|

THE territory now

included in the Province of Manitoba, is essentially agricultural in

character. A study of the physical features of the country presents many

peculiarities indicating its fitness for the production of crops.

Topographically, the

Province may be divided into two separate plains or steppes. The first

of these extends from the Eastern boundary westward to a ridge known in

different regions as Pembina Mountain, Riding and Duck Mountains, and

Porcupine Hills. This plain was originally a great lake which gradually

receded from its former shores to what is now Lake Winnipeg, leaving

Lake Manitoba and a few smaller bodies of water as basins for the

drainage from the old lake bed. It is a fertile stretch with a marly

clay sub-soil, and a black alluvial surface, the darkness of colour

being due, in the opinion of Dr. Dawson, to the frequent burning of

grass.

In describing Manitoba,

J. Macoun, Dominion Geologist, says:—“High above the Pembina Mountains

the steppes and plateaux of the Riding and Duck Mountains rise in well

defined succession with southern and western steppes; of these ranges

the terraces are distinctly defined, and the north-east and north sides

present a precipitous escarpment which is elevated fully 1,000 feet

above Lake Winnipegosis, and more than 1,600 feet above sea level. ’'

When viewed from the

south and east the Riding Mountains present a peculiar aspect. Close to

the ridge, the surface is marshy in many places, but, there are visible,

three distinct steppes separated from each other by plateaux of

considerable extent. Standing on the edge of the escarpment and looking

in the direction of Lake Dauphin, a gulf two or three miles wide and 250

feet deep, are to be seen two ranges of cone-shaped hills, one lower

than the other and covered with boulders. These are parallel to the

general trend of the escarpment. In some places, they are lost in the

plateaux on which they rest; in others they stand out as bold eminences

showing the extent of the denudation which gave rise to them. These

conical hills correspond to the terraces on the south-west side of the

Mountains.

Next in the series come

what are known as the Duck Mountains, a high range of tablelands

similar, in many respects to the Riding Mountains. This range is

entirely cut off from the Porcupine Hills, by the Swan River, which

flows in a deep valley between the two ranges; and, on the west from the

Great Western prairie, by the Assiniboine River. Proceeding eastwards,

these mountains are mostly gently rolling elevations, but, in a few

instances, take the form of cone-shaped hills. Where not covered with

timber, they are overgrown with a luxuriant and almost impenetrable

growth of peas and vetches. From the north-eastern side of the

escarpment Lake Winnipegosis is plainly visible A,#00 feet below.

Between the north-eastern slope of the Duck Mountains and Lake

Winnipegosis, the land in some places is wet and marshy, and will

require drainage before it can be successfully cultivated.

The northern portion of

the Province, east of the mountain range, is covered, to a large extent,

with wood timber. The wooded area commences in the southeastern portion

of the Province and continues in a line running north-west, striking

first the southern point of Lake Winnipeg, then cutting Lake Manitoba

about the centre, touching the Riding Mountains at their most southerly

point and following north along the western boundary of the Duck

Mountains and Porcupine Hills. North of this line the prairie is wooded,

and all south of it is bare, with but slight exceptions.

Large areas of the

north centre, between Lakes Winnipeg and Manitoba, are interspread with

beaver mead cows, some of which are of considerable size, reaching from

1,200 to 1,400 acres. Midway between Lakes Winnipeg and Manitoba nearly

all the creeks have been dammed by beavers for the purpose of

constructing their abodes. These dams have been found to make good wagon

roads, and are often used for this purpose by settlers and others. If

the dams were cut through the meadows would be naturally drained. Many

of these are already dry enough to make good hay lands for settlers.

That portion of

Manitoba known as the Red River Valley, extends from the eastern

boundary of the Province westward to the Pembina Mountains, a ridge

which, at one time, formed the western shore line of the great lake

already referred to. The summit of these hills is level for a distance

of about five miles, till the foot of another terrace is reached. The

summit of the second terrace is level with the Great Buffalo Plains,

that stretch westward beyond the Manitoba boundary, and form a fertile

tract, once the hunting ground of the Indian, but now the home of

thousands of prosperous farmers. Close to the east of the ridge the land

is marshy, and this circumstance has in some instances interfered with

settlement.

Much of the central and

northern parts of Manitoba present a limestone formation, indicated in

these regions by out-croppings of large limestone slabs. There are also

large belts of loose, irregular rocks, which are often found so close to

the surface as to constitute a serious hindrance to cultivation. The

early settlers in Manitoba soon found that the land was admirably suited

for the purposes of agriculture. In the Red River Valley, the soil close

to the river was found to contain a very high percentage of fine clay,

and, although heavy to cultivate, proved to be very fertile. Passing

from the river on either side, the soil was found to be more friable. In

the north and west beyond the first ridge, the plain, in most places,

consisted of a sandy or light clayey loam, capable of cultivation early

in the springtime and suitable for the production of crops in a minimum

amount of time. Although this region was more northerly than any which

had been successfully cultivated in North America, it was found to be

eminently productive. Manitoba has approximately twenty-four million

acres suitable for agricultural purposes, and about one-fifth of this

has so far been brought under cultivation. Owing to the ease with which

the prairie land can be broken and cropped, the new settler very quickly

makes a home for himself, and often, within eighteen months, has a

surplus of grain to dispose of. A hundred years ago the territory now

included in the Province of Manitoba was the home of thousands of

buffalo. Until the advent of the Canadian Pacific Railway, comparatively

few settlers found their way into this country. Those who came had no

inducement to grow more than would supply the home market.

The first attempts at

farming in the Province were made by the Selkirk settlers, in 1816. This

colony numbered two hundred and seventy people, who were chiefly Scotch,

sent out by Lord Selkirk, but, later, the settlement included some

Irish, French and Swiss. These were intended to colonize the one hundred

and ten thousand square miles of land granted to Lord Selkirk, by the

Hudson’s Bay Co. Each of the settlers bought one hundred acres for which

he agreed to pay one dollar and twenty-five cents per acre. The farms

were from six to ten chains wide and ran back from the river front about

two miles, and were hence often referred to as "lanes." This kind of

subdivision, however, had its advantages; the river, which was the

principal highway, was close to all settlers, and enabled them to secure

an abundant supply of water and fish. This system of survey also made

the settlement more compact, and hence was safer in times of danger. The

settlers congregated around Fort Douglas, sowed in the spring of 1816 a

few bushels of wheat and barley, and planted a few pecks of potatoes.

From this first crop the returns were excellent, wheat yielding 40,

barley 50, and potatoes 100 fold. The grain was cut with a sickle or

cradle and was threshed with a flail, and the "Quern" or hand stone was

used to crush the grain into flour. In 1817, the settlement was called

Kildonan, after the native parish of the Scotch settlers. From 1818 to

1821, the crops were more or less destroyed by grasshoppers, and in

1820, there was no seed grain whatever in the settlement. In February,

1821, a party was formed to bring 250 bushels of wheat from Prairie du

Cluen, in the United States. This grain cost 82.50 a bushel at the place

of purchase, but yielded well in the fall of 1821, and was all kept for

seed the next year. The first importation of cattle took place from the

United States, in 1822, when the prices paid were $150 for a milch cow,

and $90 for an ox. A few ploughs were in use in 1823, but most of the

settlers still used the hoe and spade. About this time the two-horse

tread-mill for grinding wheat was introduced, followed later by a Hudson

Bay windmill, at Fort Douglas. A slight check was given to agriculture

by the flood of 1820, but the supply of grain soon exceeded the demand,

and a large stock was left over each year. The Hudson’s Bay Company

could purchase only eight bushels of wheat from each farmer, and four

bushels from “trip” men, the price paid being S7 cents per bushel. The

settlers, however, were able to raise, even with their primitive

implements, ten times as much as they could sell.

