|

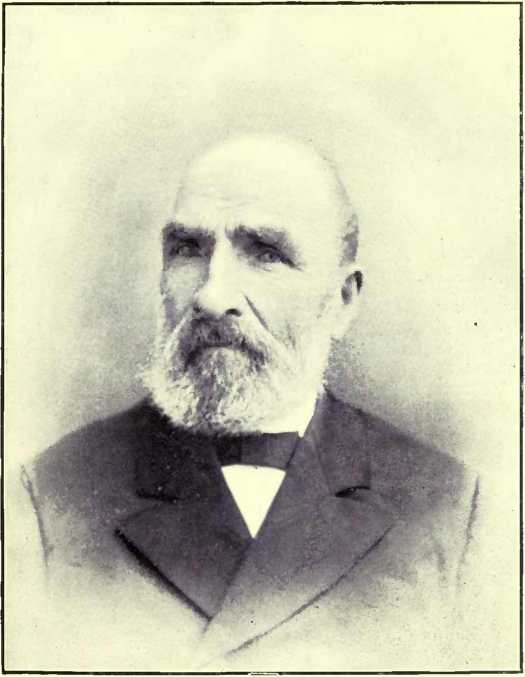

DAYID CATHCART, the

subject of the following sketch, was born in Port-na-Bleigh, County

Fermanagh, Ireland, on the eve of the 5th of November, 1805, which makes

him at the present time ninety-three years of age. The family appears to

be a branch of the Cathcarts of the west of Scotland, who, at the time

of the colonization of the north of Ireland by James I., emigrated to

that country and settled in the County of Fermanagh. They were a

military family, the Scotch branch of which attained high rank in the

British army—notably Major-General Lord Cathcart, whose exploits during

the Crimean War brought such lustre to the British arms. During the

American war of 1812 some of them fought for the old flag, and at its

close settled in the eastern part of the province, in the County of

Carlton, named after one of the early governors of Canada, and who was

also related to the Cathcarts. Mr. Cathcart was the son of a farmer, and

as such was early initiated into the details of farm management. His

education in comparison with ours of the present day was necessarily

limited, but appeared to be the best his country could afford, and was

quite sufficient for his purpose in after life when he had raised

himself to a position

DAVID CATHCART

of honor and trust in

the country of his adoption. At the age of eighteen he enlisted in the

yeoman cavalry of the county. His connection with the militia in that

corps extended from his enlistment at eighteen until he left the country

for Canada, in 1842, at which time he held the rank of sergeant. The

yeomen were considered then, and are now, a very important link in the

service, and were recruited entirely from land owners and land holders

of the county and their sons. Mr. Cathcart, at the age of eighteen,

entered the ranks at the earliest time he could be admitted to the

somewhat distinguished position of being a Yeoman of the county. His

life during the period from eighteen to twenty-eight was passed in the

manner in which the average farmer passes his time, sowing and reaping,

going to markets and fairs, caring for stock, and regulating the affairs

of the state.

At the age of

twenty-eight he married Margaret Creighton, sister of the late James

Creighton, of the base line, and who afterwards settled on the next lot

to Mr. Cathcart, on concession 6, Blanshard. This union was a happy one,

and it is safe to say that a kinder, more contented and jovial pair

never linked their fortunes to fight the great battle of life. Mr.

Cathcart was bluff, honest, not very demonstrative in success, nor

apparently much crest-fallen in misfortune ; and they had, as is the

common lot of all, their share of both. Mrs. Cathcart was affectionate,

extremely affable and lively ; she was a kind mother, a tidy

housekeeper, and had a heart as sympathetic and warm as ever beat in a

woman’s bosom. She was the average size, well made, and was sprightly

and full of mirth up till near the time of her death. Even during the

last years of her life, when suffering from perhaps the severest

affliction that can befall humanity (the loss of her sight), she still

appeared happy and was never heard to complain. She had unbounded

confidence in David, as she always called him, and her countenance

seemed to express the deepest anxiety in her dark days, as she appeared

to strain her sightless eyes when his friends called on him, to see that

they were suitably entertained. She died in the year 1882. After his

marriage he began farming on a small farm of his own, and followed that

business until he left his native isle with his family, to seek a new

home for himself and them in the wilds of Western Canada.

