|

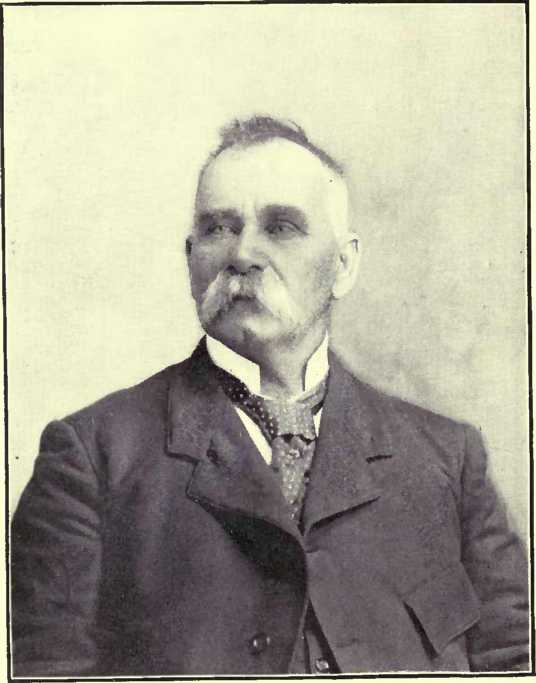

WILLIAM FLESHER

SANDERSON

THAT spirit of

adventure which is one of the characteristics of the present age, and

which has contributed so much to the development of mankind during the

last fifty years, should, when properly directed, command our highest

admiration. Without it many portions of our continent would still have

been unexplored, where are now to-day large centres of population,

actively engaged in all those pursuits which tend to develop the race

and augment their capacity for enjoyment and happiness. This feeling,

however, like other of the higher attributes of our nature, must be

properly directed to secure for the individual the greatest advantages

from its use. The man who from the mere love of change roams everywhere,

without an aim or an end in view, is not likely to add very much to his

own manhood, nor to contribute a great deal to those stores of knowledge

which enhance the pleasures and dignify the life of civilized men. On

the other hand, when we find an adventurous spirit surmounting great

difficulties in the pursuit of fortune, in the cause of science, or in

any of the many paths which rouse men to action, unselfish in its

activities, .ambitious in its various projects, observant and reflective

in its nature, we instinctively accord it our highest esteem. Many such

have come and gone in the woods of Canada, have lived and died, and

beyond the circle of a few friends were unknown. Men whose minds an

empire might have swayed, and whose aspirations placed them practically

above the vicissitudes of fortune or the influence of environment, have

found homes in the rude forest, where in calm seclusion they mused with

ever widening philosophy on the forms of nature and the great problems

of human life. To say that many of the old pioneers were men of the

character indicated would be incorrect; but we do say that many old

settlers could be found in the wilds of Blanshard whose natural ability

and acquirements were as far in advance of the average as could be found

in any society in Canada, or perhaps anywhere else.

HIS EARLY DAYS

Amongst Blanshard’s

most gifted settlers was the subject of our present sketch. His

character was unique, and in many of its aspects had no counterpart in

the township. With the bluff courtesy of the Englishman was combined the

quality of caution attributed to the Scotch; a clever reader of the

character and thoughts of other men, he is an adept at counselling his

own, is possessed of great powers of observation, and correct in all his

conclusions; from the refining force of his reflection, he has

consummate tact, an affectionate manner, and such liberality toward the

opinions of others that he has for years been one of Blanshard’s most

popular men.

William Flesher

Sanderson was born on the 23rd day of October, 1835, in the city of

Bradford, Yorkshire, England. His father, the Rev. William Sanderson,

like the greater portion of the clergy in England, was frequently moved

from one charge to another, and his son, as a matter of course, had many

changes in schoolmasters after he had reached school age.

Notwithstanding the itinerance inseparable from his father’s calling,

Mr. Sanderson was able to secure, before he reached his fifteenth year,

a fair English education. But the spirit of enterprise and adventure

which characterized his conduct during the active period of his life

manifested itself at this early age, and in spite of the tears of his

mother and kind solicitations of his father, he determined to cross the

Atlantic and seek his fortune in the wilds of Upper Canada, as Ontario

was then called. He therefore, on the 1st day of May, 1850, left his

father’s roof, where he was destined never to enter again, and sailed

from the St. Catherines docks in the city of London for Quebec. In the

bark Etheired, under Capt. McLeod, he made a successful voyage in five

weeks and four days.