In 1816, Lord Selkirk

endeavored to assist the settlers by establishing an Experimental Farm,

his ambition being to improve the breeds of cattle and horses, and to

increase the yield of grain and dairy products. The Hudson’s Bay Company

also started an Experimental Farm about 1830, near Upper Fort Garry.

Good buildings were erected and animals of the best breeds were

imported, among them being a fine stallion from England, at a cost of

$1,500, and also a number of mares. These excellent animals greatly

improved the breed of horses in the settlement. In 1832, a company was

formed for the purpose of breeding large herds of cattle, for the sake

of their hides and tallow, but owing to bad management, the enterprise

failed. A few years later efforts were made to grow flax and hemp on a

large scale, but, although these grew well, labor was too scarce to make

the venture profitable. According to the census of 1849, the live stock

in the country had increased to nearly 13,000, and over 6,000 acres were

under cultivation. After the first Riel rebellion, settlers came pouring

into the country and the acreage under cultivation increased rapidly. It

is difficult at this distance of time to speak positively in regard to

the first varieties of wheat used but thirty-five years ago there were

two varieties in cultivation—an early stiff-bearded variety not very

productive, and a beardless kind having a hard red kernel, rather longer

than Red Fyfe, and apparently of good milling value. The last mentioned

was grown on the Brandon Experimental Farm for some years under the name

of the "Old Red River Wheat."

About 1877, the Golden

Drop Wheat was grown extensively by some of the best farmers. This was a

very fair wheat but somewhat soft, and inclined to smut badly. About

1880, the famous Red Fyfe Wheat was introduced into the West, a variety

supposed to have originated on the Baltic coast. It is very productive,

has a healthy, vigorous plant, the berry being hard and bright, the bran

thin, and the gluten contents high, making its milling qualities

unequalled. This variety has done more to keep up the reputation of the

Province as a wheat-producing country than any other, and the greater

proportion of the wheat exported is of this sort

On the establishment of

the Dominion Experimental Farm in this Province, in 1888, an effort was

made to introduce new varieties of early ripening wheat for sowing in

the more northern parts of the country. The first to be tested was

imported from northern Russia, and was called Ladoga. This was an early

variety, but the quality was not equal to the requirements of the

country. Later, Dr. Wm. Saunders, Director of the Experimental Farms,

introduced several cross-bred wheats, such as the Preston and Stanley.

These have been grown with more or less success in the less favoured

parts of the country, but are not to be recommended in preference to the

Red Fyfe, where that variety can be ripened successfully.

The acreage sown with

barley in Manitoba is increasing very rapidly. Within six years the area

occupied by this useful grain has doubled. The results of many years ’

experience show that the Chevalier varieties of two-rowed barley have

not succeeded well. The ear seldom fills perfectly, and every year these

varieties are more or less lodged, and they are late in maturing. The

two-rowed sorts of the Duck-Bill type, such as Canadian Thorpe, are much

stiffer in the straw, and generally speaking, the heads fill well. The

six-rowed varieties are those best adapted for general cultivation. They

ripen early and can be sown later than other grain, and even then will

mature early enough to escape injury from autumn frosts. The straw is

nearly always stiff and bright, and the ears well filled. Of these

varieties the Mensury and Odessa are excellent. The average yield of

Mensury barley on the Brandon Experimental Farm, for the five years

ending 1907, was 63 bushels and 40 pounds per acre. Odessa gave an

average return of 64 bushels and 40 pounds per acre for th< same period.

Barley is largely grown

as a cleansing crop. The method is to spread barnyard manure on the

stubble in spring, ploughing it under and sowing about the end of May.

This practice gives a good crop and the land is left comparatively clean

and ready for wheat the following year.

The yield of oats is

usually very satisfactory throughout the Province, when proper care is

given to their production. Although not so important as wheat, the sale

of this grain for oatmeal and feeding purposes is increasing each year,

and the price obtained is higher than in former years. A fairly pure and

clean sample of heavy Manitoba oats is looked upon with much favor by

oatmeal millers throughout the Dominion, and finds sale at remunerative

prices. In some districts of this Province, where the soil is better

adapted for oats than for wheat, that grain is grown almost exclusively.

By careful selection of seed, and thorough cultivation, lm mense yields

are obtained, and many farmers report an average of eighty bushels per

acre over their entire farms. The “Banner” oat has been the favourite

for a number of years This is a thin, hulled sort, of excellent quality,

and very productive. Other valuable varieties are "Abundance," "Ligowa"

and "Newmarket." These are all white oats, and sell at a good figure for

milling purposes. The place occupied by oats in the rotation of crops is

usually after wheat and just previous to either a barley crop or summer

fallow. For this reason the returns per acre are not as large as they

otherwise would be. On the Experimental Farm at Brandon, on summer

fallowed land, without fertilizer, the average yield of “Banner” oats

for the five years ending 1907, was 116 bushels and 4 pounds per acre.

This is an indication of what can be accomplished on our rich soils with

good cultivation.

In the newer

settlements there is an abundant supply of natural hay on the lower

lands and water meadows. For some years, this supply will be sufficient

for all demands. Later, when these lands are drained and turned into

grain fields, the farmer will be compelled to look elsewhere for his

supply of hay.

Fortunately there are

many varieties of cultivated grasses and other fodder plants, that give

profitable yields in this country. The most popular grass is “Timothy;”

this excellent grass is grown most extensively on the more moist soils

of the Province, and returns on such soils are exceedingly good. Where

“Timothy" fails to give large returns, Western Rye grass is grown with

profit. This is an excellent native grass and is now extensively

cultivated. In other districts where the soil is light "Austrian Brorne"

is grown with good results. Among the annual fodder plants the following

are cultivated with success:—German, Japanese and Common Millet, Broom,

Com and Hungarian grass ; these all give excellent returns of useful

hay. Although Indian com is not grown for the grain, it is a decided

success here as a fodder plant. When sown about the middle of May it

grows rapidly during our long bright days, and soon reaches a height of

from 8 to 10 feet, the yield often amounting to from 15 to 20 tons of

green fodder per acre. This is either made into

ensilage or stooked in

the fields until required for feeding. Whether used as fodder or

ensilage it is excellent for fattening cattle, and is one of the very

best foods for milch cows.

In all parts of the

Province where the original prairie sod is thick and tough, it is

customary to “break and back-set,” but where the land is covered with

small trees and scrub, breaking and back-setting is not necessary. 'I he

breaking of new prairie is best accomplished with the hand breaking

plough, having a rolling coulter, but fairly good work can be done with

a sulky plough if the land be very smooth and level. For the best

results the breaking should be shallow, and the work completed by July

1st. A few weeks after breaking the sod will be rotted and the land

should then be "backset." This is carried out by ploughing in the same

direction about two inches deeper then previously, thereby bringing up

some additional soil for a seed-bed. After "back-setting" the land must

be made as fine as possible with a disc-harrow or some other similar

implement. If this plan be adopted only a light harrowing will be

required when the land becomes seeded in the following spring. In some

parts of the Province, the land is too rough to permit of thin breaking.

In such districts, the land should be ploughed from 4 to 5 inches deeper

than in the smoother lands, and as early as possible in the year. It

should also be well harrowed in order to level the surface. In such

cases a second ploughing is not necessary, but the ground must be again

harrowed the following spring, before the grain is sown.