LEAVES OLD IRELAND

An important crisis in

his life was now at hand. In the year 1824, John Galt, the Ayrshire

novelist, and Captain Dunlop, otherwise known as Tiger Dunlop in the

Nodes Ambrosiana, and later of the town of Goderich, Upper Canada, had

associated themselves with a number of other gentlemen and organized

what is known as the Canada Company. A large portion of Western Canada

at that period was a complete wilderness. This company obtained from the

Crown a grant of a large and fertile section bordering on Lake Huron,

and extending easterly and known as the Huron Tract. The greater part of

this domain was at once surveyed and offered to actual settlers. Agents

were sent everywhere in the old land extolling the salubrity of the

climate, the fertility of the soil, and pointing out, as agents only

can, that in those pathless wilds any person who would might soon make a

fortune and a home.

Mr. Cathcart had

reached that period of life when men delight in adventure and action.

His family were growing up around him, and his native Ireland had no

grand offerings to give for industry or enterprise. It was hopeless to

look for fortune in a land which fortune seemed to have deserted

forever. Out of a people who were all poor it was hardly possible for a

man ever to get rich. He knew that to get independence he must go where

independence was to be got. It did not take him long to decide. The die

was soon cast, and May, 1842, saw him leave old Ireland with all his

household goods for the new land in the West. After an uneventful voyage

of four weeks and two days he arrived at Montreal.

REACHES BLANSHARD

The paternal care of

the Canadian government in those early days did not extend to the poor

immigrant with that tender solicitude and protecting care that it does

now-a-days. There was no provision made for their comfort, nor anyone to

give advice. Every person did the best he could and shifted for himself.

If he got safely through the hands of designing scoundrels and cheats,

who were always in wait at the port of debarkation, so far so good. If

he was unwary and got fleeced out of his little store of money, well, he

should have taken better care of himself. He was a stranger in a strange

land, and was a fair mark for unprincipled operators. Mr. Cathcart was

very fortunate on his arrival in meeting Mr. McDonald, who had

previously completed the survey of the township of Blanshard, which was

the best and the last surveyed township in the Huron Tract. From the

description of the lands in Blanshard, given by Mr. McDonald, Mr.

Cathcart decided at once to go there and seek a home.

When he reached Toronto

the only means of getting up into the western country was by means of

hiring teams and plodding on through a region much of which was nearly a

wilderness. But onward they came, and on a pleasant evening in the

beginning of July reached the township which was to be their future

home. Night setting in, they pushed on to Little Falls, or what is now

St. Marys, expecting to find shelter till next day. In this they were

disappointed. St. Marys was composed of only a few houses, the occupants

of which seemed to be no better oif than themselves. They could not buy

food, for no one had any to sell. It was fortunate that he had a good

supply in the wagons, or the whole family would have gone supperless to

bed. Still they pushed on out along Queen Street, past Skinner’s Corner,

where I believe James McKay, of St. Marys, had then located, —past the

old Shoebottom place, where one Cameron then lived, and through the

unbroken wilderness for several miles, until he reached the object of

his hopes, and he stood on the farm which was to be his home so long as

he was able for active life. This was lot 18, in concession 6, of

Blanshard.

THOSE EARLY DAYS

The change from the

green hills of Old Ireland to the inhospitable wilds of Western Canada

was very great indeed. The separation from old associations and from

friends, never more to meet on this side of eternity, had a most

depressing effect. The altars at which they had worshipped and the

little plot where the ashes of their fathers reposed were far away.

