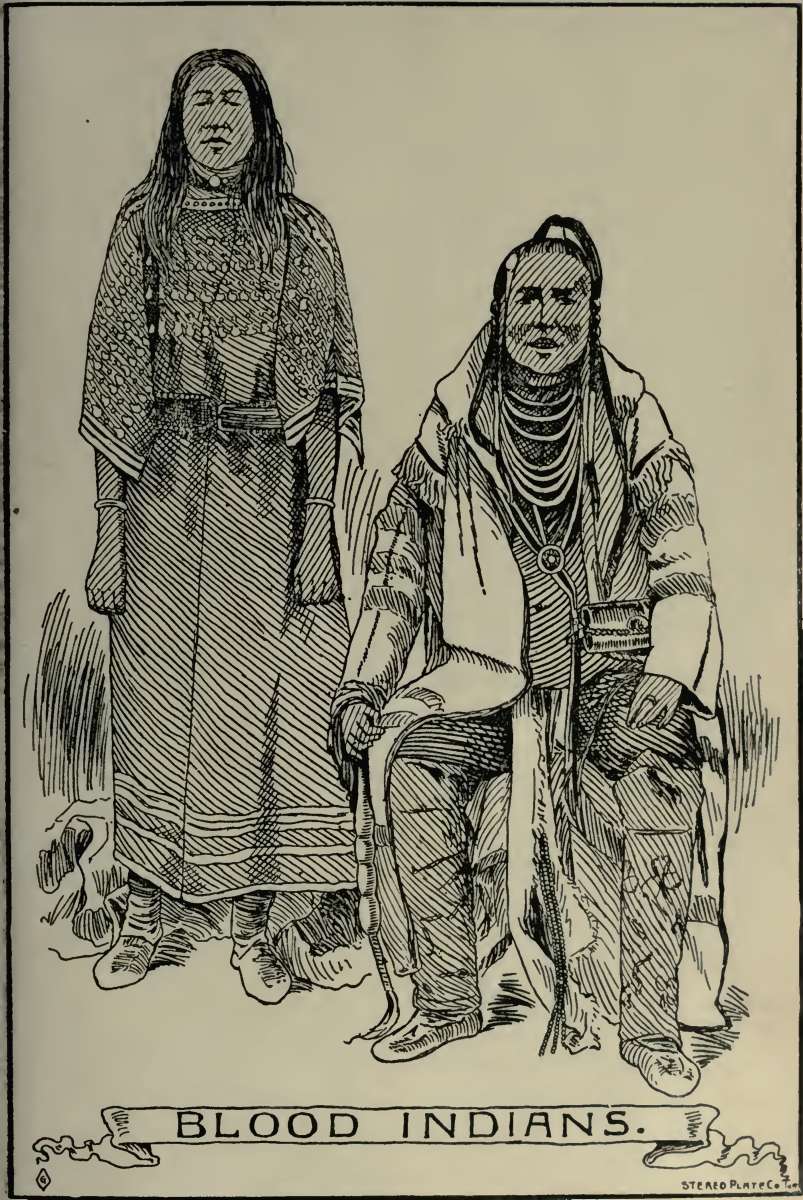

In the summer of 1880,

when the writer reached Fort Macleod, he found the Sarcee Indians camped

upon the Old Man's River, along with some Blackfoot and Blood Indians,

where they were being supplied with rations by the Government—the

buffalo having left the plains and gone south to the plains and valleys

of the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers. The majority of the Bloods and

Blackfeet were in Montana hunting the buffalo, and did not return till

late in the fall of that year. Some of the Sarcee children attended the

day school taught in Macleod by my wife, along with Bloods, Blackfeet

and half-breed children. It was then estimated that the Sarcees numbered

about seven hundred, although the Government agent thought that there

were not more than three or four hundred.

Sir John Franklin's

estimate in 1820 was that there were one hundred and fifty lodges, with

an average of eight persons to each lodge, or a total of twelve hundred

persons. Rowand, an old trader, in 1848 counted forty-five lodges, or

three hundred and fifty persons. Sir George Simpson reckoned fifty

lodges and three hundred and fifty persons in the year 1841. An old

friend of the writer, who has lived for fifty years in the country, told

him that during the year of the small-pox he had counted at the Marias'

River not less than one hundred "dead lodges," in which there was an

average of ten bodies. It is, therefore, difficult to make a correct

estimate of this tribe with such conflicting testimony, but there is no

doubt that the population must have been quite numerous, lessened at

times through the depopulating ravages of war. They were said to be "the

oldest of all the tribes that inhabit the plains," and those who have

come in contact with them in these later years can add to this

testimony, that they are the most saucy, independent and impudent tribe

of Indians that dwell in Northwestern Canada. They have ever been

friends and allies of the Blackfeet, and enemies of the Crees. At times

they have protected solitary Crees against the evil intentions of the

Piegans and Blackfeet.

The Sarcees are of

medium height, very few tall men being among them: the women,

especially, being small. During the old buffalo days they exhibited

their pride in beautiful dresses and fine buffalo-skin lodges, but the

departure of the buffalo reduced them to poverty, the lodges were used

for moccasins, and many of their horses were sold to obtain food and

clothing. The traders and the "old timers" in the country were ever

suspicious of these people, believing them to be deceitful, and

consequently were ever on their guard against treachery. Like the other

plain tribes, they were good hunters, delighting in hunting the buffalo,

and when they had secured an abundance of food, spent their days and

nights feasting and gambling.

Alexander Henry's

journal says of the people: "The Sarcees are a distinct nation, and have

an entirely different language from any other nation of the plains, and

very difficult to acquire from the many guttural sounds it contains.

Their land was formerly on the north side of the Saskatchewan, but they

have now removed to the south side, and dwell commonly on the southward

of the Beaver Hills, near the Slave Indians (Blackfoot Confederacy),

with whom they are at peace. They have the name of being a brave and

warlike people, whom the neighboring nations always appear desirous of

being on amicable terms with. Their customs and manners seem to be

nearly the same as the Crees, and their dress is the same. Their

language bears a great resemblance to that of the Chippewayans; many

words are exactly the same, from which their apparent emigration from

the northward gives every cause to suppose them of that nation. They

affect to despise the Slave Indians for their brutish and dastardly

manners, and although comparatively few in number, frequently set them

at defiance. They form ninety tents, containing about one hundred and

fifty men bearing arms."

According to Henry's

estimate there would be more than seven hundred Sarcees in the years

1801-1806. In the year 1877 these Indians were included in Treaty number

seven, which embraced Blackfeet, Bloods, Piegans, Stoneys and Sarcees,

which was arranged by Lieutenant-Governor Laird and Lieut.-Col. J. F.

Macleod, at the Blackfeet Crossing of Bow River. The Blackfeet, Bloods

and Sarcees were allowed a Reservation along the north and south sides

of the Bow and South Saskatchewan rivers, part of which was for ten

years only, and the rest in perpetuity. Annuities of money and

ammunition were agreed upon, clothing for the chiefs once in three

years, a certain number of cattle and farming implements were to be

supplied, and teachers sent to teach their children. The head chief of

the Sarcees, Bull's Head, on behalf of his tribe, signed the treaty.

The Blackfeet settled

gradually upon their Reserve, but the Bloods and Sarcees became

dissatisfied and would not locate at Blackfoot Crossing. Finally the

Bloods located on a Reservation which was allotted them on Belly River,

south of Macleod. A few months after our arrival at Macleod the Sarcees

were sent to Blackfoot Crossing under the charge of "Piscan" Munro, but

they remained dissatisfied, as they alleged that the Blackfeet were

domineering and looked upon them as intruders. They were removed to Fish

Creek Indian Farm, where they remained for about a year, and at last

they were located on their present Reservation, about eight miles south

of Calgary. In 1889 the Sarcee population numbered three hundred and

thirty-six, and the outlook is dark indeed, pointing toward their

extinction, although the Government is aiding them materially, striving

by means of agent, farm instructor, and rations to train them to become

self-supporting.

