|

CROWFOOT

THE famous chief of the

Blackfeet was one of the most striking personages in the Canadian

North-West. The dignified leader of his own tribe, lie was also the

acknowledged chief of the Blackfoot Confederacy. I was deeply impressed

with his sterling qualities and abilities as a commander when first I

saw him. The Bloods and Piegans always spoke in glowing terms of his

eloquence and wise administration, corroborating Natosapi's (Old Sun's)

opinion expressed at the making of the treaty, "Crowfoot has been called

by us our Great Father." When they discussed any of his measures for the

welfare of his people, they invariably finished by saying, "Crowfoot is

a wise man." The father of Crowfoot was chief of the Blackfeet—a man of

distinguished powers and of. great influence. He was called

Akautcinikasima, meaning "Many Names," a word composed of akauo, "many,"

and tcinikasi-mists, "names." His mother was a Blood Indian woman.

Crowfoot was born near the Blackfoot Crossing, about the year 1826.

Although the son of the chief, he possessed as a boy no special favors

such as belong to royalty, the native laws compelling every member of

the tribe to win his laurels, and permitting none to be exempt from the

duties of his station. There is no social distinction in the camp, but

there are civil and military positions, with their respective duties,

and obedience and respect are given to those officials during the

performance of their duties. The natives are a democratic people,

without any faith in an aristocracy of wealth. They are, however, deeply

attached to an aristocracy of ability, valor and character. As a boy in

the camp he felt a hereditary pride in belonging to such a warlike tribe

as the Blackfeet, whose name brought terror to the Crees, Ojibways,

Saulteaux and Shoshones sixty years ago, and as the member of a family

of chiefs there was stirred in his bosom an ambitious desire to win a

worthy place among his people.

This was the emotion

which aroused the hearts of the young men in general, but this youth

seemed to feel it more deeply than any other member of his race. This

was shown when he was only thirteen years of age, an opportunity having

occurred for him to join a party going out on a war expedition. The

youthful warrior exhibited such brave qualities, and was so energetic on

the warpath, that his name was changed for that of Kaiosta, meaning

"bear ghost," compounded of the words Kaio, a bear, and Staa, a ghost or

spirit. He was honored among his people for the spirit manifested, which

aroused his ambition still more to merit their applause by greater

deeds. He had a brother older than himself who bore the illustrious name

of Crowfoot, on account of his successful expedition against the tribe

of Crow Indians. The Blackfeet designed the making of a treaty with the

Snake Indians, and fourteen of their bravest and wisest men were

despatched for that purpose, Kaiosta's brother being one of the number.

The Snake Indians basely ignored the Indian laws relating to the bearers

of peace, and treacherously slew them.

Chief Many Names and

the tribes of the Blackfoot Confederacy were deeply incensed at this act

of cruelty in defiance of the customs of war, and determined to punish

them for their cowardice and knavery. A large war party was organized

and started for the country of the Snakes in Montana. Kaiosta,. aroused

by fraternal love and youthful valor, joined the party. They found the

Snake Indians prepared to receive them, but the Blackfeet outnumbered

them, and fought so furiously that the Snakes were ignominiously

defeated. So great was the bravery of the youthful son of Many Names,

that again his name was changed, and he received the one belonging to

his deceased brother, and that by which he was ever afterward known,

namely, Crowfoot. The significance of this name is found in its allusion

to the Crow Indians, who were enemies of the Blackfeet.

Esftpomitqsikaw,

meaning "Crowfoot," is composed of Esupo, the name of the Crow Indians

in the Blackfoot tongue, omuqsim, "large," and oqkuts, "a foot." We have

then in the name Esupo, Crow, muqsi, large, and kaw, foot. By the

euphonic laws of the language the intervening letters and syllables are

elided in the composition of the name. It is composed of the word Crow,

with the two words signifying the one who has a large foot. When

Crowfoot reached manhood he developed striking physical characteristics,

which marked him as no common man. He was above medium height, with a

high forehead, thin lips firmly compressed, an aquiline nose, high cheek

bones, piercing grey eyes, and a face that suggested commanding

qualities. As he softly strode over the prairie, he had the dignified

mien of the leader of men, a modern Roman among savages. At the sun

dance he aroused the warlike emotions of young and old by the recital of

his brave deeds. Foremost in the fight and the last to retreat, he led

his warriors through many a successful fray, and they always returned

with increased admiration for his courage and skill.

He succeeded his father

as chief of the tribe, and was subsequently acknowledged as the head of

the confederacy. Before being called to this position he distinguished

himself at the* Battle of Three Ponds, situated between the Red Deer and

Battle rivers. The Crees were enemies of the Blackfeet, and seized every

opportunity of attacking them. Stealthily they approached the camp of

Natos (the Sun) about midnight on the 3rd of December, 1866, and

attacked the people, who were few in number. In the most critical

juncture, when the Crees had almost gained a victory, the voice of

Crowfoot was heard shouting to his warriors as he dashed upon the Crees.

His sudden appearance and great prowess renewed the courage of the

Blackfeet, and the Crees were soon overcome. The victorious Blackfeet

rejoiced in the intrepid valor of Crowfoot, who had saved them at a time

when destruction stared them in the face, and he was raised in the

estimation of his people. Only a few years later, the Blackfeet, Bloods

and South Piegans were attacked near Lethbridge, on the Belly River, by

a war party of Crees and Assiniboines. The Blackfeet and Bloods were

camped between the trading-posts called Whoop-up and Kipp, and the South

Piegans were stationed on the St. Mary's River. The Blood camp was

attacked and a few Indians killed. The Bloods were few in number and

unequal in the contest with the combined force of Crees and Assiniboines,

and runners were despatched to arouse the Piegans, who speedily came to

their aid. The Blackfeet, Bloods and Piegans were better armed than

their enemies, and having united their forces, the Crees were compelled

to retreat towards Belly River, opposite the present site of Lethbridge.

They placed themselves in position in one of the coulees on the high

banks of the river, and the Blackfeet, with their confederates, found a

similar position in a parallel coulee about three or four hundred yards

distant. The opposing forces fought desperately for four or five hours,

when the Crees began to retreat toward the river. Swiftly they were

followed in a confused mass down the coulee, the war cries of the

pursuers mingling with the death yells and groans of the wounded and

dying. The Crees plunged into the river still closely pursued, while

many of the victors stood upon the banks and shot down the helpless

swimmers. Almost at the base of the high bank on the opposite side of

the river the remnant made a last stand to fight for life, and until

darkness compelled them to desist the battle continued. A formal treaty

was made between the tribes in the year following, and this has been

kept until the present time.

Crowfoot was

distinguished as an orator among his people. He was slow and deliberate

in speech and a man of few words. His language was expressive, and

sometimes full of beautiful imagery. It is impossible to gain a true

idea of his power as a speaker from his addresses to Government

officials and members of the white race, as these were harangues, and

generally dealt with questions affecting the temporal interests of his

people, these belonging to the petty concerns of everyday life, such as

food and clothing. It was when discussing grave questions in the native

council that he shone as an orator, and his genius far surpassed the

strongest intellects among his people. I have listened to some of the

native orators, and have been charmed with the beautiful and expressive

phraseology, the dignified attitude, the piercing eye, and graceful

gestures, and the effect produced upon the people.

At the Blackfoot Treaty

with the Government, made at Blackfoot Crossing, in 1877, Crowfoot

addressed Lieutenant-Governor Laird and the Commissioners as follows:

"While I speak be kind and patient. I have to speak for my people, who

are numerous, and who rely upon me to follow that course which in the

future will tend to their good. The plains are large and wide, we are

the children of the plains, it is our home, and the buffalo has been our

food always. I hope you look upon the Blackfeet, Bloods, and Sarcees as

your children now, and that you will be indulgent and charitable to

them. They all expect me now to speak for them, and I trust the Great

Spirit will put into their breasts to be a good people—into the minds of

the men, women, and children, and their future generations. The advice

given me and my people has proved to be very good. If the police had not

come to the country, where would we be all now ? Bad men and whiskey

were killing us so fast that very few, indeed, of us would have been

left to-day The police have protected us as the feathers of the bird

protect it from the frosts of winter. I wish them all good, and trust

that all our hearts will increase in goodness from this time forward. I

am satisfied! I will sign the treaty." The difficulty of presenting

Crowfoot as a distinguished speaker may be learned from the fact that in

addressing those who did not understand his native tongue, he had to

speak a sentence at a time, which was then interpreted, and consequently

his thoughts were somewhat disconnected, and his flow of language

interrupted.

