|

IN every age men and

women have been given to the world, the phases of whose character have

been of a nature so heroic and transcendent as to challenge the

admiration of succeeding generations. It is certainly indicative of

goodness among men, that the pure, the unselfish and the philanthropic

command our highest esteem, and, by universal consent, these names are

written on the scroll of fame as being worthy of our emulation. We

instinctively gather around such characters, and if we do not stoop to

hero worship, we accord them a place in our affections, separate and

distinct from the great mass of mankind. By our conduct in cherishing a

warm remembrance of their actions, we furnish the most positive proof of

our belief that they have done something towards lifting to a higher

plane our common humanity. No one can look at the life of Howard without

being permeated to some extent by the far-reaching sympathy of one who

spent a life and a fortune to improve the condition of the unfortunate

and the helpless in the prisons of Europe. Lying under the ban though

they were, for offences against the laws of their country, still they

were human, and the expiation of their crimes by the loss of their

liberty too often ended in the loss of their lives. But he alone stood

up in their behalf, and the world is better that he lived.

The

ever-to-be-remembered story of Grace Darling exhibits a phase of

character which could only have been the growth of the purest

unselfishness and the warmest devotion to the duty she conceived to he

owing to her fellow-creatures.

On the 6th day of

September, 1838, a terrific storm was raging over the Farne Islands. The

sea was running mountains high in mad tumultuousness around the

lighthouse where she resided, and rushing on in foaming fury, was dashed

into fragments on the beetling cliffs along the shore. Through the

darkness of that terrible night, and above the roar of the waters, she

heard the despairing cry for help from the hopeless crew of the

ill-fated ship Forfar that lay a sinking wreck at the mercy of the

waves. At daybreak she saw at the distance of about a mile the perishing

crew still clinging to the wreck.

She thought not of the

stormy sea ; she thought not of the danger among the white capped waves

; she thought not of home where she might have remained secure; she

thought only of the perishing sailors, and launching her boat she

proceeded to the rescue, and brought them to a place of safety. We love

to dwell on such intrepid actions as these, but at the same time we

should not forget that in every stage of society men have been born with

perhaps as wide sympathy as Howard, and women with as dauntless courage

as Grace Darling. Men and women all move in a little world of their own,

and we venture to say that before the three-score is reached (no matter

in what sphere our lot has been cast) many things have come under our

observation which could only spring from great hearts full of kindness

and consideration for their fellowmen.

There is perhaps no

condition of existence in this country where the heroic qualities and

feelings of sympathy could find greater scope than in the lives of the

early settlers. The difficulties arising from their situation had the

effect of developing the best traits in their character. The

inconveniences to which they were subjected were common to all. Their

isolations and their hardships formed amongst them a strong bond of

union, and wherever sympathy and help was required, sympathy and help

was always freely given. That spirit of rivalry which obtains at the

present did not exist in the early days of Blanshard pioneers. Wher all

were poor, no feeling of envy could be stirred up by contrast with those

who were rich. The straggle in which they were engaged and their

helpless condition cemented together the families that were scattered

here and there in the forest. Rude and unpolished in their manners they

may have been, but there was that within them which served as a basis on

which has been raised our present civilization. It is gratifying to know

that some of those men who fought the battle of life in the early days

have had their labors crowned with success, and are spending the evening

of life in comfort and a well-earned rest.

