|

Canadian Pacific Railway

Company.

TRANSPORTATION has been

a serious problem in Canada from the beginning, as was necessarily the

case in a country of such enormous area. In early times, when France was

in possession, the immigrant followed the rivers. First of all, however,

he crossed the Atlantic in vessels of 200 to 400 tons, the voyage

lasting two or three months, with scurvy or typhus usually raging on

board. On entering the St. Lawrence the ships anchored at nightfall; the

charts of the river were imperfect, and there were no lights, except

here and there a kettle of blazing pine-knots hung on a tree outside a

King’s post. If he did not join the fur-traders, the new settler began

clearing the forest in some seigniory, for a feudal land tenure, based

on the Custom of Paris, existed down to 1854. As may be seen to this

day, the French Canadian farms were very narrow and very long, this mode

of subdivision giving every holder a frontage on the river, bringing the

people closer together, brightening their social life and affording them

better protection against the Iroquois. The St. Lawrence and its

affluents were the channels of such primitive trade as was carried on in

the interior. Commercial intercourse with the British and Dutch Colonies

to the south was prohibited, although many a package of beaver was

conveyed down Lake Champlain or the Kennebec and bartered for English

goods. Vessels built at Quebec with the aid of bounties, carried lumber

and flour to the French West Indies and Acadia, but the chief export

trade, that in peltries, was done with Franco.

In those times the

maritime nations of Europe were seeking a short route to Asia. Jacques

Cartier, Champlain. and many others supposed from what the Indians told

them that, if they sailed up the St. Lawrence to the middle of the

Continent, they would meet waters flowing the other way, down which they

could sail into the Oriental seas. So sure were they that this would

turn out to be the true North-West passage, that when some of them got

to Laehine, a few miles west of Montreal, they fancied they were on the

high road to China and accordingly gave it that name. Two centuries

later it has become possible to reach China via Canada, not, however, by

the St. Lawrence, but by rail as tar as Vancouver. Although France has

lost her North American Empire, the names of her missionaries and

explorers will live forever in the history of the Continent. They

discovered the Mississippi, Lake Superior and the Red River of the

North; established posts where Chicago, Detroit and other Western

American cities now stand, for, as one of them said, they had a

remarkable instinct for good situations, and did much then, and later,

for the Canadian North-West. We owe not a little to those intrepid men,

who sallied forth into the wilderness with 110 selfish motives, but with

the object of extending the King’s dominions and promoting the glory of

God.

When the colonisation

of Upper Canada commenced under British rule, the immigrant in his

Western journey still followed the water routes, for there were as yet

no roads. The canoe or Durham boat containing his worldly effects had to

be dragged by oxen through forty miles of rapids between Montreal and

Kingston, or, where that was impossible, portages had to be made through

the forest. The cost of procuring fresh supplies and of shipping produce

to market was enormously enhanced by the difficulties of moving them up

and down rivers in their natural condition. It soot: became apparent

that, if the country was to make any substantial progress, it would be

necessary to build canals at various points on the St. Lawrence and its

principal tributaries. The local advisers of the Imperial Government

favoured the project, and, though they may have attached more importance

to its military than to its commercial aspect, Canadians are greatly

indebted to them for the impulse they gave and the substantial aid they

furnished to the movement. Between 1820 and 1850 the main rivers were

tolerably well equipped with canals, locks and dams, most of which have

since been enlarged, to meet the growth of traffic. The Lachine Canal

was the first to be built, but the most important was the Welland. Many

of the United Empire Loyalists who came to Canada at the close of the

American Revolution, entered by way of Niagara, and gradually pushed

their settlements into the Western Peninsula of the Province. Their

surplus supplies could not be conveyed to Montreal within a shorter

period than six weeks to two months. (It may be interesting to recall

that the ocean rate on general merchandise from Liverpool to Montreal

was £1. 2. per ton. while for the next 400 miles westward, by the St.

Lawrence, it was £6. 12. 9.) The Peninsula was extremely fertile, and

whole colonies of settlers were flocking in from the United Kingdom. But

unless a canal were cut through Canadian soil from Lake Erie to Lake

Ontario, a distance of 27 miles, to overcome the obstacle to navigation

presented by the Falls of Niagara, it was clear that its trade with

England would be diverted from the St. Lawrence route to the Erie Canal

and the Port of New. York, a state of affars which might entail serious

political consequences. The construction of the Welland canal saved the

situation, and it soon became a formidable competitor to the Erie canal

for the traffic of the Western States.