When the correspondent

for the Mail visited the Blackfoot Crossing, Crowfoot was interviewed,

and his skill in dealing with men is seen in the manner in which he

dealt with the subjects mentioned to him. He said: "It always happens

that far-away countries hear exaggerated stories of one another. The

distance between them causes the news to grow as it circulates. I often

hear things of far-off places, but I do not believe them; it may be very

little, and be magnified as it goes. When I hear such news about you as

you hear about me, I don't believe it; but I go to the Indian agent, or

some one else in authority, and ask and find out the truth. "Why should

the Blackfeet create trouble ? Are they not quiet and peaceable and

industrious? The Government is doing well for them and treating them

kindly, and they are doing well. Why should you kill us, or we kill you

? Let our white friends have compassion. I have two hearts—one is like

stone, and one is tender. Suppose the soldiers come, and, without

provocation, try to kill us—I am not a child—I know we shall get redress

from the law. If they did kill us, my tender heart would feel for my

people."

When asked about his

grievances, he replied: "There is no grievance, except the burning of

the grass on our Reserve by the sparks from the railway, which has been

reported by the agent. Last year the grass was burned, and the year

before, too. Great damage was caused. Our horses lost their food, and

some were lost by going on the heated ground. The first year we asked no

recompense; but last year we asked for damages, and have yet received no

answer. If this harm was done in the white man's country it would be

redressed. If my people burned other people's grass, I should speak to

them, and make them give redress. Mr. Dewdney told me to tell the agent,

Mr. Begg, of any grievance, and I told him of this; but I didn't say

anything till I saw the misery and destitution the tire had caused. It

nearly burned our own houses. This is my only grievance."

It was in the councils

of the nation and in dealing with his own people that Crowfoot's

abilities as a leader were specially seen. He had a strong intellect, a

good knowledge of human nature, and was a wise and successful native

diplomat. It was le who suggested plans for bettering the condition of

his people; and, in times of difficulty, he saw a way of escape, when

others failed to provide a remedy. He was intensely patriotic. He loved

his people sincerely and the customs of his race. Always friendly toward

the white people, and never tired )f urging the natives to imitate their

virtues and eschew their prices, setting before them the benefits of

industry and a wise conformity to their changed conditions through the

advent of civilization and the departure of the buffalo, he still

counselled hem to follow the native traditions, and maintain their

tribal unity. He wisely foresaw the impossibility of making civilized

white men from Indians; and he could not forget he prestige of former

days. Unto the last he remained deeply attached to the faith of his

fathers; and his people olio wed him in their adherence to their native

faith. The and in which they dwelt was filled with sacred memories,

every hill and valley marking a battle field, burial place of heir loved

ones, or honored with some tradition which was dear to their hearts.

The policy of Crowfoot

was peaceful, and his wise administration revealed the consummate

shrewdness and sterling character of the man. How changed was the

condition of affairs from the former days when Chief Many Names could

lead his thousands to war, and the latter days when Crowfoot, in his ►Id

age, reigned over a few savages upon an Indian Reserve, ^mall-pox had

slain its hundreds, the buffalo were no more, the white race had invaded

the land, planting towns, laying rail-roads, and with the blessings of

civilization, bringing in its rain numerous diseases and deep-rooted

vices, which sapped be foundations of native morality, and sent many of

the noble sons and daughters of the red race to untimely and dishonoured

graves.

Some of the Indians

entertained grave fears, and held superstitious ideas about the railroad

before it reached their country; but Crowfoot believed that it was a

waggon on wheels, made by man without any supernatural power. He stood

almost alone in his belief until the people saw it for themselves. When

he visited the east he was entertained at Winnipeg, Ottawa, .Montreal

and other important places. During his visit to Montreal, Sir Win. Van

Horne, in the name of the company, informed him that a perpetual pass

would be granted him over the Canadian Pacific Railroad. This was sent

him subsequently, and acknowledged by the chief. In reply to the address

of the railway officials he said, "My heart has always been loyal. I

love the pale-faces. They are good friends to me and to my people. I

would not let my young men go on I the warpath. When Indians tell me

lies I shut my ears. I will only believe in wrong when the white man

tells me himself. When I return my young men will protect the railway

and the fire waggons."

Owing to various rumors

of dissatisfaction among the Indians, it was thought wise by the

Government to send some of the chiefs of the different tribes 011 a

visit to the towns and cities of Ontario and Quebec, that they might

learn something of the wealth, power, numbers and spirit of the white

people. Crowfoot was one of the chiefs selected for that visit. The

Mayor and Council of each of the cities received the native deputations

and honorably entertained them.

As he journeyed

eastward, upon learning that Lake Superior was not the sea, he

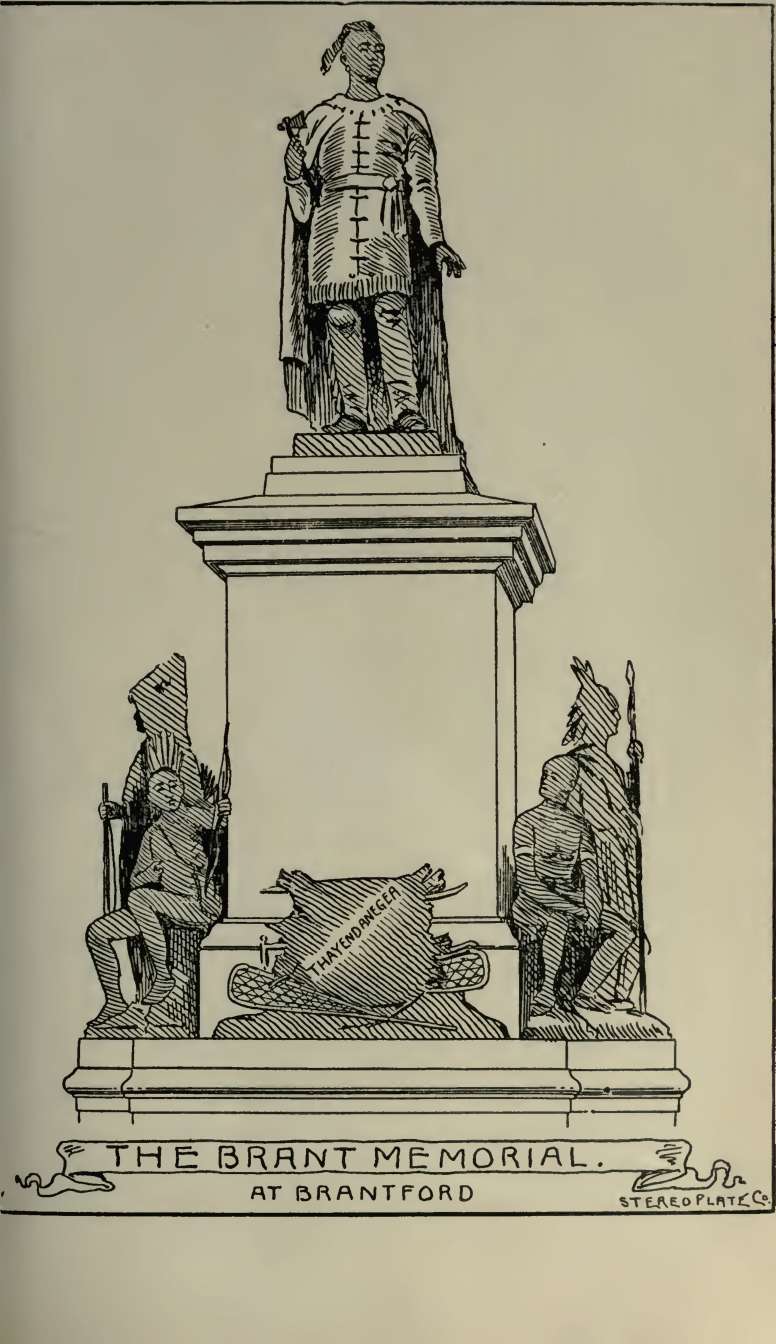

christened it " The Little Brother of the Sea." Crowfoot desired the

Blackfeet to be represented at the unveiling of the Brantford monument

to Chief Joseph Brant, and as he was anxious to see his people, and

could not wait for the ceremony, he confided to the care of Mr.