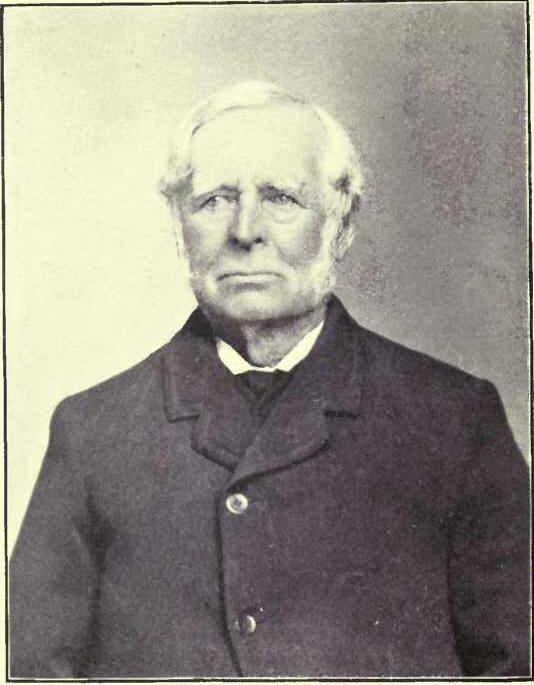

Of the few that are

remaining of the original settlers (there are not more than ten or

twelve now alive in the township) is Mr. Samuel Radcliff, on lot 25, in

the 10th concession of Blanshard. Mr. Radcliff, the subject of the

present sketch, was born in Castlemillan, near Belfast, County Down,

Ireland, in December, 1820. The family was originally from Cumberland,

on the borders of England, and emigrated to Ireland along with large

numbers of the Scotch, under the colonization scheme of James I. Like

the greater portion of the settlers from the north of Ireland, he was

the son of a farmer. Unlike, however, the bulk of his countrymen who

came to Canada about that time and settled in the Huron Tract, the

family was in comparatively good circumstances. His education was

somewhat limited. The means for obtaining an education in Ireland at

that time, and indeed up to recent date, were not of a high order. The

teacher was usually some old man whom the course of nature had rendered

unfit for physical labor. In his youth he had been taught to read and

write a little, and when strength had failed he earned a little money by

teaching, to keep starvation from the door. His pupils were supposed to

pay sixpence or a shilling a month for his services. This sum had to be

supplemented still further by every scholar bringing with him so much

turf every morning to keep the cabin where school was kept warm during

the day. During a visit to Ireland a few years ago, the writer visited

one of these seats of learning in the County of Tyrone. It was a small,

low building, used for a dwelling-house and a school. On entering the

little cabin you stepped down nearly a foot to the clay floor, which,

from the tramping of little feet, was worn into holes. Here and there we

could see patches that had recently been renewed by fresh clay. At one

end a great turf fire was blazing, not in a chimney, for the school

contained no such convenience, having simply a hole in the roof that

served the two-fold purpose of letting down the rain and letting out the

smoke. A few benches placed around the walls composed the whole outfit

for teaching the jToung idea how to shoot. An old lady was sitting by

the fire smoking a very short black pipe. After a few minutes

conversation we left. As we departed we left the old lady a souvenir of

our visit, when she curtsied -very low, saying at the same time, “ Grod

bless your honor; may you have many happy days,”—the first and the last

blessing we ever received.

COMING TO BLANSHARD

At a similar seminary

to the one described, Mr. Radcliff received his education. From the time

he left school until he was twenty-two he worked with his father on the

farm. Indeed he might have remained there, as the holding was a large

one, but the life of an Irish farmer did not very well suit the ideas of

a person of his energy and determination. The Huron Tract was being

opened up at this time by the Canada Company, and it was more in accord

with his adventurous spirit to come to Canada and make a home for

himself, than to remain at his ease in his native land. At the age of

twenty-two he decided to make the venture, and sailed from Belfast on

April the 16th, 1842. His voyage to Quebec was, upon the whole,

uneventful, but they experienced such stormy weather that on more than

one occasion they thought they would have been lost. At the end of eight

weeks of buffeting on the stormy Atlantic they arrived in safety. On his

arrival he at once sought and obtained work, at which he stayed for one

year. But the eastern part of the province was not to his taste. He

heard of the more favored country in the west, around what was then

known as New London, and determined to push his fortune in that

locality. Accordingly, early in 1844, he came west and reached London.

He obtained employment here, at which he remained four years. During the

few years he labored in the township of London, he gained experience

which he found of great advantage in after life when he had a farm of

his own. The duties in connection with the clearing of a new farm are so

entirely unlike the methods in the old settlements, that a year or two

contiguous to a new country is of great advantage to a new settler. This

Mr. Radcliff soon found. He had learned to use the axe effectively, the

most important tool on a new farm. He had also served his apprenticeship

at driving oxen, in which duty he was considered the most proficient in

the section of the country where he lived. It may seem strange to those

not acquainted with the clearing of land, that any one man could excel

another in the simple duty of driving a pair of oxen; but the old

pioneers knew well that a good or bad ox teamster in a logging field

meant success or defeat to the men who were rolling. Mr. Radcliff soon

found that the greatest power with oxen, as with men, lay in kindness. A

teamster who continually abused his cattle was considered very stupid,

and always succeeded in making his team as stupid as himself. Mr.