ARRIVES IN QUEBEC

During the trip the

ship experienced severe weather, and the cargo shifting, the little

vessel nearly capsized in mid-ocean. Mr. Sanderson did not, however,

realize the danger of the situation. He was young, and with all the

recklessness and buoyancy of youth rather enjoyed the excitement among

the crew arising from the gravity of their situation. Mr. Sanderson

sailed from Quebec to Montreal on the John Munn. At Montreal he again

secured a passage and came on to Toronto. Leaving that city he went

northwest, and spent about eighteen months in the vicinity of Bolton

village and Port Rowan. This section did not apparently satisfy his

ambitions, and he came on farther west to the city of London. So far,

since he left the home of his parents, he, like nearly all young lads of

his age, took life with a light heart and an utter disregard for the

future. Those ties and associations which gather around men as life

passes away had not yet fastened themselves on him, and wherever he

happened to be, that spot was for the time his home.

Shortly after his

arrival in London he casually met a couple of gentlemen from Blanshard,

one a Mr. Miller, who was father of William Miller, ex-treasurer of the

township, and Mr. McCullough, who then resided on the farm now occupied

by Mr. Pearn, on the 2nd concession. From these gentlemen he received

the most glowing accounts of the township of Blanshard, and he at once

formed the resolution of coming into the locality and seeing it for

himself. On the 1st day of April, 1852, he started on foot, and the same

night found him in St. Marys, snugly quartered in the hostlery known

long after as the National Hotel. This hotel was kept at that time by

two tailors named McIntyre and Sutherland, who had laid aside the needle

and the goose, and had exchanged the business of constructing garments

for the physical comfort of their patrons, for the supply of spirituous

libations to satisfy their thirst. The climatic conditions at that time

seem to have been much as they are at present, for on that 1st day of

April an icy rain had so covered the trees as to spread distraction

everywhere and gave to the whole country a desolate and uninviting

appearance.

COMES TO WOODHAM

During the period of

his residence near Bolton village he made the acquaintance of a family

by the name of Stearns, who had in the meantime removed to Blanshard. He

accordingly went to the home of his former friend, and with him he

worked on the farm the following summer, thus receiving his first

training in the laborious occupation of chopping and clearing land. In

the fall he purchased one hundred acres of bush himself in the township

of Usborne, adjoining the village of Woodham (the site of which was then

all woods), built a log shanty, laid in a supply of provisions, which

meant pork, potatoes, and tea, and commenced chopping; his sole

companions for the long winter being a fox-hound and his own thoughts.

When we consider that this lad, who had spent his whole life among

people of politeness and refinement, and wholly unaccustomed to labor,

should have left his home and wandered away into the woods in the back

settlements of Canada, and imposed upon himself such hardships as were

inseparable from a backwoods life, his conduct appears marvellous. To

those who were born in the humbler walks of life, trained from their

youth to work and associate with men used to toil, the labor of clearing

land was not by any means so oppressive; but to him it must have been a

sad change indeed.

During the long winter

he, to relieve the tediousness of his lonely condition, frequently

indulged in hunting expeditions. On one of these occasions he found

three bears, who, no doubt instinctively to secure themselves from such

a famous disciple of old Nimrod, had betaken themselves for safety to

the branches of a tree. Being unable to dislodge the beasts, he secured

the assistance of a gentleman, a tailor by trade, who resided near him.

This person had a gun, a terrible implement of death, and considered a

fine weapon for large game, as she did not “scatter,” but carried her

shot compactly into whatever object at which she might be discharged.