Their language is a

very deep guttural, the sounds emanating from the throat, which renders

it difficult for a white man to understand or learn. The writer has

known several persons who have attempted to learn it, not one of them

having been able to acquire the power to speak it with precision. The

people speak their own language amongst themselves, but in conversation

with others use the Cree or Blackfoot languages. Owing to their

relationship to the Blackfoot Confederacy, and their proximity to the

members of it, they use the Blackfoot language more than the Cree, and

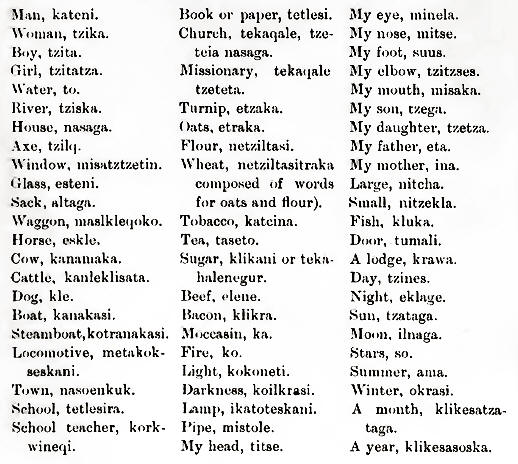

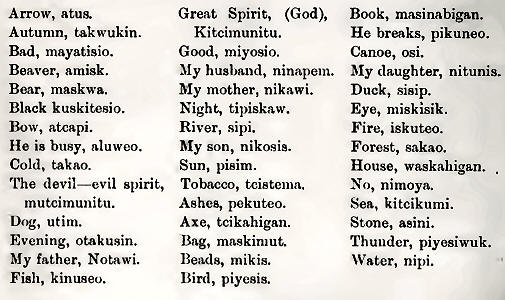

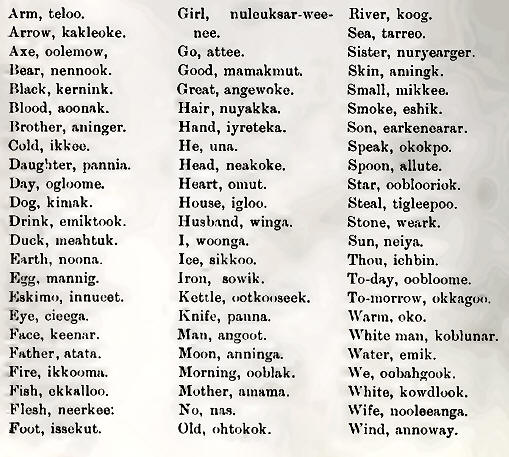

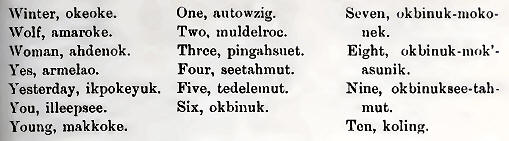

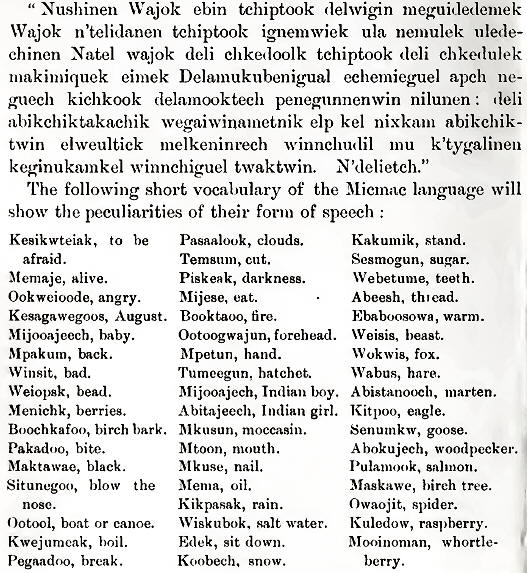

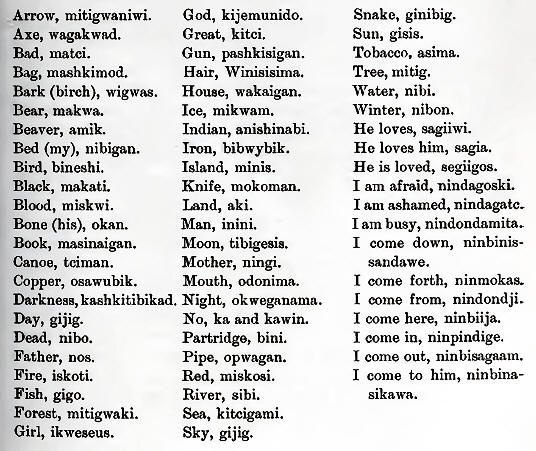

seem to be perfectly at home when using it. The following vocabulary,

gathered from the Sarcees, will give a slight idea of the language :

Mackenzie, in his

"Voyages," says: "The Sarcees, who are but few in number, appear from

their language to come, on the contrary, from the north-westward, and

are of the same people as the Rocky Mountain Indians, . . . who are a

tribe of the Chippewayans."

In Bancroft's "Native

Races" we learn that Umfreville, who visited these people, compares

their language to the cackling of hens, and says that it is very

difficult for their neighbors to learn it; that Richardson compares some

of the sounds to the Hottentot cluck; and Isbister calls them " harsh

and guttural, difficult of enunciation, and unpleasant to the ear."

Horatio Hale, in his

"Ethnology in the United States Exploring Expedition," says the Sarcees

speak a dialect of the Chippewayan (Athapascan) allied to the Tahkali;

and Latham classes the Beaver language as transitional to the Slave and

Chippewayan proper. Mr. Howse, who spent several years in the northern

country, and published a grammar of the Cree language, says of the

Indian tongue: "As the Indian languages are numerous, so do they greatly

vary in their effect upon the ear. We have the rapid Cootoonay of the

Rocky Mountains and the stately Blackfoot of the plains, the slow,

embarrassed Flathead of the Mountains; the smooth-toned Pierced-nosed,

the difficult Sussee (Sarcee) and Chippewayan; the sing-song Assiniboine

the deliberate Cree, and the sonorous, majestic, Chippeway. The writer

can corroborate these statements from his association with the tribes

mentioned. Oftentimes has he tried to understand the Sarcee tongue, as

he has conversed with the natives in the Blackfoot tongue, but the

clicking sound of many of their words and the double

guttural made it

impossible. The whole of their language seems to consist of clicks and

gutturals, that it is difficult to distinguish one syllable from

another, and the study of the language had to be given up in despair.

The women and children invariably speak the Sarcee language, but the men

use in addition the Blackfoot and Cree.

The writer does not

know of any literature in the Sarcee language, but in the parent Beaver

and Chippewayan tongues there exists quite an extensive list of

vocabularies and religious works; most of them, however, are small. In

the Chippewayan tongue there have been translated the New Testament, the

Ten Commandments, hymns, prayers and catechisms. Translations of legends

and songs of the people have been made. Small grammatic treatises and a

syllabary, tribal names, and vocabularies have been also arranged.

Missionaries, traders and travellers have done considerable work in the

language of the Chippewayans. The Beaver language has some translations

of the same character, though not so numerous. The Sarcees have, in a

great measure, been overshadowed by the tribes in their vicinity, and

less attention has been paid to them by travellers and missionaries than

to their kindred in the far North, and consequently they have no printed

works in their language.

They are similar in

their political and social organization to the Blackfeet, having a head

chief over the tribe and a minor chief over each band. They have also an

annual sun dance, which cannot be of Athapascan origin, but must have

been learned from the Blackfeet. Indeed, in all their social customs,

they are essentially members of the Blackfoot Confederacy. They are sun

worshippers, whose religious ideas have been modified through contact

with the white people. Dancing and singing, and throwing the wheel and

arrows are native amusements, to which they have added card playing,

which they have learned from the white people.

The boys run naked in

early childhood, having occasionally a garment or cloth around their

loins. The girls are always dressed, although the raiment is oftentimes

scanty. At the early age of twelve or thirteen the girls are sold in

marriage; sometimes to an old man, who may have several wives. Polygamy

is practised amongst them, although not to so great a degree as in times

of war, when the men were slain and the women compelled to marry members

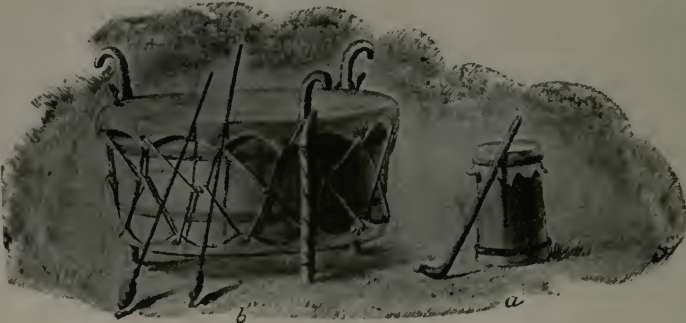

of their own tribe. In the long winter evenings they will gather in

their lodges, or in their modern log houses, and, with drum and song,

have a tea dance, where tea is drunk in profusion and the well-filled

pipe is passed around. Stories of the old buffalo days are told, wherein

the narrator has been one of the principal actors, and as the aged man

tells vividly of battles, scalps, hairbreadth escapes, horses, and women

captured, and glorious wounds, the hearts of the young men are thrilled,

and they long for the time when they may follow in the footsteps of

their forefathers; but when they step beyond the lodge they see the

agent's house, and they are at once confronted with the fact that the

pale-face dwells in the land, and he has come to rule. Thoughts too deep

for words rankle in their breasts, and fain would they live a hunter's

life and taste the sweets of war. Brought into contact with civilization

their native customs are dying out.

The Government is

seeking to teach them agriculture, which is a difficult thing to do, as

they are by nature hunters. Yet they are progressing slowly, as can be

seen by the fields of grain and roots which they cultivate upon their

Reservation. The children attend the Government school, and an English

Church missionary ministers unto them in spiritual things. The influence

of the sun dance is passing away, and the war instinct is being

suppressed through their inability to contend with their enemies. Their

close proximity to Calgary is injurious to the morals of the white

people and Indians, as the natives of the plains always find the lower

stratum of society ready to teach the willing learner lessons of

immorality, and degradation is sure to follow any close relationship of

Indians with white people in the early stages of their training. Because

of this expression of immorality and a longing on the part of some

people for their fine tract of land, there has arisen an agitation for

the removal of the Sarcees, but as the Canadians have ever been lovers

of fair play, the better class of people will not listen to any question

of removal except upon conditions agreeable to the treaty and British

law.

The outlook for these

Indians is not very bright, yet we are unable to predict their ultimate

condition, as they are still in a, transition state. The sudden

appearance of a contagious^ disease would sweep them off the face of the

earth, while care may preserve them as a remnant of a powerful tribe,

transformed through stages of civilization from a bold, independent and

war-like race, into a thriftless number of serfs, without ambition or

manhood. Education, training in the arts of peace, and the Gospel may do

much to enlighten and inspire them with an earnest desire to attain a

position of respectability, and this is the hope of those who have the

welfare of the Sarcees at heart. They are well cared for, but they feel

keenly their changed condition, which is seen in their tawdry dress and

habits of uncleanliness, and without hope they cannot succeed. A pang of

sorrow comes to the heart in contrasting the former and latter

conditions of this tribe. Let us hope for<v .a solution of the Indian

problem in its relation to the Sarcees.

THE STONEY INDIANS

The Stoney Indians are

a branch of the great Dakota or Siouan Confederacy. They are

Assiniboines, of which Stoney is the English translation. According to

Dr. Riggs, who spent forty years among the Sioux Indians, Assiniboine

means Stone Sioux, and is a compound of French and Ojibway. "Bwan" is

the name given by the Ojibways to the Sioux; "assin" is the Ojibway for

a stone. Baraga and other authorities on the Ojibway and Sioux give this

translation of Assiniboine. The derivation of the name is said to come

from the fact that the Assiniboines -cooked their food on heated stones,

and from this custom they received this name, which was translated by

the white people into the Stone People, and finally into Stoney Indians.

We often meet with the names, Stone People and Stone Indians, in the old

books treating of the history of North-western Canada. We have therefore

some branches of the tribe called Assiniboines, and others Stoney

Indians. The Blackfeet call the Stoneys, Suqseoisokituki, which,

however, is not a Blackfoot word. Suqseo must be a Sarcee word, and is

the name given by the Blackfeet to the Sarcees. The full word would

therefore be a combination of Sarcee and Blackfoot, and the meaning in

full is Sarcee-Sioux, the latter part of the word referring to the

Sioux, who are called by the Blackfoots, "Cut-throats." In the Cree

language, Asini means a stone, and Asinipwat a Stone Indian. The

adjective "Stoney" is Asoniweo, and Asinipwatiwio means he is a Stone

Indian. Here we see the relation of the Ojibway to the Cree, both

languages belonging to the Algonquin stock of languages. In David

Thompson's field book of his " Explorations in the North-West," there is

mentioned one of the trading-posts belonging to the North-West Company,

called Upper House on Stone Indian River, which is now named the

Assiniboine. The Sioux were called by the Ojibways, Nado-wessi.

As early as 1660, the

Assiniboines were living in the vicinity of Grand Portage, beyond the

north-west shore of Lake Superior. They were at that time called Poualak,

or Assinipoualacs, and were dreaded by the Upper Algonquins as a warlike

band of Indians, who lived in skin lodges and made fire of coal, as wood

was scarce in the prairie region where they dwelt. In the early maps of

that period, a lake intended for Nepigon is called 'Assiniboines." In

1679 Du Lhut held a conference with the Assiniboines at Kaministiquia,

the site of Fort William of the old North-West Company.f In large

numbers they roamed all over Manitoba and that portion of the North-West

Territory now known as the southern parts of Assiniboia and Alberta.