Communications with those left behind were few, and could not be

expected in less than three or four months. Neighbors were few and far

between. This will be easily understood when the townships of Blanshard,

Downie, and Fullarton, at the time Mr. Cathcart came in, only contained

one hundred and twenty-three homes. For miles on every side stretched a

silent and unbroken wilderness. The old settlers were brave men indeed,

and must have had boundless hope in the future of the country ever to

brave the trials and hardships of pioneer life. Under the most favorable

circumstances they could look forward to nothing but years of hardship

and toil. They were the champions of progress, and laid the foundation

of a civilization which is the glory of the Canadian people.

But even under all

these adverse circumstances they were not without enjoyment. The

consciousness that the piece of earth on which they labored would one

day be their own, gave them renewed energy for their daily task. Every

day saw something done, and some long-looked-for end accomplished. What

though they had to work hard ? What though the remuneration was small

and slow in coming ? Come it undoubtedly would I and it was something

worth striving for to be the lord of a hundred acres of fertile Canadian

soil. And then, too, when the long winter nights had come, what pleasant

hours were spent in those old shanties in the woods! A great back-log

like a tree was carried in and thrown on the fire, which roared and

crackled in the old clay fire-place like a lime-kiln, and sent a shower

of sparks up around the smoky lug-pole, like a furnace. If the storm

raged without, there was happiness within. The presence of a neighbor

gave zest to their pleasure, as they talked of the Old Land, the green

fields of Ireland, or the heather hills of Scotland, until their hearts

were full, and their eyes suffused with tears. After all, those were

happy days; we shall never see their like again.

From 1842 to 1855 Mr.

Cathcart, like the other pioneers, had employment in clearing his farm,

erecting buildings, and putting it in shape generally; and beyond having

two or three trips to Goderich on the jury (the only place where court

was held in the Huron Tract) did not take a very prominent part in

public affairs.

ENTERS PUBLIC LIFE

In the year 1850 the

township of Blanshard was separated from Downie, this being the year of

the introduction of the Municipal Act. The late T. B. Guest was the

first reeve, and held the position till 1853, when he was succeeded by

the late Arundell Hill in 1854. In 1855 Mr. Hill was again elected

reeve, and we find that David Cathcart was elected deputy. In 1856 David

Cathcart was elected reeve. He was again placed in that office in 1857,

1858, and 1859. In 1860 the late John Dunnell was reeve, and David

Cathcart deputy. He then retired from public life till 1869, when, after

a most spirited contest, he defeated Mr. James Dinsmore. He was again

elected in 1870, and again in 1871, when he resigned and accepted the

office of treasurer of the municipality, which position he held for

several years. Time was now beginning to tell on him and his energy was

not what it had been. The affliction that overtook his wife somewhat

unmanned him, and her death in 1882 bore on him with crushing effect. He

resigned the office of treasurer, which was the last public position he

held. His friends entertained him at a public dinner, at which many of

the prominent men of Blanshard and surrounding districts took part.

BLANSHARD GRAVEL ROADS

During the period of

his first official connection with the township he took an active part

in the scheme of building the London and Proof Line gravel road. This

road extended from the Stone Bridge on Queen Street, St. Marys, passing

through Prospect Hill, to the Proof Line in London Township ; and of

this he was inspector for four years. He was also instrumental in

building the Base Line road, extending from Shoebottom’s corner to the

village of Woodham. We can understand the magnitude and utility of these

improvements when we consider the state of the roads throughout the

municipality—mud and corduroy everywhere. The idea of gravelling all the

roads in the township by statute labor had not been thought of then, nor

for many years after. It seems surprising that when there was so much

diversity of opinion on his gravel road schemes, and particularly in

locating the Base Line road (and in this case he met the most determined

opposition), he still retained the confidence of the people.

