|

Commissioner of Indian

Affairs

WESTERN CANADA may be

described as ex tending from the eastern watershed of the watershed Lake

Winnipeg basin west to the Rocky Mountains and from the International

Boundary to the Arctic waters and the Hudson’s Bay.

This territory since

first known to white men has been inhabited by four distinct families of

aborigines: the Esquimaux, who frequent the coasts of the Arctic Ocean

and of the bays and estuaries of rivers opening thereunto; the Dene or

Athabascan, whose habitat extends from the domain of the Esquimaux south

to the Peace and Churchill Rivers and west to the Rocky Mountains; the

Algonquins, extending from Eastern Canada over the country south of the

Athabascan habitat to the International Boundary; and the Sioux or

Dakotah family, whose habitat in Canada is small portions of the

prairies south of the North Saskatchewan River.

The principal branch of

the Athabascan family are the Chipewyan, often on account of the

similarity of name confounded with the Chippewas or Ojibways who belong

to the Algonquin family. Another tribe belonging to the Athabascan

family are the Beavers of the Peace river. The Sarcees, now settled upon

a reserve near Calgary, belong to the Beaver tribe. In time long past

they left the habitat of the race, moved into the Algonquin country, and

remaining there, came to be commonly regarded as a distinct people. The

Slaves, Yellow Knives, Dog Ribs, and other small

tribes of the

Great Slave Lake and Mackenzie River country also belong to the

Athabascan family.

The main divisions of

the Algonquins in Western Canada are the Saulteaux or Chippewas, the

Crees, and the Blackfoot. tribe, which latter originally included the

Bloods and the Peigans. The Assiniboines are the Canadian branch of the

Sioux. They separated from the main group, and in time their interests

became so diverse that they came to be regarded as a separate people,

and in fact joined in alliance with the Saulteaux against the Sioux

nation. The Sioux proper in this country are refugees from the United

States, who escaped into British territory after displaying some of the

worst features of Indian warfare in Minnesota in the year 1862. They had

no claim to lands in Canada, but were allotted small reserves and given

some assistance in stock and implements to prevent them from trespassing

upon settlers’ holdings. Most of these Sioux: have become industrious

and self-supporting.

Apart from family and

tribal distinctions the Indians of Western Canada can be grouped into

two classes— those of the wooded country, and those of the open prairie.

The former made their livelihood mainly by trapping and fishing, and

moved as single families or as small family groups. They did not develop

any well-defined tribal or band organization. As a consequence there was

less conflict among them, and the country which they inhabited was free

from tribal wars. They developed, therefore, a more peaceable

disposition. Being trappers of fur-bearing animals, they first came

under the influence of fur traders.

The Indians of the

prairies formed into bands under the leadership of chiefs, and their

principal means of subsistence was the buffalo. The different tribes

came constantly into conflict.: the Crees of the plains and the

Blackfeet were continually at war, the Assiniboines usually siding with

the Crees. Sometimes tribal jealousy and often the mere desire for

bloody war and barbaric torture, led to the conflict; but the main cause

of strife among the Indians of the plains was the horse. The Blackfeet

possessed herds of horses which grew larger from year to year as a

result of raids upon Indians to the south and beyond the mountains. And

the Crees kept themselves supplied amply with horses for the buffalo

hunt by raids on the Blackfeet. The last great fight between the Crees

and the Blackfeet ended in a pact made upon the Peace Hills that rise

beyond the Battle River—the river taking its name from the fight, and

the hills their appellation from the treaty.

The traders made little

impression for good upon the Indians, and the mission field being vast

and the laborers therein few, it took a long time to bring the

aborigines to any extent under the influence of the Gospel, particularly

those of the prairie country, who were not readily susceptible to its

teaching. Writing as late as 1808, Archbishop Tache described the

Saulteaux as “generally fine men,” with “a very great liking for

intoxicating drink.” “War songs,” he wrote, “still exist there (the

vicinity of Winnipeg), and often in the midst of starvation and

privation they undertake journeys of several hundred miles on foot to

surprise and scalp an enemy who is generally defenceless, and return

triumphantly to perform the war dance and to shout the hideous scalping

song.”