A considerable portion

of the best land in Manitoba is covered with small timber and scrub

which, when cleared, produces magnificent yields of all kinds of farm

produce, and the work of clearing is very light when compared with that

of preparing the heavy timbered land of other countries. The method of

clearing such lands is just to chop out the larger poplars and willows

during the winter. A fire is then run over the land in order to bum the

remaining portion of the scrub. After this the ground may easily be

broken with a strong brush plough; all the additional levelling can be

accomplished with a disc-harrow or other similar implement. The land is

then ready for seeding, and usually yields large returns. Immense areas

of this class of land are still open for settlement, principally in the

northern part of the Province, and can be obtained either as free

homesteads or for a nominal price.

The larger proportion

of the wheat crop of Manitoba is grown on land that has produced a grain

crop of some kind the previous year. The stubble land is ploughed in the

autumn as early as possible; the land is then harrowed and sown in the

following spring. This system is very inexpensive, and, when the land is

new and the seasons favourable, the profits are large and immediate. But

this exhaustive plan cannot be retained for any great length of time.

Sooner or later a regular system of rotation has to be adopted. A common

practice is to include a season’s summer fallow in the rotation, and the

most approved plan for this operation is to plough the grain stubble in

June, just as soon as the weed seeds have begun to germinate. The soil

is then “compacted” with either a “sub-surface packer” or other similar

implement, and this proceeding is followed by thorough surface tillage

during the summer, in order to kill weeds and prevent evaporation of

soil moisture.

Summer fallowing is

practiced in Manitoba by most farmers, its frequency depending on the

character of the soil and other conditions. Some of the largest and best

crops of wheat are obtained after this treatment, and the condition of

the soil is greatly improved at the same time During recent years the

more advanced farmers have included the culture of grass in the

rotation. The

usual practice is to

sow either Timothy or Western Rye grass with a “nurse crop;” to cut it

for hay during the two following seasons, then to pasture for the third.

This plan furnishes both hay and pasture for the farm, gives the land

certain rest and so fills the surface with root fibre that soil drifting

is prevented. At one time it was thought that none of the clovers would

thrive in Manitoba, but, by practicing improved methods of cultivation,

all the perennial and biennial species are found to be just as hardy and

productive as in the eastern provinces. The fact that these leguminous

crops can be grown suggests great possibilities for the agriculture of

the West. To prove successful on the majority of farms in this country,

clover of all kinds should be sown without a “nurse crop” of grain,

although, in very favorable seasons, a very light seeding of grain may

be permissible if cut early for green feed. In growing red clover

excellent results have been obtained by ploughing gram stubble in

spring, harrowing once, then sowing about 12 pounds of clover seed per

acre, harrowing a second time and rolling. When the weeds and “volunteer

crop" of grain are about a foot high, a mower should be run over the

land and the cuttings left on the ground to act as a mulch. By this plan

the clover plants become large and well rooted before autumn, and there

is no danger of winter killing. Two cuttings of clover can be gathered

in the following year.

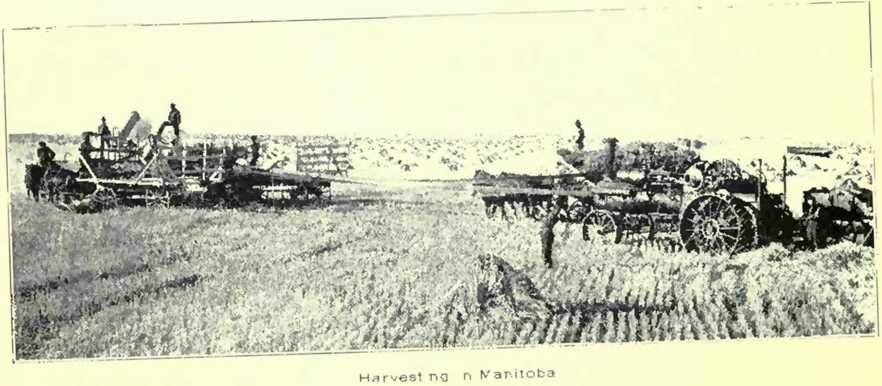

In this country where

large areas of land are cultivated, it is necessary that all farm

operations be expedited as much as possible. For this reason the most

improved machinery is on use on all the up-to-date farms. As soon as the

grain is fairly ripe, large grain-binders are set to work, and kept

constantly in operation from dawn to sunset. Sometimes a score of these

large machines, each drawn by four horses are found following each other

closely around one immense field, and in a few days, hundreds of acres

of ripe grain are safely in the stook. The grain is allowed to cure for

a few days, after which large threshing outfits, consisting of powerful

steam traction engines and separators, are brought into the field where

the threshing is done directly from the stook, and so quickly that only

a few days intervene between the ripening of the grain and its delivery

on the market. At the present time the prospects for agriculture in the

Province are bright; the prices of farm products are high, the area

under cultivation is increasing rapidly, and the employment of improved

conditions of agriculture should result in larger returns than in former

years.

THE LIVE STOCK INDUSTRY

OF MANITOBA

In the early days of

the settlement of Manitoba, Live Stock was considered the mainstay of

agriculture, for some little time was necessary to enable the settlers

to discover the possibilities of soil and climate for the production of

wheat. Many of the early pioneers brought with them a foundation stock,

and in not a few of the best studs and herds of to-day can be traced a

descent from those early importations. Needless to say, the stock

imported from the older provinces thrived wonderfully on the nutritious

prairie grasses, which for many generations had sustained vast herds of

buffalo. The pioneer delights to recall the big steers he produced when

the herds fed on the short sweet upland pastures or revelled belly-deep

in vetches and wild pea-vine. An opening having been made for the export

of wheat by the completion of the railroad between the prairies and the

lake ports, the wealth-producing possibilities of grain growing were

quickly recognized. It happened that the open prairie was easily brought

under cultivation. No expensive equipment was required, an easy credit

system prevailed, wonderful returns were obtained, and settlement

rapidly increased. As a result the live stock interests were neglected,

and wheat became the one thing considered worthy of attention.

Many a traveller has

marvelled at the myriad beacon fires that illuminate the autumn sky from

the far-reaching stubble fields, where the straw piles are burned as

soon as the threshers have completed their task. This improvident waste,

coupled with careless methods encouraging the introduction and spread of

weeds, is causing the pendulum to swing slowly back again. In order to

improve the mechanical condition of the soil, to restore exhausted

fertility, and to control noxious weeds, grasses and clovers are being

introduced, farms are being fenced and the rearing of live stock is

again receiving serious attention.

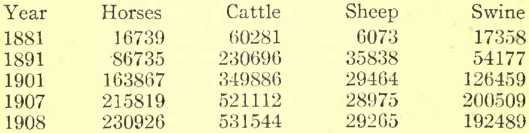

The following figures,

taken from Government statistics will give some idea of the growth of

the live-stock industry:—

The demand for horses

is still greater than the local supply. For a number of years, horses

have been shipped into Manitoba from the Eastern provinces, the Western

ranges, and from the States to the South. During the past year, however,

Manitoba-bred horses, mostly for farm purposes, are beginning to appear

in considerable numbers on the Winnipeg market. The keen demand which

exists, and the good prices obtainable, are stimulating the breeding of

horses. In addition to several breeding studs which have been

established, many farmers are procuring good brood-mares, not a few of

which are registered mares of the draft breeds. For many years a

considerable business in the importation of stallions has been carried

on. Importers from the United States have not only brought with them

American-bred stallions, but have also introduced their methods of

disposing of these. One of the methods referred to is commonly known as

"syndicating." Ten or a dozen farmers are induced to take shares in a

stallion, signing joint notes therefore. In many of these cases, the

stallion so disposed of is stated to be worth from $2,000 to $4,000,

which is generally three or four times its actual value. The notes are

of course discounted before maturity, and the salesmen decamp. Such

practices have done much injury to the horse-breeding industry but

happily they are now almost a thing of the past. Several large dealers,

permanently established in the West, import direct from Great Britain,

and Ontario dealers may now be expected to take greater interest in

supplying Manitoba with good home-bred and imported stock horses.