Radcliff’s qualities as a teamster were soon found out, and he

experienced at loggings no difficulty in always having the most expert

gang to follow him. During the years he had been in the country he had

steady employment, and being of a thrifty and saving disposition, had

saved a large portion of his wages. The township of Blanshard, as it has

been stated elsewhere, had been surveyed and thrown open for settlement

in 1841, and was being rapidly taken up. With his little savings he

decided at once to become a pioneer of the township and make for himself

a home in the new country. In February, 1848, or 51 years ago, he

selected lot 25, in the 10th concession, which from that day until the

present has been his home. Not a tree had been cut on the farm ; the

roads had not been cut out except in small patches, and there they were

blocked with the refuse of fallen timber that rendered them impassable.

There were neither schools nor churches, and the whole section around

him may almost literally be said to have been unbroken forest. The Hays

family had preceded him, and made little openings here and there, in the

midst of which, little shanties seemed to have dropped down amongst

stumps, logs, and brush. Having thus located a farm, his next duty was

to select a suitable place for his house and proceed to its erection. As

there were no pumps or wells in those days, a site for a shanty was,

wherever possible, chosen near where water could be obtained. The

erection of the building itself, although a matter of considerable

labor, was not attended with much difficulty to those early settlers,

who could do almost anything with the axe. The style of the building was

simplicity itself, and the architect who first formulated the plans for

a backwoods shanty must have had an extraordinary foresight into the

adaptability of his plans to the circumstances. Out of the many

structures erected in Blanshard and surrounding townships fifty or sixty

years ago, we never knew one to deviate in the slightest degree from the

original. Buildings of this kind were constructed throughout without a

single nail or piece of iron in any form whatever. When a new settler

wanted to raise a house, he asked a few of the nearest neighbors for

assistance, and the structure was completed, as far as the walls were

concerned, in one day. This consisted of the four sides of great logs

laid at right angles to each other at the corners. If the roof was to be

one of troughs, then the front part was made one log higher than the

rear, thus giving a slight angle to the roof towards the rear of the

building. A hole was cut out in front for a door and window, the window

rarely containing more than four lights. The door and the hinges, and

the floor, were all made with the axe by the settler, and were taken

from white basswood, split and made into thin plank. The roof was also

made from basswood trees split in the centre and scooped out with the

axe. These were laid across the walls, the lower ones with the hollow

part upwards and the upper ones with the hollow part downwards. The

seams of the walls were then filled with chinking, over which was laid a

good covering of clay, both inside the building and on the outside,

when, with the exception of the chimney, the castle of the Canadian lord

of the soil was complete. In those days the modern stove had not been

invented, and the chimney was a part of the building of great

importance. It was constructed of stone at the base, and up as far as

the great beam, which served as the mantel, where, from its front to the

rear, was placed the lug-pole. From the lug-pole to the top of the roof

and a little beyond was built with clay and wood split into narrow

pieces and laid at right angles to form a vent. The fireplace was of

wide dimensions, and in the winter was kept constantly piled with great

logs, which lighted up the whole inside of the house. From the lug-pole

dangled a chain and hooks, where the pots were hung on the blazing fire.

The bread was baked in the bake-kettle on the hearth. A portion of the

hot coals were raked out on the hearth, on which the bake-kettle was

placed containing the bread, the lid put on and a further portion of hot

coals placed on that, with a still further supply of hot coals gathered

around the side ; and there the patient and hard-working wife of the

settler made the bread for her husband and family.

THE PIONEER HOME

In those log houses and

similar dwellings have been born, and there played in youthful

innocence, many of Canada’s greatest and most gifted men. Rude though

they were, and humble, the associations of the old log house are still

dear to many, although removed far from them.