After the Dominion of

Canada, through the British Government, obtained by purchase from the

Hudson Bay’s Company the transfer in 1870 of all the territory which now

forms Western Canada, a comprehensive policy was adopted in dealing with

the Indians of the said territory. In regard to all such portions of the

transferred country as were required for settlement, or for mining,

lumbering or railways, treaties were made with the Indians of the

districts successively needed for such purposes. Though the sovereign

right to the soil was held by the Crown, yet it was recognized that

there was an Indian title that ought to be extinguished before the land

was granted by patent to settlers or corporations. This title is simply

an admission by the Government that the Indians should not be deprived

of their possessory rights without their formal consent and

compensation. Besides the compensation, the Indians were conceded

reserves at places generally selected by themselves. These reserves set

aside for the occupation of the Indians were in most cases so extensive

as to allow one square mile to every five persons, or at the rate of one

hundred and twenty-eight acres for every man, woman, and child. Not onlv

were the Indians thus dealt with, but the Halfbreeds wherever the land

they occupied was covered by an Indian treaty, on account of their

possessing Indian blood, have been allowed lands or scrip to extinguish

the share of title which comes to them through that blood.

The Indian treaties

made under the Dominion Government since 1870 are ten in number, though

one of them, Treaty nine, does not come under the scope of this paper,

as it was undertaken in co-operation with the Provincial Government of

Ontario. Treaties one and two, which cover the Province of Manitoba,

were negotiated in 1871, and the others in different years since, the

last being in 1900. These treaties embrace all the territory in Canada

east of the Rocky Mountains and south of the 60th parallel of north

latitude, except a tract south and west of Hudson’s Bay.

In general the

compensation granted under the treaties was a payment of twelve dollars

for every man, woman, and child on the chief’s signing the instrument,

and an annuity forever of five dollars per head to the ordinary members

of the band, fifteen dollars to each of the headmen, and twenty-five

dollars to each of the chiefs. A uniform suit of clothing befitting

these two ranks is given every three years. An annual allowance of

ammunition and twine is also granted to the hunting and fishing Indians.

And where farming and grazing operations are practicable and engaged in,

a supply of agricultural implements, seed grain, cattle, and carpenter’s

tools are provided. Schools are also established on the reserves where a

reasonable attendance can be secured.

It may be considered by

some philanthropists that the terms to the Indians were not generous.

There was a difficulty on this point. It is not desirable that large

numbers of able-bodied men, Indians or others, should be maintained in

idleness. The promises in the treaties, consequently, were made

moderate. But it was foreseen that, owing at that time to the rapid

disappearance of the buffalo, the only resource of the plains Indians,

and that with the advance of settlement other large game would decrease

in number, a heavy expenditure would have to be incurred by the Dominion

Government to keep them from starvation. This anticipation was

unfortunately too soon realized. In the eighties the expenditure of the

Indian Department for destitute Indians averaged over three hundred

thousand dollars a year. Of late this expenditure has been gradually

decreasing, the report for 1907-190S showing that the cost of supplies

for the destitute in that year amounted to only $143,033. "When the

Indians become almost wholly self-supporting, large annuities would be

burdensome to the country and demoralizing to them as wards of the

Government. The averaging up, therefore, of the very large outlay that

has been incurred in provisioning and educating them during their years

of helplessness and tutelage, with the promises made to them in

the-treaties, has made the allowances to them for the extinguishment of

their title fairly liberal.

A few figures will show

that this contention is not over-stated. As the Indians of the plains

were totally ignorant of agriculture and the care of stock, farm

instructors hud to be appointed for grain and vegetable raising

reserves, and cattlemen for the stock ranges, to train them for their

new duties. These, with agents for reserves or groups of reserves, and

inspectors to report upon their work, make the administration of Indian

affairs somewhat expensive. Taking this outlay into account, along with

$271,365 for schools, for the supplies already mentioned, and for the

provisions under treaty, the expenditure on Indians in Western Canada in

1907-1908 was $792,979. This amount cannot well be decreased in the near

future, because, though the plain Indians are becoming self-supporting,

the others who live by the chase, owing to the increasing scarcity of

fur-bearing animals and large game, will require considerable assistance

from the Government. It may be set down, therefore, as almost a

certainty that the expenditure of the Indian Department will not for

many years be much less than $800,000 per annum. This sum capitalized at

three and a half per cent, amounts to about $22,800,000—-a fairly just

sum to pay for the extinguishment of the Indian title to the lands in

the western provinces and territories.

As has been already

stated, when the buffalo disappeared, provision had to be made for

feeding the Indians of the plains who had depended upon the herds for

food, for clothing, and for lodges. Ration houses had to be established.

