|

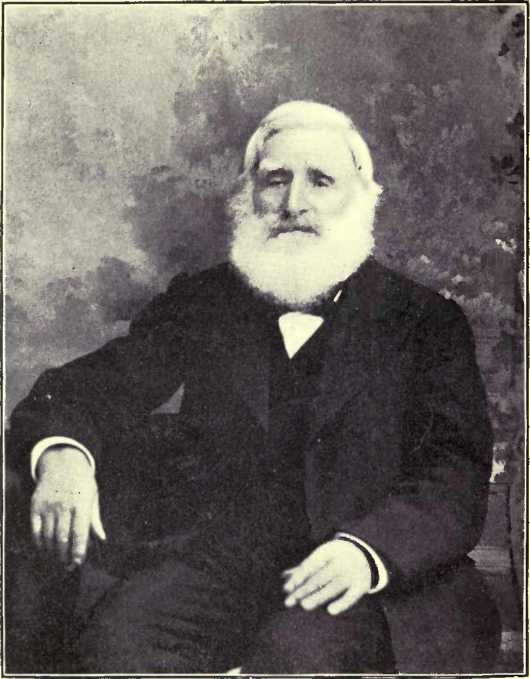

REUBEN SWITZER.

BETWEEN fifty and sixty

years ago, the subject of our present sketch joined that great stream of

emigration from old Ireland seeking fortune in America, and which stream

still continues to flow, although perhaps in somewhat diminished volume.

All of that great tide of humanity shared this one great and

predominating feeling, that “they left dear old Ireland because they

were poor.” In their native land they saw no prospect of bettering their

condition. Their lives so far had been one constant struggle, and

notwithstanding the most rigid economy and thriftiness, they had still

remained on the ragged edge of poverty. In all the cabins surrounding

their own the same order of things obtained, and the most sanguine

hearts of a most sanguine and light-hearted people could see no opening

in the surrounding circumstances that would lead them to believe that

better days were close at hand. To a traveller passing through the rural

districts of Ireland the evidences of this exodus are present

everywhere. Here and there amongst the low hills and green valleys stand

in staring vacuity the old homes of the departed emigrants. You visit

one of the many of these places, and everything about it is ruin and

decay. There is nothing to indicate that within these old walls scenes

of human joy, sorrow, or suffering had ever been enacted. The clay floor

is a mass of rubbish, composed of the thatched roof that offered shelter

in better days. The hinges on the door are rusted away, and the openings

of the windows seem vacuous as the eyeless sockets of an old skull. On

the spot where the turf fire blazed and cracked nettles and weeds grow

up in luxuriance. Around the door, where perhaps some of Blanshard’s old

settlers played in infancy, the grass grows green. The spring near the

old cabin flows on bright as it did before, and with the same song, but

no one is there now to taste of its waters. The little farm of an acre

or two has passed into other hands, and the last inhabitant of the old

house has been so long gone that, excepting for the rude stone in the

little churchyard that marks the last resting-place of some one still

dear to the emigrant, his very name would be forgotten. To a traveller

of a reflective mind a visit to these old places has a most impressive

effect. There must have been some extraordinary circumstances to produce

such extraordinary results. The ties that bind most people to the spot

of their nativity are not easily broken, and the conditions that led to

so many ruined and empty homes in that unfortunate country must have

been unbearable indeed.

BON IN “OULD OIRELAND”

On the banks of the

river Shannon, in the southeastern part of Ireland, stands the old

historic city of Limerick, near which, in the village of Adare, was

born, on the 1st day of September, 1813 (or nearly eighty-six years

ago), Mr. Reuben Switzer, the subject of our present sketch. Like nearly

all of the old settlers of Blanshard, he was the son of a small farmer

who tilled a few acres for the support of his wife and family. He was

the eldest of thirteen children, seven of whom came to Canada and

settled with their father in the new township of Blanshard, in the year

1843, the subject of our sketch not coming to this country till 1846, or

three years later. Of the six sons who came to Canada, four are still

living—William, on the 3rd concession; Reuben, on the 2nd concession ;

Henry, on the Mitchell Road ; Adam, on the 14tli concession. Richard,

who lived on the Mitchell Road, died many years ago, and Cornelius, who

lived on the 2nd concession, is is also dead. Every one of these men

were energetic, enterprising, and thrifty, all having acquired good

farms and an honorable name among the citizens of the township.