L'Heureux, the interpreter, four historic arrows, to be given to tin*

Iroquois. Mr. L'Heureux is authority for the statement that these arrows

are connected with a native legend, that the earth was once covered with

water, and all the tribes were gathered on a mountain. The white, black

and yellow tribes were on the top of the mountain, but the red men were

in the inside. After a time the wise men among the Indians bored a hole

out of the side of the mountain, and, looking out, saw a white

swan floating on the

waters near the mountain. The swan bore four arrows, pointing to the

north, south, east and west The red men killed the swan and captured the

arrows, which possess a hidden meaning for the Indians. The arrows

conveyed to the Iroquois represented the captured ones of the legend The

Iroquois received the arrows with due solemnity, and sent to Crowfoot a

small string of wampum beads. Crowfoot's influence was unlimited in his

own tribe, but even beyond the confederacy his name was honored by the

members of other tribes, The white people admired his. policy in dealing

with the natives, and respected him for his abilities and his attitude

toward the white race. Some doubts were entertained about Crowfoot's

loyalty, which were, however, set at rest by his actions during the

Rebellion, and his own declarations afterward upon several occasions.

When asked whether Riel had ever asked him to join in revolt, he said,

"Yes; over in Montana in the winter of 1879 or the spring of 1880. He

wanted me to join with all the Sioux, and Crees, and half-breeds. The

idea was to have a general uprising and capture the North-West, and hold

it for the Indian race and the Metis. We were to meet at Tiger Hills, in

Montana; we were to have a government of our own. I refused, but the

others were willing; and then they reported that already some of the

English forts had been captured. This was a lie. Riel took Little Pine's

treaty paper and trampled it under his foot, and said we should get a

better treaty from him. Riel came also to trade with us, and I told my

people to trade with him, but not to listen to his words, lliel said he

had a mighty power behind him in the east."

In 1875, Sitting Bull

and ten of his chiefs, who had fought Custer, visited Crowfoot to secure

his help, but he firmly refused. In protesting his loyalty Crowfoot

concluded: "To rise there must be an object; to rebel there must be a

wrong done ; to do either, we should know how it would benefit us. We do

not wish for war. We have nothing to gain; but w| know that people make

money by war on Indians, and these people want war. If these people want

to incite war, or to .steal the right of warring men—that is, to fight

without the consent or knowledge of the Government—don't let them, and

when they find out that there is no profit in it, they will stop. The

Queen does not want war when there is no cause. She is not in favor of

war. Let the Government know that we favor peace, and want it. I have

done."

Crowfoot had been

failing in health for some time, and both he and his people knew that

his days were numbered. The medicine men gathered around his bed, but

their incantations and medicines availed not to bring relief. Everything

was done by the people to minister to his wants and make him

comfortable, but the end was near. He distributed his horses among his

relations. The numerous gifts he had received during his visit east were

given to his white friends. His brother, Three Bulls, he nominated as

his successor, and with an admonition to the natives to live on good

terms with the white people, on April 27th, 1890, surrounded by whites

and Indians, he quietly breathed his last. Rev. Father Lacombe performed

the burial service, and the great chief of the Blackfeet was laid to

rest amid great lamentations from his people, and sincere sorrow among

the white population. He was a noble red man, worthy the respect and

grief of a great nation, which delighted to honor him in life, and now

holds dear his memory as a sacred trust.

POUNDMAKER.

Poundmaker was one of

the ablest chiefs of the Cree Confederacy. His father was a Cree Indian,

and the early years of him who was destined to occupy a prominent place

in the councils of his nation were spent in the camps of his own people.

When but a youth he met Crowfoot at a trading party, and the Blackfoot

chief looked kindly on him. Crowfoot had lost a son whom he tenderly

loved, and mourned deeply for him, and as he gazed into the face of the

Cree lad, he saw a resemblance to the son who wa^ no more. He told the

youth that he would be a father to him, and accordingly •adopted him. He

went to the camp of the Blackfeet with Crowfoot, and dwelt with him in

his lodge for several years. In manhood he returned to his own people,

married among them, and soon rose to distinction as a brave warrior and

wise statesman.

The Cree country lies

to the north of the Blackfeet, and the people, though distinct tribes

and belonging to different confederacies, are members of the Algonquin

stock. There have never, within the memory of man, existed cordial

relations between these tribes, but they have always been most

inveterate enemies toward each other. Cessation of hostilities has only

been enjoyed when they have been tired of warfare and a treaty has been

made. Wars were frequent between them, and they were eager for every

opportunity, upon the slightest provocation, of attacking the camps. The

intellectual ability of Poundmaker gave him pre-eminence, which he

exerted for the purpose of securing peaceful relations between the

tribes, and it was chiefly through his influence that a treaty was made

between them. Little Pine, Big Bear and some other chiefs were always

anxious to go on the warpath, and they seemed to have special delight in

harrassing the Blackfeet.

The policy of

Poundmaker, like that of Crowfoot, was peaceful, and with his influence

on the side of justice, he maintained peace when others were eager for

war. He was a fine specimen of the Cree Indian—tall and slender, a high

forehead, a Grecian nose, intelligent countenance, free from any signs

of coarseness or sensuality, and a body well formed, marked him as no

common man. His dignified bearing and quiet demeanour struck the visitor

to his Reserve, and these stamped him as a man wise in council,

intensely devoted to his people, and strong to command the warriors who

were deeply attached to him. Pound-maker's Reserve was situated about

thirty miles west of Battleford, on the south side of Battle River, and

its area was thirty square miles. Possessed of an independent spirit,

and accustomed to a nomadic life, he did not take kindly to farming

operations, and was none too submissive to the plans of the Government

toward inducing the Indians to become self-supporting. He consequently

was considered to be troublesome, which arose in a great measure from

failing to see the benefits which would result from leading an

agricultural life. When once convinced that it would be beneficial to

his people to adopt the new mode of living, he was not slow to avail

himself of the helps at hand, and he worked industriously himself and

encouraged his young men to forsake their roving life and follow his

example. As he was born to rule, and not to serve, and was accustomed to

dictate instead of being instructed, it was not always easy to manage

him.

The chiefs are not

arbitrary leaders, working out their own plans without consulting the

people; but, in the councils, the wishes of the people are known through

the minor chiefs, and the head chief acts as spokesman for the tribe in

all important matters. Sometimes the head chief is compelled to follow

instead of leading, and to acquiesce in plans which his own judgment

does not approve, and blame is often attached to the chief by persons

ignorant of the customs of the natives for his attitude on public

questions. Poundmaker was sometimes placed in this anomalous position,

assenting to schemes which the people believed were right, and he was

not in agreement with them. He wavered not, however, in the performance

of his duty, when the members of his tribe through their chiefs had come

to a decision on some tribal matter, or policy of the Government. At the

Carleton treaty, made between the Crees and the Government in the year

1876, he agreed to the propositions of the Commissioners, and signed the

treaty. He said on that occasion: "We have heard your words that you had

to say to us as the representative of the Queen. We were glad to hear

what you had to say, and have gathered together in council and thought

the words over amongst us. We were glad to hear you tell us how we might

live by our own work. When I commence to settle on the lands to make a

living for myself and my children, I beg of you to assist me in every

way possible. When I am at a loss how to proceed I want the advice and

assistance of the Government. The children yet unborn, I wish you to

treat them in like manner as they advance in civilization like the white

man. This is all I have been told to say now. If I have not said

anything in a right manner I wish to be excused. This is the voice of my

people." The people agreed to all the offers of the Commissioners, but

before signing the treaty, Poundmaker wished to understand everything in

a definite manner, and again addressed the Commissioners: "I do not

differ from my people, but I want more explanation. I heard what you

said yesterday, and I thought that when the law was established in the

country it would be for our good. From what I can hear and see now, I

cannot understand that I shall be able to clothe my children and feed

them as long as the sun shines and water runs. With regard to the

different chiefs who are to occupy the Reserves, I expected they would

receive sufficient for their support. This is why I speak. In the

presence of God and the Queen's representative I say this, because I do

not know how to build a house for myself. You see how naked I am, and if

I tried to do it, my naked body would suffer. Again, I do not know how

to cultivate the ground for myself; at the same time, I quite understand

what you have offered to assist us in this!"