They met the urgent need, but incidentally did not operate for good.

Free food does not tend to the uplifting of men, and when the system was

once inaugurated, it took long and careful work to bring about its

restriction.

In the Blood Agency

five years ago 450,000 pounds of beef were issued free to the Indians.

During the last fiscal year the issue was only 139,000 pounds. At this

rate it will be seen that the time is not distant when the issue will be

restricted to those who are unable, through age or physical infirmity,

to provide for themselves. In 1902 the free issue of beef to the Peigan

Indians amounted to 210,410 pounds; in 1900 it was reduced to 04,504

pounds. Last year there was a further decrease of 1,004 pounds. This

band is now practically self supporting, only the aged and infirm being

provided for. On the Sarcee reserve the free rations continue to

diminish towards the vanishing point. In the Stony Agency, where the

Indians turn their beef into an abbatoir to be held for their own use,

there were 0,142 pounds at the credit of the Indians, and to those who

had exhausted their supply there were loaned but not given gratis, some

1,000 pounds. On the Blackfoot reserve the earning power of the Indians

in the past two years is estimated to have increased fifty per cent.,

and now, outside of those incapacitated for labour, they are close to

self-supporting.

It was thought that

because he had formerly lived by the buffalo, the Indian would take more

kindly to cattle-raising than to farming as a means of livelihood, but

the early efforts to make him a cattle-raiser were disappointing. The

Indian rather thought that, like the buffalo, the bovine should live

without trouble on the part of man, and that he should be shot

irrespective of the time or the season, whenever appetite suggested the

desirability of a meat supply. Constant effort is, however, now being

rewarded, and the Indian is coming to realize that in cattle-raising, as

in every other avocation, work is essential to success. The live stock

now held by the Indians of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta are

valued at about $1,100,000.

It was difficult to

induce the Indian to till the soil. He would put his hand to the plough

only to quickly withdraw it. When game was plentiful, he would leave the

field for the hunt. The scarcity of game, the pangs of hunger, the

constant urging and teaching of the officials of the Indian Department,

and the example of white farmers, whom the Indians saw grow rich through

agriculture, at length led them to gradually make some use of the land

set aside for them. At the beginning of their farming ventures,

occasional failures so discouraged the Indians that it was difficult to

induce many of them to resume work, and others continued reluctantly the

tillage of the soil without the will which makes labour pleasant and

profitable. Now, however, a fair proportion know the good results that

the earth, notwithstanding occasional drawbacks, will yield to

cultivation, and after failure they return to the tillage of the soil

with hopefulness and energy. There, of course, is still much to be done

before the Indians avail themselves to the full of the splendid

agricultural possibilities of most of their reservations. But the

present results are encouraging. According to the last returns, the

Indians of Manitoba have agricultural implements and vehicles to the

value of upwards of $71,500, the Indians of Saskatchewan to the value of

about $165,500, and those of Alberta to the value of some $141,300. In

the same year the Indians of Manitoba harvested some 83,000 bushels of

grain, the Indians of Saskatchewan 132,000 bushels, and those of Alberta

42,448 bushels. They raised 18,659, 18,649, and 12,353 bushels of

potatoes and other roots respectively.

The Blood Indians, one

of the groups most averse to agriculture, having a reserve in a portion

of southern Alberta, which long was regarded as unsuitable for farming,

have been moved by the success of their white neighbors to assay the

growing of fall wheat. Out of their funds a complete steam plowing

outfit has been purchased, and fifteen Indians have broken 840 acres of

land. 6U0 of which is now under wheat, not in a community farm, but in

individual holdings. They have availed themselves of insurance against

hail, and have evinced an unlooked-for interest in their farming

operations. Last fall these Indians shipped 20 car-loads of wheat, for

which they received $17,SW. The yield per acre went as, high as 45

bushels. Chief Running Antelope, who a few years ago scorned the man who

plowed and sowed and looked to the harvest for return, had from his

grain-growing a cash balance of $1,309 after every debt was paid. One

Indian had a balance of $1,203, and another of $1,200.

Fishing and hunting

still form a considerable means of support, but it grows smaller as

settlement advances. In 1907-1908 the estimated value of- the fishing

and trapping was in Manitoba $51,500 and $72,491; in Saskatchewan

$27,751 and $80,107; in Alberta $5,690 and $17,471.