Alexander Henry, in his "Journal of Adventures," in 1809 gives

the location of the

Assiniboines as follows: "The Assiniboines are from the Sioux. Their

lands may be said to commence at the Hair Hills (Pembina Mountains) near

the Red River, then runing in a western direction along the Assiniboine

River, and from that to the junction of the north and south branches of

the Saskatchewine, and up the former branch as far as Fort Vermilion,

then due south to the Battle River, and then southeast until it strikes

upon the Missouris, and down that river until near the Mandan villages,

then a north-east course until it reached the Hair Hills. All this space

of open meadow country may be called the lands of the Assiniboines. A

few tents of straggling trees occasionally intermixed among them."

The territory of the

Assiniboines became circumscribed by the advent of white settlers, so

that no longer did they roam over this large extent of country, and

finally the Government made treaties with the Indians by which they were

located upon Reserves. They are still widely scattered upon Reserves,

having been assigned to agencies with other Indian tribes, though with

separate Reserves, in the sections of country sometimes selected by

themselves, near where they had made their homes at the time they made

the treaty with the Government. This explains their separation as bands

of Assiniboines and Stoneys in different parts of the North-West,

instead of being located as a united tribe on one Reservation. They are

found at the present time as separated bands of this tribe at Moose

Mountain and Indian Head, in Assiniboia; Eagle Hills, Lac Ste. Anne,

White Whale Lake, and Morleyville, in Alberta. During the early and

middle parts of the present century the tribe was known as Strongwood or

Wood Assiniboines, and Plain Assiniboines, which distinctions have been

changed into Assiniboines, a term applied to those dwelling on the

Reserves in Assiniboia, Mountain Stoneys at Morley ville, and Wood

Stoneys in Northern Alberta. A considerable number of Assiniboines are

resident in the United States.

In the beginning of the

present century, Henry estimated about two thousand fighting men in all

the Assiniboine camps, which would make the total population number at

least ten

thousand people. A

naturalist, named Cuthbertson, travelling for the Smithsonian

Institution, in 1850 gives the probable number of the Assiniboines in

the Upper Missouri and its tributaries as four thousand eight hundred.

Mr. Harriet, an old trader, who had spent his life among the Blackfeet,

stated that there were, in 1842, eighty lodges of Strongwood

Assiniboines, equal to six hundred and forty persons, and Mr. Rowand,

for the same date, gave for the Plain Assiniboines three hundred lodges,

equal to two thousand four hundred, or a total population of

Assiniboines in North-western Canada of three thousand and forty

persons. Mr. Lefroy estimated them, at the same time, as three thousand

six hundred, and Mr. Shaw, at four thousand persons. These men had

travelled in the country and knew a great deal about the Indians. The

change in the population is due no doubt to the fact that their estimate

had reference to the Saskatchewan country, which is borne out by the

fact that Sir George Simpson, in his " Overland Journey," gave for the

Assiniboines in the Saskatchewan district in 1841 four thousand and

sixty persons. The entire population of Stoney and Assiniboine Indians

for the year 1890 in North-western Canada, as given in the Dominion Blue

Book, is one thousand three hundred and forty-two. The cause of this

decrease arises principally from two causes, tribal wars and the plague

of small-pox, which swept them away in large numbers.

Traces of the residence

of these people in Manitoba in the early-part of the present century are

found in the fact that Alexander Henry states that, when returning from

a visit to the Mandans and other Tribes on the Upper Missouri River in

1806, he came to the Tete-de-Beuf region, where there was a hill,

recognised by some at the present day as Calf Mountain, upon the top of

which, the Assiniboines and Crees made sacrifices of tobacco and other

trifles, and collected a certain number of bulls' heads, which they

daubed over with red earth, depositing them on the summit, with the nose

always pointing toward the east.

Instead of continually

using the terms, Stoney and Assiniboine the writer will employ the

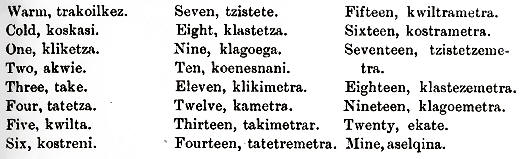

former name as applicable to all the people. The Stoney Indians are of

medium height, a few of the men being of massive proportions, but the

average being rather below medium stature. They are well-formed, of

pleasing countenance and, the Mountain Stoneys especially, active in

their movements and fleet of foot. It is not too much to say that they

are the most energetic of all the tribes of the North-West, well

disciplined, inured to the hardships of prairie and mountain, and of

industrious habits. They are comely in their dress, which has changed

through advancing civilization: the painted faces, hair besprinkled with

red earth and twisted into a sugar-loaf bunch on the top of the head

having been discarded. The native costume of well-tanned deer-skin,

beautifully ornamented by the women, was changed into garments made from

blankets, but many of them are now dressed in modern apparel. The

Mountain Stoneys cut their hair, and their light copper-colored

complexion is attractive. In former years the men wore a profusion of

dress ornaments, like all the other Indian tribes, consisting of rings

on each finger, ear-rings and necklaces, coat and leggings, with colored

porcupine quill or head ornamentation, and their war accoutrements, with

figures wrought or painted upon them. They were very particular about

dressing their hair, especially the young wen. They are none the less

careful about their dress, and more cleanly in their habits at the

present time, but they are more plain in their style, and not so anxious

for display.

The women are small,

but active, neat in their dress and cleanly in their habits. Their dress

is similar to that of the women of the other tribes, although many of

them are imitating their pale-faced sisters. Some of the bands are not

far removed from their old-time modes of dress and habits, but those who

have been brought under the influence of the missionary have advanced

rapidly, and are now models of neatness and activity to the other

tribes.

Before the advent of

civilization, they dwelt in tents made from the hides of the buffalo,

upon the sides of which hung the scalp-locks which they had taken in

war, and around each tent were painted figures, representing the famous

deeds of the master of the lodge. They were famous hunters of the

buffalo, and those dwelling near the mountains and in the woods, pursued

the deer, goat, sheep, and bear, followed the moose, or fished in the

lakes. The babes were snugly shrouded in their moss-bags, and carried on

the back of the mother, whether walking on the prairie or riding upon a

horse. In many of their customs the Stoney Indians were similar to the

Crees and Blackfeet. Their food consisted of buffalo meat principally,

in the winter, and deer, except those in the North who lived on fish. In

the summer they partook of wild roots and berries. They were excellent

horsemen, and had the reputation of being great horse thieves. Their

utensils of the lodge were made principally of wood. The women were very

unchaste, induced by their customs of marriage. Polygamy was practised

among them, and women were bartered for trifles.

The men were inveterate

smokers (a habit in which the women also indulged), and they exhibited

their skill in the manufacture of beautiful pipes. Of their ability in

this direction Sir Daniel Wilson says: " Among the Assiniboine Indians a

material is used in pipe manufacture altogether peculiar to them. It is

a fine marble, much too hard to admit of minute carving, but taking a

high polish. This is cut into pipes of graceful form, and made so

extremely thin as to be nearly transparent, so that when lighted the

glowing tobacco shines through, and presents a singular appearance when

in use at night or in a dark lodge. Another favorite material employed

by the Assiniboine Indians is a coarse species of jasper, also too hard

to admit of elaborate ornamentation. This also is cut into various

simple, but tasteful designs, executed chiefly by the slow and laborious

process of rubbing it down with other stones. The choice of the material

for fashioning the favorite pipe is by no means invariably guided by the

facilities which the location of the tribe affords. A suitable stone for

such a purpose will be picked up and carried hundreds of miles. Mr. Kane

informs me that in coming down the Athabasca River, when drawing near

its source in the Rocky Mountains, he observed his Assiniboine guides

select the favorite blueish jasper from among the water-worn stones in

the bed of the river to carry home for the purpose of pipe manufacture,

although they were then fully five hundred miles from their lodges. Such

a traditional adherence to a choice of material peculiar to a remote

source may frequently prove of considerable value as a clue to former

migrations of the tribe."

Some years ago the

writer saw, at Morley, some beautiful specimens of sculpture, executed

with a pocket-knife by a Stoney boy: among them a moose, buffalo and

dog. They were remarkable exhibitions of native skill, as perfect in

detail as any ever seen. The accurate measurements of the horns of the

moose, and the attitude of the animal in the act of leaping, were

astonishing, considering the age of the sculptor, a youth of not more

than twelve years, his lack of training, and the tools with which he

wrought. His work attracted considerable notice from travellers, and

Senator Hardisty offered to educate the youth at his own expense, but

the offer was refused by the boy's father, who preferred the money

obtained from the sale of the articles to the advancement of his son.

In the early days the

dead were buried in a sitting posture, with the face toward the East,

but now they follow the custom of their white brethren. The people

believed in the transmigration of souls. Charles N. Bell, in his Notes

on Henry's "Journal," states that they believed that sometimes after

death the spirit goes to a river, which has to be crossed on the way to

the happy hunting grounds, where it is met by a fierce red buffalo bull,

who drives it back and compels it to re-enter the body.

The Stoneys have

several games similar to the Blackfeet, including the hoop and arrow

game and the "odd-and-even" game, which is played with small sticks or

goose-quills.

The tribe has its own

system of government, consisting of chiefs and councillors, who compose

their council, at which all questions affecting the welfare of the

people are discussed and settled. They made the laws by which they are

governed, and through the wise administration of the chiefs and council

peace is maintained in the camp. In common with other Indian tribes,

they have a system of telegraphy, consisting of signals by means of fire

at night, and in the day certain movements of their blankets, different

motions of men on horseback, such as riding backward or forward, riding

in a circle, or the rider sitting with his back toward the horse's head.

By the use of a looking-glass they are able to communicate with each

other at a distance of three or four miles. The writer was in the Stoney

camp on a Sunday, conducting service, when an Indian was seen riding at

a distance of two or three miles. One of the chiefs stepped aside, drew

forth his looking-glass, which is carried by every Indian, and holding

it so that the sun would shine upon it, sent a flash toward the rider.

The Indian stopped upon his course, waited a moment or two, as the chief

sent his message to him, and then rode toward us. This tribe had many

famous warriors, and so great was the prowess of the people that, though

less in number than the Crees or Blackfeet, these tribes were afraid of

them. They were brave and skilful in the use of the bow and arrow, and

no less expert in later years with the rifle. Famous as scouts, they

were employed during the Riel Rebellion of 1885 in that capacity, and

faithful were they in the performance of their work. Alike were they

noted as hunters on the plains in the days of the buffalo, and in the

mountains, spending the greater part of the year in the pursuit of game.