If happiness consists

in a consciousness of duty faithfully done in the years that are past,

in thankfulness and contentment with the present, and a holy and abiding

hope of the future, the subject of this sketch is triply blessed from

having a high appreciation of all the three. We deem it one of the

grandest dispensations of heaven that true happiness is not peculiar to

any age, position, or place in society. How often it eludes the grasp of

the rich and the great, and flying away finds a resting place in homes

of the poor and in the humble dwelling of the backwoods settler. The

remembrances that still cling to the old log house, the long, weary

struggle with the world, and the final triumph over their difficulties,

still fill the hearts of the few old pioneers that remain. Time, that

has made a desolation of all their aspirations for the future, still has

left them happy memories of the scenes that can return no more. If these

old decayed and rotting walls have been the shelter of sorrowing ones,

they have also been the home of exceeding great joy. In the long winter

nights, when the storm was raging without, the snow driving across the

dreary waste and piling up great drifts around the doors, the old

pioneer with the “big Bible,” once his father’s pride, laid on his knee,

would raise his heart in thankfulness to heaven in the voice of Psalms,

and simple songs of praise, till the old log house seemed like a

paradise in the forest.

From this time forward

Mr. Radcliff assumed the responsibilities and had to face the

difficulties and trials of a new settler. On the 9th day of December,

1847, he married Elizabeth Hedley, a sister of Roger Hedley, of the town

of St. Marys, and in the month of February following he brought his

young wife into the log dwelling he had recently completed. This lady

was born in London Township, her parents being from Northumberland in

England. From her parents she learned and always spoke with a strong

Northumberland accent. She was a kind and motherly woman, and entirely

devoted to her husband and family. For over fifty years they fought the

battle of life together, and saw their children grow up around them as

respectable and good citizens of their native country. There were born

to them ten of a family, all of whom are alive except one,—Helen, who

died at the age of 13 years.

Those remaining are

Robert, on the old homestead; David, a merchant in Toronto; James, C. P.

R. ticket agent, Toronto; Samuel, practising medicine in the North-west;

Allan, in the North-west; John, in the West; Mary Ann, in Chicago;

Elizabeth, in Chicago; and Jane, with her father in Blanshard. Mr.

Radcliff is a man of strong Presbyterian proclivities—in fact a better

specimen of the old Presbyterian would be difficult to find. Eirm and

determined in his religious principles, bordering even on dogmatism, he

never gives much attention or takes much concern in the affairs of other

denominations. His early training at the fireside of his father had left

a lasting impression on his mind. His manner of thought on all matters

pertaining to theology was based and formed intensely on the rules and

injunctions laid down in the Confession of Faith and the Shorter

Catechism. On these lines he trained his family. He was strict in the

government of his household, and his children knew well that any duties

he imposed upon them had better be attended to, otherwise it might be

unpleasant for themselves. It is gratifying to him, however, now to know

that his efforts for their good have been amply rewarded, as all of them

are doing well and are a credit to him as well as to themselves.

EARLY REMINISCENCES

As he was now settled

in life, he at once set to work to improve his farm by cutting down the

timber and preparing a fallow for next summer. In the spring he

succeeded in clearing a couple of acres which he sowed with wheat so

that he might have bread for the next year. Sugar and molasses were

plentiful; so were potatoes, but bread was quite another thing. In a new

country the obtaining of bread was one of the greatest difficulties the

new settler had to contend with. When he was able to raise a little

wheat he had to carry it frequently many miles to get it ground.

Potatoes were plentiful, and with beech nuts lying everywhere his pigs

soon got so fat they were hardly able to move, although beech-nut pork

was not the kind that would tempt the palate of an epicure. Still it was

pork, and backwoodsmen did not draw very nice distinctions as to the

quality of the fare set before them. When a man has no choice of food it

is wonderful how his taste becomes relaxed. In the harvest he reaped

from his little plot of wheat sufficient to supply the family till next

year’s crop would be ready. To supply his immediate wants he had to

thresh with a flail a couple of bags, the little stock of flour in the

settlement being exhausted. It was the custom among the old settlers to

give a share of everything to their neighbors as long as it lasted. If

any one of them had a bag of flour the settlement would not be in want.