Such in a few words,

was the origin of the Canadian canal system. The canals on the St.

Lawrence from Montreal to Lake Erie are, all told, 70 miles in length.

Those on the Ottawa, Rideau and Richelieu rivers and Lake Champlain are

not so long. It is not easy to ascertain the first cost of these canals,

but the total expenditure on their construction, reconstruction and

upkeep, together with that on inland harbours, has exceeded

$100,000,000. Tolls were abolished some years ago. In the United Kingdom

the canals were built by private capital, and some have passed under the

control of the railways. The construction of the Welland canal was

undertaken by private capital, but, fortunately for us and fortunately

too for the shareholders, the company had to abandon the project. All

our canals without exception are now owned and operated by the Dominion

Government For seven months of the year they render good service in

keeping down rail rates, besides transporting a considerable tonnage of

the bulkier kinds of freight. The “all-water route” from the head of

Lake Superior by the Welland canal to Montreal usually determines the

rate on wheat from the Canadian West to the seaboard, just as the Erie

canal does for grain from Buffalo to New York.

The ‘‘all-water route"

via the St. Lawrence has not, however, altogether fulfilled its earlier

expectations. It obtained a large share of the traffic of the Western

States thirty or forty years ago when the wheat-belt of the continent

lay round Lake Erie and Lake Michigan, and the grain was carried East by

small sailing vessels, which traversed the Welland and lower canals at

their leisure and had nothing to fear from the railways of the day. Such

conditions no longer prevail. The wheat-belt has extended to the

Canadian North-West, Minnesota and the Dakotas, and the present output

there and elsewhere, in the West is far in excess of the output of

former times. There are now 40,000,000 people in the States bordering on

or served by the Great Lakes. An immense traffic has arisen between Lake

Superior and Lake Erie, the former sending down wheat, iron ore, lumber,

and other commodities, and taking back coal and general merchandise.

Before the recent depression, over 50,000,000 tons of freight , valued

at $550,000,000, passed through the locks at the Soo in a single season,

that of 190f). The Welland and St. Lawrence canals have a depth of 14

feet, whereas between Lake Erie and Lake Superior there is a 20 or

21-foot channel, which has en abled the United States companies to

create a vast fleet of steam vessels, most of which are beyond the

capacity of the Welland. Although Canadian vessels are excluded from the

inland or coasting trade of the United States, our own fleet on the

Upper Lakes is growing rapidly; but many of our vessels are also too

large for this canal. Some carry wheat to the Lake Erie end of it and

“lighter,’ ’since boats carrying more than 75,000 bushels cannot get

through without “lightering,” whilst the larger vessels sail to Georgian

Bay ports, transfer their cargo to the elevators, and steam back to Fort

William or Port Arthur. The grain is transported from the elevators by

Canadian railways to the ocean steamers at Montreal. In like manner,

United States steam vessels, of which many are of the tonnage of a

modern ocean steamer, run from Duluth and Chicago to Buffalo, and turn

over their grain, not to the Erie canal any longer, but to the railways,

which haul it to New York, Boston, or Baltimore. Finally, a great deal

of grain, from Canada and the United States, is now carried to the

seaboard from the place of production in the West by “all-rail.” This

has been rendered possible by the improvement of road-beds and the

employment of more powerful locomotives and more capacious cars. When

business on the Upper Lakes is slack, as was the case recently, Canadian

vessel owners on our “all water route,” reduce the rates to Montreal to

so low a figure that a deluge of United States export grain goes to that

port, with the result that protests are heard from New York. A natural

water-way such as that of the St. Lawrence can never become a negligible

factor in transportation. It is worth noting, also, that the Canadian “

water-and-rail” routes to Montreal are, or can be made, considerably

shorter than the United States “water-and-rail" route to New York. Our

Georgian Bay ports are much nearer Duluth and Chicago than Buffalo is,

while the rail journey from them to Montreal by a new branch of the

Canadian Pacific Railway will be 80 miles less than that from Buffalo to

New York

The State of New York

is enlarging the Erie canal to allow of its admitting 1,000-ton barges,

and various canal schemes of a more ambitious character are talked of in

the United States. The Canadian Government contemplates deepening the

Welland canal. This, however. would not be of much avail unless the

canals below Prescott were also deepened. Meanwhile the Georgian Bay

Canal project, estimated to cost $100,000,000, is receiving support in

various quarters, notably from the districts where the money would be

spent. Whatever the next few years may bring forth, the Cana; dian

people will make any reasonable sacrifice to ensure the transport of

Canadian traffic by Canadian routes. Manifestly it is their interest to

do so. The old Roman said that no estimate could be formed of the future

wealth of a district that possessed fifteen miles of olives and vines.