The three started for the bear tree, viz., Mr. Sanderson, the tailor,

and the gun, with blood in the eyes of the two gentlemen and death in

the barrel of the piece. By some mishap, however, the lock of the

firearm had been injured, so that the hammer would not remain in

position when drawn back; and when she was used the gunner always had an

assistant to hold it back while he took aim, and at the word “fire,” the

assistant let go the hammer, when if the game did not scamper away, it

was likely to get hurt. The bears still sat in the tree in happy

unconsciousness of the measures taken for their destruction. The knight

of the needle took aim with the gun, while the duty of Mr. Sanderson, as

assistant, was to hold back the hammer. At the word “fire” he let go,

when the bears descended the tree precipitately, apparently annoyed at

such unsportsmanlike conduct. At this denouement, the tailor threw away

the gun, and with his assistant started pell-mell for the shanty,

falling over logs and brush in their retreat. Neither of the hunters

spoke or looked round until safely inside the walls of the building and

the door securely bolted, Avlien mutual congratulations were exchanged

for their happy deliverance.

During this same winter

another event transpired which exemplifies the character of Mr.

Sanderson in a marked degree. He was chopping in the woods when he heard

terrific cries from a neighbor’s fallow. Repairing to the place whence

the cries for help still proceeded, he found a Mr. Tyreman had given his

foot a fearful cut with the axe, an accident which, by the way, was

common in those early days. He assisted the man to his shanty, and

having secured a needle, sewed up the terrible gash as well as he could.

Having completed this surgical operation, and his patient resting as

easily as possible, they were startled by the blood spurting from the

wound with such force that the poor sufferer was given up for lost, and

death was expected. Mr. Sanderson ran to the house of Mr. James Nagle,

who then resided in Usborne, who promptly came and made the last will

and testament of what all expected was a dying man. The flow of blood

being somewhat abated, it was decided to send for a doctor. No medical

man lived nearer than St. Marys. There was no horse in the settlement,

and on that cold winter night Mr. Sanderson walked to St. Marys on foot

to obtain medical aid for a person who at that time was to him almost an

entire stranger. The distance was twelve miles, and he arrived next day

at two o’clock with Dr. Thayer, the only doctor in St. Marys at that

time, who properly dressed the wound, and the man ultimately recovered.

In the spring it became

necessary to have a yoke of oxen to log his fallow, and hearing that Mr.

Henry Morrill, who resided on the base line, had a yoke to dispose of,

he went there and found that he had not only an excellent yoke of

cattle, but also a prepossessing daughter, just budding into womanhood.

The oxen were purchased and taken home, yet, notwithstanding the best of

care and attention, would persist in wandering every now and then to

their old quarters. Of course they had to be brought back, which would

have been somewhat annoying had it not been that invariably these

journeys were rewarded by a little chat and an occasional smile from the

young lady of the house. Buck and Bright, the names by which all oxen

were called, continued taking their periodical trips until they had

succeeded in making the young couple intimately acquainted with each

other. Thinking, no doubt, that they had done their part in the affair,

and that the rest could be accomplished without them, they discontinued

their visits. And so it turned out, for the intimacy that had so happily

sprung up between their present proprietor and their former owner’s

daughter, ripened into courtship; and on August 1, 1853, he led to the

altar Miss Martha Helen Morrill, aged seventeen years, when the nuptial

knot was tied and they were made man and wife, their united ages being

thirty-five years.

Some time prior to

their marriage he purchased the west half of lot No. 7, on the 6th

concession, Blanshard, where he built a home, into which he took his

young wife, and never again resided on his property in Usborne. Of this

union there is no issue. Mrs. Sanderson, young and inexperienced as she

was at the time of her marriage, has proved herself an excellent

helpmate, and nobly assisted him in all his efforts to carry out

successfully his schemes either for his material or political

advancement. On this farm he continued to labor and make improvements,

until he finally sold it to Mr. Amos Marriott, who owned the adjoining

property and purchased the place on which he at present resides.

THE OLD LOG SCHOOL-HOUSE

About the year 1855 or

1856 he was honored by the first mark of public confidence he ever

received from the people, by being elected to the office of school

trustee, in which capacity he served for six years. At that time the old

log school-house, which had been erected when the country was nearly a

wilderness, was found, after the settlement had extended to the west, to

be entirely inconvenient and far away from the centre of the section as

at that time constituted. The old building stood on the identical site

on which Cooper’s church now stands. An agitation sprang up in the west

end to remove or erect a new building in the centre of the section. Mr.