With respect to the

Tndian population in the Provinces and Territories embraced within the

scope of this paper, various estimates have been formed. The first

official one, which was made in 1871, put the Indian population at

20,998. In 1880 the population was returned at 30,185, and in 1885 at

43,932, inclusive of an estimated population of 11,97S in the territory

inclusive of the Peace River basin and extending to the Arctic, an

estimate which has since been found to be excessive. The last census was

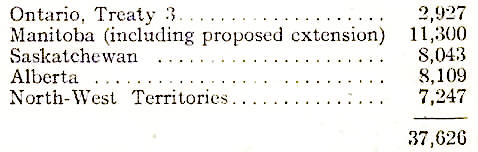

made in 1907, and with some later returns gives the following results:—

Of this number about

28,732 are receiving annuities under treaty. In regard to their tribal

character, these Indians may be approximately classified as follows:—

Crees, 12,249; Saulteaux, 10,826; Blackfeet and their kindred the Bloods

and Peigans, 2,465; Stonies or Assiniboines,924; Sarcees,203; Sioux,

1,029; Chipewyans, Beavers, Slaves, and other tribes of the Athabascan

nation, 7,430; Esquimaux, 2,500. It is practically impossible with the

figures available to form a correct conclusion as to the ratio of

increase or decrease in the Indian population in the West. It can be

safely asserted however that, all things considered, the Indian has not,

as is often stated, rapidly disappeared since coming under Government

control.

Before the extension of

Canada’s Indian policy to the territory acquired from the Hudson’s Bay

Company, and its being policed by the splendid force of the Royal North

West Mounted Police, the Indians were often reduced by famine and

epidemics, with which they were unable to cope; tribal feuds and fights

continued; immorality was rampant, and but little account was taken of

the female portion of the bands. However much it is to be regretted that

even a greater measure of good has not been effected, credit must be

given for what has been achieved, and from what has been done the Indian

Department can with hopefulness look forward to the results which a

continuation of its policy vvill produce. Inter-tribal feuds have

ceased, polygamy •has been practically eliminated, the position of

women, and particularly of female children has been improved, and no

agencies are so potential as the efforts of the missionaries and the

work of our Industrial and Boarding Schools.

It is true that the

pushing of settlement up against many reserves, which until the marked

western development of recent years were practically isolated, has

intensified the strain which sudden contact with the settled conditions

of Canadian civilization put upon the Indian, unprepared by his

environment to readily make use of the advantages, while avoiding the

evils of the new order. The history of the progress ot civilization

shows that it often creates difficulties for those whom it is designed

to benefit before removing the evils which it is intended to cure. Where

not long ago Indian settlements could only be reached by devious trails

or through the bushlands, railways have entered, and in place of scatter

ed Indian dwellings, towns have arisen. With the towns has come the

readier access to intoxicating liquor, so tempting to the red man and so

destructive to all hope of his advancement. One of the greatest problems

has been to find means to adequately cope with drunkenness, which,

despite all effort, increases its baneful influence among many of the

bands. And with every measure of increase in the liquor traffic goes a

proportionate measure of immorality. It is consoling, however, to note

that among a goodly number of the tribes the liquor traffic is gradually

growing less, that groups are now noted for temperance, and that a

healthier moral condition has taken permanent form. It is to be

remembered, in justice to the Indian, that cases of dissoluteness

generally obtrude themselves on the public notice, while virtue quietly

practiced passes unobserved.

Unfortunately

tuberculosis, which is the scourge of the white as well as of the red

man, continues to claim many victims among the aborigines. But the

Indian medical service, hampered though it has been, is producing

beneficial results. There is a notion that the ravages of tuberculosis

are entirely a consequence of the change from the former roving life of

the Indians under tepees to their now more sedentary conditions of

existence and to their life in unsanitary and ill-ventilated dwellings.

As a matter of fact, the Indian was previously a victim of the dire

disease. The Indians, who followed the buffalo generally wintered in

mud-plastered cabins with fiat thatched roofs, with scarcely ever more

than one door, and usually but one window. The only means of ventilation

was the open fireplace made of mud, but this passed away and stoves were

introduced, which the Indian, like the white man, preferred because of

their greater heating capacity. It is just such of those huts as remain

that continue to afford rich breeding grounds for the germs of

tuberculosis; and it cannot be too strongly insisted upon that step by

step with material progress the Indians must be led to provide

themselves with better housing. The Indian himself is beginning to

realize this, and, despite the discouraging ravages still wrought by the

dread disease of tuberculosis, there is reason to look forward to the da}'

when the Indian will be at least as free from this plague as his more

favored white brother. And the reports indicate that improvement in

health as a rule keeps pace with improvement m conditions.