The subject of our

sketch, being the eldest, was early inured to toil, assisting his father

on the little farm, and thereby contributing something to the support of

the younger members of the family. He, however, when his other duties

would permit, attended a school in the neighborhood, until he reached

his fourteenth year. This seminary of learning was conducted on the same

lines as nearly all similar institutions in Ireland seventy years ago,

with this exception, perhaps, that the teacher in this case was an

extreme disciplinarian. His name was Armstrong, and Mr. Switzer has

still a lively recollection of his efforts to maintain order at the seat

of learning over which he presided. The building in which Mr. Armstrong

trained the young idea how to shoot was in part of an old ruined castle.

Apparently the genius of the ancient barons who, if they did not do as

they pleased among the armies of heaven, certainly did so among the

inhabitants of the earth, had fallen on the shoulders of the pedagogue,

who was untiring in asserting his prerogative among his scholars. In his

theological researches he had taken to heart that piece of philosophy

that “he that spareth the rod spoileth the child.” In his dealings with

the school he kept this constantly in mind, so much so that the position

held at the court of James I. in his youth by Sir Mungo Malagrowether

might be considered a sinecure. The methods adopted by the profession of

the present day to maintain order among the attending youth would have

merited the utmost contempt from this old champion of the taws. He did

not believe in teaching by induction, by pronunciation, or oral

communication, but had unbounded confidence in communicating his ideas

by inoculation with a good stout stick. As a matter of course, the more

assiduous he was to instil into the young people the great educational

truths he conceived were for their best interests in this way, the more

careless and disinclined they were to receive them. Under these

circumstances not much progress was made. As we have already observed,

he was most punctilious in his observance of the rules laid down in the

school. To attain the highest point of excellence in this way, a board

was hung up at the door, on the one side of which was printed the word

“out” and on the reverse side the word “in.” Mr. Armstrong, no doubt

desirous of devoting as much time as possible to his scholars, had no

recess between the hours of nine in the morning and four in the

afternoon. As might be expected, many of the scholars would have

occasion to retire during this long period of confinement. To prevent

any interference with the onerous duties of the master, when a boy

desired a short recess he turned the board with the word “out” toward

the teacher, and when he returned he reversed it, showing the word “in.”

On one occasion a young scion of the honorable house of Moriarty, one of

the scholars, inadvertently entered the sacred hall without turning the

board, and took his seat, the word “out” still glaring on the unturned

sign. Mr. Armstrong, seeing this state of affairs, considered it an

unpardonable breach of discipline, and proceeded to point out to the

young gentleman who had sat down the gross infringement of the rules of

which he had been guilty. “Mistlier Moriarty, come up here, sor,” said

Mr. Armstrong. The representative of the Moriarty family accordingly

advanced to the front. “Do you see the board, sor?” Mr. Moriarty

signified his assent that he saw the board. “Do you see the word ‘ out

sor?” The young gentleman gave his assent, and mildly hinted that he had

omitted to turn the board as he came in. Mr. Armstrong assumed a look of

great dignity, and said, “ Mr. Moriarty, so long as that board shows the

word ‘out’ you’re out, and not till it shows the word ‘in’ are you in.

Be careful, sor, and not break the rules of the school.”

STARTS FOR AMERICA

Having bid farewell to

Mr. Armstrong and school days, he stayed with his father on the farm and

did what work he could get in the neighborhood, until he reached his

20th year. In 1833 he married Miss Sparling, the daughter of a

neighboring farmer, and began life for himself, having in the meantime

obtained the position of steward to a gentleman in the county Clare.

In this position he

stayed nine months, when a similar place with more remuneration was

offered to him in the county of Kerry, about six miles from Tralee. Here

he stayed for three years, overseer on an embankment which was being

constructed to keep out the sea. Having completed this work he again

moved back to Limerick, to a place called Castletown Waller. Here Mrs.