The old-time custom of

naming their children from some physical characteristic or peculiar

circumstance at the time of birth, and changing them at different

periods in life, as expressive of some great deed or mean action, has

passed away in a great measure, and many of them, through the

missionary's influence, have adopted Christian names. Contact with white

people and religious influence has caused many of them to reject the old

tent-life of the camps, and erect good log-houses, with many of the

conveniences of modern civilization. They still retain their love for

dogs, although they are not used as beasts of burden to any extent,

which was a custom of the old times. The mountain Stoneys have acted as

guides to hunting parties, and during the explorations for the route of

the Canadian Pacific railroad, many of them were employed, rendering

excellent service. During the construction of the railroad they got out

of the woods large quantities of ties.

The native religion,

with its belief and ceremonies, has disappeared. Their traditions

consisted of an admixture of the Sioux and Cree traditions, caused by

their relation to the former and contact with the latter tribe.

The}- have, in common

with the other Indian tribes, a sign language. The spoken language is a

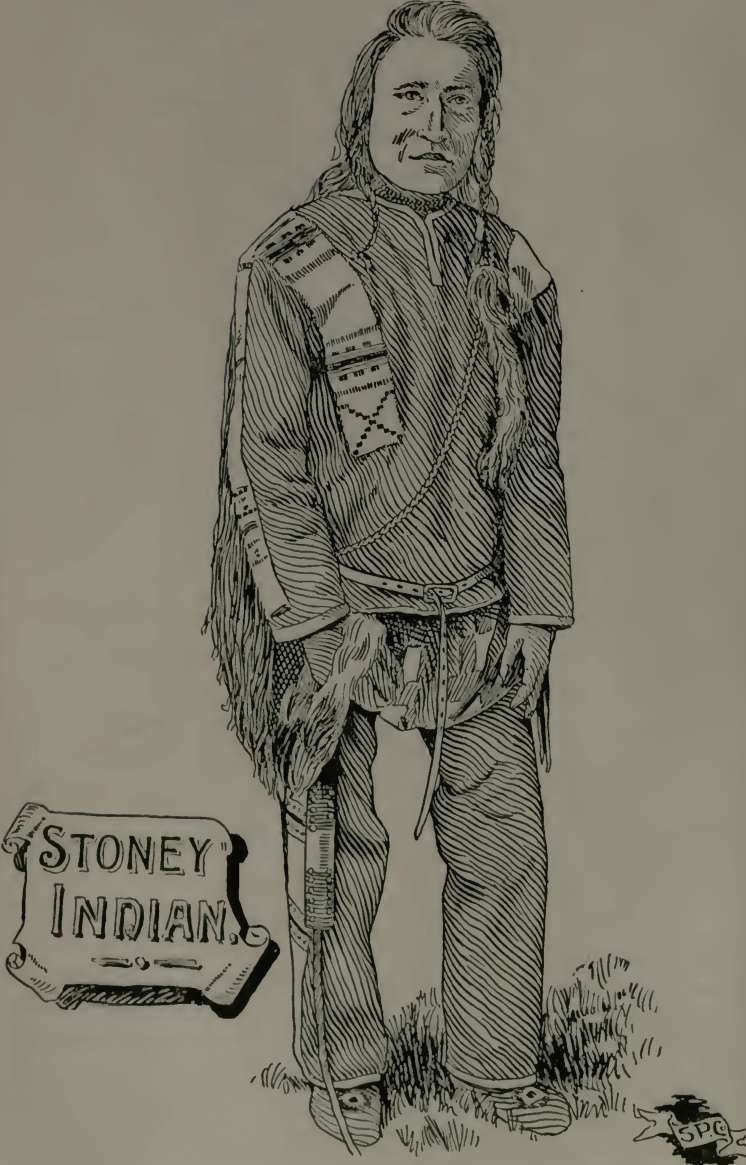

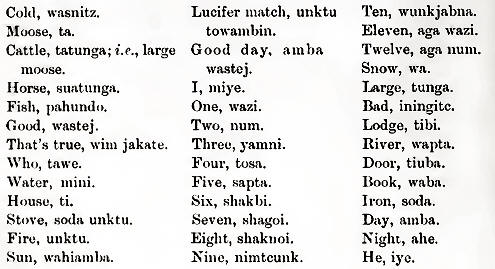

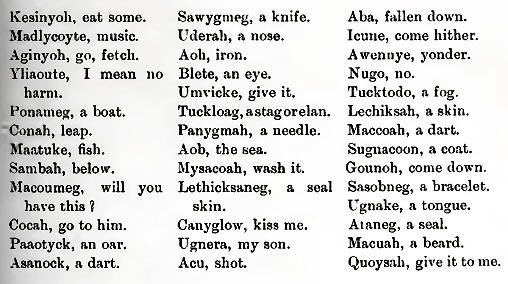

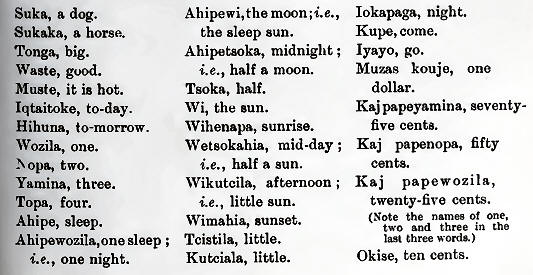

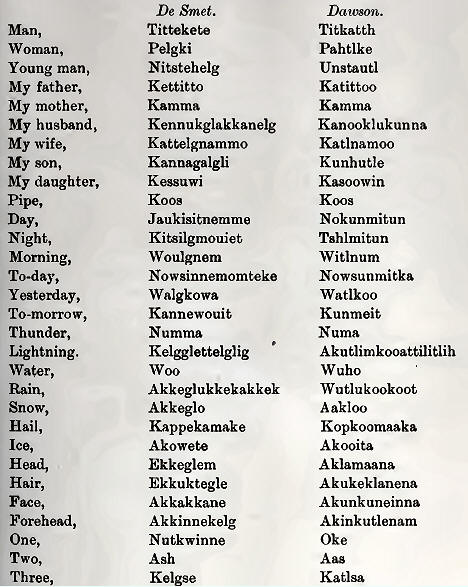

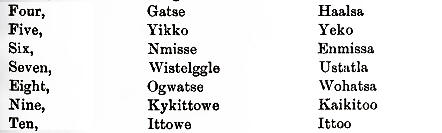

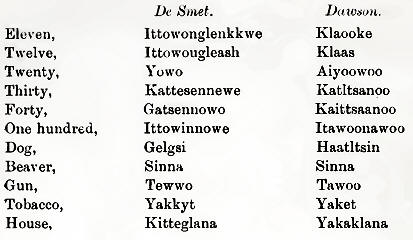

dialect of the Siouan language, which the following words, collected

among the Stoneys, will give the reader a slight idea of its

construction and significance:

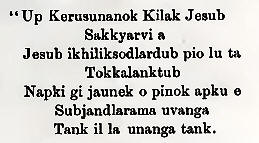

The literature of the

Stoney Indians is very meagre, owing, no doubt, to the fact that they

are able to read the books printed in the Syllabic characters of the

Cree language. A few vocabularies have been printed in books treating of

the Hudson's Bay country and the fur trade, some personal names, the

numerals, and the Lord's Prayer.

The Jesuit missionaries

were the first religious teachers who came in contact with these people,

and they remained alone in the field, meeting them occasionally as these

nomads of the plains visited the missions. In 1840, the Rev. Robert

Terrill Rundle, Methodist missionary, went to the North-West ami began

operations among the Indian tribes of the Saskatchewan. Frequently he

conversed with the Stoneys at Fort Edmonton, and accompanied them in

their hunting expeditions, teaching and preaching. He enjoyed some

measure of success, the people learned to sing hymns in the Cree

language, and were instructed in the truths of the Christian religion.

After laboring eight years in the Saskatchewan, at Edmonton, Pigeon

Lake, and on the plains, he was compelled to return to England, because

of injury received through a fall from his horse. His brother-in-law,

the Rev. Thomas Woolsey, succeeded him in this work among the Crees,

Stoneys and Blackfeet, and through the labors of these devoted men, a

band of faithful local preachers was raised, who preached to the people

as they travelled upon the plains or roamed through the mountains in

search of food. The hymns taught the people in these early years are

still remembered, but the tunes have undergone a change, a peculiar

Indian turn having been given to them, so that they have become

essentially Indian tunes, founded upon their English predecessors.

In 1885, Rev. Thomas

Woolsey wrote: "Many of the Cree and Stone Indians were members of our

Church in 1864." Woolsey was stationed at Edmonton the year previous

when Rev. George McDougall and his family arrived at Victoria from

Norway House. The Mountain Stoneys were sought out, and the work of

evangelization continued among them. A fuller account of the doings of

these men can be found in the works of the writer, "The Hero of the

Saskatchewan," "The Indians of Canada," and "James Evans." The mission

among the Mountain Stoneys at Morley was begun in the autumn of 1873, by

Rev. John McDougall, who still remains at his post. Visitors to Morley

cannot fail to be deeply impressed with the attitude of reverence

manifested by the people as they assemble for service in hundreds,

filling the commodious church, drawn together by the sound of the bell,

whose peals are heard far down the beautiful valley of the Bow River.

The singing is hearty, the attention given to the preacher, who may be

the missionary himself or one of the native local preachers, is deep,

and the whole service is so earnest, reverential and true that the pale

face receives impressions which he can never forget. There is an

orphanage at the Mission, two good schools upon the Reserve, and a

faithful band of men and women striving to lead these people to imitate

the life of the Man of Nazareth.

Deep was the sorrow of

these people at the loss of Rev. George McDougall, who was frozen to

death a few miles north of Calgary. When the writer lived at Macleod,

some Stoney Indian women visited the mission-house, and during the

conversation they drew from under their blankets the Bible in the Evan's

Cree Syllabic characters, with their Methodist class tickets. During a

tour of visitation in the Porcupine Hills, the writer met a Stoney

Indian who recognized him, and together they called at a friend's house

for a night's shelter. When shown the place where he was to sleep, an

adjoining building to the house, which was not very clean, he turned to

the rancher and said, as he stood in his native dignity, " I am not a

dog, I am a man."

When the school

teacher's wife died at Morley, the Indians, who had been absent on their

hunting trips, upon their return repaired to the cemetery, as they

looked at the grave, cast small twigs and flowers upon it, saying, with

deep emotion, "She was a good woman. She was a good friend to us."