Sanderson espoused the cause of the western ratepayers, and succeeded in

carrying a resolution authorizing the trustees to erect a new building

during the year, farther to the west. However, before anything had been

done, the council undertook to remodel the school sections in the

township, so that the buildings would have to be erected mid-way between

the concessions on the sideroads. This move of the council was violently

opposed by the ratepayers generally, and particularly by those on the

upper end of the base line. Public meetings were called to discuss the

matter, when arguments in powerful and emphatic language were hurled

from one side to the other by the opposing parties. Mr. Sanderson at one

of these meetings was appointed to interview the council, and try to

arrive at a solution of the difficult question. This was the first time

he had ever been within the doors of the council chamber. The Hansard

not having been introduced in Canada at that time, no record has been

preserved of the speeches on that occasion. He pointed out to the board,

however, that the swamp between the base-line and the site where the

buildings would be erected would have to be navigated by a boat, as the

water in the fall was usually three or four feet deep. In the winter,

when the boat could not be used, there would be no road at all. He also

pointed out to the assembled wisdom that no ratepayer would be guilty of

such barbarous conduct to his children as to send them into the woods to

a school where in the summer they would have the last drop of blood

sucked out by mosquitoes and the last morsel of flesh picked off their

little bones by flies. The council sat with that respectful gravity for

which the members of the Blanshard board have always been noted when

addressed by the people, but admitted the matter had gone too far to

stop, and the people would have to make the best of it. This was an easy

way to dispose of the question, surely. The people on the 8th concession

took action immediately by organizing and letting the contract of

building a school-house, the site selected being on the dividing line

between the lots owned by Captain John Campbell and Fletcher D. Switzer,

on the upper side-road. The mechanics were soon at work, and the sound

of the axe and the hammer, as it came echoing through the woods to the

base-line, was doubtless provoking, but was borne in sullen silence by

the opposing party. At last on a calm, still night, when the moon’s pale

light shone softly o’er hill and dale, and the building was nearing

completion, there came a mighty crashing sound like the roar of an

avalanche, that roused the whole neighborhood from their slumbers,

particularly those on the head of the base-line. Next morning people met

each other with faces white with fear, asking each other if they had

heard the terrible noise. Apparently they all had, but none could assign

a cause. As the day advanced, however, it became known that the new

school-house had been literally torn to pieces and smashed into kindling

wood. The havoc wrought on that calm, still night was looked upon by the

base-line people as a special interposition of Providence, and that some

superhuman power had been brought into play to assist them in their

extremity. The people on the 8th concession were, and always remained,

skeptical on this point, arising no doubt from their materialistic

tendencies. Be the cause what it may, it stopped forever the insane idea

of building our school-houses on the sideroads. In the following year

the Board of Trustees on the base-line, composed of Mr. Sanderson, Mr.

Cathcart, and Mr. Gooding, erected in the centre of the section on the

base-line the first brick school-house ever erected in the township of

Blanshard.

Another incident which

occurred about this time will bear repeating. The old settlers (happily

for society) brought with them into the woods a heart-yearning desire

for those sacred ordinances and spiritual consolations on the

perpetuation of which must ever rest, as on a sure foundation, the

structure of civilized life. To their humble homes, and to the rude log

buildings here and there erected in various parts of the township, good

and self-denying men picked their way through forests and dispensed the

bread of life to the little congregations of the early settlers.

At a very early day an

Orange hall had been erected on the corner of Mr. David Brethour’s farm,

on the base-line, and in which religious services were held. If the

accommodation was poor it was the best that could be obtained. Planks

laid across blocks of wood were used for seats, not only for the

congregation, but for the minister as well. On this particular night the

little place was crowded; and when the subject of our sketch entered, he

was shown to a seat on the platform where a plank had been placed for

the minister, and on the centre of which the good man was sitting,

preparatory to beginning the service. On the farther end of the plank he

had placed his hat, a fairly good plug. Mr. Sanderson reverently took

his seat on the other end. On the minister rising to begin the service,

down went Mr. Sanderson’s end and up went the other, hoisting the plug

hat up to the ceiling with great force, and finally landing it back

among the congregation. Our friend still stuck to the seat, when the

farther end, on which had stood the hat, swung round over the heads of

part of the worshippers, who in looking up saw, not the spirit

descending on them like a dove, but the swaying end of a two-inch plank.