Legislation has been

introduced by the Western Provinces to encourage horse-breeding. The

object of such legislation is educational, and the intention is to

encourage the use of sound, pure-bred stallions, and to eliminate the

unfit. Owners are compelled, under a penalty, to register stallions with

the Provincial Departments of Agriculture; certificates are then issued

stating whether the animal is pure-bred, or graded, soundness, or the

reverse, also being indicated. A copy of this certificate must then be

printed on all advertisements and route bills, which must be

conspicuously posted on the door of every stable occupied by the horse

during the breeding season. By this means the farmer is enabled to know

the breeding value of the stallions he employs.

The draft breeds are

undoubtedly the most popular with the farmers, and of these, the

Clydesdales take first place. A few Shires have been introduced, and,

during the past few' years, a good many Percherons. The latter would

appear to be slowly gaining in popularity. As there are, however, many

registered Clydesdale mares throughout the country, and in nearly every

section, a good representative Clydesdale stallion, this breed is likely

to hold its own for a long time to come. Of the horses bred on the

average farm, few would scale up to the “draft" class, the majority

having to be classed as “agricultural’’ horses, weighing less than 1,600

lbs., while there are many horses bred from small nondescript mares that

could only be classified as "farm chunks," a useful enough horse on the

farm, although lacking in weight, but hardy, and generally with good

wearing qualities.

Of the lighter breeds,

comparatively few are bred, although there are many American trotting

stallions in the country and some excellent road horses are produced,

These are always in good demand, provided they possess sufficient size

and quality. Thoroughbreds, Hackneys and some of the Coach breeds have

been introduced in various parts of the Province but, so far with little

marked effect upon the horse industry. Some saddle, and heavy leather

horses are produced, but most of these crosses are what may be called ‘

‘ General Purposes” horses. This is a good, useful class, fit for all

kinds of light farm work and for certain kinds of road work, but it will

not command high prices in the market

The country on the

whole is well suited for horse breeding. The climate is healthy, and

feed of good quality is abundant. There are, however, some difficulties

to contend with. The most serious of these is, perhaps, the mortality

among foals, from the disease known as “joint ill,” and other little

understood pathological conditions, which are attributed to insufficient

exercise on the part of the mares during the long idle winter season.

Another disease, which is confined to the lower-lying districts of the

Province, is commonly known as “swamp fever,” an intermittent fever of a

low type, not as yet thoroughly understood.

The cattle industry has

advanced with the settling of the country, and, with improved market and

transportation facilities, will doubtless become one of the most

important branches of agriculture.

Manitoba cattle are of

a healthy breed, and cost little to keep, for there is everywhere an

abundance of suitable fodder. On the smaller farms (and most of those in

the extreme eastern and north-eastern portions of the Province, come

under this category) cattle of the dairy type predominate. By this it is

not meant that the special dairy breeds are exclusively used, as most of

the cattle in these sections, as well as throughout the province, show

more or less of Shorthorn strain.

The little Red River

cow of earlier days, rugged, vigorous, big middled, short-legged,

crumple-horned, line-backed or brindled., has almost entirely

disappeared. The foundations of several herds of Shorthorns were laid in

the early eighties, and the progeny of these, and of many subsequently

established, have been widely distributed throughout the country. The

blood of this cosmopolitan breed now flows in the veins of nearly all

our cattle. Other breeds have been introduced, but still the Red, White

and Roan numerically holds supremacy, and at all leading Exhibitions

outnumbers other breeds in the proportion of two to one. There are now

in Manitoba over 350 members of the Dominion

Shorthorn Breeders’

Association, and their favourite breed of cattle seems in no immediate

danger of losing in popularity. Breeders should, however, endeavor to

revive the milking qualities of the breed in order that it may continue

to hold the position of ‘1 Farmers ’ cow. ’ ’

Of the special "beef

breeds," the Hereford and the Aberdeen Angus are fairly well

represented, and a number of good breeding herds exist. Where the calves

run with their dams, and beef-production only is desired, either of

these breeds, or the Galloway, thrive abundantly. They are good grazers

and feeders and mature heavy, compact carcases of beef of the best

quality. The females, however, are not so useful as "Farmers cows,"

since they are not such good average milkers nor as docile as the

Shorthorn.

Of the dairy breeds,

the Holsteins seem to be steadily gaining in favour. They are robust and

large-framed, with great capacity for the assimilation of "roughage,"

and produce immense quantities of milk of fairly good quality. There are

several excellent pure-bred herds in the Province. The Ayrshire and the

Jersey, have their fanciers, and small herds have been in existence for

a good many years. The last named breed has made no headway, but the

first is numerously represented in the dairy districts, and vigorously

contests every inoh of ground with her big black-and-white sister.

Year by year, furrow by

furrow, wheat has crowded back the herd from the sweet grasses of the

upland prairies on to the lower-lying flatter lands, where ttv grasses

grow coarse, sedgy, and less nutritious. Un such circumstances, cattle

have suffered some deter/ tion, but with the introduction of more

"intense" methods, including the growing of com, clover a/ falfa, with

greater attention to sanitation of s' and the adoption of less laborious

methods of for stock, better results will accrue.

There are already

indications that cattle-feeding will be carried on more extensively in

this Province. The straw and chaff and screenings of the wheat farms

will “be marketed on the hoof" and the manure thus created will restore

the fertility and improve the mechanical condition of the soil,

resulting in better yields of superior quality, and hastening the

maturing of the crops. As in the com belt of the States, the cattle from

the ranges of the West will be “finished” on their way to the world’s

markets, on the wheat farms of Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

It is sometimes said

that swine-breeding on any extensive scale cannot be profitably carried

on except in conjunction with dairying, or under such conditions as

exist in the com States to the South. To a certain extent, that is true.

Every farmer can, however, at a minimum expense, even without milk,

produce a few' hogs on by-products that would otherwise be wasted It is

necessary, however, to raise the hog in a cheap way, making him utilize

pasture grass, rape, roots and “roughage,” and then finish quickly on

“concentrates.” At the present time there is not sufficient pork

produced in the West to supply the local demand, but, as previously

indicated, the market conditions are not such as to encourage the

industry. The demand being for light, mild-cured bacon and hams, the

bacon type of hog is preferred to the lard type, consequently the two

great bacon breeds, the Yorkshires and Berkshires, have virtually taken

possession of the trade. A few Tam-worths are also bred, and their

impress may be noticed m the Stock Yards. One or two small herds of

Chester Whites and Poland Chinas are also maintained in the Province,

but they are not kept in sufficient numbers to affect the general type

of the market hog.

Sheep-breeding in the

Province has been losing ground for the past fifteen years. This is not

due to unsuitable conditions of climate, for sheep thrive remarkably

well m this clear, dry atmosphere. Neither is this condition of the

industry attributable to unfavourable markets, for prices for lambs and

mutton—sheep of any kind— rule high. The market is supplied from the

ranges of the West, from Ontario, and the Maritime Provinces, and even

frozen mutton from Australia has found its way into the Winnipeg market.