When Governor-General

Lord Lorne visited the North West in 1881 Poundmaker expressed his

loyalty, and he was honorably attached to the Viceregal party, with whom

he travelled for some time, on their journey through the country. Among

the chiefs who deeply impressed the members of the Viceregal party with

his native eloquence, intellectual power, wisdom and dignity, was the

aged Cree chief, Mistawasis (Big Child). Though small of stature, lie

was one of the most influential chiefs of the Cree Confederacy. His

address to the Governor-General on matters relating to his Reserve and

the people who acknowledged his authority reveals the mental power of

the leaders among the Crees. It is as follows: "I am glad that God has

permitted me to meet the Governor. I feel flattered that it was a

governor who put this medal on my neck. I did not put it on myself. We

are the children of the Great^Mother, and we wish that through her

representative, our brother-in-law, she would listen for a little while

to our complaints, and sympathize with our sufferings. I have no great

complaints to make, but I wish to make just a few remarks concerning our

property. The kindness that has been shown to us is great; but, in our

eyes, it is not enough to put us on our feet. In days gone by the

buffalo was our wealth and our strength, but he has left us. In those

days we used the horse with which to chase the buffaloes, and when the

buffaloes left us we thought we might use the horse with which to follow

after other game. But we have lost many of our ponies with the mange,

and we have had to sell others; and when I look around me, and see that

the buffaloes are gone, and that our ponies are no longer left to us, I

think I and my people are poor, indeed. The white man knows whence his

strength comes, and we know where we require more strength. The strength

to harvest the crop is in animals and implements, and we have not enough

of these. If our crops should be enough to keep us alive, we would not

have the means with which to harvest them. We would very much like more

working cattle, and more farming implements. I would beg also that, if

possible, a grist-mill should be put up somewhere within our reach, so

that we can have our wheat ground into flour, and our other crops

ground. I do not speak for myself, but for those poor people behind me.

I am very thankful that I am able to see the Governor-General in my old

days. He has come just in time that I may see him before I die. Many a

time have I been in terrible straits for food for myself and my people,

but I have never yet been angry about it, for I knew the Indian Agent

was a good friend to us, and that he always acted on the instructions

left for him, which he was bound to obey. Often have I been sorely

perplexed and miserable at seeing my people starving and shrunken in

flesh, till they were so weak that, with the first cold striking them,

they would fall off their feet, and then nothing would save them. We

want teachers to instruct and educate our children; we want guns and

traps and nets to help us to get ready for the winter. We try to do all

that the farm instructor has told us, and we are doing the best we can;

but, as I said before, we want farming implements. I do not speak for

myself, as I am getting old, and it does not much matter for me, but I

speak for my people, and for my children and grandchildren, who must

starve if they do not receive the help that they so much need."

Poundmaker was

intensely loyal, although his attitude at times seemed to express

dissatisfaction and disloyalty; but the young men on his Reserve were

athletic fellows, who loved the warpath, and the memory of the brave

deeds of their forefathers kept alive their military ambition. The

influence of Riel, the rebel leader, quickened the desires of the young

men for power and glory, and Poundmaker was swayed by the attitude of

his warriors.

The rebellion of 1885

found Poundmaker's warriors arrayed against the Government, when they

pillaged Battleford and fought the soldiers at Cut Knife Hill, on his

Reserve. He deeply regretted the position which he was compelled to

assume, and on May 26th, 1885, he surrendered to General Middleton at

Battleford. He was tried at Regina for participating in the rebellion,

and, ignorant of the law, he made an eloquent appeal in self-defence. In

a few dignified and manly sentences he addressed the Judge: "Everything

I could do was done to stop bloodshed. Had I wanted war, I should not be

here now —I should be on the prairie. You did not catch me. I gave

myself up. You have got me because I wanted justice."

Addressing the jury, in

a passionate burst of eloquence he concluded with the words: "I cannot

help myself, but I am a man still, and you may do as you like with me. I

said I would not take long. Now I am done."

He was sentenced to

three years in Stoney Mountain Penitentiary. After being conveyed to the

prison, he learned with intense grief that, according to the rules of

the institution, his hair would be cut. He had long, black locks, of

which he was justly proud, and he besought the warden to intercede for

him that these might be spared. This was done, and the imprisoned chief

was allowed to retain his locks, which lent dignity to his presence when

engaged in the menial duties which were imposed upon him. The leader of

a savage host spent the spring and summer months working in the garden

as a common prisoner. He felt keenly the change, and his robust

constitution was sadly undermined. Brooding over his degradation induced

disease, and his condition awakened the sympathy of his enemies.

Poundmaker was a chief

of great ability. He had the skin of a Cree Indian, the visage of a

commander, and the cool and strong judgment of a white man. He was a

native Demosthenes in savage attire.

Upon the New Year's Day

following his trip with the Governor-General, he gave a feast to his

people. Every member of his band who could possibly attend, from the

missionary to the youngest babe, was there. The feast consisted of

ragout, made of buffalo meat, bacon and berries, mixed with a little

Hour, boiled buffalo meat, boiled bacon, with an abundance of berry

pies, sweet galette, and tea. There were no intoxicants of any kind.

After the feast he made the following speech to his people:

"My Friends, Parents,

Men, Women and Children,—I have called you here together to-day because

I wish to speak to you all, and to everyone of you. It is not only

to-day that I tried to please you, to help you. In all my travels since

the treaty— but especially last summer—only one thought busies my mind :

how to support my family, and how to help you to support yourselves and

your children. While travelling this fall with the Governor-General and

Mr. Dewdney, I heard many things that have opened my eyes Very soon the

rations to the \ Indians will be stopped at Eagle Hills and other

Reserves; at least they will be greatly reduced, and Ave have only this

winter and next summer to receive help from the Government, so we will

have to mind ourselves and to work constantly, and make all the

preparations in our power for next spring. We must sow as much as we can

of wheat, barley, oats, potatoes, and every kind of vegetable. We must

take good care of our cattle, that they may prosper in our hands. We can

do a good deal of work with the help we get now from the Government; but

let us not forget it is the last year to receive rations. The

Governor-General told me so, and it will be so. Next summer, or, at the

latest, next fall, the railway will be close to us, the whites will fill

the country, and they will dictate to us as they please. It is useless

to dream that we can frighten them, that time has passed. Our only

resource is our work, our industry, our farms. The necessity of earning

our bread by the sweat of our brows does not discourage me. There is

only one thing that can discourage me. What is it? If we do not agree

among ourselves. Let us be like one man, and work will show quick, and

there will be nothing too hard. Allow me to ask you all to love one

another, that is not difficult. We have faced the balls of our enemies

more than once, and now we cannot bear a word from each other. Let the

women mind themselves, and not carry tales from one house to another. If

any persons carry stories to your houses, stop them at once. Tell them

that you do not get any richer or fatter by such nonsense, and the news

carrier will soon lose the bad habit. We have a missionary on our

Reserve, we have a school, let us profit by them. I have given you an

example. Nearly two years since I sent my son to Saint Albert, Big Lake

school. My heart was sick when I saw my boy crying at his departure from

me, and I find long the time of his absence, but he is at school. Some

day he will be able to help himself and to help his fellowmen. He will

be able to speak English and French, and he will be able to read and to

write, besides know how to work like a white man. Do the same for your

children if you want them to prosper and be happy."