Shortly after the

rebellion of 1885, Mr. McDougall accompanied three Indian chiefs to

Ontario and Quebec. One of these men was Chief Jonas, of the Mountain

Stoneys. He is reported to have said, among many of the addresses which

he gave to the white people, that he was glad to see so many people

worshipping the Great Spirit, for it strengthened him. At one time he

thought that those who believed in Christ were few, and those who did

not follow Him were numerous, but now he had seen for himself that the

Christian people were a great multitude. He would go back and tell his

people that they were in the right way, for there were multitudes

believing in the same Christ. He would tell .his people of the cities he

had seen and the multitudes praising God. He wished the white people to

help him keep the fire-water out of the country. " At home the railroad

came to us, and I thought that was a wonderful power. But, then, when I

reached the steamboat I found another great wonder to my mind. All that

has been surpassed since I came to the city (Toronto) this evening. I

don't know how to describe the great big buildings and the multitudes of

people, and the lights, which are like lightning. I shall be happy if I

and my people, in even a humble way, will be able in our future to

emulate this progress." Schools have been established among the Stoney

and Assiniboine Indians on all the Reserves and the children are making

good progress in their studies.

Presbyterian, Roman

Catholic and Methodist missions are maintained among the Stoneys in the

Edmonton district, where there is a Reserve on Sandy Lake, about sixteen

miles west of Edmonton. The Government assists the bands, providing farm

instructors and agents to teach them farming and look after their

interests. As they are generally an industrious people, they are

progressing favorably and raise good crops. The women are experts at

knitting gloves and mittens on the Reserve near Indian Head, and find a

ready sale for all they make. Upon the other reserves they are also

industrious. The Mountain Stoneys have some fine bands of cattle, of

which they are legitimately proud. As treaty Indians they have always

been friendly to the white people, a fact noted by Lord Southesk and

other travellers, who have visited their camps or met with them in their

travels. Despite the decrease of the native population, there is hope in

their progress in agricultural and industrial pursuits, and their

independent spirit, that they will ultimately maintain a place among the

white people, as a remnant of a powerful tribe of a great confederacy,

which once roamed the western plains.

THE MOUND-BUILDERS.

Many centuries before

the Pilgrim Fathers landed in New England, or Columbus planted the

standard of the Spanish crown on the soil of the New World, there lived

and perished a race of people on our continent, concerning whom very

little is known. They were men and women of like passions to the

dwellers of the villages of the nineteenth century, possessed of a

worthy civilization, peaceable, affectionate and intensely religious.

Their villages have been destroyed ; nothing of their literature is

known; not a single trace of their language is in existence, and even

the name of this strange people is lost to us. Search the histories of

the nations of the world, and not a kindly pen is found that can tell us

the name of this mysterious people who came to our land, became a large

and prosperous nation, and then passed away, leaving only their cities

of the dead to tell us in voiceless language the story of their life. We

call them Mound-Builders, because of the monuments they have left us—the

stately empire of the spirit king. Humboldt says: "The Mound-Builders

were eminently a water people," and Ignatius Donnelly tells us that they

were wanderers from a large continent that existed in the Atlantic

ocean, called "Atlantis," but many eminent scientists hold theories at

varience with these opinions. Evidence has been adduced by scholars to

show that they crossed the Atlantic and settled in Mexico, and again

others testify to their migration from China and Japan by the Behring

straits. There were men in China who built mounds, as is learned from

the fact that about ten miles from the city of Kalgan there is a cluster

of over forty mounds, one of them being thirty feet high, and four

hundred and twenty feet in circumference at the base, and an oval mound

forty-eight feet in length at the summit. Before Julius Cresar invaded

Britain, the Nahuas entered Mexico, and made their houses there,

becoming a great people. These were followed by the Toltecs, who left

architectural monuments, significant and beautiful. The Mound-Builders

also went to Mexico, and stamped the impress of their existence, but it

is impossible at this distant date and with our present knowledge of

facts to identify them as the Nahuas or Toltecs. The book of Mormon

states that the Indians are the descendants of a Hebrew immigration, and

some writers believe that the Indians are the offspring of the Mound

Builders; and, again, others say that the Mound-Builders are the direct

lineage of the ten lost tribes of Israel. The leanings of evidence are

in favor of the Toltea' relationship, and still we cannot press any

theory, for the path we tread is a hazy labyrinth, and not a single

voice or penis raised that can show us the way. Along the rivers and

lakes they travelled as a peaceful race of nomads, erecting mounds for

observation in time of war; burial mounds, in which to place their dead;

sacrificial mounds; symbolical mounds, for performing the rites and

ceremonies of their native worship; enclosures for defence; and sacred

enclosures for religious purposes. Mounds are found in great abundance

in Ohio, Wisconsin, Indiana, Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi,

Alabama, Georgia, Arizona, New Mexico and Florida. There Are none found

in New England, but westward toward the Rocky Mountains, in the

Yellowstone country and Manitoba, there have been some discovered.

Groups of mounds have been opened at various places in Manitoba,

including the parish of St. Andrew's, near Winnipeg, the Souris river,

Riding Mountain and Rainy River. Over twenty mounds having been

discovered at the last mentioned place.

The centuries have come

and gone since these strange people lived in the land and made the

mounds. Heavy forests have grown around the mounds, hiding them from

view, and destroying their usefulness for observation in times of war;

massive trees have even grown upon the top of them, and along the river

banks, where many of them are seen, the river has cut a new channel and

left the mounds "high and dry" since the last mound was built.

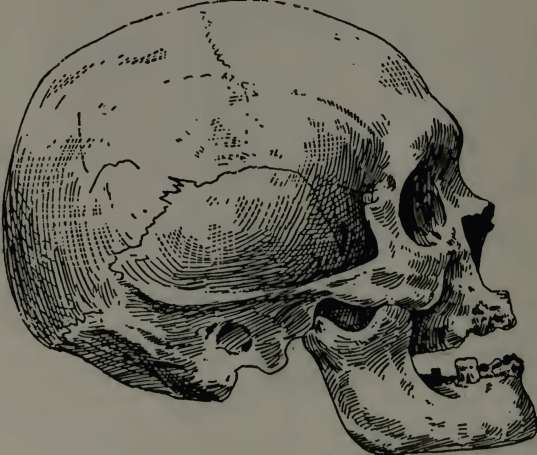

In the burial mounds

have been found stone implements of: peace and war, as arrow-heads,

spear-heads, axes, knives, hatchets, rimmers, spades, chisels, pendants,

gorgets, pipes, shuttles, badges of authority, mauls or hammers,

pestles, tubes, hoes, copper ornaments, bone implements, articles of

pottery and cloth have been taken from them. The skeletons taken from

the mounds of sepulture have been incomplete, owing to their great age.

Very few skulls have been found worthy of preservation.

In an age when there

was no machinery in the land, the work of these people are in many

instances gigantic. There is a notable fortification in Warren County,

Ohio, about thirty-three miles north-east of Cincinatti, called Fort

Ancient. This defensive enclosure has a wall five miles in extent,

encircling an area of one hundred acres. The embankment is built of

tough clay, from five to twenty feet in height, with an average of nine

feet, and containing six hundred and twenty-eight thousand eight hundred

cubic yards of excavation. There are over seventy gateways in the

embankment, from ten to fifteen feet wide, and within the works are

twenty-four reservoirs.

Still more elaborate

and complicated are the Newark works, near Newark, Ohio, consisting of

an extensive series of square, circular and polygonal enclosures, with

mounds, ditches and connecting avenues, extending over about four square

miles.

The great Cahokia

mound, seven miles east of St. Louis, comprises a parallelogram, with

sides measuring seven hundred and five hundred feet, respectively, and

rising to the height of ninety feet. It covers an area of six acres, and

its estimated solid contents amount to twenty million cubic feet. There

is a terrace reached by a graded way, one hundred and sixty by three

hundred feet, and the summit of the pyramid being truncated, made a

platform two hundred by four hundred and fifty feet, upon the top of

which stood a conical mound ten feet high. Dr. Forster has expressed the

probability that upon this platform stood a capacious temple, within

whose walls the hi£h priests performed their mysterious rites at stated

seasons in the year, as the vast multitude in the plain below gazed in

wonder and waited with holy reverence the completion of the religious

ceremonial.

The Grave Creek mound,

near Wheeling, is nearly one thousand feet in circumference at the base,

and seventy feet high.

It was excavated in

1838, and within it were found two sepulchral chambers, containing three

skeletons.

The wonderful temple

mounds are distinguished from the other classes of mounds by regularity

of form, greater size and graded ways leading to the summit. Aroused by

religious sentiments and impulses the Mound-Builders no doubt erected

these mounds as sites for temples, a striking example of which is seen

in the temple mounds at Marietta, Ohio, and there, in answer to the cry

of the soul, sought guidance and peace in sacrifice to their spirit

guides.

There are mounds of

observation placed upon high hills, that signals might be transmitted

from one place to another and a watch kept. One of these observation

mounds is situated at Miamisburg, Ohio, and commands a view of the

valley of the Great Miami.

Symbolical mounds

abound chiefly in Ohio and Wisconsin. The mounds represent foxes,

lizards, buffalo, bear, raccoon, otter, elk and many other kinds of

animals and birds. The most significant of all the symbolical mounds is

the great Serpent Mound in Adams County, Ohio, which is seven hundred

feet long, five feet high and thirty-six feet wide at the centre ; and

the Elephant Mound in Grant County, Wisconsin, which is about one

hundred and thirty-five feet long, thirty-six feet wide and five feet

high. This mound represents an elephant, or ancient mastodon of the

American continent, and the existence of this representation reveals the

fact that the Mound-Builders have seen the animal or they could not have

made this" mound. From the contents of the mounds ethnologists form

their opinions relating to the Mound-Builder as a man. From the

existence of pottery, cloth, arrow-heads, hoes, fishing-spears, sinkers

for sinking the seines, pipes and many other relics, ethnologists would

make the Mound-Builder to be a man of peace, devoted to raising corn and

fishing, possessed of artistic ability, as evidenced by the beautiful

arrow-heads and the ornamented pottery found. The tiny childrens' stone

hatchets and other playthings discovered beside the skeletons, show the

affection of the people for their offspring. Moral and religious in

their life, as manifested by the representations of their deity, the

sun, and the existence of only a single specimen of obscene art in the

thousands discovered, they looked for an immortality and a sensual

heaven, as shown by the relics in the graves.

When the Mound-Builders

were at the height of their power invaders came from the north, as

learned from the situation of the mounds, and harassed these people in

their fortifications and observation mounds, overthrowing them

completely, so that they were compelled to flee to Mexico, where finally

they passed away without leaving any record of their fate. The people of

the northern mounds in Canada may have followed their brethren, as a

remnant of a great nation, or the last of the Mound-Builders may have

lingered on, a stranger among the red men, until he perished without a

grave. It is a sad and voiceless story these mounds have to tell us, of

a people who were dwellers in our land in the days of yore, and we

confess that we have been touched with sympathy and our interest has

deepened as we have followed the story until the end.

THE NEZ PERCE INDIANS.