Between 1860 and 1869

the progress of the township had been rapid. Gravel roads made by

statute labor were now almost everywhere. Farmers going to market no

longer drove on the Base Line or London and Proof line gravel roads

where they had t o pay toll, when they had made roads themselves which

were as good. As a consequence an agitation was at once begun to buy the

roads in Blanshard from the companies, take off the toll-gates, and keep

them in repair from the township funds. This agitation led to the

struggle between Mr. Cathcart and Mr. James Dinsmore in 1869. Mr.

Cathcart was elected, and at once bought all the stock in the London and

Proof Line gravel road (except what was held by the county, which was

given to the township free) and at once removed the toll-gates off this

road. The conduct of Mr. Cathcart in this transaction led to most

important and far-reaching results a few years later, under the

reeveship of Mr. James Dinsmore. The Base Line road was bought by Mr.

David Brethour when he occupied the reeve’s chair in 1873, when the last

toll-gate was removed.

TRAINING DAY

The first time we ever

saw Mr. Cathcart was on what was known as training day—the twenty-fourth

day of May, 1860. A short description of this ridiculous obligation of

Canadian citizenship imposed on them by the government may not be

uninteresting.

The militia at that

period was organized on an entirely different basis from what it is at

the present. All ablebodied men between the ages of twenty-one and sixty

years had to attend at a certain point and receive instructions in the

art of war one day in the year. For this purpose the loyal and patriotic

Canadians had selected the twenty-fourth of May, Her Majesty’s birthday.

An officer of the force, a few days previous, had sent out orders to all

the men liable to bear arms to muster on the flats at St. Marys and

perform their annual drill. That day we remember well. It was beautiful

but exceedingly hot. Horses were few, and most of the men made the

journey on foot, many of them walking ten or twelve miles through the

woods and over dusty roads to the place of rendezvous.

Groups of strong, able,

happy fellows could be seen wending their way along the concession lines

and through forests, then one mass of foliage, to the place of meeting.

On nearing the London and Proof Line gravel road, which crosses at right

angles the various concession lines, the spirits of the pedestrians

seemed to rise in proportion as the distance decreased to the various

places of refreshment which were located on that oldest thoroughfare in

the township, there being no fewer than six or seven hotels between

Prospect Hill and St. Marys. Considering the great heat, the fatigue of

the journey, and the importance of the duties of the day, it is not

surprising that the potations at the various hostleries were frequent

and copious. This produced an exhilaration of spirits in some, which, by

the time we reached St. Marys, had passed the hilarious stage of

excitement and was fast merging into the uproarious. On reaching the old

bridge over the Thames on Queen Street, we noticed that a large

concourse of people had assembled on the flats, and the various

evolutions of the troops were about to begin.

On all the leading

roads converging into the town, travel-stained and dusty men were

pouring in.

On crossing the bridge

over the mill race, opposite the planing mill, as we entered the flats,

several of the officers were chatting. All were on foot except one, who,

we were informed, was Colonel Sparling, the officer in command. He was

mounted on a feeble steed, over whose venerable head there appeared to

have passed the snows since George III. was king. It was like all

mortality, fearfully and wonderfully made. A heavy ration of straw in

the winter, followed by a soft ration of grass in the spring, had

increased the abdominal region out of all proportion to the other parts

of its organism. On this ancient specimen sat Colonel Sparling, the

commander-in-chief, and whose short, thick-set limbs stuck straight out

on each side like the arms of a capstan. The Colonel appeared to give no

orders to any of his officers, but surveyed the field in quiet dignity.

At last our name was

called by an officer at some distance on the flats, and we at once

proceeded to fall into the ranks. This officer was a middle-aged, nimble

looking man of average size, his head well set back, large chest and

full heart, and a pair of limbs that suggested strength, activity, and

the greatest powers of endurance. He appeared to be the only officer

that knew anything at all about military terms or mana3uvres, and, as a

matter of course, directed the men through the various drills. This was

Mr. Cathcart. Another officer stood near him who, we were informed, was

Lieutenant James Dinsmore. The experience that Mr. Cathcart had gained

in the yeomanry in Ireland stood him now in good stead. In Enniskillen,

in Armagh, and in Londonderry, bodies of British troops were always

stationed, at whose drill he had often been a spectator, if not a

participant, which gave him a knowledge of military terms, as well as

some of the simpler movements practised in the regular army.