Poundmaker had a

generous heart, and the lofty traits of his nature were written on his

handsome face. He was a savage statesman with an influence that reached

beyond his tribe. The clemency of the Government released the chief

before the expiration- of his term in prison. He was baptized and

admitted into the Roman Catholic church by Archbishop Tache while in

prison. After his release he went to the Blackfoot Indian Reserve to pay

a visit to Crowfoot, whom he still called father, in remembrance of the

youthful days when the Blackfoot Chief adopted him. Great, indeed, was

the rejoicing in the camp during his residence there. Suddenly, in

peaceful hours, the din of war no longer heard, and the prison days

ended, surrounded by friends of early days, he was stricken down. In the

midst of the festivities of the lodge he burst a blood vessel, and died.

Crowfoot mourned deeply for the loss of his adopted son. The Blackfeet

honored his memory, and the Crees heard with intense sorrow that the

heroic soul was 110 more. His name will always be associated with the

Rebellion in the North-West, but the nobler and truer side of his

character will best be known by his intimate relations with his people,

and his earnest struggles on their behalf.

HIAWATHA.

Longfellow's Indian

Edda has made familiar to a large circle of readers the famous exploits

of the native hero and reformer, Hiawatha. The substance of this

beautiful poem was founded on an Indian legend found in the works of

Schoolcraft, and incorporated with various native myths and customs and

descriptions of scenery in the land inhabited by the Ojibway tribes. The

poet was happy in his selection of an interesting subject, and of the

form in which the poem was cast. The metre, and many of the forms of

expression were suggested to Longfellow by the great Epic of Finland,

the "Kalevala" which reminds one of Homer's Iliad in the simplicity of

its lines, and the beautiful imagery of the poem. The "Kalevala" is a

description of the animal life of Finland, the manners and customs of

the early inhabitants, and is replete with the fascinating folklore

about the mysteries of nature. It consists of twenty-three thousand

lines, written in the sonorous and flexible tongue of Finland. Whether

or not it is the work of a single poet, or the-gathering together of all

the traditions of the country after they had been sung for ages by the

people, no one is able to tell. The fragments of the poem were collected

by two learned men, Topelius and Lonnrot, and published between 1822 and

1835. There are some striking parallelisms between the "KalevAla" and

"Hiawatha" in both incident and metre. In Hiawatha the Indians hope to

conquer a mighty fish called Misho-Nahma, a king of fishes, and in the "Kalevala,"

the hero Wainamoien, slays an immense pike, the water hound. Here are a

few lines in the original Finnish:

Kanteloista Kunlemahan

Soittoa tagumahan Pcnkaloitanza pesevi Oravat ojentilihe Lehvaselta

lehvasella.

A comparison between

the opening lines of the prelude of "Hiawatha" with the "Kalevala" will

show the resemblance in metre and sentiment. The opening lines of the

"Indian Edda" are:

Should you ask me,

whence these stories? Whence these legends and traditions? With the

odors of the forest, With the dew and damp of meadows, With the curling

smoke of wigwams, With the rushing of great rivers, With their frequent

repetitions, And their wild reverberations As of thunder in the

mountains?

I should answer, I

should tell you, "From the forests and the prairies, From the great

lakes of the Northland, From the land of the 0 jib ways, From the land

of the Dacotahs. From the mountains, moors, and fenlands, Where the

heron, the Shuh-shuh-gah, Feeds among the reeds and rushes, I repeat

them as I heard them From the lips of Nawadaha, The musician, the sweet

singer."

Should you ask where

Nawadaha Found these songs, so wild and wayward, Found these legends and

traditions, I should answer, I should tell you,

"In the birds' nests of

the forests, In the lodges of the beaver, In the hoof-prints of the

bison, In the eyrie of the eagle!

"All the wild fowl sang

them to him, In the moorlands and the fenlands, In the melancholy

marshes: Chetowaik, the plover, sang them, Mahng, the loon, the

wild-goose, Wawa, The blue heron, the Shuh-shuh-gah, And the grouse, the

Mushkodasa!"

The following, from the

"Epic of Finland," may be compared with the extract from Longfellow's

poem:

These are words in

childhood taught me, Songs preserved from distant ages; Legends, they

that once were taken From the belt of Wainamoinen, From the forge of

Ihnarinen, From the sword of Kaukomieli, From the bow of Youkahainen,

From the pastures of the Northland, From the meads of Kalevala; These my

dear old father sang me When at work with knife and hatchet; These my

tender mother taught me When she twirled the flying spindle. When a

child upon the matting By her feet I rolled and tumbled, Incantations

were not wanting Over Sampo and o'er Louki; Sami)^ growing old in

singing, Louki ceasing her enchantment, In^the songs died wise Wipunen,

At the games died Lemminkainen. There are many other legends,

Incantations that were taught me, That I found along the wayside,

Gathered in the fragrant copses, Blown me from the forest branches,

Culled among the plumes of pine-trees, Scented from the vines and

flowers, Whispered to me as I followed Flocks in land of honeyed

meadows, Over hillocks green and golden, After sable-haired Murikki, And

the many-coloured Kimmo.

Many rhymes the cold

has told me, Many lays the rain has brought me, Other songs the winds

have sung me : Many birds from many forests, Oft have sung me lays in

concord; Waves of sea and ocean billows, Music from the many waters,

Music from the whole creation, Oft have been my guide and master.

The legend of Hiawatha,

narrated by Longfellow, was taken chiefly from the writings of

Schoolcraft, and is a mass of mythical tales relating to native heroes.

In Schoolcraft's volume, entitled "The Hiawatha Legends," numerous

fanciful stories of the Ojibway hero, Manabozho, and his companions are

related, but not a single fact or fiction about Hiawatha. The legend was

given publicity by Mr. J. H. V. Clarke in his interesting "History of

Onondaga," wherein the original name of the hero is Taounyawatha, who is

described as the deity who presides over fisheries and hunting grounds.

Mythological tales have

become incorporated with the true story of this illustrious lawgiver and

reformer of the Iroquois, which lend an appearance of fiction to his

person and work. He is described as having descended to earth in a

snow-white canoe, and was seen as a demigod on Lake Ontario, approaching

the shore at Oswego. He reveals his divine origin to two Onondagas, who

become associates in his work, and maintain the great league of peace

after he has gone. He ascends the Oswego and Seneca rivers, removing

obstructions and making them navigable, and destroys all his enemies,

natural and preternatural. Afterward he lives peaceably among his people

as a man, and begins and carries forward his great work of establishing

the League of the Iroquois, and when his work is done, ascends to heaven

in his human form, seated in his white canoe, amid "the sweetest melody

of celestial music." Longfellow's "Hiawatha" is a myth without any

foundation. Still that does not destroy the fact that such a person as

Hiawatha lived, and executed a great work among the Iroquois. As the

Indians sat around their cabin fires in the winter, narrating stories of

the brave deeds of their forefathers, fact and fiction became blended,

and as they delighted in mysterious tales, the simple facts of a great

life became shrouded with the deeds of a god, and the wise man among his

people was elevated to the rank of a deity.

Hiawatha was a brave

and wise Onondaga chief, who loved peace and sought the welfare of his

people. His name signifies, " He who seeks the wampum belt." Beholding

the evils which befel his own and other tribes through incessant

warfare, he was greatly troubled, and revolving in his mind a means of

escape from the consequences of war, he set himself to the task of

uniting his own nation and enlisting them in a league of peace. He was

past middle life, and deeply respected for his wisdom and benevolence

among his people when he assumed the position of reformer and lawgiver.