But what shall be said of the future of a region like the Canadian West,

which, with a present population of a million, has still 250,000,000

acres of black loam uncultivated? In another generation it will contain

more people than all the rest of Canada, and in time to come, probably

more than there are to-day in the Three Kingdoms. The possibilities of

the West are so great that one can hardly exaggerate the importance of

adopting a liberal policy, which shall retain the traffic all the way

from the wheat-field to Europe in Canadian and British channels.

No sooner had the early

canals been completed than it became necessary to undertake the

construction of railways in Upper and Lower Canada. The canals had

developed in some degree the basins of the rivers and lakes. The

introduction of the locomotive enabled settlers not only to enter Upper

and Lower Canada, but to pass into the vaster regions beyond. Our

neighbours in the United States began to build railways in 1830. and,

private capital being scarce, the Federal, State and Municipal

Governments, during the next forty years, voted liberal aid in money,

land and guarantees. Canada followed their example, and, in proportion

to population and resources, carried that form of paternalism to a

greater length. The Imperial Government gave initial assistance by

guaranteeing a loan of $7,500,000. Canada’s credit in England was not

good, for, after one or two local railways had been built, a rebellion

broke out over the question of Responsible Government. Moreover the

abandonment by England of the policy of Protection, which included the

preferential treatment of Colonial exports, dislocated our trade for a

time. One of the first railway surveys was that carried out by Captain

Yule of the Royal Engineers, who laid down a line between Quebec and St.

Andrew’s, in New Brunswick, through territory belonging at that time to

the British Crown. Unhappily, in 1842, the Ashburton Treaty —Lord

Palmerston styled it the Ashburton Capitulation-—deprived Canada of the

Aroostook District, brought the northern boundaryof the State of Maine

to within a few miles of the St. Lawrence, and, when the time came for

building the Intercolonial Railway, necessitated a circuitous route to

Halifax and St. John At first the Canadian Parliament was disposed to

establish Government ownership of railways, owing to the difficulty of

enlisting private capital; but British money was found for the

construction of the Grand Trunk, and Government ownership remained in

abeyance for a time.

The history of the

Grand Trunk Railway is well known in England and Canada. The original

prospectus, issued in 1853, promised a return of 11>2 per cent, per

annum on the share capital, besides the stated interest on the bonds.

Canada and Canadians were blamed for the misfortunes of the road, but

soma of these were unavoidable. There was in England and another in

Canada, but as the actual control was exercised from London, 3,000 miles

away, it is not surprising that there was a good deal of waste in

construction. The cost of bringing in materials for a pioneer road was

excessive in those days, and the Canadian Government did not grant as

much financial assistance to the enterprise as had been expected. Before

the line was completed the panic of 1857 occurred. Wheat, which during

the Crimean War of 1854-56 had realised $2.50 per bushel at Toronto,

dropped to half that figure, and there was a tremendous collapse in land

values. Immigration fell off and remained at a low ebb for a long time,

the Western and North-Western States, with their free prairie

homesteads, being more attractive, even to the native Canadian, than the

bush lands of Canada. The original line of the Grand Trunk was fairly

well constructed, but the small, wood-burning locomotives and light iron

rails were badly fitted for the Canadian winter. Subsequently the

Canadian Board became involved in politics. In 1862 the General Manager

stated in a letter to the Government that the cost of the original line

had been .£12,000,000 sterling, of which the Canadian Government had

subscribed over £3,000,000. He added, however, that the company had

afterwards been forced by political pressure to spend probably more than

£3,000,000 “ in constructing parts of the system, which, though of

benefit to Canada, are, commercially, entirely worthless and only drags

upon the paying portions of the railway.” Parliament blundered in fixing

upon a gauge of 5 feet 6 inches, when most of the United States roads

had a gauge of 4 feet 8^2 inches. As a consequence of this through

traffic had to be transferred from one car to another at the

international frontier. This was a painful chapter of railway history,

and, in consequence, Canadian credit suffered in England for years.