The one great enemy of the shepherd in the West is the coyote or prairie

wolf. While governments and municipalities offer bonuses for wolf

scalps, the breeding grounds of the wolves are so extensive, stretching

as they do into the Northern wilds, that the only immediate remedy

against their depredations would seem to be the protection of the flocks

by means of fences. Provision of this nature will undoubtedly be

provided ere long by many farmers. Flocks of many of the leading breeds

have been established. Any of the medium wooled breeds are suitable. The

Shropshires and the Oxfords have proved popular and useful, especially

for “grading up” the common merino-grade range ewe. Leicesters are also

strong favourites and have made conspicuously good exhibits at our

leading exhibitions.

Early in the live-stock

history of the province, active Associations were organized, and through

the agency of these, public interest has been stimulated in the

important work of live-stock improvement. Valuable concessions in regard

to freight rates for pure-bred stock have been obtained from Railroad

Companies. Exhibition Associations have been induced to employ more

efficient judges and to provide larger prizes and more adequate

accommodation for live-stock. Provincial auction sales of pure bred

stock have been inaugurated, and farmers have thus been enabled to

select bulls for breeding purposes, from among the consignments of many

breeders.

Within the last year or

so a very successful Winter Fair, Horse Show and Fat Stock Show has been

established at Brandon, under the auspices of these associations, where

practical demonstrations in live stock judging are given and lectures

delivered on various phases of the industry.

DAIRY INDUSTRY IN

MANITOBA

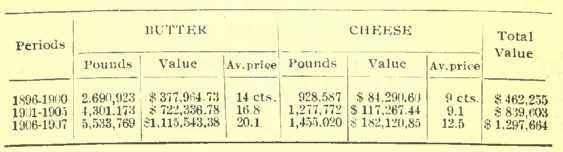

Careful consideration

of the past and present conditions of the Dairy Industry in Manitoba,

justify a feeling of optimism as to its future. Although this industry

is still in its infancy, it has made steady progress as a reference to

the following table will show:

Average annual yield

and value of butter and cheese by five-year periods.

While this table fairly

represents the growth of the industry, it does not indicate either its

magnitude or its value to the Province, since it does not take into

account the town and city milk and cream supply and the "by-products"

fed at the farm. When it is remembered that the town and city population

constitutes somewhat more than fifty per cent, of that of the Province,

it is readily seen that there is a large quantity of milk and cream

consumed as such. The columns of average prices, given in the foregoing

table, are quite as worthy of note as those indicating the growth of the

industry, since they point to the growing demand for dairy products at

increasingly remunerative prices.

Our native and

cultivated grasses are both suitable for the production of a fine

quality of milk, suitable for the making of excellent butter or cheese.

We can grow in abundance, suitable - soiling crops for supplementing the

pastures when necessary, such as peas and oats, alfalfa (in many parts

of the province) and com. Furthermore, we can successfully grow such

crops as mixed hay (clover and timothy), brome grass, alfalfa, com,

roots, and the coarser grains for fall and winter feeding. With the

right kind of cows, properly eared for, no trouble is experienced in the

production of milk economically and in quantity.

The beef breeds of

cattle, particularly Shorthorns, predominate in the Province. These were

introduced in the early days when every farmer was surrounded with all

the grazing land he desired. Later, as the country became more generally

cultivated, dairying was combined with beef production, and, as a

result, particularly amongst the Shorthorns and Shorthorn grades and

crosses, many very creditable and even excellent general or

“dual-purpose” cows, whose milking qualities have been developed by

careful selection. In addition to these there are, in the Province,

several excellent pure-brcd herds, representative of the Holstein,

Ayrshire and other dairy breeds. The Holsteins probably being, at least

in so far as numbers go, in the ascendency. Many good dairy grades are

also to be met with.

A ver}' considerable

portion of the Province, particularly in the east and north, is much

more suitable for mixed farming than for grain growing. Even the present

grain districts cannot sustain indefinitely the continued impoverishment

resulting from the continual production of grain crops. Continuous

grain-growing has additional bad result of increasing the number of

weeds. To restore and maintain soil fertility, and to eradicate weeds,

the adoption of a suitable rotation of crops is imperative. Along with

this would naturally be introduced a certain amount of stock rearing.

Thus dairying would in due course occupy a prominent part in any

thoroughly satisfactory scheme of farming. The present conditions of the

dairy market are encouraging, the home market especially is rapidly

developing.

One feature of the

Manitoba dairy industry is the extent to which the manufacture of butter

and cheese has become co-operative. Although the Province is yet

sparsely populated, fully fifty per cent, of the butter and cheese put

upon the market is made in factories.

There are in the

Province about forty cheese factories, situated in the more thickly

settled districts. But there is greater scope for butter-making and

cream gathering.

There is at the present

time, a marked tendency towards the centralization of the creamery

industry. This is encouraged by the co-operation of the Express

Companies, who give reduced rates on cream for butter-making purposes.

This system has its advantages, and its disadvantages. Among the former

are a larger output, better equipment and a more economical production:

while among the latter may be mentioned a lack of interest on the part

of the producer in the scientific work of the creameries.

HORTICULTURE IN WESTERN

CANADA

In considering the

agricultural possibilities of the Province of Manitoba, the subject of

horticulture is too frequently overlooked or given scant consideration

The fact that cereals can be grown with splendid success has been very

clearly demonstrated, but up to the present time comparatively few of

the people residing in Western Canada, have had sufficient confidence in

the fruit growing possibilities of the country to enter into the

industry on a very extensive scale. However, a few pioneers have paved

the way and to the results of their work we look for encouragement and

guidance.

In a country of such

rich agricultural resources as Manitoba, where excellent crops of

cereals can be produced on an extensive scale with a minimum amount of

labor, one would naturally expect that the people would turn rather

slowly to the production of fruits which require much greater care and a

much more “intensive” system of cultivation. The growing of this finer

class of agricultural products is usually delayed until the country has

become thickly populated and the land has been brought into a fairly

good state of cultivation. Making an allowance for the difficulties

which have to be overcome in the production of fruits, some splendid

work has been done and substantial progress made. Attempts in fruit

growing have been made since the first settlement of the country. The

first experimenters were greatly handicapped by a lack of information

regarding the suitability of the country, and many mistakes were made.

The introduction of tender varieties was attended with failure, and it

was only at considerable personal expense that the early growers learned

that only the hardiest fruits obtainable were suited to this rigorous

climate. Since this lesson has been learned steady progress has been

made. Experiences have resulted in great efforts to secure hardy

varieties of apples, plums, cherries and other fruits from countries

where the climatic conditions are similar to those of Manitoba. The

Experimental Farms have given splen did assistance in this work and have

been instrumental in introducing some fruits that undoubtedly will be of

great value in future years.

Among the valuable

introductions is the Pyrus Bacata or Siberian Crab Apple, which was

first planted on the Experimental Farm at Brandon, in the year 1890, the

trees having been grown at the Central Experimental Farm, Ottawa, from

specially selected seed that had been imported from Russia. The

introduction of this hardy Russian apple has done much for the

advancement of apple growing in Manitoba. It furnishes a hardy stock on

which the tenderer standard varieties may be grafted and their hardiness

very much increased. Dr. Saunders, Director of the Central Experimental

Farm, Ottawa, has also endeavoured to increase the hardiness of some of

the standard varieties by hybridizing them with the Pyrus Bacata.

Several promising hybrids have been produced in this way and are now

being grown to some extent in the Province.