Switzer obtained the position of laundress to the Rev. Mr. Waller, while

he worked on the estate, his wages being at the rate of one shilling per

day, the highest wage he ever received in Ireland. He remained here for

seven years, when the savings of himself and wife during that time

amounted to what he considered a sufficient sum to warrant him

undertaking the journey to Canada. Previous to this, however, his father

and brothers had, in 1843, left Ireland for this country, and had

reached the Mitchell Road, where they located the farm on which Henry

Switzer now resides. In April, therefore, in 1846, he resolved to follow

the rest of the family, and the 18th day of that month saw him, his

wife, and five children on board a ship at Limerick, under Captain Hugol,

for Quebec. After seven weeks tossing on the Atlantic they at last

reached their destination. At Quebec he was detained seven days in

quarantine, when, through the kindness of the captain, he obtained a

pass to Brantford, which was most opportune, as his supply of cash was

very small indeed. Having reached the town of Brantford, he obtained a

lodging for his wife and family, when he left for Blanshard on foot, and

made the distance, sixty miles, in one day.

We must notice in

passing, however, a circumstance that occurred on the voyage, which, in

those days of long periods in making a trip across the Atlantic,

sometimes happened, but which in these days of fast steamers rarely ever

occur. This was the death of a passenger a woman, who was buried at sea.

The scene on board the little vessel in mid-ocean, when the body was

committed to the deep, was most impressive and one which Mr. Switzer can

never forget. Those who have crossed the ocean know that in a very short

time the passengers on board a vessel seem to each other as if they all

belong to one family, and soon acquire a kindly interest in one another.

Any occurrence affecting anyone is quickly noticed, and rouses the

feelings to a greater degree than the same occurrence would do on land.

On the morning preceding the burial, notices were posted here and there

on the ship, setting forth that the body would be committed to the sea

at a certain hour. It was a beautiful day, and a cloudless sky was

mirrored in the great ocean that lay beneath it like a sheet of glass.

On the deck the passengers moved around as if afraid to disturb the

quiet repose that seemed everywhere. During the previous night a

passenger had come on board unbidden, of pale, ashy aspect, and of cold

and unrelenting hand. He had stricken and claimed the victim now to be

buried in the still waters. At length the ship’s bell began to toll

slowly in the solemn tones of a funeral knell. At one of the hatchways

on the upper deck two stout sailors were seen to emerge, followed by two

more with heads uncovered and moving with that measured and solemn tread

that seemed to keep time to the tolling of the death bell. They bore

between them the dead body, which had been tied up in a piece of

sail-cloth, with a great weight fastened to the feet. The mournful

cortege moved round the ship till it came to a part where a board had

been laid to receive the remains. On this they were placed, when the

captain took his place and read the beautiful service of the Church of

England. As he reached the words “ O death, where is thy sting? O grave,

where is thy victory % With the full hope of a glorious resurrection, we

commit this body to the deep,” one end of the board was raised, and all

that was mortal of the poor emigrant shot down into the dark sea with a

weirdlike splash that seemed to strike every person on board with

horror. All looked eagerly over the side of the ship, but nothing was to

be seen but a slight ripple on the face of the deep water. Orders were

now given to the men to man the yards, the boatswain piped for wind,

which slowly arose, filling the sails, and the good ship bore away to

the distant west, dashing the water from her prow with her load of human

freight.

SETTLES IN BLANSHARD

Having arrived in

Blanshard, in 1846, his first efforts were directed to obtain work. This

he found with Mr. Creighton on the base-line. With Mr. Creighton he

stayed for one month, and received for his services twenty-eight bushels

of wheat, which Mr. Cathcart took to St. Marys with the oxen and had

made into Hour. Preparatory to bringing his family into the township, he

built a shanty on the Mitchell Road, where they resided the ensuing

winter. Continuing to labor on the farm for a couple of years, he

learned the best methods of clearing land, which was of great importance

to a new settler in those days. In 1848 he located on lot 8, in the 3rd

concession, which farm lie still owns. In this affair he was unfortunate

from a financial point of view. The Canada Company’s lands in Blanshard

were being sold to actual settlers at $3.00 per acre, and ten years to

pay the principal, with interest at the rate of 6 per cent, per annum.