Portland in Maine was selected as the winter terminus, simply because

there was no access by rail to the Canadian ports of St. John and

Halifax, and, by the Ashburton Award the short all-British route to them

had been lost. It may be added that it was the Ashburton Award which,

years afterwards, obliged the Canadian Pacific to cut across Maine on

its journey to St. John rather than follow the longer route on British

soil; and it is owing to the Ashburton Award that the Grand Trunk

Pacific is unable to reduce the distance between Quebec and Moncton, as

traversed by the Intercolonial, by more than 30 miles. If, as a recent

English writer puts it, “both the Canadian Pacific and the Grand Trunk

proper desert the British flag shortly after leaving Montreal for the

Atlantic seaboard in winter,” it is only fair to indicate on whose

shoulders the responsibility really lies.

The east - and - west

direction of Canadian lines is imposed on them by the configuration of

the country, and, in some measure, it may be suspected, by the American

tariff, which taxes all Canadian products bound south save those going

in bond. The Grand Trunk was carried east and west that it might serve

the settled districts in the St. Lawrence Valley, and connect Chicago

and the Western States with Montreal and Portland. The Intercolonial

joins the cities on the St, Lawrence to. the ports of the Maritime

Provinces, and hence could not run otherwise than east and west, whilst

the Canadian Pacific was built as a national work expressly to connect

the newer Provinces in the West with the older ones in the East. At the

present time United States roads are running spurs from south to north

into the Canadian North-West and British Columbia for the purpose of

diverting traffic to United States ports, but so far they have not

accomplished much. In his famous report of 1S39, Lord Durham recommended

the establishment of the bonding privilege between Canada and the United

States, which' was brought about some years later. Railway traffic in

both countries is left free to follow the most economical route. Goods

for Canadian use reach Canada from Europe by New York or Boston; a

portion of the surplus grain and package freight of the Western States

is shipped to Europe by way of Montreal; the Canadian Pacific takes

products of the Pacific States to the Atlantic or to New England, and,

contrariwise, carries New England wares to the Pacific States; while

American railways handle shipments from Eastern to Western Canada. All

this intercommunication goes on without interference from the Customs

officers on either side of the boundary, who merely see that the bonded

cars are properly sealed. When this arrangement—excellent for both

countries— grew up about 1855, it was predicted that henceforth Canadian

roads would all run from north to south in. order to meet the American

roads at the boundary, but the prophecy was not fulfilled. At that time

there was reciprocity of trade with the United States to the extent of a

free interchange of natural products. The treaty was abrogated by

Congress in 1866, and Canada forthwith set about building up trade with

the United Kingdom through the use of Canadian railways and Canadian

ports, which involved the carrying of Canadian produce from west to east

and of British golds from east to west. The heavy American tariff on

Canadian productions has fired us with the ambition to be commercially

as well as politically independent of the United States, and has

contributed as much as any other single agency to our recent closer

union with Britain.

After the Grand Trunk

came the Intercolonial, which, viewed as an experiment in Government

ownership and operation, has been disappointing. True, the road is

handicapped by its roundabout route and by being exposed to water

competition at almost every point. Its rates in general are low, its

special rates on Nova Scotia iron and steel bound west being probably

less than cost of haul; while the bulk of its local traffic consists of

coal, lumber and other rough commodities in the transportation of which

there is little profit. The capital account now stands at 887,500,000,

and no interest has ever been paid upon it. The system is 1,450 miles

long. The Government has also 267 miles of road in Prince Edward Island,

making over 1,700 miles in all under its control. The Island line has

never paid operating expenses; its capital account is $8,000,000. On

both roads politics play a vicious part, and the Government, in despair,

is contemplating their lease to a company railway or the transfer of the

management to a commission.