Among the earliest

attempts in fruit growing in the district of Winnipeg, may be mentioned

those of the' late Mr. W. B. Hall, of Headingly. In the early sixties

some not unsuccessful experiments were conducted by him with currants,

tomatoes, gooseberries, Siberian crab apples and rhubarb. The results

were indeed so satisfactory that he and others in the neighborhood were

induced to carry on fruit growing on a large scale. Among other pioneers

whose experiments on fruit growing have been of value, may be mentioned

the late Mr. Thomas Frankland, of Stonewall, and Mr. A. P. Stevenson, of

Dunstan. Mr. Stevenson has experimented very largely with plums,

cherries, grapes, gooseberries, currants, raspberries and strawberries,

and his untiring efforts in this direction have been a great incentive

to others within the province to interest themselves in the growing of

fruits. His work, together with the work that has been done on the

Experimental Farms, has demonstrated very clearly that hardiness is one

of the first essentials, a fruit suited to the Province of Manitoba.

From the time of the introduction of the crab apple and the hardy

Russian sorts may be said to date the first successful attempt at apple

culture in this province.

The Experimental Farm

at Brandon, under the direction of Mr. S. A. Bedford, has done a great

deal for Manitoba horticulture. Hundreds of varieties of the various

classes of fruits from different parts of America and Europe have been

tested there and the results published. In the month of April, 1S99,

about five hundred fruit trees, consisting of apples, crabapples, plums

and cherries, were placed under test at the Experimental Farm. These

included many of the large standard varieties together with a number of

hardy imported kinds. Numerous varieties of grapes, currants,

gooseberries, raspberries, blackberries and strawberries were also

tested. Many of these trees did not survive the first winter and in a

few years only the hardiest sorts were found to be alive. Since the

first planting, many other varieties of fruits have been introduced and

experimented with and much valuable information has been gained. Among

the numerous introductions was the Russian-Berried Crab Pyrus Baccata.

Its extreme hardiness makes it eminently suitable for this country. It

is used as stock on which the less hardy standard sorts are grafted, for

the purpose of increasing their hardiness and thereby adapting them to

an environment that would otherwise be uncongenial to them.

Small-fruit culture in

the Province of Manitoba has always been attended with a very fair

degree of success. Currants, gooseberries, red and black raspberries,

and strawberries have been grown since the early settlement of the

country. They yield profitable returns when intelligently cultivated.

They apparently possess an inherent hardiness not shared by many

tree-fruits, and this renders them much more suitable for the severe

climate. It is only a matter of a few years until these smaller fruits

will be grown in all parts of the Province, in sufficient quantities to

supply the local demand. Another phase of horticultural work to which

considerable attention is being given, is the decoration of home and

school grounds by the planting of ornamental trees, shrubs and flowers.

The prairie is bare and unattractive and round many prairie homes there

has been a lack of trees and shrubs. The work of beautifying the

surroundings of residences is the most necessary step in the

horticulture of the Province of Manitoba, and a great deal is being done

in the cities, towns and rural districts to increase their

attractiveness by ornamental planting.

In regard to the

growing of vegetables the Province occupies a splendid position.

Practically all garden vegetables with the exception of a few that

require a long season, may be grown to a high state of perfection. The

richness of the soil and the shortness of the seasons tend to give a

flavour and tender crispness not attainable elsewhere, to the

vegetables.

The splendid yields

that may be obtained from these fertile fields make vegetable growing a

very profitable branch of agriculture, as there is an abundant demand in

the home market.

The work of fostering

the cause of horticulture within the Province is carried on largely by

the Agricultural College and certain societies; among these are the

Western Horticultural Society, the Brandon Horticultural and Forestry

Society and others of a more or less local character. The objects of

these societies are to bring together those persons interested in

horticulture, to gather together horticultural literature and to

stimulate in every possible way a greater interest in horticultural

pursuits. Much good work has been accomplished by these societies and to

their efforts is largely due the irf creasing interest that is being

taken in the various lines of horticultural work within the Province.

There are several

directions in which progress may be made in Manitoba horticulture; for

example, a better selection of varieties; an improvement by breeding and

selection of wild and native fruits and varieties grown in the country;

and by improved systems of culture. Much is being done in plant

improvement, and the Province of Manitoba offers an excellent field for

the improvement of native fruits. Various wild fruits grow very

abundantly in many parts of the Province, and if a combination could be

effected whereby the hardiness and productiveness of these could be

combined with the larger ske and better quality of the cultivated fruit,

a great step in advance would be achieved.

POULTRY RAISING

The possibilities of

the poultry industry in Manitoba are just beginning to be understood.

When the country becomes more thickly populated and mixed farming is

more generally practiced, poultry raising will no doubt occupy a

prominent place on the farm. To many people living in small towns in

Manitoba, a flock of hens is sufficiently profitable to be a source of

considerable income. The question is sometimes asked: “Is the return

likely to be sufficiently great to render it worth while to devote one’s

entire energies to the rearing of poultry?”

The best reply to this

question may be deduced from the following facts:—

From the Province of

Ontario and the Northwestern States, over one million pounds of dressed

poultry, having a value of at least from $150,000, were imported into

Winnipeg for its own consumption during the past winter. From the same

districts no less than 4,500,000 eggs, of a total value of about

$100,000, were brought into the city during the winter. Thus we see that

the City of Winnipeg with 10,000 inhabitants imports for its own

consumption about $250,000 worth of poultry and eggs each year. To these

figures must be added the amount imported for Brandon and some of the

other larger towns.

The above mentioned

values of poultry products imported into the Province are so great that

the industry ought to be a good investment. It has been estimated that

in the neighborhood of Winnipeg alone, there are openings for about

fifty poultry farms. A serious drawback to profitable poultry keeping in

Manitoba is the extreme cold during some of the winter months. But since

the air is remarkably dry this disadvantage may easily be exaggerated.

It is, however, necessary that adequate protection should be afforded

the poultry during the severe weather.

MARKETS AND MARKETING

Coincident with an

increase in the area of cultivated land, improvement has been made in

the organization of systems of marketing farm products. In no particular

is this more apparent than in the building up of the grain trade of the

West. Primarily, a grain-producing country, her whole prosperity bound

up in the annual product which a bounteous nature gives her, it is but

natural that Manitoba should find the business of handling the crops, so

as to bring them to the various markets of the world, a task of the

first magnitude. This is no less urgent a duty than the actual

production of the crops.

Six different railway

companies now run trains to Winnipeg. These give complete connection

with every part of the continent, and their branches radiating to all

parts of the West make it easy for the farmers to transport their

products to the world’s markets. By statutes of the Canadian parliament,

all inspection certificates for grain or other products that come under

inspection in Western Canada, must be issued by inspectors in Winnipeg.

The Western crop of 1908, was estimated at over two hundred and

thirty-six million bushels, about eighty-five per cent, being marketed

for export. All of this amount passed through Winnipeg and went out

bearing Winnipeg Inspection Certificates. Of the total Western crop

Manitoba produced 113,058,189 bushels of grain, nearly one-half of which

was wheat. From the crop of 1909, Winnipeg grain dealers will handle

enough bread stuffs to furnish a year’s supply for all the inhabitants

of Canada, and 10,000,000 people besides.

For the handling of

this grain, there are in Western Canada, 1,41(5 elevators and 41

warehouses with a total capacity of 43,037,000 bushels. Most of these

are situated on the Canadian Pacific or the Canadian Northern Railway.