Reference has already

been made to the large expenditure which is being incurred for the

education of the Indians in. Western Canada In Manitoba there are two

industrial, nine boarding schools, and forty-five day schools ; in

Saskatchewan three industrial, thirteen boarding, and nineteen day

schools ; and in Alberta two industrial, nineteen boarding, and nine day

schools. According to the last complete reports there were 1U,308 pupils

enrolled .n the schools, and the average attendance was 6,451. Schools

are grouped into three classes: day schools, boarding schools, and

industrial schools. The day schools are a distinct class. Between the

boarding and industrial schools it is not always easy to draw a clear

line of demarcation, for many of the larger and better equipped boarding

schools provide a measure of industrial training for the pupils. Indeed,

in every case it is insisted upon that as far as possible some manual or

industrial training be given; And in the case of the boarding schools

erected within the last few years at Fort Alexander, Fort Frances, and

Sandy Bay, it was specially arranged that means should be provided for

giving the boys such training as would enable them to take up the

tillage of the soil after they had finished their school course. Day

schools have never been regarded as very effective agencies of Indian

education, and indeed with the small salaries paid it would scarcely be

reasonable to look for any large results. There are points, however, at

which day schools are capable of doing and do effect good.

The work of the

class-room is not allowed to absorb the whole time and attention of the

Indian boys and girls. It is sought to have the hand trained as well as

the head. The girls are taught household duties by taking part in the

regular domestic work of the schools; they learn to cook meat and

vegetables and to bake bread by seeing such cooking done and by helping

thereat. They are taught to care for their clothes, and by example as

well as precept are taught the pleasures as well as the advantages of

cleanliness. They devote some time each week to sewing and mending, and

their handiwork in this direction has been praised by many competent

judges. Every industrial school takes measures to train the boys in

practical agriculture, and in some of the boarding schools there are

farming instructors who teach the rudiments of farming. No attempt is

made to teach scientific farming, for the Indian has not reached a

stage, and must not be expected to for many years, where he can grasp

the significance of the chemistry of the soil. Effort is being confined

to measures designed to make him familiar with the handling of the

plough, and with the sowing and reaping of the grain. Carpentry and

blacksmithing are also taught. It is not, however, aimed as a rule to

give such technical training in these branches as would turn out

finished artisans, but rather to make the Indian boy when he leaves

school competent to do the carpentry work which a handy white farmer

does, and to be able to make the ordinary repairs to implements, wagons,

and harness. Indian boys have in one respect an advantage over the

ordinary boy. As has been already stated, when the treaties were made,

liberal reserves were set aside for the Indians, and now every Indian

boy, when he leaves school has awaiting him an ample area of land, in

most cases very good, and in all cases cultivable, upon which he can at

once settle and make a home.

Each year seems to make

the Indian more amenable to the restrictions of school life, and more

ready to benefit by the advantages afforded. Indeed, the children were

not at any time most to blame, for, apart from scattered individual

cases, they seemed to appreciate what was being done for them. Many of

the parents, however, suspicious of the new order and preferring to have

their children grow up like unto themselves, often induced boys and

girls, who had been placed in the schools, to desert, or in their

intercourse with them so worked upon their minds as to make school life

seem irksome, and rendered the children restive of discipline.

It would be invidious

to make comparison among the several schools. The standing of each can

be pretty correctly gauged from the particular reports which are

published by the Department. An unbiased reading of these reports leads

to the conclusion that it would be difficult to find more effective

agencies for the uplifting of the Indian and the placing of him

eventually in the position of a self-supporting citizen of the country.

It is only about one-third of a century since the principal treaties

were made with the Indians of the plains. Though this term is a large

proportion of man’s allotted span, yet it is but a short period in the

evolution of a race. It is a question whether in the history of

aboriginal tribes the world over, such progress towards civilization can

be shewn in the same space of time as is indicated by the foregoing

statistics. It has taken many centuries to bring the barbarians of

Europe up to their present state of enlightenment; and though industrial

and other education, the bath-tub and the flesh brush cannot make a

red-man white, yet it has been amply proved that he is capable in a very

few centuries of becoming the equal of his pale-faced brother. |