The Nez Perce Indians

are a tribe belonging to the Sahaptin family, a large and interesting

stock. The tribe is sometimes called the Sahaptin, but the Nez Perces

are one of the branches of this family. They do not derive their name

from the fact that they pierce their noses, but they were so named by

some of the early travellers who classed them along with others of the

Sahaptin family, who pierce their noses. The early travellers and

traders called them Nez Perces, but the Indians called themselves

Chopunnish. They are not strictly a Canadian Indian tribe, as they dwelt

chiefly in the early years in Idaho, Oregon and Washington Territory,

but as they were frequently found upon the boundary, and I have met and

often conversed with a small band of these people, who still make their

home in the Pincher Creek country in the district of Alberta, I thought

a short sketch of this interesting tribe might be acceptable to my

readers.

It was in the summer of

1880 that I met among the foothills of the Rocky Mountains a Umattilla

Indian and some of the Nez Perces, who had crossed the mountains from

the Walla Walla country, and were hunting and trading horses. From the

year 1843, when we first learn anything about these people, through the

official records of the United States Government, and before that

period, as shown by the writings of travellers, they roamed throughout

Idaho, Washington and Oregon, hunting and fishing. Not until after the

outbreak under Chief Joseph did any of them seek a refuge in Canada.

Amongst the numerous

tribes of Oregon they were the noblest, richest and most gentle; a

typical race, noted for strength of body and mind, native prowess,

heroic virtues and gentle manners. They were a powerful tribe, owning

many horses, and esteemed highly as expert horsemen. They were far

removed from the common idea held concerning the red men, as they had

good minds and thought well on all matters affecting their interests as

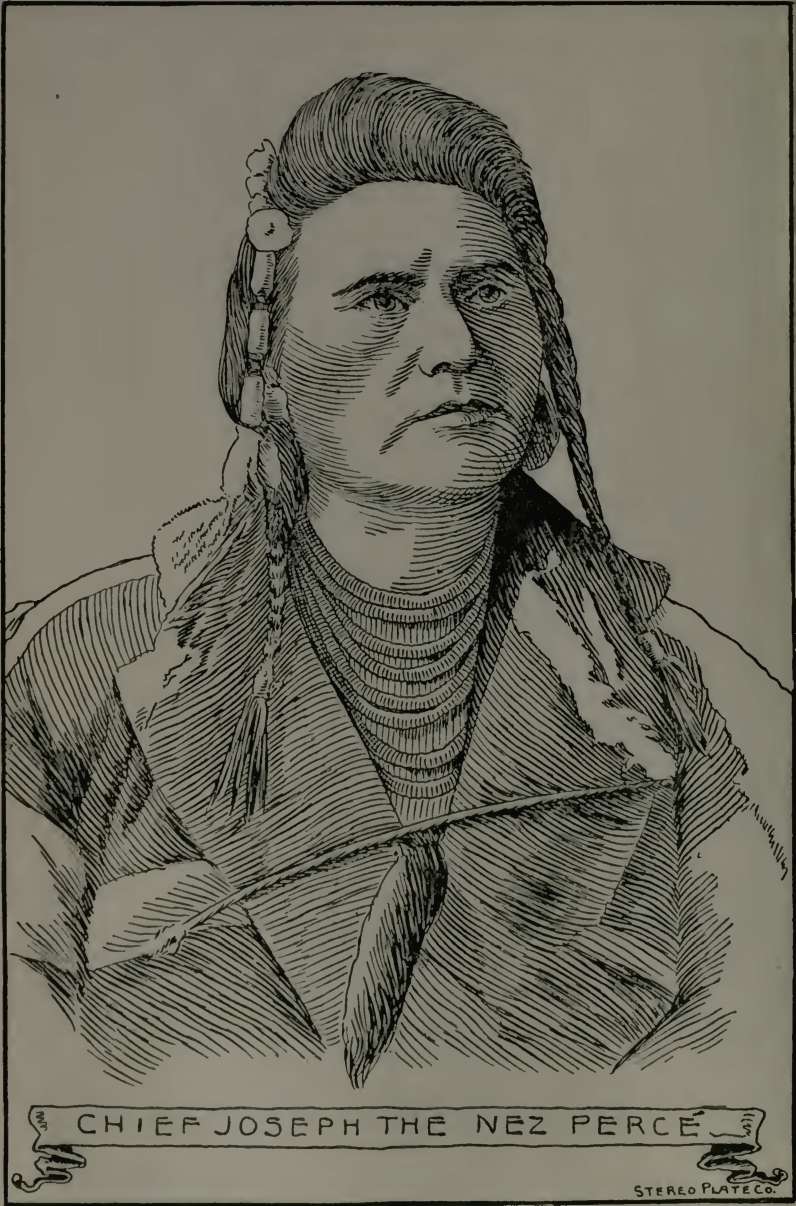

individuals and as a tribe. Chief Joseph, the leader of the Nez Perces,

during their contest with the Government of the United States, has been

described as "the ablest, uneducated chief the world ever saw." When

these people were removed from their home and sent to another

Reservation, as they were being taken down the Missouri river, the

people who lived upon the banks of the river and had been accustomed to

Indians all their lives, remarked: "What fine-looking men!" "How clean

they are!" "How dignified they appear!"

The homes of these

people were similar to that of the other tribes, consisting of lodges,

ornamented according to the taste, dignity and valor of the owners. Life

in the camp was similar to that of adjacent tribes. Dogs were numerous,

and hated the white man; children roamed abroad at their own sweet will,

unencumbered with much clothing, satisfied with nature's provision as to

dress, and happy amid all their wild surroundings. Maidens were few, as

they were married at an early age, and passed from childhood into

womanhood without the intervening years which their pale-face sisters

enjoy. So soon as a young or old man desired a wife, and had settled

upon the maiden he delighted in, the parties assembled with their

friends, and after the bridegroom and all the relatives and friends had

filled a large peace pipe, and each had smoked it, the bride was

addressed as to her duties, the nuptial gifts provided by the bridegroom

were delivered to the friends, and the married pair retired to their

lodge. Polygamy prevailed among the people, but the first wife had the

pre-eminence, and exercised her authority in the lodge, much to the

confusion and sometimes to the injury of the other members of the

family.

The Nez Perce chiefs

were a notable class of men, well skilled in all the arts of diplomacy,

firm in the exercise of their authority, and generally just in all their

dealings, their loyalty to their tribe compelling them to seek the

interest of their people in preference to their own personal concerns.

If at any time a stranger of importance was introduced to the chiefs and

leading men of the tribe, the head chief, in introducing the members of

his tribe, would discriminate between them, by forbidding any who came

forward to shake hands with the stranger, simply signifying his

disapproval by a motion of the hand, which was instantly obeyed, without

any sign of retaliation.

These were valiant men

in times of war, able to cope with the strongest and most daring of

their enemies, yet never resorting to any foul methods whereby they

might take advantage of them and gain a victory. The usual war customs

were followed by them in the early days, when they united with the

Flatheads and Pend Oreilles against their foes, but after coming in

contact with the nobler elements of the civilization of the white men,

they were not slow to perceive their superiority, and consequently

adopted them in preference to some of those which belonged to the

tribes. The Nez Perces were the inveterate enemies of the Blackfeet, and

a match for them in fighting when they were aroused, which was sometimes

difficult to do, as they delighted in peace and not in war, loving to

follow some of the arts of industry, rather than wholly depend upon the

precarious livelihood of the chase. On the warpath the aged warrior wore

his amulet to protect his body from the bullets of his foes, and so long

as lie carried this with him he believed that he was invulnerable, and

his constant preservation as well as success in war gave force to his

belief. If the Nez Perce war party met a band larger than their own, or

were decoyed into the region of an opposing tribe, they would sell their

lives dearly, rather than retreat. It has been written of the Nez Perces

that they form " an honorable exception to the general Indian

character—being more noble, industrious, sensible, and better disposed

toward the whites, and their improvements in the arts and sciences, and

though brave as Caesar, the whites have nothing to dread at their hands

in case of their dealing out to them what they conceive to be right and

equitable."

Chief Joseph, whom I

have already mentioned as one of the bravest and most skilful in

statesmanship amongst all the leaders of the Indian tribes, stood forth

unrivalled for his magnanimity, eloquence, military ability and

firmness, shown in his famous retreat after the uprising of the nation.7

When the promises made by the Government commissioners had for several

years been broken, the moneys due the Indians not being paid, and

efforts made to remove them from their Reservation, he was unable to

restrain his people from rising, but heroically he placed himself at the

head of his native troops, and conducted a campaign, distinguished for

the absence of cruelty and the exhibition of talents worthy of a Roman

military leader. When the American troops were aided by their

bloodthirsty Bannacks, who were enemies of the Nez Perces, cruel modes

of warfare were introduced, the Bannacks scalping their fallen foes,

maltreating their captives, and subjecting the Nez Perce women to every

indignity. The Nez Perce refused to retaliate. They did not scalp their

fallen enemies, and the white women taken captive by them were dismissed

unharmed. When they were defeated they made preparations for their

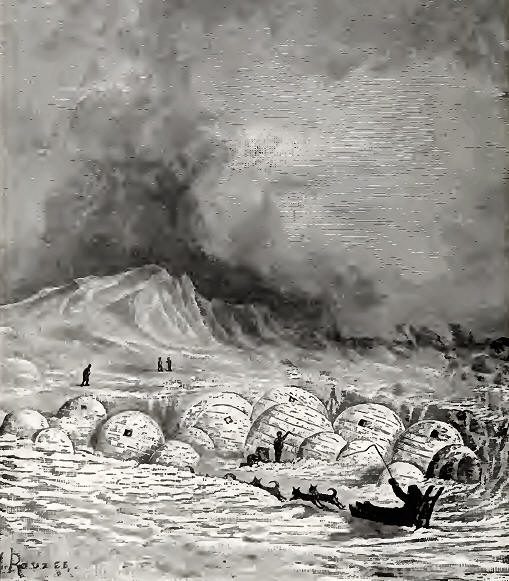

famous retreat, covering a

distance of a thousand

miles, over rugged defiles and mountainous pathways, pursued by the

hostile Bannacks. The military ability of Chief Joseph was displayed in

the famous march homeward. Gathering the women and children, the whole

members of his tribe, old and young, protected by mounted warriors, he

fought his way through the ranks of his enemies,, defeating them on

several occasions, although he was hard pressed and they were fresh and

able to obtain help to intercept him in his march. So successfully was

the retreat managed that not until they were within one day's march from

home were they overpowered, and then it was through a large force of

infantry, cavalry and artillery from Fort Keogh effectually barring

their advance. Courageous to the last, they made preparations to

withstand the attacks of the American soldiers, determined to secure

justice at all hazards, and humane thoughts and feelings prevailed, for

they surrendered on terms satisfactory to themselves. The Nez Perces of

Chief Joseph's band surrendered to General Mills in 1877, and were

removed to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to the number of four hundred and

thirty-one, where there was great mortality among them. In 1879, they

were removed to their Reserve of forty thousand seven hundred and

thirty-five acres, adjoining the Poncas, and situated on both sides of

Salt Fork of the Arkansas. General Sherman, in his report of the Nez

Perce war, said : " Thus has terminated one of the most extraordinary

Indian wars of which there is any record. The Indians throughout

displayed a courage and skill that elicited universal praise; they

abstained from scalping, let captive women go free, did not commit

indiscriminate murder of peaceful families, which is usual, and fought

with almost scientific skill, using advance and rear guards, skirmish

lines and field fortifications."