At length order was restored, he was relieved from his position, and the

service proceded.

ARMED WITH A PASSPORT

In the spring of 1863,

with the adventurous spirit that characterized him, we find that he had

rented his property in Blanshard, and was on his way to the Pacific

coast, by the old pioneer route of Panama. He was sailing through Cuban

waters at the time when that noted privateer, the Alabama, captured the

American steamer Ariel. After crossing the Isthmus, smallpox broke out

among the passengers, when the ship had to run into Porto Rico and put

the sick ashore. By this means they were allowed to pass the Golden Gate

into San Francisco with a clean bill of health.

It may seem strange to

our readers that in the year 1864, in the highly civilized country of

the United States of America, a traveller from a foreign country could

not pass through their territory without a passport to insure him from

detention and secure his safety. We are apt to commiserate the people on

the continent of Europe who are constantly tormented with passports in

moving from place to place, but we did not think that it would ever be

necessary on this side of the Atlantic to take such precautions. We

find, however, that on March 28th, 1864, it is certified “that the

bearer, William Flesher Sanderson, whose signature I have caused to be

placed in the margin hereof, is a British subject on his way to

California. Signed, Josias Bray.” Then follows a description of Mr.

Sanderson as he appeared in the flesh thirty-five years ago: “Age,

twenty-eight; height, five feet six inches; weight, 160 pounds; color of

hair, light brown; color of eyes, light grey; complexion, fair.”

Attached to this document we find that John D. Irwin, United States

Consul at Hamilton, Upper Canada, further attests that he was present

and saw the annexed document signed by Josias Bray and Mr. Sanderson ;

and faith and evidence should be given to the said paper, as Mr. Irwin

further certifies that the signature of Mr. Bray was genuine. In witness

whereof Mr. Irwin sets his hand and the seal of the consular agency at

Hamilton, Upper Canada, on the 28th March, 1864, and of the independence

of the United States. Armed with these papers, Mr. Sanderson accordingly

proceeded on his way to the Pacific Coast.

IN THE MINING CAMP

At this time the mining

camps of Washoe were the centre of attraction, and thither our subject

bent his steps, passing through California, across the Sierra Nevada

Mountains, by way of the Hennis Pass, into the adjoining territory of

Nevada. Here he finally settled at Virginia City, in the world-famed

Comstock lode, having walked every foot of the way in company with four

others from the City of Sacramento, a distance of 217 miles. Each man

carried his outfit and some provisions. This was made into a bundle

which he carried on his back, held by a strap which passed across his

breast. One evening when they reached the summit of the Hennis Pass, and

in the region of everlasting snow, they were so fatigued they could

proceed no farther. To have lain down on their blankets would have been

certain death from exposure to the intense cold in such high altitudes.

They fortunately found a small cabin built of boards, where they each

paid a dollar for the privilege of spreading their blankets on the

floor, where they might rest for the night. In the morning they set out

again on their dreary way, and pushed on toward the Eldorado where all

expected to find gold.

The city of Virginia at

this time was composed partly of tents and partly of buildings, and was

the liveliest camp on the face of the earth. There was no difference

then between night and day, Sunday or week day, so far as work and

amusements were concerned. Some danced all night, some gambled all

night, and some worked all night, changing places with each other for a

rest. There were also churches there and a few good people doing their

utmost trying to stem the torrent of vice and bloodshed. But

notwithstanding their best efforts, many, very many indeed, were laid to

rest in the graveyard across the Gould and Currie ravine, slain by a

brother’s hand. Law at this time was set at defiance. The courts were

helpless ; every man went armed, and not until the vigilance committee

went to work in good earnest, hanging men up by the neck, ticketed with

the committee’s initials 602, was there any reformation.