Through some mistake the papers obtained from the Company’s agent were

informal, and at the end of the ten years, when Mr. Switzer applied for

his deed, it was found that he really had no fclaim. In the meantime the

lands in the township had become valuable from the improvements made by

the early settlers, and the Company, availing themselves of these

circumstances, raised the price of their lands to $13, $16, and $20 per

acre. Mr. Switzer was thus compelled to take his land at the latter

price or lose all his improvements. For a person in his financial

condition, this was a terrible blow. To have recourse to law proceedings

with the Canada Company would have been madness, and he quietly assumed

the responsibility, and by the most determined efforts succeeded in

liquidating the debt in a few years. To enable him to surmount such

great difficulties, he contracted for clearing land for some of the

farmers whose circumstances permitted an expenditure of money for that

important object. He in the short period of two years cleared for Mr.

Shier, of Wood-ham, land to the extent of fifty acres. To those old

settlers who understand the clearing of land this will appear as an

extraordinary amount of labor to accomplish in such a short time.

The chopping and

clearing of land, laborious as it is under any conditions, is to a

novice almost a hopeless task. He was considered a good axeman fifty

years ago, if he was able in the course of seven or eight days to chop

an acre of land. Much depended, too, on the falling of the timber for

the ease with which it was afterwards disposed of. A bushman who

understood the throwing of the large trees side by side, and perhaps

laying another equally large across so them that it would balance and

could easily be swung around and laid lengthwise with the other two,

thus forming what was called a roll pile, had a great advantage when the

timber was logged and burnt. This chopping was done in the winter, and

forty years ago in all directions through the leafless woods, was heard

the crash of falling trees and the hollow boom as some great old monarch

with far extended arms struck the ground. In the evening, when the

shades of night began to settle down on the dark forest, and from the

other side of the little clearing the backwoodsman could see the twinkle

of the tallow candle from the only window in his shanty, within whose

humble walls waited and watched his wife and her little ones, with what

determined and renewed energy he buried the axe at every stroke, until

the great tree cracked and tore and fell thundering to the earth, when

the voices from the vast forest echoed back in reverberating tones the

sound of its fall. This was called the evening gun. In the spring,

usually about the end of May or the first of June, the brush was burnt

from the fallow, and if a good burn had been made the scene was about as

uninviting a one as it was possible to see.

OLD-TIME LOGGING BEES

The brush having

burned, the next stage in clearing land was the logging. A gang of

loggers was usually composed of four rollers, a yoke of oxen, and a

teamster. The duties of the loggers was to pile up the logs into great

heaps preparatory to burning them. An acre was supposed to be a good

day’s work. Sometimes it was decided to make a “logging bee,” when the

fallow would be staked out in lots of one acre to each gang of men. The

logging bees were considered great occasions in those olden days. In the

early morning in summer men gathered from all directions through the

woods, each one with a handspike, the only implement he would use during

the day. The handspikes were usually made of maple—that timber being

exceedingly stiff—slightly flattened on the top near the point, and

rounded at the other end for the hands of the logger. All the men and

the oxen were arranged at one end of the field, and stood chatting,

laughing, and telling stories till they commenced the labors of the day.

The attire of the loggers was simplicity itself. A straw hat, a shirt,

usually home-made, and a pair of light pantaloons completed the outfit.

The shirt was always open at the bosom, and the sleeves rolled up to the

armpits, a belt around the waist (no braces); a handspike in his hands,

and the man was ready for business. The grog boss was always present,

dispensing the contents of his jug with frequency and liberality. A

couple of choppers were also appointed, whose duties were to be on the

field and cut any logs that might have been omitted in the winter. At

last the word is given, and every man takes his post determined to

complete his allotment before anyone else has finished his. The scene

where all was comparative quietness becomes at once animated and

exciting. The movements and the shouting of the men, the voice of the

teamster calling to the oxen, here and there clouds of ashes arising as

the logs are drawn over them. In a few minutes the men are as black as

the smut of the burnt timber can make them. The grog boss is hurrying

here and there over the field, with a pail of water in one hand and a

jug of whiskey in the other, supplying the wants of the thirsty men.