These people were

sympathetic and respectful, their love for their own reaching beyond

death, as is shown by their mortuary customs. Many of the Indian tribes

are afraid of the spirits of the dead, and resort to different methods

of warding off the attacks of their deceased foes. Sometimes they

believe that those who were formerly their relatives are now

antagonistic to them, which may arise from their belief that they will

repay them for any slight done upon earth, and now that they dwell in

the spiritual world, they are able to inflict injuries upon them which

the living cannot well ward off. As the Nez Perces roamed over the

mountains and prairies, they frequently passed the graves of their

friends, and always with respect, though sometimes with fear. When they

came near to a grave which they had not visited for a long time, the

women and children would gather around it and wail bitterly for the

dead, and the men, silent and sad, mourning their loss, would .stand at

a short distance in communion with the loved and lost.

Two years ago, in the

Pincher Creek country in Southern Alberta, a Nez Perce Indian was

condemned to death for the murder of another member of his tribe, a

medicine man. There was some excitement over the occurrence, happening,

as it did, not far from a white settlement; yet the native belief seemed

to point to the fact that the medicine man had used his power for

causing the death of a patient, a relative of the murderer. Amongst the

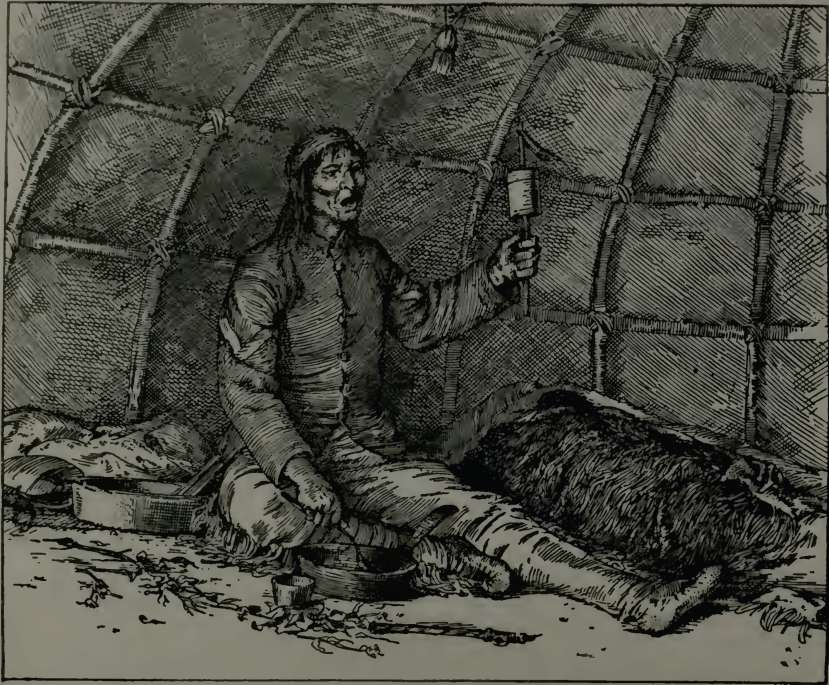

Indian tribes the medicine man is an influential personage, using

hypnotic means for destroying his foes, and curing those favorable to

him, or who paid him well. The tahmanous of the shaman or medicine man

have destroyed many persons who might have lived. Among some of the

native tribes of the south, especially the Papagos, the medicine man,

failing to cure a leading chief when he has died from any disease,

instead of being killed in battle, is taken out before the whole camp

and shot. Among the Nez Perce and other tribes of the north, he

exercises great power over the people, and it is seldom that anyone

becomes courageous enough to retaliate, believing that the shaman is

powerful, and will inflict some injury upon them unless they submit to

his will.

The Nez Perce women are

industrious, neat in their dress, active in their habits, and when

pressed in time of war heroic in defence of their husbands, children, or

friends. What exciting times the natives have at lacrosse, horse racing,

shooting, running on foot, guessing, and throwing the arrow and wheel.

The Nez Perces have a game which I have oftentimes seen played among the

Blackfeet, although not in the same fashion, which is guessing with a

small piece of wood. Instead of a single pair, as amongst the Blackfeet,

the Nez Perces arrange themselves in two parties, sitting opposite to

each other, and a small piece of wood is passed from hand to hand of the

other party, the members of which guess, until when rightly guessed,

they become the possessors of the article. While the game is in motion,

the parties and those not engaged in the game are betting, and some of

these bets are quite large. Meanwhile the contestants sing a weird

chant, beating on any article with short sticks which will produce a

noise.- Singing, beating time, guessing, rolling and swaying the body,

in a continual state of excitement, the game proceeds until the one

party defeats the other members opposed to them. The onlookers, whites

and Indians, become deeply interested in the game, and share in the

excitement, watching it eagerly, and animated by the furious motions of

the parties in the game.

A singular instance is

told of the desire of the Nez Perces for knowledge. They had heard of

the superiority of the race of white men, and learning that this arose

from the fact, that they had a religion that was better than that of the

Indians, they despatched a delegation of two of their chief men, named

"Rabbit-Skin-Leggings" and "No-Horns-on-his-Head," to St. Louis to

inquire concerning the truth of the report. The object of their journey

was made known through Mr. Catlin, the artist, which was "to inquire for

the truth of a. representation which they said some white men had made

among them, that our religion was better than theirs, and that they

would all be lost if they did not embrace it."

These men were

entertained by the people of St. Louis, some of whom wondered at the

intense eagerness of the men, who had made a long journey, to learn

something of the Christian's God, and the peculiar religion of the white

man. On their journey homeward, one of these men died, but the other

lived to tell his friends that the report they had heard was true, and

in a short time white men would come to tell them the truths of the

wonderful Book, and the story of the blessed Christ.

The story of this

delegation, sent by the Nez Perces upon such a long journey, produced a

deep impression upon the minds of the Indians, and induced the white

people to think seriously of their duty to care for them. Within two

years after the visit of the Nez Perces to St Louis, the American Board

and the Methodist Episcopal Missionary Society sent missionaries to

Oregon to teach the people the truth of the Gospel.

Some years previous to

this visit, some of the Hudson's Bay Company's employees, residing at

Fort Walla-Walla, had introduced some of the truths and forms of the

Roman Catholic religion amongst these natives, and the influence of

these things had exerted a decided change amongst some of the bands.

They gave up in a great measure the practice of polygamy, and sought to

live moral lives. The Christian ceremonies had become Indianized, yet

some of the people strove to practice the precepts their had been

taught. Some of the Shoshonees observed the change which had been

affected through following the white mans religion, and they began to

imitate the Nez Perees. They observed Sunday, engaged in devotional

dances and chants, and followed the other ceremonials of the Nez Perces.

This imitation sprang from a desire to gain superiority over their rival

tribes, believing that in this form of religion la}' the secret of the

white man's power. Some years ago I met an intelligent Nez Perce chief,

named Johnson, and made inquiries concerning his religious belief, but

found that he still retained his native ideas, and followed not the

teachings of the Christian religion. In their native condition this

tribe was devout, always prefacing their hunts with religious rites and

prayers to the great spirit for safety and success.8

Indeed, in a starving condition they attended to their sacred days and

pious ceremonies before seeking food.

Captain Bonneville,

having witnessed their piety on several occasions, said: "Simply to call

these people religious would convey but a faint idea of the deep hue of

piety and devotion which pervades their whole conduct. Their honesty is

immaculate, and their purity of purpose and their observance of the

rites of their religion are most uniform and remarkable. They are

certainly more like a nation of saints than a horde of savages." Their

religion was infused with a spirit of fear, and they felt that they were

surrounded by evil spirits, who sought to injure them. Their medicine

men invoked the aid of their guardian spirits, and they wore on their

persons amulets to protect them in time of danger.

The Protestant

missionaries who went among them labored hard to teach them the

doctrines of the Christian religion, and they were encouraged in their

efforts by the change in the lives of the people. A sad fate befel the

Rev. Dr. Whitman, who labored with success among this tribe, some of

whom were aroused through false reports to rise against the white

people, .and this faithful missionary was stricken down by a tomahawk,

in the hand of an unfriendly Indian, in the year 1849. He had labored in

the country along with the Rev. Mr. Spaulding and other missionaries

since 1836, and so great was his zeal on behalf of the people and the

country that he said, when remonstrated with for the intensity of his

labors, " I am ready, not to be bound only, but to die at Jerusalem or

in the snows of the Rocky Mountains for the name of the Lord Jesus or my

country."

Some years after the

missionaries had begun their labors in Oregon, a traveller gave an

account of his experience with a Nez Perce guide, named Creekie, which

is of interest:

"Creekie was a very

kind man. He turned my worn-out animal loose, and loaded my packs on his

own; gave me a splendid horse to ride, and intimated, by significant

gestures, that we would go a short distance that afternoon. I gave my

assent, and we were soon on our way. Having ridden about ten miles we

camped for the night. I noticed, during the ride, a degree of

forbearance toward each other which I had never before observed in that

race. When he halted for the night the two boys were behind. They had

been frolicking with their horses, and as the darkness came on lost the

trail. It was a half-hour before they made their appearance, and during

this time the parents manifested the most anxious solicitude for them.

One of them was but three years old, and was lashed to the horse he

rode; the other only seven years of age —young pilots in the wilderness

at night.

"But the elder, true to

the sagacity of his race, had taken his course, and struck the brook on

which we were encamped within three hundred yards of us. The pride of

the parents at ' this feat, and their ardent attachment to the children,

were perceptible in the pleasure with which they received them at their

evening lire, and heard their relation of their childish adventures. The

weather was so pleasant that no tent was spread. The willows were bent,

and the buffalo robes spread over them. Underneath were laid other

robes, on which my Indian host seated himself, with his wife and

children on one side and myself on the other. A fire burnt brightly in

front. Water was brought, and the evening ablutions having been

performed, the wife presented a dish of meat to her husband and one to

myself. There was a pause. The woman seated herself between her

children. The Indian then bowed his head and prayed to God.

"A wandering savage in

Oregon calling on Jehovah in the , name of Jesus Christ! After the

prayer he gave meat to his children and passed the dish to his wife.