Not long after the

organization of this committee, an opportunity offered itself for a

display of their ghastly operations. A young man by the name of Perkins

had received from one of the frequenters of the saloons what he supposed

was an insult, and, in the true spirit of the place, at once drew his

revolver and shot his opponent on the spot. This young person was a

piano player in what was known as Scott’s dance house, one of the hells

in Virginia City. This man the committee determined should be their

first victim. On the night following the committal of the crime he had

retired to his room and was preparing to undress, and had removed one of

his shoes. The committee entered his chamber, seized the young fellow,

and partly undressed as he was, bore him off to the place of execution

decided upon, where he should expiate with his life the crime he had so

recently committed. He begged piteously for his life, or for such time

as to write to his mother, who was far away in the east, perhaps at that

very moment thinking of her son. But prayers and supplications were lost

on the unrelenting hearts of his murderers, and with the shoe removed

from one of his feet, and the other still on, he was led to the place

selected for his execution. This was at a mine contiguous to the city.

At the entrance, where the drift penetrated the side of the mountain, a

frame-work was erected to prevent the earth falling on the roadway

beneath it. Under the frame-work a wagon loaded with ore was drawn, and

the culprit placed thereon. A rope was fastened to the frame over head

in the mine and round the man’s neck, when the wagon was withdrawn and

the poor fellow launched into eternity and ticketed as the first

offering of the number 602.

That such a state of

affairs should exist within the territories of what we consider as one

of the most highly civilized nations in the world, indicates in a marked

degree the carelessness and neglect by the central authority of the

highest functions of government—the protection of the lives and property

of its citizens. The triumvirs of the French Revolution were not more

potent for evil than this association which had adopted for its trade

mark the number 602. It made its own laws, reached out its irresistible

arm for the victim, was its own judge and jury, condemned the culprit,

and led him to execution. The state of society must have been deplorable

that sought its safety in the power of such a tribunal. Indeed, so

callous had the people become to the waste of human life that the two

daily papers published in Virginia City, when no murder had been

committed during the night previous, had in their leading column in the

morning, printed in large letters, “No man for breakfast this morning.”

We would not have dwelt

on this subject to so great a length but as a warning to any of our

young and adventurous Canadians who may read this sketch, to consider

well before casting iu their lot in a country where such a state of

things could exist. Let them contrast the position of the Yukon with

that of Virginia City. Many of these old prospectors who had played

their part in the scenes described attempted to establish the same state

of thing in the Yukon ; but there they found British justice meted out

by that arm which is ever ready and always able to maintain order and

protect the lives and property of her humblest citizen, not only within

her own borders, but in every corner of the earth.

On a beautiful quiet

summer evening, the subject of our sketch, having completed the labors

of the day, had retired to his cabin for the night. Sitting alone by the

fire and ruminating no doubt on his past adventurous life, and building

air castles in the future, he was aroused from his reverie by a knocking

at the cabin door. He made hasty preparations to receive his visitor, as

was the custom in that country, by examining his arms to see if they

were in condition to meet the worst. Whether it passed through his mind

that he might be wanted for a sign-board where the No. 602 might be

tacked on or not we are unable to say. He cautiously unbolted the cabin

door, and there stood before him a tall, lean, bony man, with a slouch

hat, who at once extended his hand, grasped Mr. Sanderson’s, and shook

it vigorously. This man was Mr. John Hannah, from Kirkton. The surprise

of both men, and the congratulations that passed between, may be

imagined. After a pleasant chat about Blanshard and old times, Mr.

Sanderson, being a true Englishman, set about making preparations for a

great feast next day, it being the Sabbath. His larder not being richly

provided, he, in company with his guest repaired to the city, where he

intended to lay in a supply of mutton and beans for dinner. As they were

walking along they stepped into a gambling saloon, where Mr. Hannah

could see for himself the style of living in Virginia City. As they

stood near one of the tables, a tall, respectable looking gentleman came

forward, and placing his hand on the table, happened to lean on one of

the men engaged in play. This man pushed the gentleman somewhat rudely

away, when without a word being said on either side, he drew his pistol,

fired, and shot the player dead. Mr. Hannah, who had lived his whole

life among the quiet shades of Fish Creek, was horrified, and left the

saloon in terror.