After the Intercolonial,

the Canadian Pacific was constructed. The construction of a line from

the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean had been the dream of enthusiasts for

years, but did not take bodily form till British Columbia and the

North-West were admitted into Confederation. The Federal Government

tried its hand at building the road, but in 1881 made a contract with

the present Company, which completed the work. Instead ,of dwelling on

the success of the Canadian Pacific Company, a word may be said on the

development of the West. Burke, in one of his speeches on the American

Colonies, spoke of their export of a few thousand quarters of

breadstuffs to England as the splendid act of “this child of your old

age, which, with a true filial piety, with a Roman charity, has put the

full breast of its youthful exuberance to the mouth of its exhausted

parent.” At that time the American Colonies had been settled for more

than a century. This year, with an average harvest, the Canadian West,

which really was not opened till the completion of the Canadian Pacific

24 years ago, will export, principally to England, not less than

15,000,000 quarters of wheat, to say nothing of other grains, and

probably 150,000 head of cattle. In 18S8 the City of Winnipeg received

and transmitted by rail 110,000 tons of goods. In 1908 the total

exceeded 2,500,000. This takes no account of the traffic in grain and

other articles passing through Winnipeg en route to other points east

and west, but relates solely to the trade and manufactures of Winnipeg

itself. In 1889 the traffic on the Central division of the Canadian

Pacific, which extends from Lake Superior to Swift Current, through the

larger portion of the wheat-belt, was less than 350,000 tons, whereas

last year it exceeded 10,000,000. Before the Canadian Pacific was built

it cost six shillings, in English money, to transport a bushel of wheat

from Winnipeg to Liverpool. Now it costs nine-pence, although the haul

by rail, the Great Lakes and the Atlantic, is 4,500 miles long. The

Canadian Pacific has over 5,000 miles of completed road in the West, and

the Canadian Northern, Great Northern, and Grand Trunk Pacific about

2,000 more. In the older districts no farmer is situated more than 12 or

15 miles from a railway. Man for man, the mileage is greater than in

Minnesota, Dakota, or any other portion of the United States; and rates

on wheat and other commodities are as low or lower than those to and

from corresponding American points.

This incomparable

region is receiving 150,000 immi grants a year even in these

comparatively dull times, the number from the United States, who came in

1908, exceeding 60,000. Since 1898, when the rush from the United States

began in earnest, neighbours in the South have invested $ 300,000,000 in

lands, stores, mines, cattle-ranches, lumbering and elevators in the

Provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. British Columbia is also becoming

populated, although it must be borne in mind that its area is enormous,

Its coal, gold-copper and silver-lead mines are prospering, its lumber

trade has grown to formidable proportions, and its fisheries are the

richest in Canada, the annual catch being now worth more than that of

Nova Scotia. Fruit-growing is becoming an important industry, and, when

Vancouver Island is properly settled, is likely to expand to great

dimensions. The Canadian Northern Railway has a large mileage west of

Lake Superior, and some day, no doubt, will reach both oceans. The Grand

Trunk Pacific will soon have to be added to the list of transcontinental

railroads. The Government is building the section, 1,800 miles long,

between Moncton in New Brunswick, and Winnipeg, and will lease it to the

Company, while the Company is constructing from Winnipeg westward to

Prince Rupert on the Pacific coast. It has been recently stated in

England that a controlling interest in the Canadian Pacific is held in

the United States. As a matter of fact such holdings of Canadian Pacific

securities are very small indeed, the bulk being owned in England,

Germany and Holland

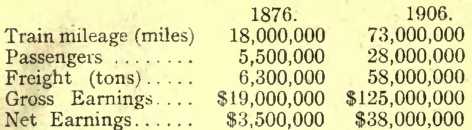

The earliest statistics

of railway operations in Canada go back to 1875, and a few figures may

be given to show the progress made since that date, premising that the

mileage increased from 5,0U0 in 1876 to 21,000 in 1906. In 1908 it was

23,000:—

It will be agreed, that

is a very satisfactory advance in the space of 31) years. The progress

made by the railways from 1900 to 1906 was so remarkable as to lead one

of our public men to declare that if the Nineteenth Century belonged to

the United States, the Twentieth belongs to Canada. The aggregate

capital cost uf Canadian railways down to 1908, counting the subsidies

granted by the Federal, Provincial and Municipal authorities, and the

expenditure on Government railroads, has been $1,600,000,000 ; and, in

addition, land grants have been voted to the total amount of 50,000,000

acres. So far the railways, as a whole, have not yielded any large

return to the investor. The net earnings in 1908 were only sufficient to

pay a dividend of 3.20 per cent on the stock and bond issues of the

company roads. The lines built and operated by the Government yielded

nothing. A better condition of things may be looked for as population

increases and the extensive natural resources are turned to account

Synchronising with the

development of the railroads, it became necessary to deepen the St.