In the Province of Manitoba, on the Canadian Pacific Railway, there are

4(52 elevators and 12 warehouses with a total capacity of 14,574,000

bushels, while on the Canadian Northern in the same Province there are

205 elevators and two warehouses having a total capacity of 5,921,000

bushels. Besides these elevators, at every station there is built a

loading platform over which a farmer may load grain from his wagon

direct to the car, thus allowing him to ship his grain independent of

the elevator companies. During the marketing of the crop of 1908, about

33 per cent, of the grain was shipped in this way.

The marketing season

usually begins early in September, and a great bulk of the grain is

disposed of before December. All the grain handled in this space of time

is reloaded at the lake ports, Fort William and Port Arthur and shipped

by lake. At these points thirteen elevators, classed as “terminals,” are

owned and operated as follows:—

At Port Arthur,

Ontario, the Canadian Northern Railway owns two, with a joint capacity

ot 7,000,000 bushels. These are operated by the Port Arthur Elevator

Company. There is also-at Port Arthur, the elevator of Jos. G. King and

Company, with a capacity of 800,000 bushels. This elevator is on the

line of the Canadian Pacific Railway At Fort William, the Canadian

Pacific Railway owns and operate three, with a respective capacity of

2,258,000; 2,209,700 and 1,221,000 bushels each. Four other elevator

companies have storage capacity amounting to 2,360,000 bushels.

At Keewatin, Ontario,

the Lake of the Woods Milling Company have two milling elevators having

a capacity of 700,000 and 500,000 bushels respectively. And at Kenora,

the Maple Leaf Flour Mills Company own one that will store 500,000

bushels.

The greater portion of

the grain taken into the hun dreds of smaller elevators in the West, and

shipped from loading platforms at country points, finds its way into the

above mentioned terminals at the Lake front and is shipped from there to

its ultimate destination, the bulk going by vessel to Georgian Bay

ports, Montreal and Kingston, although last year close on to 9,000,000

bushels went to Buffalo and other United States ports. In addition,

1,571,940 bushels were shipped in 1908, by rail over the Great Northern

Railway to Duluth. During the crop year of 1907-1908, there was a total

shipment of 02,107,513 bushels, and of this 47,743,330 bushels were

shipped by boat, and 14,364,177 went by rail. The total amount invested

in terminal and country elevators and warehouses in the Manitoba Grain

Inspection Division is approximately $11,707,000.

The rates in force at

Public Terminal Elevators are —

For receiving,

elevating, cleaning, spouting and insurance against fire, including

fifteen days free storage, 5½ cent per busfiel. When it is necessary to

re-clean grain in order to ascertain the amount of domestic grain of

commercial value contained in the screenings, a charge of one-half cent

per bushel is made for extra treatment.

Foremost in the

business interests of the West, stands the Winnipeg Grain Exchange,

which, in the comparatively short space of twenty years, has reached an

enviable position among the leading grain institutions of the world. The

Winnipeg Grain and Produce ‘Exchange was incorporated in 1891, after

having been organized for several years. Commencing with a membership of

ten, and an entrance fee of $15, the Exchange has, in less than two

decades, reached such a commanding position that the leading grain

dealers of the continent consider it imperative to become members. The

value of the seats has reached $2,500, and the membership numbers 300.

The objects of the

Exchange, as outlined in the articles of incorporation, were declared to

be—“to compile, record and publish statistics, and acquire and

distribute information respecting the produce and provision trades, and

promote the establishment and the maintenance of uniformity in the

business, customs and regulations among the persons engaged in the said

trades throughout the province, and to adjust, settle and determine

controversies and misunderstandings between persons engaged in such

trades.” The record of the past years clearly indicates that these

objects have been fully attained.

Through the efforts of

the Exchange, permanent standards have been secured for the various

grades of grain, and those have proved of great benefit to both the

producer and grain dealer throughout the West.

The different grades

are named thus:—“No. 1 Manitoba Hard,” “No. 1 Manitoba Northern,” “No. 2

Manitoba Northern,” “No. 3 Manitoba Northern,” “Commercial grade No. 4,”

“Commercial grade No. 5,” “Commercial grade No. 6,” “Commercial grade,

feed.” The grade “No. 1 Manitoba Hard,” consists almost altogether of

hard, red, plump kernels. In every hundred only about three immature,

shrunken kernels are allowed and the sample must be practically free

from “frosted” kernels, i.e., kernels with pale, roughened skin, due to

the action of frost or water, and there must be no appreciable odor of

smut.

“No. 1 Manitoba

Northern” is distinguished from “No. 1 Hard,” chiefly by the larger

proportion of starchy kernels present , and of those which are somewhat

shrivelled. It has about ten shrunken kernels in every hundred, and is

practically free from kernels showing the action of water or frost. “No.

2 Northern” is very much like “No. 1 Northern,” but with a slightly

larger proportion of defective kernels, about twelve in every hundred.

“No. 3 Northern” contains about twenty-three defective kernels in every

hundred. “No. 4” has about thirty defective kernels in every hundred,

while “No. 5” contains about fifty-six defective kernels, forty of which

may be shrunken. "Commercial grade No. 6” contains about sixty-five

damaged kernels, while Commercial grade rated as "feed" contains about

eighty-eight defective kernels in every hundred, and the sample usually

possesses a distinct odour of smut.

In the prices received

for those different grades, there is considerable variation. “No. 1

Hard” always sells for one cent more than “No. 1 Northern,” while there

is a difference of from four to six cents between each of the following

grades. During the four months from September 1st, 1908, to January 1st,

1909, about 83 per cent, of the crop was marketed. The average price for

all grades of wheat has been estimated m one computation at 85 cents,

and with the price for “No. 1 Northern” hovering about a dollar, as was

the case during those four months, this average may be considered fairly

representative. The price of oats held fairly steady between 35 and 40

cents, and, if allowance be made for low grades and freight rates, the

average return to the farmer may be placed at not less than 27 cents per

bushel. Barley held up in price throughout the season and has been

valued at the rate of 40 cents per bushel.

Manitoba is not merely

a wheat growing and exporting country. Every branch of farming has made

rapid strides of late years. The products include oats, barley, flax,

rye and peas; the Manitoba root crop alone amounts to 8,568,386 bushels

and the dairy products to 3,918,568 lbs. of the value of $10,604.31.

The development of the

live stock trade has been very great. This is shown by the increase in

the stock marketed. The past year was an excellent one for the rearing

and shipping of live stock, the receipts at the Winnipeg stock yard were

nearly double those of any similar period. Not only is there much

improvement in the number of cattle marketed, but also in their quality.

The total receipts at Winnipeg for 1908, were 170,088 head, and of these

about 91,045 cattle were suitable for export. The remainder were sold as

"stackers’' and "feeders."

Many farmers now ship

their own cattle and do their own selling on the market. This fact has

made the competition much keener between buyers than it was previously.

However, most of the arrivals of butchers ’ and feeders’ stock are sold

by farmers to buyers in the country, who again sell to dealers in

Winnipeg. The prices for average export cattle have been about $47 per

head at the shipping point. For butchers’ stook the average price to the

farmers has been about three cents per pound. This price is small but is

accounted for very largely by the fact that the Winnipeg market for

butchers was glutted during most of the past season. A number of

"butchers" and "feeders" were taken East to Toronto and Montreal, and

others, South to St. Paul and Chicago. The Winnipeg market, however,

provided for nearly 64,000 head, a number slightly out of proportion to

actual requirements. Each year a greater number of these cattle are

being "fitted" before being marketted, and, as this process becomes more

general, the price will improve.

The average weight of

the "butchers" and "feeders" at Winnipeg, was 1,061 pounds, in 1908, and

the average price $3.53, giving a total value of $2,960,483 for one

year. The total amount paid out for cattle at the yards was $7,245,589.