Mr. Sanderson having

secured his mutton and beans, they returned to the cabin, where, after

conversing on old times till the night was far advanced, they retired to

their repose. In the morning Mr. S. was astir bright and early,

attending to his duties, and making preparations for a great dinner. The

mutton and beans were placed in the oven and a blazing fire built in the

fire-place. Both gentlemen were enjoying themselves rehearsing the many

scenes incident to backwoods life in Blanshard, and forgetting the

roast. At last Mr. Hannah drew attention to a great smoke proceeding

from the the oven where the meat and beans were cooking. On opening the

door it was found that the food had taken fire from the excessive heat.

The host rushed to the stove, grasped the savory dish, drew it out and

in his haste spilled the whole contents on the cabin floor. This was a

sad catastrophe, but he was equal to the occasion. He seized a ladle,

scooped up the savory particles, and served them up in his best style.

Of course he scooped up more than mutton and beans, but the pieces of

clay that ground in their teeth as they enjoyed their repast seemed only

to give zest to what was declared by both gentlemen as an excellent

dinner. Some time after these events another gentleman from Kirkton

appeared on the scene in the person of Mr. William Hannah, brother of J.

Hannah, who was father to John and William Hannah, at present residing

on the old place between Woodham and Kirkton. This unfortunate and

kind-hearted man, shortly after coming to Gold Hill, lost his life in

one of the drifts. Mr. Sanderson, with the true Canadian spirit,

obtained his body, prepared it decently for burial, and reverently laid

it in its last resting-place.

IN HASTINGS COUNTY

In 1866 we next find

the subject of our sketch, who, in the meantime had been joined by his

wife, making his way out of Mexico, as war had broken out in that

country. On reaching the city of Acapulco, on the coast, they were

kindly proffered the protection of the Post Captain of the French fleet,

which had just captured the Fort in the interest of the ill-fated

Maximilian, and which offer they cheerfully accepted. Setting sail

again, it was the 9th of August before they reached the Isthmus, in the

midst of the rainy season. Here Mr. Sanderson was seized with the Panama

fever, which kept him very low during the rest of the voyage and for

some time after he reached New York. He finally, however, reached his

home in Blanshard in safety. With restored health was also restored that

spirit ,of adventure which in him was ever restless. He was now in the

prime of life, full of that energy which urges men on to seek fame and

fortune at any cost. In the county of Hastings the gold fever had broken

out. Some prospectors had discovered that the precious metal existed

there in paying quantities ; and thither he went, continuing over twelve

months in search of gold, but without any degree of success. During his

residence in Hastings county there lived near him a poor Frenchman, a

laborer, one of whose children died during a severe snowstorm in that

inhospitable country where the gold mines were located. The little child

was about twelve months old, and the parents in indigent circumstances.

A coffin was made out of such material as could be procured on

principles of economy. The Frenchman, being a Roman Catholic, could not

bear the thought of having his little one laid in the earth without a

clergyman being present. No clergyman of his own Church being within

reach, Mr. Sanderson procured the services of a Protestant minister,

which appeared to satisfy in some degree his desire that the rites of

Christian burial should be performed over the body of the little one.

Mr. Sanderson had the only horse and cutter in the locality, and he took

the little coffin with him to the graveyard. The few people that were

present had reached the place of interment by a shorter route than he

was able with his horse to take, owing to the drifts. He accordingly

tied his horse to the fence at some distance from the grave, and taking

the coffin in his arms, walked over the snow to the fence, which he

proceeded to climb. He had no sooner mounted it than it gave way, and

the coffin falling, broke open, and the little corpse rolled out in the

snow. At this state of things he was horrified, but he took up the

little body, wiped the snow from its pale face, and adjusting the

cerements that covered it, placed it again in the receptacle and moved

on to the grave. Here they nailed the lid as well as they could and

consigned the little inanimate form to its kindred earth.