While eating, the frequent repetition of the words Jehovah and Jesus

Christ, in the most reverential manner, led me to suppose that they were

conversing on religious topics, and thus they passed an hour. Meanwhile

the exceeding weariness of a long day's travel admonished me to seek

rest. I had slumbered 1 know not how long, when a strain of music awoke

me. The Indian family was engaged in its evening devotions. They were

singing a hymn in the Nez Perce language. Having finished, they all

knelt and bowed their faces on the buffalo robe, and Creekie prayed long

and fervently. Afterward they sung another hymn and retired. To

hospitality, family affection and devotion, Creekie added honesty and

cleanliness to a great degree, manifesting by these fruits, so contrary

to the nature and habits of his race, the beautiful influence of the

work of grace on the heart."

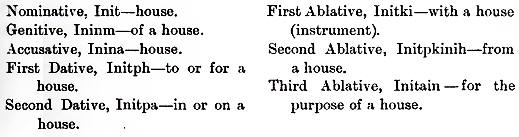

The Nez Perce language

belongs to the Sahaptin family, of which there are two principal

languages and several dialects. It is throughout an inflected language,

the nouns having eight cases, and the verb surpassing in the variety of

its forms and the beauty and minuteness of its distinctions the Ayran

and Semitic. There are six moods and nine tenses, with many verbal

forms, revealing a richness that evinces strong intellectual powers in

the members of this tribe.

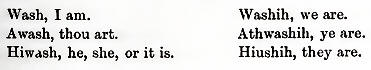

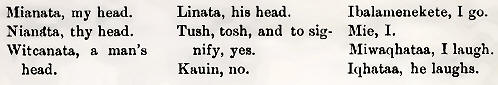

The following samples,

taken from Horatio Hale's "Development of Language," will give the

reader a slight idea of the Nez Perce language:

The verb is rich in

forms, the primary or simple conjugation of the verb " to see "

embracing no less than forty-six pages of manuscript, and this does not

include the six derived conjugations, each of which possess all the

variations of the simple verb.

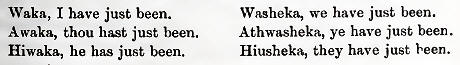

The following example

of the first three tenses of the substantive verb, taken from the same

source as those aforementioned, will suffice to show the construction of

the language in its simplest forms:

Present Tense.

Present Past Tense.

Remote Past Tense.

Far from the madding

crowd in the centres of population dwells the remnant of this powerful

tribe, striving upon their Reservation to adapt themselves to their new

circumstances, forced upon them by the greed of the- white man, yet the

native ability displayed in the days of yore abides, and they evince in

their crushed condition habits of industry and a 1 hopefulness which few

of the members of the pale-faced tribes of men could show under

oppression and the removal of incentives to independence and an

honorable position in life. The silver lining to the cloud lies in the

changing attitude of the English-speaking races toward the American

Indian race, brought about through the loving energy of consecrated

Christian men and women, striving to educate their fellows toward a due

appreciation of the abilities of these people, a recognition of the

rights of fellowship of the human race, and the obligations of Christian

society.\

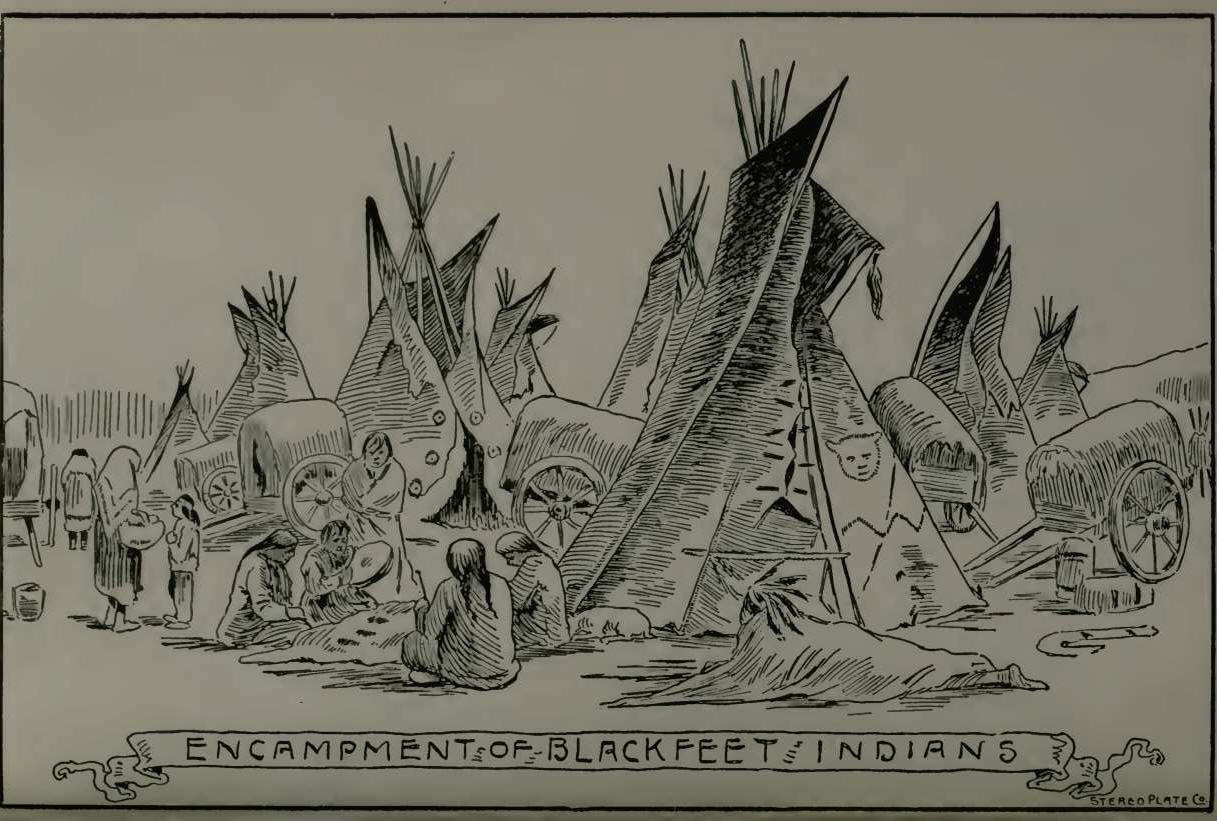

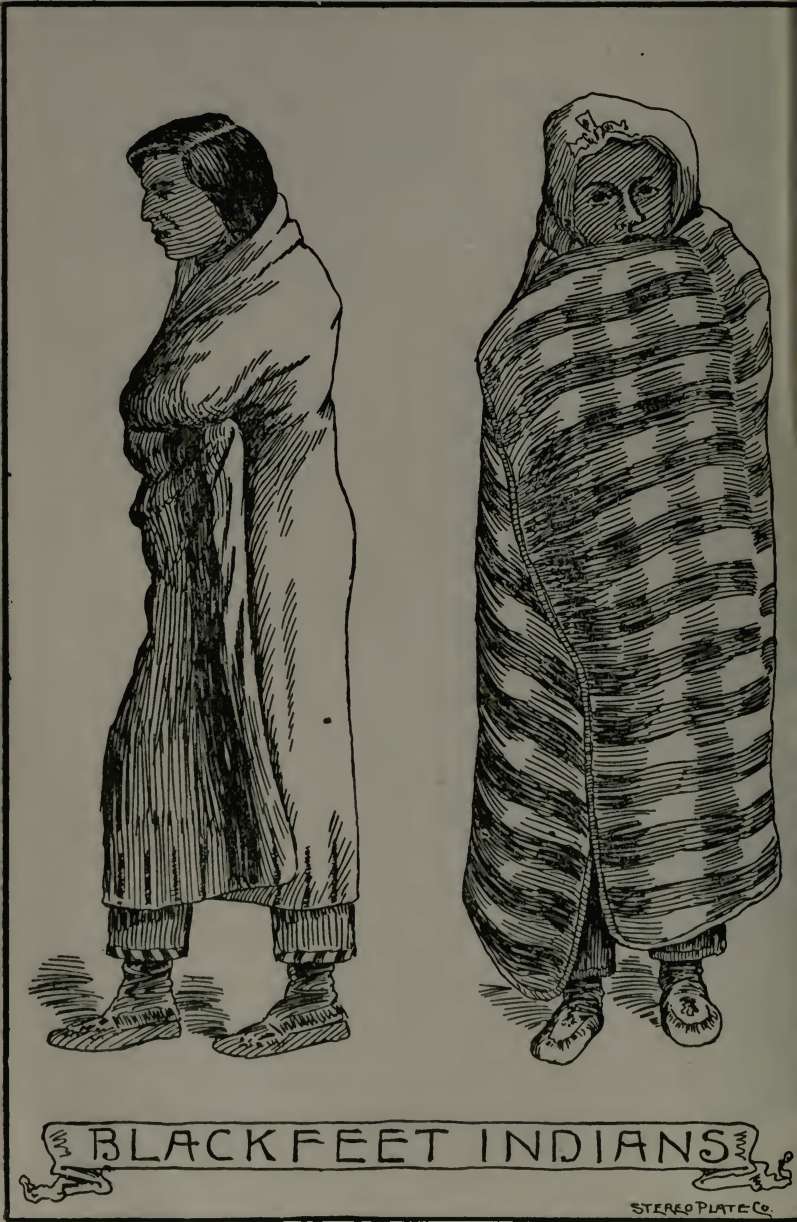

THE BLACKFOOT INDIANS.

In the ancient and

happy days of yore there roamed over the western plains, from the lied

River to the Rocky Mountains and beyond, numerous tribes of prairie

Bedouins, in quest of food and eager for war. Ojibways, Crees,

Blackfeet, Sioux, Shoshonees, Gros Ventres and other savage peoples

scoured the eastern plains with warlike intent, delighting in their

unhampered liberty, and claiming the boundless prairies as their

rightful possession. Not the least in number and prowess was the

Blackfcot Confederacy, comprising the Blackfeet, Bloods and Piegans.

Frequently in these modern days have I met the aged Blood Indian

warrior, with his hand upon his mouth, singing his song of sadness; and

when suddenly I have called upon him to explain the cause of his grief,

he has ceased his monotonous plaint and turned to me, saying, "'Niokskatas!'

Where are our noble warriors of former days? Where are the people that

assembled in our camps by thousands? Where are the buffalo that covered

our plains?" Sorrowfully was I compelled to say; "They are gone!" "See,"

said he, "the fences of the white man stopping our trails. See the white

man's cattle upon the prairies, and the towns everywhere throughont our

land. Niokskatas! Our great men are gone, our people are dying, our

lands are no longer ours, and we, too, shall soon pass away!" Resuming

his song he has continued his journey, a weary and disheartened old man.

The Blackfeet tell us

in their traditional lore that they came in the distant past from the

north, from some great lake, supposed to be Lake Winnipeg. When the