It is believed that the

West will become a great hog-raising country. In the year 1908, there

was an increase of 63,040 as compared with the previous year, the total

receipts at Winnipeg numbering 145,209. The yearly packing capacity of

Winnipeg, is 450,000. The Winnipeg market price for hogs is very largely

controlled by the price for which bacon can be brought in from the

United States. Hogs, like butchers’ cattle, are mainly bought in

Winnipeg through middlemen, but the prices vary less than for cattle.

The average price paid last season was $5.70 per cwt. at Winnipeg, and,

to the farmers at their own station, about 5 cents per pound.

The sheep industry is

not yet very extensive. The mutton receipts show each year but slight

increase, as Winnipeg still continues to bring frozen mutton from

Eastern Canada during the past year; as much as eight cents per pound

was paid on the hoof for lambs off cars at Winnipeg. The live stock

industry in Western Canada is still in its infancy, but there are

already indications of a considerable increase in a very short time,

Farmers are beginning to realize that the fertility of the soil must be

retained, and that this is best done by the rearing and feeding of live

stock.

AGRICULTURAL EDUCATION

The Province of

Manitoba is so young that most of its industries are still in the

making. The first and par amount of these is farming, but even this is

only in its infancy. “Extensive” rather than “intensive’’ methods have

been followed. The farmers reaped crop after crop of wheat until they

found that their land would not continue for many years to respond to

this treatment. To-day in Manitoba, conditions are such as to demand the

employment of more scientific methods of agriculture. To disseminate a

knowledge of these is the function of our system of agricultural

education.

Until within the last

few years, agricultural education has been carried on by the

Experimental Farms, the Agricultural Societies, the Breeders’

Association, and the Agricultural Press. The first Experimental Farm was

founded by Lord Selkirk, in 1810, at Hayfield, and was carried on until

1822. In 1837, the Hudson’s Bay Company founded an Experimental Farm a

short distance from Fort Garry, on the Assiniboine River. This farm also

had only a short career of some ten or eleven years. In 1888, the

Dominion Government called upon Dr. William Saunders and Professor S. A.

Bedford, to choose sites for two farms in the West. These are situated

at Brandon and Indian Head. The farm at Brandon was ably managed by Mr.

Bedford, tor over eighteen years. During this time good work was done

for the West in introducing early ripening varieties of wheat by

experiments in raising and feeding stock, and in the testing of fruit

and forest trees, as well as grasses and fodder plants.

The Provincial

Department of Agriculture has been active, also, in educational work,

and has always been generous in making grants of money to the

Agricultural Societies, Farmers’ Institutes, Dairy Association,

Breed-res’ Association, and Horticultural Society, and in other ways.

Farmers’ Institute meetings have been •held in Manitoba ever since 1890,

and Agricultural Fairs since 1892. Reports show that 56 Agricultural

Fairs and 122 Institute meetings were held in Manitoba during the year

1908. In the winter of 1907-1908, the Provincial Government offered $50

to each of ten Agricultural Societies if they would subscribe equal

amounts in order to hold Seed-Grain Fairs. This experiment proved so

satisfactory that the offer has been made general, with the result that

some thirty fairs were held during the past winter. The summer of 1908,

was the first in which farming competitions were held, although previous

to this, prizes had been offered for the best fields of standing grain.

Special mention should be made of the judging-schools, which have been

held since 1902, under the auspices of the Live Stock Association, whose

meetings were formerly held in Winnipeg but are now held in Brandon

during March, in each year. In 1906, a seed-grain special train carrying

a corps of Institute speakers, travelled through the provinces and

called at all the important towns, and in 1907, a special dairy train,

suitably equipped, visited the leading dairy sections of the province.

The magazines giving

space to agriculture .in Manitoba, are the Nor’-^est Farmer, the

Farmers’ advocate, The Canadian Thresherman, Farm Crops, and the weekly

editions of the Free Press, Telegram, and Tribune. The value of such

periodicals in disseminating agricultural information cannot be over

estimated. In the schools, agriculture has been a subject of the

curriculum since 1896. The work prescribed is, however, rather “nature

study” than systematic agriculture. For the High Schools and Collegiates,

a short course in agriculture is outlined, to be taken by pupils

pursuing the Third-Class Teachers’ Course. This covers a brief study of

plants in their relation to water, soil and air; the origin, drainage

and improvement of the soil; the different crops; and the live-stock of

the farm. Experiments are performed in elementary physics and chemistry,

bearing upon agriculture. During the past summer, a further step has

been taken in elementary agricultural education. All second and

first-class teachers are required, while taking their professional

training at the Normal School, to spend one month at the Provincial

Agricultural College.

In 1906, the Manitoba

Agricultural College was opened and 85 students registered in the

general course. The next session 143 were enrolled, while during the

past session 170 were in regular attendance. A special dairy course is

held for those who wish to prepare themselves to manage and operate

cheese factories and creameries in the province. In 1908, a short course

in Engineering was begun to meet the demand for instruction in working

steam and gasoline engines, which are so much used in modem farming.

“Farmers’ Week” at the

college has now become an important factor in agricultural education.

The Agricultural Societies, Dairy Association and Horticultural Society

hold their annual conventions at this time, and, in order to make the

gathering of greater interest to the hundreds of farmers who attend, the

regular classes, are suspended, and short courses are given in

stock-judging, grain-judging and engineering, for their special benefit.

Over half a million

dollars have been spent in the buildings and equipment of the college.

These include a main or administration building, a mechanical and

engineering building, a students’ residence, powerhouse, greenhouse,

principal’s residence, farm foreman’s residence, stock judging pavilion,

and barns. The mechanical building, recently erected, is 100 feet square

and three storeys in height and contains a blacksmith's shop equipped

with 50 forges and anvils, an equal number of work benches in the

carpenter shop, and a machinery department containing all kinds of farm

machinery, such as ploughs, harrows, seeders, binders, mowers, manure

spreaders, hay loaders, packers, wagons, a threshing machine, and steam

and gasoline engines, the majority of which have been presented to the

college. In the stables pure-bred stock—horses, cattle, sheep, swine,

and poultry—are kept for educational purposes.

The work in the regular

course is covered by the following departments- Field Husbandry,

Dairying, Veterinary Science, Horticulture and Forestry, Agricultural

Chemisrty, Soil Physics, Biology, Farm Management, and English. The

regular course extends over a period of two winter sessions of five

months each and is controlled by an Advisory Board, which issues a

diploma in agriculture to each student who completes the two-year course

and returns to the farm to engage in practical agriculture. This Board

is composed of the Minister of Agriculture of Manitoba, two members

appointed by the Lieutenant-Governor in Council, two appointed by the

University of Manitoba, and five by the Agricultural Societies of the

Province. In 1908, the college was affiliated with the University of

Manitoba, and a course has been added for those wishing to proceed to a

degree in agriculture.

A society called the

M.A.C. Research Association was organized in 1907, and has already done

good work.

It has for its object

the making observations and collecting data on agriculture by the past

and present students of the college. The young farmer has every reason

to be grateful for the generous provision which the Province has made

for his education; and it is hoped that before long adequate provision

will be made for the teaching of domestic science. Before many years

have elapsed it will probably be necessary to establish agricultural

high schools throughout the Province, as has been done in Ontario. We

may reasonably hope that the foresight exemplified in our institutions

for agricultural education will produce a race of farmers who will

consider not merely their personal aggrandisement but will have regard

to the advantages to be reaped by posterity from a scientific tillage of

the land. |