HIS MUNICIPAL CAREER

Not being successful in

the county of Hastings, he returned to Blanshard for a short time, when

he again left for the Pacific coast, certain interests he had in some of

the mines in that country demanding his attention. He did not remain

long, however, and having arranged his affairs, came back to Canada, and

in 1874 returned to his native England to visit his widowed mother for

the last time. Here he stayed three months, when he again returned to

Blanshard, where he has resided continuously ever since. He did not

remain long idle in his home. The people at the nomination of 1878

placed his name on the nomination paper for that year as councillor in

the township. He was elected and sat for one year in that capacity. In

1879 he was elected deputy reeve. In 1880 he was again elected deputy

reeve, and again in 1881. In 1882 he was elected reeve, and the same

year he was elected warden of the county. In 1883 he was defeated in his

election for the reeveship, and was again elected 1884, since which time

he has never been an aspirant for township honors. He has served the

municipality ever since, a period of the time as auditor, and has been a

member of the Board of Health since its inception. In 1885 or 1886 he

was elected on the Board of Directors of the Blanshard Mutual Fire

Insurance Company, and the same year was made president of that

institution, which position he has held ever since. He is a director and

salesman of the Blanshard Cheese Company, on the base-line, and for his

service in this connection was presented by the company a few years ago

with a handsome acknowledgment of his services. At the introduction of

the New Municipal Act, forming the county into districts, in 1897, he

was nominated, with Mr. Monteith, of Downie, the member elect for South

Perth, as the first commissioners for District No. 4. Both gentlemen

were elected, and at the nomination for 1899 and 1900 the same gentlemen

were elected by acclamation. About five or six years ago he received

from Her Majesty a commission as J. P. in and for the county of Perth.

In all these various positions of trust which he has held, we believe he

has discharged his duty honestly and well, and has the satisfaction of

knowing that if he has erred it has been through lack of judgment and

not from intention.

HIS SOCIAL QUALITIES

With the exception of

Mr. Cathcart, he has been, perhaps, as popular as any of Blanshard’s

public men. He had the faculty in an eminent degree of gaining the

confidence of men, and what was of equal importance to his success, he

had the tact to retain it. This arose from his native kindness and an

equanimity of character and temper which could hardly be excelled. It

made little difference what may have been said by his opponents, he

still came forward with the same smile and the same shake of the hand.

In his contests he was always cool, calm, and collected, and his whole

nature seemed as placid and quiet as a summer sea. We never saw him,

even when hardly pressed, ever indicate by word or action the slightest

temper. He is polite and affable in his communications with the public,

and in private his conduct is of that refined character that we almost

invariably find in the sons of the manse. As a public speaker he is far

above the average, although he lacks that fire which seems to rouse

men’s dormant energies into life and stimulate them to action. He is

always pleasing, his language exceedingly good, his sentences well

rounded, is a good reasoner. and has the faculty of saying nice things

in a nice way and at the right time. In listening to his speeches you

feel pleased with him and pleased with yourself, but you miss the

tingling sensation aroused in your bosom by that overpowering energy and

heat which some speakers have the power of throwing into their

addresses. He is a jovial companion at the social board, can tell a good

story and sing a good song, and in every way is both able and willing to

contribute his share to the enjoyment of the company. As a farmer we

cannot rate him very high. Although everything around his farm is kept

tidy and neat, still we do not think that running a farm is his forte.

He was far too adventurous to remain on a farm, and if he has made it

his home all his life, still we think that he did it rather from force

of circumstances than from a lieart-felt love for the occupation. He is

below the average height, and in his youth was slightly built, but we

might now adapt Mr. Mulock’s postage-stamp motto to his upper garments,

“We hold a vaster empire than has been.”

He is a good

entertainer, with the happy faculty of putting his guests at their ease,

and he caters to their comfort with the most generous hospitality. In

politics he is independent, claiming alliance with neither of the two

parties. He is not offensive in forcing his opinions on others, but when

discussions arise, as they sometimes do, he can enforce his ideas with

dignity and firmness. In religion he is liberal, believing that such

things should be left between God and men’s own consciences, and that

they should worship at whatever altar they may think fit.

But we must now close

this imperfect sketch of the life of a very remarkable and popular man. |