As a chief of great influence, he summoned a council of the chiefs and

people of the Onondaga towns, and from all parts along the creeks, they

came together to the general council fire. Hiawatha had a redoubtable

foe in the person of an able chief, named Atotarho, who was strongly

opposed to his peaceful attitude, and gathering a number of reckless

spirits who belonged to his faction, he scattered them among the vast

concourse of people, so as to intimidate the chiefs, and the council

came to naught. A second council was summoned, but Atotarho was there

again with his foreboding countenance, and his followers were there

prepared to slay any who followed not the counsel of the grim chief, so

the council ended as the first, without anything being done. A third

council was called by Hiawatha, who sent out his runners in every

direction; but no one come, and the grave reformer was sad. Seated upon

the ground in sorrow, he enveloped his head in a mantle of skins, silent

in profound thought. At length he arose and departed from the homes of

his people, determined to enlist other tribes in the cause which lay

near to his heart. As he strode toward the forest he passed his great

antagonist seated near a well-known spring, but not a word passed

between them. Bent on his mission, he crossed mountains, and on the

shores of a lake which he crossed he found small white shells. He

gathered some of these and strung them on strings, which, he fastened on

his breast as an emblem of peace. These wampum strings were a,

significant token of his mission, and their use, apparently unknown to

the Indians before this time, although known to the Mound-Builders,

became symbolic to the natives of peaceful relations among the tribes.

He floated down the Mohawk River in a canoe. He arrived at a Canienga

town, whose chief was the famous Dekanawidah, and seating himself on a

fallen tree beside the spring where the 1 people came for water, he

remained silent. A woman came to draw water, but spoke not to him, his

appearance and attitude forbidding conversation ; but when she returned

to the house she said to Dekanawidah, "A man, or a figure like a man, is

seated by the spring, having his breast covered with strings of white

shells." The chief said to one of his brothers, "It is a guest, go and

bring him in, we will make him welcome."

Dekanawidah and

Hiawatha met, and the founders of the Oreat League took counsel

together, working out their plan and securing the consent of the people.

The matter was discussed in the council, and the Canienga nation decided

in favor of the scheme. Dekanawidah sent ambassadors to the Oneidas, who

were the nearest tribe to them, and the plan was laid before Odatsehte,

the chief, whose name signifies, the "Quiver-bearer." He required the

ambassadors to wait a year until he had discussed the question with his

council, and thought wisely over the matter. At the end of that period

the Oneidas became one I of the members, of the league. The Onondagas

were next appealed to, but the grim and haughty Atotarho still

remembered his contest with Hiawatha, and he refused the application of

the ambassadors. The Cayugas were entreated and their chief,

Akahenyouk,whose name signifies the "Wary Spy," readily obtained the

consent of his people, and united. The wisdom, eloquence and peaceful

policy of Hiawatha asserted themselves in again approaching the

Onondagas, despite the repulse of Atotarho. It was proposed to make the

Onondagas the leading tribe of the confederacy, their chief town the

place of meeting-for the league, where the records should be kept, and

Atotarho the principal chief, with the right to summon the league and

possessed of a veto power. The Onondagas were won, and Atotarho became

more zpalous for extending the league than he was formerly in opposing

it. Special prerogatives were granted the Onondagas, and Atotarho became

the Emperor of the Five Nations. The Seneca tribe was secured next, and

their two principal chiefs, Kanyadariyo, "Beautiful Lake," and Shade-karonges,

"The Equal Skies," were made military commanders of the confederacy. The

Ojibways became allies of the league; but after the space of two hundred

years, the alliance was broken through the influence of the French and

the sympathy of the Ojibways for the conquered Hurons. Other tribes were

appealed to by the ambassadors sent to them, urging them to become

members of the league, or allies, but without success. The great

council, composed of the representatives of the Indian tribes was a

federal assembly, and all questions brought forward for discussion were

first submitted to the tribal council, where they were settled by a

majority vote; but, in the federal council the vote must be unanimous,

and when this failed a plan of pacification was made, by which all

became agreed. Atotarho required not to exercise the veto, as he was

virtually governed by the wisdom of the members, who sought to follow

their policy of peace and maintain their unity. The laws which prevailed

in the league manifested the sagacity and statesmanship of Hiawatha. He

was made a chief of the Caniengas, and probably resided with that tribe

until his death. It is said that after the establishment of the Great

Peace, he devoted himself to clearing away the obstructions in the

rivers throughout the country inhabited by the tribes belonging to the

confederacy. At what time and in what manner he died is not known.

Numerous fabulous stories are related about him, some of which have

slight foundation in fact, and others are wholly fictitious. Mr. Clarke

relates the story of the marvellous bird which killed Hiawatha's only

daughter. When Hiawatha was in attendance at the great convention

summoned to form the league, he brought with him his only daughter, aged

twelve years. A loud rushing sound was heard, and a dark spot appeared

in the sky, when Hiawatha warned his child to await her doom at the

hands of the Great Spirit, and she bowed in resigned submission. The

dark spot became an immense bird, which swept down upon her with wide

extended wings and long beak and destroyed her.

Horatio Hale made

inquiries about this story among the Canadian Onondagas, and learned

that this was an actual occurrence, though somewhat modified. Before the

meeting; of the great convention, the Onondagas held a council in an

open plain, encircled by a forest, where temporary lodges had been

pitched for the councillors and their attendants. Hiawatha was there,

accompanied by his daughter, who was married, but was still living with

her father. At the close of the discussions, which lasted until night,

and as the people were in the lodges, the women were returning from the

forest laden with fuel for cooking purposes, and among them was the

daughter of Hiawatha. As she moved slowly with her burden the loud voice

of Atotarho was heard, shouting that a strange bird was in the air, and

bidding one of his archers shoot it. The bird was killed, and the people

rushed toward the spot, and in the excitement Hiawatha's daughter was

crushed to death. Atotarho had no doubt planned this onset and this sad

calamity, to harrass his adversary, and in the intense grief which

filled the heart of Hiawatha he found delight.

The Iroquois extol the

wisdom, eloquence and great virtues of Hiawatha, and hold him in

reverence, believing firmly that he was the founder of their league. The

name of Hiawatha is borne at the present day by some of the farmer folk

on the Grand River Reservation. Horatio Hale has made a thorough

investigation of the facts relating to the league and its founder, and

has come to the conclusion that Hiawatha was a historical personage, a

grave lawgiver and reformer, and that the legend is composed of false

and true elements which must be separated so as to be understood. Dr.

Brinton says that the legend is a myth, a preposterous tale, based on

early traditions, and Dr. Beauchamp as strongly asserts that it is a

modified life of Christ. There is no doubt the influence of the teaching

of missionaries has changed the form of the legend, which is not related

by the aged men of the tribes with uniformity, and as the traditions of

the natives are undergoing a process of transformation through contact

with the white man, it is impossible for them to keep intact the stories

told in the lodges. Thus we have the strange bird which the archers of

Atotarho slew, when Hiawatha's, daughter was trampled to death,

represented as a white bird, having the form of a cross; and Hiawatha,

stricken with grief, is said to have lain as one dead for three days.

Afterward he arose to life, formed the League of Peace, appointed its

officers, and after setting everything in order, resumed his divinity,

and ascended to heaven in a white canoe. These are features which

suggest the influence of Christian teaching.

Divested, however, of

these accretions of Christianity, and of the supernatural elements which

have been introduced by the story tellers of the lodges, Hiawatha

appears as a wise man, a, human being of more than ordinary ability, who

began an era, of peace among the Indian tribes. The artist has found

subjects for his pencil in the legend. The meeting of Atotarho,

Dekanawidah and Odatsehte, is the subject of a rude pictorial

representation, supposed to be the work of David Cusick, the historian

of the Six Nations. Atotarho, "The Entangled," is seated, grim, solitary

and dignified, smoking a long pipe, his head and body-enveloped with

angry and writhing serpents. Before him stands Dekanawidah, as a plumed

warrior, holding in his right, hand his flint-headed spear, as the

representative of the Caniengas, or "People of the Flint." Beside him

stands Odatsehte, bearing in his hand a bow with arrows, and a quiver at

his shoulder. Dekanawidah is addressing Atotarho on the founding of the

league, and the surly Onondaga chief, who is. listening to the project,

reveals in his aspect his attitude toward the scheme of Hiawatha, and in

his dress his warlike character.