Lawrence between Quebec and Montreal. This work has occupied 60 years.

The depth of water at the shallowest part was, in the earlier days of

navigation, 11 feet Ocean vessels bound for Montreal had to be

“lightered” at Quebec, while those outward-bound from Montreal loaded

only a portion of' their cargo, the remainder being taken to Quebec in

tow-barges. A uniform depth of 30 feet has now been obtained throughout

the 170 miles of river, and the channel has b^en widened. The cost of

this undertaking has been about $10, U00,000,and the quantity of

material removed by the dredges amounts to 45,000,000 cubic yards. The

result is that Montreal, which is 1,000 miles from the open Atlantic,

250 from salt water and 80 above the nearest tidal influence, has been

transformed into a port capable of accommodating all but the very

largest ocean vessels. We are vain enough to think that this work is in

a measure comparable to the deepening of the Clyde from Greenock to

Glasgow. The Allan Company began carrying the mails between England and

Canada in 185G, and in the intervening half-century has rendered

splendid service The Imperial Government has paid a postal subsidy to

the Cunard Line almost uninterruptedly since 1840, but has paid nothing

to the Allans or to any other Canadian steamship line operating on the

Atlantic, beyond the mere sea postage collected on mail matter 'going

from England to Canada. Long ago the Canadian Government felt some

jealousy that Britain should help the Cunard Line whoss vessels sail to

New York, rather than the Allans, who were doing so much for the St.

Lawrence trade. This seeming neglect may, however, have been a blessing

in disguise. At any rate, thrown upon our own resources, we have

succeeded in dissipating the bad name of the St. Lawrence route among

navigators and insurance men, and in making Montreal one of the chief

ports of North America. Its ocean-going tonnage, in and out, in 1908 was

4,000,000 ton. The Canadian Pacific “Empresses” and the Allan turbine

steamers, which now carry the mails, are among the finest vessels

afloat. The contrast between them and the tiny, high-pooped barks of

Jacques Cartier’s day sums up the progress of ship-building in the last

300 years. Ocean freight rates from Montreal are as low as those from

New York and Boston. Steamers conveying perishable articles are

furnished with an admirable system of cold storage, which is under

Government supervision, while the moderate temperature of the northern

route, in summer, attracts shipments of meats from United States. The

ocean traffic from St. John is growing rapidly, and Quebec, though for

the present eclipsed by Montreal, will some day become the great port of

the St. Lawrence, Since 1867, when Confederation took place, the total

tonnage of sea-going shipping entered and cleared at Canadian ports,,

has risen from 4,000,000 to 17,000,000 tons register.

The Imperialist who

wishes to traverse the Empire can now travel continuosly under the

British flag. The Canadian Pacific and Allan steamships will convey him

from England to Halifax, St. John, Quebec or Montreal, whence he may

journey across the continent by a Canadian Pacific express train to

Vancouver. Here he finds “All-Red” steamers sailing to Japan and Hong

Kong, whence he may proceed in other “All-Red” vessels to India or South

Africa, or may travel back to England through the Suez Canal.

In conclusion, it is

manifest that Canada has made up her mind to be true to herself and yet

to remain affectionately attached to Britain. An American poet tells of

the little flower which guided the hunter on the plains:—

“See how its leaves all

point to the north, as true as the magnet—

“It is the compass

flower, that the finger of God has suspended "Here on its fragile stalk,

to direct the traveller’s journey

“Over the sea-like,

pathless, limitless waste ot the desert.”

And an English writer,

commenting on these lines, has expressed himself in terms with which, I

am sure, the great majority of the people of Canada agree:—-“So it must

be with all Canadians. Their hearts, differ as men may on political or

social or religious questions, are true to their North-Land—a land of

great rivers and inland seas, of illimitable prairies and lofty

mountains, of rich sea-pastures and luxuriant wheatfields—a land of free

government and free speech—a goodly heritage with which they can never

part to & foreign Power.” |