In getting the two bags of wheat ground a supply would be obtained and

the wolf kept from the door. But how was he to get it to the mill ?—and

thereby hangs a tale indicative of the terrible inconvenience attending

the life of a poor settler in the backwoods. He had nothing but a sled,

and the mill was sixteen miles away, at Carlyle, in the township of

Williams. A neighbor living three-and-a-half miles farther up the

concession had an ox-cart which he determined to hire and take his wheat

to the mill. He accordingly walked up and succeeded in effecting an

arrangement for the ox-cart. In making the journey there and back he

travelled seven miles. He took oxen and got the cart, travelling seven

miles more. His trip to the mill took two days and was sixteen miles

each way, or thirty-two miles in all. He returned the cart to the owner,

adding another seven miles. In going to do one day’s work with his oxen,

as the payment for the hire of the cart, he travelled another seven

miles; so that in getting his two bags of wheat to the mill he travelled

sixty miles and spent three days’ labor with himself and oxen. On

another occasion he started with the oxen and sled to St. Marys with a

small grist, when, after a long pull through the mud, he reached the

river where a bridge of timber had been erected, only to find it gone,

the whole structure except one stringer having been carried away the

night previous by a freshet. The water was still very high, but

necessity has no law, and flour he had to have. He took his oxen from

the sled and chained them to a stump, and getting a bag on his back,

started to walk across the stringer over the river. This he accomplished

in safety, backwards and forwards, till the whole was across. After it

was ground the whole was again carried on his back to the sled on the

other side of the river, when he again turned for home, which he reached

after having been nearly twenty-four hours in making a trip of less than

six miles each way. On another occasion the neighbors had borrowed flour

from each other until all the stocks in sight were completely exhausted.

One of them, however, had a bag of wheat, but had neither oxen nor cart

to get to the mill. A settler on the eighth concession had been able to

get a wagon, which was accordingly rented for the trip, and another

journey of fifty miles made with a single bag of wheat. But this state

of things did not last long with Mr. Radcliff. He had saved up his

ashes, and, boiling it into potash, started for London with his oxen and

sled, where he got as much for his potash as bought a new ox-cart, the

first vehicle he ever owned, and came back to Blanshard feeling that he

was a rather prosperous man.

BURIAL IN THE EARLY DAYS

“She was a lonely woman

and left none to mourn.”