It is a

semi-mythological picture, indicating the love of the natives for the

mysterious. Edmonia Lewis, the sculptor, whose father was a negro, and

her mother, an Ojibway Indian, spent her early years modelling beads and

wampum, until she produced her two best works in marble, "Hiawatha's

Wooing" and "Hiawatha's Wedding."

Hiawatha's design of a

universal federation of his race was worthy of a master mind. The misery

of war had probably wrought so powerfully on the minds of the natives

that the future was foreboding, as predicting the extermination of the

race. This Iroquois lawgiver originated the plan of a reign of peace,

supported by a federation of all the tribes. Although the work of

Hiawatha did not become universal, the Confederacy of the Six Nations,

and the native government, as shown by the laws of the league, revealed

the genius of the man. As a native statesman, an undaunted reformer, an

eloquent speaker and a man of virtue, he is esteemed by the Iroquois.

Though we may grieve over the loss of the historical Hiawatha in

Longfellow's beautiful poem, we can admire and honor goodness and

ability wherever found. Among the red men there has not appeared a

greater teacher and a wiser man than Hiawatha. Such a character living

four centuries ago, the reputed founder of a new era, would naturally

have many strange tales told concerning him and his work, and it is

because of his greatness and the age in which he lived that so many

strange things are spoken about him. His name and brave deeds are

preserved in the traditions of the Iroquois, his memory is revered in

the "Book of Rites," his work remains in the league which he

established, and his influence abides in the life of the people.

SHAWUNDAIS

Shawundais was a

Mississaga Indian. The Mississagas are a sub-tribe of the Ojibways, and

are supposed to be the descendants of the Ojibways who defeated the

Iroquois in 1759. They are located at the New Credit settlement, near

the city of Brantford, Alnwick, Chemoug Lake, Rice Lake and Scugog.

Shawundais was known to

the English-speaking people as John Sunday, a famous missionary, who

frequently appeared on the public platform throughout Ontario,

delighting large and deeply-interested audiences with his quaint

speeches and thrilling records of missionary adventures. He was born in

the State of New York about the year 1796. His boyhood was spent in the

Indian camps. The natives travelled in those days along the courses of

the rivers and through the forests, gaining a precarious livelihood,

their camps infested frequently with white men of the lowest type, and

the men and women debauched with liquor and loose morals. They were an

industrious community until the white men introduced whiskey among them,

which made them idle and dissolute. In their industrious years the men

roamed the forests for game, the meat was retained for food, and the

furs sold to procure the lesser luxuries of life. Sugar making in the

woods in the spring was a busy season, and when that was over they were

ready to engage in the delightful occupation of fishing. They built

canoes, which were so light that two men could carry the largest of

them, and yet they were so strong that they could surmount the heaviest

billows and suffer no harm. The childhood days of Shawundais were spent

in the filthy camps of the natives, so sadly changed by the detestable

fire-water from the cleanliness and scenes of industry of former years.

The wild revelry of drunken men and the yells of debauched women filled

the midnight air. The children were neglected during these scenes of

delirium, and numerous tales of suffering were told in those days of

sadness and sin. The parents of Shawundais were pagans, his companions

were ignorant and degraded, and there was no man to reach forth a

helping hand or speak an inspiring word to lead the youth toward

self-improvement and civilization. Frequently he accompanied the Indians

in their begging dances to the settlements of the white people. He

attended their dog feasts, made sacrifices to the sun, and prayed that

no evil might befal him. He belonged to the band known as the Bay of

Quinte Indians, who roamed from the County of Northumberland to Leeds,

making Kingston, Bath and Brockville their chief places of resort.

Shawundais, the name of

our subject, means "Sultry Heat," which the sun gives out in summer just

before a fertilizing rain. He was rather above medium height in manhood,

and his physical frame was strong and well knit. In personal appearance

he was unprepossessing ; a simple child of the forest, trained in native

lore, familiar with the birds, flowers and insects, and without anything

striking in physique or intellect to arrest the stranger. He was,

however, a savage mimic, and his fund of ludicrous stories seemed

inexhaustible. Oftentimes groups of red and white men gathered around

him to listen to his humorous tales, and every member of the circle was

soon thrown into fits of laughter. In his early years he was a

successful hunter and a drunkard. Naturally quiet and inoffensive, when

the fire of his anger was kindled it became a roaring flame, which

burned all who dared to approach. His powers as a wit won the applause

of his companions and white neighbors, and this satisfied him. There

were serious moments, however, in his lodge when alone, and thoughts of

God and eternity filled his mind. Then would he say to himself, " Who

made the trees and animals, and stars above, and what sort of a being is

He ? How did man come into being? What will be his destiny when he

leaves this world !" He fasted and prayed, blackened his face, and

waited for a vision which would disclose to him some object in nature as

his personal deity. He was unhappy, yet the tears came not to bring

relief to his mind.

About this time the

Ojibways were brought under Christian influences, through the efficient

labors of the Rev. William Case, who devoted many years in missionary

work among the Indians of the Province of Ontario. In February, Mr.

Case, accompanied by a young Mississaga Indian—subsequently well known

throughout the Dominion—Peter Jones, started on a missionary tour to the

Bay of Quinte Indians. A public service was held in the church at

Belleville, which was well attended by the white people and Indians.

Shawundais had heard about the missionaries, and was anxious to learn

for himself some of the strange things which they related in their

message to the people. Accompanied by an Indian named Moses, he started

for Belleville and, upon arriving at the church, found it so crowded

that it was impossible for him to enter. During the mdrning service the

two Indians sat outside; but, at the hour for the evening service, they

were determined to hear for themselves the story the missionaries had to

tell, and they made their way into the church. Peter Jones addressed the

Indian part of the congregation upon the two ways of life—a favorite

topic with native preachers, and one which the natives appreciate. As he

described the way leading to destruction and the path leading to life

the heart of Shawundais was smitten, and he resolved to try to serve the

God of the Christians. So deeply was he impressed, that the thoughts of

the young Mississaga's discourse never left his mind. A second

missionary visit was made and, at a prayer meeting held on May 27th,

1826, a large number of Indians prayed, and told in simple yet eloquent

language of the great blessings they had received. Several young persons

said, with tears in their eyes: " We are going to serve the Great

Spirit, because we love Him with all our hearts;" and the penitent then

found the peace he sought. Shawundais was unable to read or write, but

his abilities were sufficient to induce him to be sent to school, with

the hope that he might be trained for missionary work among the natives.

His education was limited; but after he had learned to read and write,

he wrote a quaint account of his conversion, Which has been preserved.

Several years after his

conversion he related, in forcible language, the story of his entrance

into the peaceful way of God. At a camp meeting, held on Snake Island

about two years after his conversion, he gave several striking

addresses, clothed in the phraseology of nature and grace. Speaking of

his life as a pagan, and his subsequent experience as a Christian, he

said that Christians ought to be as wise as the red squirrel, who looks

ahead, thinking of the approaching winter, and provides food for every

contingency. They ought to imitate the red squirrel by preparing to meet

God. Now is the time to lay up the good words of the Great Spirit. Where

will he go who refuses to be as wise as the red squirrel ? At the same

meeting he related his own experience, saying, "My brothers and sisters,

I have been one of the most miserable creatures on earth. I lived and

wandered amongst the white people on the Bay of Quinte, and contracted

all their vices, and soon became very wicked. At one time I had a

beloved child, who was very ill. I tried to save the child from dying,

but could not, as the child died in defiance of all that I could do for

him. I was then more fully convinced that there must be some being

greater than man, and that the Great Being does all things according to

His own will. When I heard the missionaries preach Jesus Christ, and

what we ought to do to be saved, I believed their word, and I began at

once to do as they advised, and soon found peace to my soul. Brothers

and sisters, I will tell you what the good missionaries are like— they

are like sun-glasses, which scatter light and heat wherever they are

held ; so do the ministers of Christ spread the light of truth amongst

the people, which warms their hearts and makes them very happy."