Each one helps himself to a cup of the one and a “corker” of the other,

and with the perspiration streaming from every pore, enters with

invigorated force into the race. So the work goes on until each one has

finished his “through,” when all wend their way to the shanty to fortify

the inner man with the goods spread in endless profusion on the tables.

The timber being at

last all burnt, the field was fenced and the next season sown in wheat.

No cultivation was required, and indeed none could be given, the land

being one solid mass of roots and stumps. The grain being sown, the

settler took his harrow—an implement made with the axe from the fork of

a tree, in the shape of the letter “A,” in which nine teeth, each about

one and a half inches square, were driven, four on each side, and one at

the point—and with that very imperfect article the whole of the

settler’s crop was harrowed in. The man was full of hope, indeed, who

could walk all day at the heads of a pair of oxen, with one of the

harrows we have described trailing at the end of the chain fastened to

the yoke laid on the neck of the poor cattle. But such was the only way

that the work could be done. The reward in many instances—nay, in every

instance where ordinary care and foresight was taken—has been sure. A

vast number of these old gentlemen who drive into the country towns in

Canada with costly carriages and trappings, began their career exactly

as I have described, and are now passing their declining years in

comfort and ease; and all this has been accomplished by thousands of men

still hale and hearty. No further evidence is necessary to show that

Canada, as a field for the sober, industrious, and energetic man, has

rewards to give which can be found in no other country in the world. The

high moral tone of her people, the vigorous administration of the law,

affording the fullest protection to life and property, the liberality of

her institutions, the fertility of her soil, offer everything to the

emigrant in quest of a home.

AS LICENSE INSPECTOR

Mr. Switzer, therefore,

as time passed away, became possessed of a fair portion of this world’s

goods. As a public-spirited citizen, too, he has taken an active part in

public life. When the township of Blanshard was first organized, he

offered himself as a candidate for the office of councillor, and was

elected on two occasions as a member of that body. On his retirement

from the municipal board he was appointed License Inspector for the

municipality. We of course do not know what the duties were exactly, but

the emolument certainly was not such as to lead a man quickly to wealth

and independence, being only $10.00 per annum. He had, in making his

various peregrinations over the municipality, performing the duties of

his office, every opportunity of ascertaining the quality of the various

viands disposed of at the different hostel-ries in the township.

Blanshard, at the period of which we write, must have been a place where

all the thirsty settlers in Canada had located, as it contained no less

than thirteen hotels. If the time that it takes some of Her Majesty’s

subjects to pass one hotel be any indication of the time necessary for

the inspector to perform his important duties, his office could not have

been a sinecure. Still the office had its advantages altogether outside

of the salary and social standing it was supposed to confer on the

recipient of the distinguished position. It was his privilege to inspect

the various liquors at any time, as well as to sample every bottle in

the bar, to enable him to decide whether they were up to the required

standard or not. It will thus be seen that a person holding the

honorable position of inspector had a difficult task to perform among

the thirteen houses of public entertainment, and preserve the dignity of

his office.

In 1862 he met a great

misfortune in the loss of his wife. They had lived happily together, and

had seen their children grow up around them respected and respectable.

The family consisted of James, in New Zealand; John, in Manitoba; Henry,

on the old homestead; Eliza (Mrs. Harding), at Fordwich; Rachael (Mrs.

Connelly), at Trowbridge; Mary Ann (Mrs. Whaley), died in Manitoba;

Charlotte (Mrs. Davis), died in Logan; and Agnes, also dead.

SOCIAL AND MUNICIPAL

Mr. Switzer took an

active part in the organization of the Blanshard Agricultural Society,

and ever since its inception has been one of its most active supporters.

During the whole period the society has been in existence he has been an

officer; for a number of years president, always a director, until three

or four years ago he resigned, when the society, as a mark of approval

for his distinguished services, elected him an honorary director. In

that position he is the first and only one on which the distinction was

ever conferred.