We must now relate a

mournful event which exemplifies in another direction the hardships of

the pioneer. As life necessarily implies death, so, wherever we have

life, death is always hovering near to claim its dole from mortality. In

this case the work of the destroyer was not glossed over with those

attentions and decorations which the bereaved love to place around the

mortal remains of the departed. There were no tinsel or bright

cerements, no flowers heaped on the corpse, which in their lovely beauty

appear to destroy to some extent the awful aspect of death. Around the

body there were no aching hearts, no sighs, no tears, no minister to

point out to the fewT that came to the burial that mortality would put

on immortality, and that the life here was simply probationary to the

life beyond the grave. But the body had to be laid in its last resting

place, and it was horrifying to think that it should be consigned to its

kindred dust without a coffin. Mr. Radcliff, whose mind revolted at such

a condition of things, wrenched off a few boards from the inside of the

house, and out of this material, with the aid of another neighbor,

constructed a rude receptacle in which to place the body. It appears

somewhat ludicrous, however, when we consider his anxiety that this rude

coffin should be constructed in proper form. Not having any tools better

than the axe, he found it almost impossible to give the proper shape at

the point where the shoulders would rest. To overcome this difficulty, a

quantity of water was heated to the boiling point, in which he placed

the ends of the boards for the sides, when, after they had become

softened, he placed the ends between two logs and bent them to the

desired shape. The bottom being ready, he nailed them on and kept them

in position. Into this rough box the body was laid, with a pillow of

straw under its head. When the time for interment had come, he presented

himself with the oxen and sled, and having placed the coffin in the

sled, fastened it with a chain so that it could not shake off in the

journey. So the little cortege moved on and wended its way through the

woods to the burial plot where McIntyre’s church now stands. The scene

was most impressive in its simplicity. There was no service at the home

they left; there was no service at the grave. When the chain that held

the coffin to the sled was unbound, a few of the strong men lifted it in

silence, lowered it to its last resting-place, and filling in the earth

left to its quiet sleep all that was mortal of what was once a human

being. When we contrast the present state of things with those of fifty

years ago, which we have described, the change appears great indeed. All

that human ingenuity can accomplish, all that wealth can buy, are

brought into service now to disguise as much as possible the ghastly

aspect of death. The flowers, the subdued light of the apartment, the

solemn look and the soft motions of the watchers around the beautiful

casket, are all evidences of the love and tenderness of those who are

still on this side of eternity. When we contrast the splendor of the

hearse and the sombre drapings of the horses with the oxen and sled, and

the long line of carriages that follow the departed one, to show their

last respects, with the few hard-handed men that accompanied the sled

through the wroods, we can scarcely realize that only a half century has

passed.

KILLED AT A BARN-RAISING

Another event of a

melancholy kind that occurred shortly after Mr. Radcliff came to the

township, and in which he was closely concerned, ought to be noticed. In

the early settlement the buildings on the farms were wholly built of

logs. The erection of the log buildings, especially barns, which were

raised to a great height, was a dangerous operation. When we consider

that some of these barns had from sixteen to eighteen rounds of great

logs piled one on top of another, it will be seen that those placed at

the highest elevation must have required great skill and care to put

them there without accident. The skids were always placed near the

corners, and the men on the ground who manipulated the “muleys” kept

them as near the outside of the skid as possible. If one end of the log

was pushed up a little beyond the other it would be sure to slip from

the skid and come to the ground, endangering the lives of many men. That

more accidents did not occur certainly arose from chance rather than

from the care of the hands. The grog boss at raisings was always on hand

with a supply of the “elevater,” and at the end of the day, when the

building was high and required steadiness, quite a number of the men had

become reckless from the frequency and depth of their potations. On one

of these occasions, at a raising on the next farm to Mr. Radcliff’s, a

log slipped from the skid and, falling to the ground, killed the

proprietor of the building. The feelings of the poor wife may be

imagined when the dead husband was carried into the shanty. As she could

be of 110 service around the dead body, Mr. Radcliff asked her to his

home for the evening, which invitation she accepted. During the night he

was awakened by the moaning and shouts of the poor woman, who appeared

to be walking backwards and forwards in the darkness. When he made a

light he saw at once the heart-broken creature had become mad. One of

her little boys coming into the room, she flew at him with the fury of a

lion and would have torn him in pieces. For the remainder of the night

he had to watch and hold her from doing the family injury. When the

morning came, which was Sunday, and the settlers not moving out early,

he dared not leave to get assistance. As a last resource he pushed the

demented woman outside and held her in his arms, shouting at the top of

his voice. The late Robert Somerville, who lived on the next farm, heard

his cries and at once went to help him. Other neighbors came in and

relieved him from his trying position. He kept her in his house for

several days until means were found to place her in an asylum. It is

pleasing to know that she afterwards recovered, but still retained the

memory of all she had done during the period of her frenzy. Two other

settlers were killed soon after at barn-raisings, which had such effect

on him that forever after he allowed no liquor on the farm, and he has

the honor of being the first settler in this section to have raised his

building without whiskey.

WOLVES AND BEARS

The roads in the

township in the early days were simply horrible, and it was almost as

much as a man’s life was worth to make a trip over them for a few miles.

At that time potash was the only product of the farm for which money

could be obtained, and as a consequence nearly all the settlers made

more or less of that commodity. On one occasion he went to St. Marys

with a barrel in the ox-sled for Mr. Edward Long, the present respected

treasurer of St. Marys, who shipped nearly all of that class of goods

brought into town. He pulled along fairly well until he reached Silver

Creek, when he found the mud so deep that he nearly lost himself, oxen,

sled, and the potash. But if the mud was bad, the corduroy was, if

possible, worse. The inventor of corduroy must certainly have been in

league with the evil one, as such a road could only have been introduced

by the great enemy of mankind. We believe we are safe in saying that a

ride of half a mile over a piece of new made corduroy would be

punishment sufficient for any offence that a man might commit against

society.