Possessed of a lively

imagination, apt to describe men and things in an impressive manner, his

short period of training enabled him to address large audiences with

pleasure and profit.. He lacked the dignity of the ideal Indian, and the

stately eloquence of the native orator belonged not to him, yet there

was an irresistible charm about his speeches, with their quaint

illustrations, which won the hearts of his hearers. Within two months,

after his conversion he was impelled by love for the souls of men to

accompany Peter Jones on a missionary tour, relating the story of his

life and conversion. Early one morning William Case was awakened by

sounds from a wigwam, evidently of a person in deep distress, and

proceeding to the wigwam he observed an aged woman addressing some

people with intense earnestness. Upon inquiry, he learned who she was,

as Shawundais gladly said, "Oh! it is my mother. She so happy all night

she can't sleep." Encouraged by such tokens of success in his labors, he

prosecuted his work with greater zeal.

The temporal welfare of

his people deeply interested him, and he sought to help them to become

civilized like the white people. He was a member of a deputation of

chiefs from the Ojibways who interviewed the Government on matters

relating to timber and land. He told the civil authorities that a great

work had been done among his people, whereby they were forsaking their

pagan rites and superstitious ideas, and progress was being made among

them in material things. Along the north shore of Lake Huron he visited

several Indian camps, preaching the Gospel to the people.

In 1828 he visited New

York, Philadelphia, and other places in the United States in the

interests of the missionary work among the natives of Canada. In Duane

Street Methodist Church, New York, he delivered a characteristic address

in his own language which aroused the enthusiasm of the congregation.

His pathetic appeals, deep sincerity and vivid gestures revealed the

thrilling eloquence of the speaker, and although the language was

unknown to the audience, many persons were bathed in tears. When Dr.

Bangs addressed him through an interpreter, giving him, in the name of

the congregation, the right hand of fellowship, and expressing the hope

that they would all meet in heaven, the faithful Shawundais cried,

"Amen," as the tears flowed down his cheeks, and the congregation

mingled their tears with his, as they gazed upon the savage won from

superstition and vice. When he returned to Canada he told his people of

the religious institutions he had seen. The noble-hearted men and women

he had met, and their manifestations of sympathy and deep interest in

him personally, and in the tribes in the Dominion.

Shawundais became an

eloquent preacher to his own people, silence reigned when he addressed

them, the coldest hearts were touched, and many of the dusky worshippers

wept and prayed; scoffers remained to pray. His sermons and addresses

made lasting impressions on many hearts. Several times he visited the

Indians at Penetanguishene and Sault Ste. Marie, and his labors among

the red men were crowned with success. He gave an account of one of

these missionary tours to Peter Jones: "After you left us at Matchedash

Bay, we came to five Indian -camps, a few miles north of Penetanguishene.

Here we stopped three days and talked to them about Jesus Christ, the

Saviour of the poor Indian. Some of the young Indians listened to our

words, but others mocked. Among this people we saw one old man who had

attended the camp meeting at Snake Island last year. This man told us

that he had prayed ever since that camp meeting, 'But,' said he, 'I have

been compelled by my native brethren to drink the fire-water. I refused

to take it for a long time, and when they would urge me to take the cup

to drink I would pour the bad stuff in my bosom until my shirt was wet

with it. I deceived them in this way for some time, but when they saw

that I did not get drunk they mistrusted me, and found it out, so I was

obliged to drink with them. I am now sorry for the great evil that I

have done. Some of the young people said that they would like to be

Christians and worship the Great Spirit, but their old people forbade

them. These young people were very anxious to learn to read and sing.

Thomas Biggs, my companion, tried to teach them the alphabet. When we

would sing and pray, they would join in with us, and knelt down by our

sides; but the parents of the young people were very angry at their

children for praying, and one woman came and snatched a blanket from her

child that was kneeling down, and said, 'I will let you know that you

shall not become a Christian unless first bidden so to do by the old

Indians.' After spending three days with these people we went on to the

north on the waters of Lake Huron, as far as Koopahoonahning, but we

found no Indians at this place, they were all gone to receive their

presents at the Island of St. Joseph. We were gone two weeks, and having

got out of bread and meat, we were obliged to gather moss, called in the

Indian tongue, wahkoonun, 'from the rocks.' This moss we boiled, which

became very slimy, but which possessed some nourishing qualities. On

this we lived for several days together, with now and then a fish that

we caught in the lake. After returning to' the Matchedash Bay we saw the

same Indians that we spent the three days with at Penetanguishene. We

talked to them about religion. They answered, 'That they were looking at

the Christian Indians and thinking about their worship. When we are

convinced that they do really worship the Good Spirit and not the bad

spirit, then we shall worship with them and travel together.'

"At Penetanguishene we

saw about thirty Indians from Koopahoonahning, where we went, and then

returned from our visit to the north. We told these people the words of

the Great Spirit, and they said ' that they were glad to hear what the

Great Spirit had said to His people; if we were to hear more about these

things, maybe we would become Christians, too, and worship with you.' We

saw one old man at Matche-dash with Brother John Asance's people, who

has been much afraid of the Christian Indians, and has been fleeing from

them as his greatest enemy, and kept himself hid so that 110 Christian

Indian could talk with him. This man continued hiding and running from

praying Indians until he got lame in both of his hips, so that he could

not run or walk, and was obliged to call to the Christian natives to

help him. He now sees his folly, confesses his errors, prays to the

Great Spirit to have mercy upon him, and has become tamed and in his

right mind. We also visited the Roman Catholic Indians, who have lately

come from Drummond's Island. We told them what the Great Spirit had done

for us, and how happy we were in our hearts in worshipping the Great

Spirit who had saved 11s from drunkenness and from all our sins. They

said that they would like to see and hear fen* themselves how we

worshipped the Lord. So they sent those that came with us to this

meeting, that they might go and tell their brethren just how it was, as

a great many bad things had been told them about our way of worship by

the French people among them. This is all I can tell you of our travels

and labors among our native brethren in the woods."

In 1832 he was

appointed by the Conference missionary to the Sault Ste. Maris and other

bodies of natives. He roamed the woods in search of Indian camps to

preach to the natives and among the number of those who became converts

to the faith were some of the chiefs and medicine men, who laid aside

their medicine bags and ceased their incantations. On the south shore of

Lake Superior he visited the Ojibways, and declared the truth with such

earnestness that they forsook their native religion. In 1834 he was

ordained and settled as missionary to the Indians on Grape Island; but

his missionary zeal compelled him to seek other bands of natives beyond

his own Mission. So excessive were his labors that his strong

constitution was undermined, and he was induced to visit England. He

travelled extensively in England pleading the cause of Missions during

the year 1837, and large audiences gazed in astonishment upon him, and

were enraptured with his quaint addresses. He was presented to the Queen

as the chief of his people, who had authorized him to act on their

behalf. After his return he visited the Indians at Sault Ste. Marie, and

from 1839 to 1850 he labored among his people at Rice Lake, Mud Lake and

Alderville. At missionary meetings in Canada and the United States,

among red men and white, he preached and lectured, and so wide was his

field of operations that he quaintly said, "My family lives at

Alderville, but I live everywhere."

After spending four

years among the Indians at Mount Elgin and Muncey, he labored for eleven

years at Alnwick, and then, in 1867, he was superannuated, spending the

remaining years of his life at Alderville. His last days were filled

with labor, and as oftentimes he referred to the old days of paganism,

he urged his brethren to be faithful to the cause which lay so near to

his heart.

At the advanced age of

eighty years he died, amid the sympathy and honor of all the people. He

died at Alderville on December 14, 1875. Heroic in the discharge of his

duties, he was the champion of the rights of his people.

As an advocate of the

cause of missions his memory still lingers. At a missionary meeting held

at Hamilton, Ontario, in closing his address he gave his " Gold Speech,"

as follows:

"There is a gentleman