We were at last ordered

to fall into line. Our left rested at the bridge, near the Colonel, and

our right extended up to and parallel with the mill race. A more motley

and awkward line of warriors one could hardly conceive. We had not the

smart uniforms our volunteers are at present privileged to wear. Every

one of us was dressed as seemed right in his own eyes. Some of the North

of Ireland men had plug hats, bought in Donegal or Londonderry, with

black broadcloth coats, made clawhammer fashion, garnished and

ornamented with rows of brass buttons in front and at the peaks of the

tails in rear. Others, less pretentious, had encased themselves in blue

cotton goods, wearing the ordinary straw hats, while one gentleman had

heavy winter garments, and his pericranium covered with a high crowned

hat, amply ornamented with squirrel tails. But though we were uncouth

and awkward, let no man for a moment think that in that thin, awkward

line there was nothing but clowns. In the faces of those men were deep,

thoughtful lines, evidences of strong character. Many of them never knew

fear. Possessed of sturdy independence, determined and resolute, they

had braved the dangers and possibilities of a long voyage across the

sea, and with a heroism that cannot be overpraised, struck into the

interminable forest and hewed out for themselves independence and a

home. If Mr. Cath-cart were to stand on the spot to-day on which he

stood on that 24th of May, and call the roll again, how many of those

jovial fellows could respond to their names? Alas! how many? Perhaps a

half dozen. Nearly all are gone. Some have left and found homes

elsewhere, but by far the greatest number have answered the roll call of

a greater commander than Mr. Cathcart, and joined the silent ranks of

the great majority.

A LUDICROUS INCIDENT

At length the order was

given, “Attention! Stand at ease!” and for the next hour or two we

wheeled, we marched and countermarched, shouldered arms, grounded arms,

and performed many intricate movements, which must have convinced the

spectators, if the opportunity offered, that we were the lads that could

show them how fields were won.

Hitherto we had been

executing the simpler movements, when the order was given by Mr.

Cathcart for the most difficult manoeuvre of the day. This was to effect

a change of front. Our left rested at the bridge over the mill race,

where the Colonel still maintained his position, and our right at a

stump near the Sarnia Bridge, the line being parallel with the race. Our

right was ordered to swing around and take a position at right angles to

that which it had before. Precautions were taken to guide the troops

through this movement as orderly as possible. At a short distance from

the stump on which our right rested, a barrel had been set up as a mark

to guide the advancing column, and farther on still Lieutenant Dinsmore

was stationed as the point at which our right should rest, having

described about one-fourth of a circle. We accordingly began to move,

but before we had gone very far it was painfully evident that we were

not going to be successful; indeed we had got into the greatest

confusion, which was heightened by an incident on our left. A soldier,

then residing on the 10th con. of Blanshard, and who was somewhat of a

wag in his day, had gathered some grass and quietly fastened it to one

of the brass buttons of the claw-hammer coat which we have already

mentioned. In the course of the last movement the innocent wearer of the

garment had to pass close to the Colonel’s steed, which no doubt thought

that the grass was intended as a peace-offering for its usual ration,

and reached out and seized it. In doing so it unfortunately caught the

button at the same time and held on. This led to most disastrous

results. A hungry horse at one end, a swearing Irishman at the other,

the piece de resistance the tail of a claw-hammer coat. The issue was

not long in doubt. The coat tail gave way, and so forever was destroyed

the mercantile value of a coat which the knights of the needle had

admired as the triumph of the art. The fun arising out of this incident

abruptly brought the duties of the day to a close, and Mr. Cathcart,

seeing the state of affairs and the attitude of some of the troops

around the Colonel, proposed three cheers for the Queen, which were

loyally given. He also informed the men that he had ordered refreshments

for all who were in the ranks. This was followed by prolonged cheering,

to which that given for Her Majesty was but a trifle.