Early in the sixties a

change was made by Government in the law regarding the militia in the

rural districts. Blanshard was divided into two sections, the square

township forming one, and the gore part another. The late T. B. Guest

was major, and appointed Mr. Switzer as captain of the first district,

embracing the square township. The first time the writer ever met the

subject of this sketch was in the winter shortly after his appointment

to that office. On a cold morning in the month of February, we saw a

strange gentleman driving toward our shanty in the piece of clearing we

made, with rather a good-looking horse and cutter. On meeting this

person he introduced himself as Reuben Switzer, of Blanshard, that he

had been appointed captain in the sedentary force, and was desirous that

I should accept the office of lieutenant, for which position I had been

recommended to him by Mr. James Dinsmore. Mr. Switzer at this time was

rather above the average size, straight, well made, and active looking.

His features were regular and his hair, which was long and heavy, was as

white as the snow, which gave him altogether a striking appearance. It

is pleasing here also to state that the friendship which sprang up on

that occasion has continued, without a a single cloud having passed over

it, since, a period of nearly thirty years. In 1876 he took an active

part in the organization of the Blanshard Mutual Fire Insurance Company.

He has for some years been president of this institution, and has sat as

a member of the Board of Directors ever since its inception. Mr. Switzer

has been for nearly seventy years a member of the Orange Order, making

him almost the oldest, if not the very oldest, member of the society in

Canada.

He is to-day, at the

age of eighty-six years, most enthusiastic in his attachment to its

teachings. He first became a member of the Order in 1830, when he was 17

years old, and on his arrival in Canada in 1846, he organized the Lodge

on the Mitchell Road, No. 384, the first Orange Lodge in the township.

For over fifty years he has never failed on a single occasion to testify

publicly his unswerving loyalty to the Order by joining in the

procession of the brethren on the 12th. After organizing No. 384, he was

elected its first Master, and retained that position for nine years.

Since he first came to Canada he has occupied a prominent position in

the institution, and has attended a greater number of Provincial Lodges

than perhaps any other member of the Order in this section of the

country. He filled the office of the District Master for two years,

County Master for several years, was delegate to Provincial Lodges held

in almost every section of the province, and in 1896 was appointed

delegate to the Supreme Grand Lodge at Collingwood, in 1897 at Windsor,

in 1898 at Ottawa, in 1899 at Barrie. At these various gatherings of the

highest Court of the Order in Canada he is frequently honored with a

seat on the platform next to the Supreme Grand Master, as a recognition

of his distinguished services in connection with the institution. As

might be expected, Mr. Switzer has been a lifelong supporter of the

Conservative party and a most enthusiastic believer in all the actions

of the late Sir John Macdonald. He has held the appointment of treasurer

of the County Conservative Association since it was organized, and has

also been treasurer of the Conservative Association of the township

since its inception. He rarely, however, talks politics, and is never

offensive to opponents in the discussion of party questions. His great

good nature manifests itself here, as it does in his every-day life, and

his Reform friends in the township are numerous and influential. In

religion he adheres to the Methodist church, although I believe he is

not a member of any religious body. As a farmer he was fairly well up in

his calling, and has the honor of fatting the first animal that ever

left the township for the English market, and which was sold to the firm

of Robson & Sparling many years ago. In 1865 he married Mrs. Isabella

Harding, widow of the late Mr. Harding, who resided on lot 8, on the 2nd

concession. This lady had four sons at the time of her marriage to Mr.

Switzer—Rev. Philip Harding, of Ohio ; Thomas Harding, on the old

homestead; Samuel, of Port Rowan, editor of the News-Record; and

Richard, in British Columbia. Mrs. Switzer died several years ago, and

the old gentleman is again left alone. He is an honest man, and has

discharged his duties as a citizen of Canada in such a way as should be

an example to younger men. The kind old man is bending low under the

weight of his eighty-six years, yet his heart seems buoyant as ever. His

manner is as jovial and free as it was when we first met him thirty

years ago. His long white hair is still abundant, his step is as firm as

it was in his youth, but he has many evidences, distinctly marked,

indicating that he has passed the four score. We trust, however, that

time will deal gently with him in the future as it has done in the past,

and that he may yet, for many years to come, meet his numerous friends

in those haunts in which he delights to meet them, and where the cares

of life can be for a time hidden away beneath the mantle of good

fellowship. |