Wild animals, too, if

not numerous, were still represented, particularly wolves and bears, and

at night could be heard howling around the little dwellings in the

woods. On a pleasant evening in the summer, at dusk, Mr. Radcliff,

having occasion to go to the door, heard a poor porker set up a most

unearthly squealing in the woods near Fish Creek. A bear whose larder

had been somewhat depleted had formed the plan of replenishing it with a

piece of beech-nut pork, and carried off the poor animal bodily. A trio

of Nimrods composed of the late John Slack, William Slack, and Mr. Hunt,

determined to secure bruin the next evening if he came back to increase

his supply. But to enable them to secure the bear, they very discreetly

made arrangements to secure themselves. Accordingly they erected a

scaffold, on which all three of the hunters mounted, with guns charged

to the muzzle, and kept watch during the night. Whether his bearship was

not in love with beech-nut pork, or whether he considered the supply

ample for his immediate wants, history sayeth not. At all events he did

not make his appearance, and the hunters, after long watching, returned

to their homes with their game-bags empty.

Blanshard at this time

had no churches and few schools. A log school-house had been built at

the corner on the tenth concession, where worship was held on Sabbath

days by the different denominations. The Bev. Mr. Skinner made

occasional visits to the Presbyterian families located near by, and

preached in the old log school, administering the rites of baptism to

the children, and in which place several of Mr. Radcliff’s children were

baptized. He was always in favor of free schools, and during his

residence in the township has contributed to the erection of five. At

this corner was opened the first post office in the township, outside of

St. Marys, which was kept by the late Mr. Bell as post master. The

village of Prospect Hill was not then in existence, and the first hotel

was opened in that village by Robert Shaw.

SCHOOLS AND CHURCHES

During his long career

he never neglected his duties to the church to which he belonged, and

supported her schemes as far as it lay in his power. Some forty years

ago he, with Mr. Forsyth, Mr. Hamilton, the late T. D. Hamilton, and

others, erected a Presbyterian church near the lower end of the tenth

concession. In this congregation he was chosen as elder, and continued

to hold that honored position until the church was removed. In 1866 the

Rev. Robert Hall, who was pastor, resigned the charges of Granton and

Fish Creek, as the church at the tenth was called, and devoted his whole

attention to the churches in Nissouri. A call was then extended to the

Rev. Allan Finlay, who ministered to both churches, Granton and Fish

Creek, when, after a few years, the Fish Creek congregation was broken

up, a portion going to Granton and a portion to Nissouri. Mr. Radcliff

then joined the Granton Church, where, during the pastorate of the Rev.

David Mann, he was again chosen elder. Previous to the organization of

the church named, he sought church privileges in the town of St. Marys,

to which place he walked for several years, the greater part of the way

through the woods.

Mr. Radcliff’s

instincts were of a purely domestic character, and he never sought

public place or position. With the exception of four years that he sat

on the board of directors of the B. M. F. I. Co., he never held public

office. His care and attention were devoted to the management of his

farm and the furtherance of the interests of his family. He took an

active part in the promotion of the scheme for building the Proof Line

gravel road, and always gave a helping hand to any plan for the

furtherance of improvements which were for the good of the people. In

politics he was a Reformer, and was not at all shy in the advocacy of

the principles of that party. In his dealings with men he was strictly

honorable, and was liberal enough to concede a point where positive

evidence could not be obtained to the contrary. Although not a

teetotaller, he has been temperate through his whole life. He was always

industrious and paid close attention to his own business, in which

course of conduct he has been amply rewarded with a competence for his

old age. He was not at all excitable, but firm and decided in his

character, not particularly fond of show, and moderate in his tastes and

desires. In business he was cautious and shrewd, and could not be easily

swayed either to one side or the other. He was never what might be

called a strong, robust man, though he has always been in the enjoyment

of good health. The snows of nearly eighty winters, however, have not

passed over him without leaving some trace, and the loss of his partner,

who had stood by him for over fifty years, leaves him alone, so to

speak, in the world. He is still hale and hearty, and it seems that many

years may yet pass away ere he will be called on to pass the bourne from

which no traveller ever returns. |