CHARACTER AND APPEARANCE

Mr. Cathcart in

personal appearance was an excellent representation of an old country

squire, the fine old country gentleman, all of the olden time. He was

robust looking, strongly built, and his face in every lineament

expressed open-heartedness, kindness, and generosity. No more generous

person ever lived. That was a trait in his character no one could appeal

to in vain, and, as might be expected, he was often victimized by

cunning and designing suppliants. He was even tempered and good natured,

although if exasperated beyond a certain point, particularly if unfairly

accused of a mean or dishonest action, his resentment was sudden and

emphatic, and usually had the effect of moderating the statements of his

opponent. Blanshard never had, perhaps, a public man who enjoyed more

the confidence of the people throughout his whole public career than did

Mr. Cathcart. He had not obtained this good-will by pandering to any

party or clique, as most politicians usually do. Neither did he know the

art of blazoning the failings and short-comings of his opponents

continually before the people and religiously keeping back any good

qualities they might possess, and thereby raising himself into

prominence on the wreck and ruin of other men’s reputations. His

position as a public man was particularly his own, and arose from that

noble appreciation by all men of genuine honesty and integrity of heart.

As a public speaker he was not more than average, but what he did say

was clear, forcible, and to the point. As an illustration of this, on

one occasion when a political contest was being held previous to a

parliamentary election, one of the candidates made a long speech, at the

close of which an elector jumped up and said that two minutes from

Cathcart would have had more effect than all his long harangue. He has

been a life-long and uncompromising Conservative, but is neither blatant

nor offensive in advocacy of those principles which he believed were for

the best interest of his adopted country. He has always been a

consistent supporter of the Methodist Church, although he has never

taken a very prominent part in the management of ecclesiastical affairs.

He was not pharasaical in his mode of living, and did not occupy the

highest seat in the synagogue, thanking God that he was not as other men

are. He never preached religion—he did better, he lived it.

Mr. Cathcart might, if

he had been desirous, have had a much larger share of this world’s goods

; but saving money was not his forte. Indeed had he come to this country

with a fortune it is doubtful if he would have kept it. The whole

disposition of the man was clearly against the hoarding of money. His

kindly, social feeling prompted him to spend freely ; and during nearly

a half century of active life I have never known that he at any time had

recourse to harsh measures for the collection of a debt.

His tastes were simple.

About his work on the farm, he was very methodical. In his intercourse

with men he was affable and kind. Nothing gave him so much pleasure as

to have his friends and neighbors share his hospitality. Away back in

the forties, when the township about where he lived was a wilderness,

many a poor, hungry family found food and shelter in his shanty for the

night. He was always amply rewarded in such cases by the happiness

suffusing the 7 hearts of the poor pioneers when they left in the

morning to pursue their way through the dark forest to some quiet,

lonely spot, there to make a home. He was always neat in his attire, but

never gaudy. His manner was simplicity itself. Affectation he had none ;

what he appeared to be he was in reality. He was fond of a good horse,

and, as a natural consequence, took considerable pride in driving a fine

animal.

The old gentleman has

long since passed the allotted span of three score years and ten; nay,

he has long passed that period which some by reason of mere strength are

said to attain. Those men with whom he labored are nearly all gone, and

he stands, at the age of ninety-three years, all alone, a relic of the

past generation.

Mr. Cathcart had a

family of nine, of whom three are deceased. James died in Ireland;

Helen, (Mrs. Bobier) in Blanshard; and Frances Ann, (Mrs. Pratt) in

Winnipeg. The surviving members are Henry, residing on the 8th

concession Blanshard; Catherine, (Mrs. Somerville) of Brussels ;

Elizabeth, (Mrs. Bobier) in Manitoba; David, in British Columbia;

Margaret, (Mrs. St. John) St. Marys; and John W., of the Garnet House,

St. Marys. |