|

Hence we may learn

That though it be a grand and comely thing

To be unhappy (and we think it is,

Because so many grand and clever folk

Have found out reasons for unhappiness)

. . . Yet since we are not grand—

O, not at all, and as for cleverness

That may or may not be— it is well

For us to be as happy as we can!”

—Jean Ingelow.

THE following spring

mother removed from Toronto to her home in Muskoka, and by this time

things were in better shape at the new boarding-house, and in

consequence they did a much larger business during the season. In fact,

for a short time the house was fairly packed with visitors. Camp-beds,

sofas, and even the parlor floor, were used for sleeping accommodation.

Those were the days when people visiting Muskoka were thankful for small

mercies and did not look to find all the comforts and conveniences of

the large city hotels in this new country- At the close of this

successful season mother conceived the idea of inviting a party of her

Toronto friends to spend a few days and see the beauties of the Muskoka

lakes. It was the beginning of September, and I always think September

is the ideal month for Muskoka; it is not too hot, there are no

mosquitoes to bother one as in the spring, and the foliage is just

beginning to assume its lovely fall tints.

These little September parties were repeated, year after year, so long

as my dear, hospitable mother lived. I believe they were the most

enjoyable times of her life. What delight she took in showing the new

comers around her domains, in calling upon them to admire all the

changing beauties of lake and sky and shore. Of course, she liked to

have all her children there, if possible, and as time rolled on, many

small grandchildren were added to these annual gatherings.

Then the dear grandmother had something more to expatiate upon, as well

as the beauties of the landscape, namely the bright eyes and rosy cheeks

of her children’s children; and no one could wax more eloquent than she

on this exhaustless theme. What better can we wish for these dear

children than that the good wishes and earnest prayers of their dear

grandmother on their behalf may in the future be fulfilled?

Perhaps the first of these September parties is impressed most

distinctly on my mind, because I was, in a way, the chaperon of the

band. I think there were about fifteen invited, and we met that Monday

morning at the little station behind the Market. It was then I

discovered that, strange to say, not one of the crowd, except myself,

had ever seen Muskoka; so fancy my delight in acting as guide into such

a fairyland. Our minister and his wife and daughter were amongst the

party. We were all in a very happy mood, bent on enjoyment, and in full

expectation of a good time. By the time we got to Allanualc we were

beginning to feel hungry, so reached out the lunch baskets and, with

sandwiches, cake and fruit, had a nice little picnic on the cars. We

could not induce the minister, however, to take anything, for I had

informed them all of the nice dinner we would get on the boat as soon as

we arrived at Muskoka Wharf, and he said, while pacing up and down the

length of the car, “I am not going to spoil my appetite for that fine

dinner Miss Hathaway has been telling us of by eating now, don’t you

think it”; and he said it so emphatically that he made a convert of

another gentleman of the party, who also refused to touch or taste. We

remarked, though, that they both began to look very hungry and anxious

before we reached Gravenhurst, and here the joke came in. When we

reached the wharf we found only a small steamer awaiting us instead of

the Nipissing that we expected; and, on enquiry, we found the Nipissing

had been burned a few days before—a great misfortune, especially to us

just then, for there was no dinner, no dining-room, and we would have to

transfer to another boat at Port Carling, making it very late before we

would roach our destination. Our smiles and laughter were changed to

looks of dismay as we received this unpleasant information. Even we, who

had helped to empty the lunch-baskets, were feeling hungry again; what

then must have been the feelings of the two who had so rigidly abstained

? When we got on board and knew the worst, namely, that there were no

provisions to be got, we bewailed our fate to each other for awhile,

then tightened our belts, sat down, and tried to forget we were

hungry-But, as the poet remarks, “a change had come o’er the spirit of

the dream.” and we felt we had hardly energy enough to admire the

beautiful scenery through which we were passing. After a time an idea

crossed my mind, but I kept it to myself for fear of further

disappointment.

Surely the men who worked the boat must eat, likewise they must drink.

Then there might possibly be tea on board. I was just longing for a cup

of tea, and the day was warm. I slipped away to see what I could do. I

climbed down a narrow stair leading to the engine-room, and then peeped

through a square hole in the partition. Goodness! what did I behold?

There sat the minister and his friend, side by side, on a little shelf,

a board in front of them serving as a table. They each had a big bone in

their hands and were gnawing away for all they w ere worth, the

perspiration streaming off their faces with the heat of the little place

they were in. It appears my “happy thought” had struck them also, but

somewhat earlier, and they had stolen to this spot quietly and secretly,

where they found a big pot, with the remains of a stewed shin of beef,

which they had appropriated and proceeded to enjoy. When one of the boat

hands appeared on the scene, they used bribery and corruption to obtain

addition to the beef bones, a supply of bread and a kettle of tea. Their

consternation was great when they saw my face gazing in at them, for

they thought the whole party were at my heels. I revenged myself for

their duplicity by bearing off the kettle of tea. There were only two

cups on board, though, so we drank it out of all the odd tins and pans

the men could hunt up for us. The scene was so comical, when the crowd

were all swallowing the hot tea out of such odd drinking vessels (I

think even the frying-pan was pressed into the service), that we forgot,

amidst the laughter and fun, the loss of our dinner, and good-humor and

contentment were happily restored.

It was nearing sunset as we came round the bend of the river in view of

Port Carling. We were all crowded in front of the little steamer,

awaiting the first glimpse of the place, and as we drew nearer we saw my

dear mother and sisters, who had come thus far to meet us, standing

together on the wharf. Our minister was the first to see them, and,

taking off his hat and waving it in the air, shouted, "There’s the

mother,” and then, as if to give vent to his feelings, started singing,

“We’ve reached the land

of corn and wine,”

in which one after

another joined, until we arrived at the wharf, amidst a full chorus of—

“Oh, Beulah land,

Sweet Beulah land,

As on thy highest mount I stand.”

Ah me ! when we look

hack on those happy scenes of by-gone flays, no wonder that our hearts

are full of tender memories, and that, still quoting from the same

verse,

“I look away across the

sea.

Where mansions are prepared for me,

And view the shining glory shore,

My heav’n, my home for evermore.”

After we had ail

received a loving greeting and hearty welcome from my mother, we

hastened to crowd into the little boat which was to carry us up Lake

Joseph. The evening was a lovely' one. the sunset something

indescribable, and our friends were charmed with each fresh view as our

little boat puffed along its winding course. By the time we reached

Hathaway’s Bay it was nearly dark. Here my father received us, and one

of the party called out to him, “Here are your unprofitable boarders, Mr,

Hathaway.”

I can safely say a more hungry crowd never set foot in his house. How we

cleared those tables! Everything seemed so good, it was hard indeed to

stop eating. “Oh! this hoine-baked bread,” “Oh! this fresh butter,” and

such-like exclamations from all the party, as they indulged in another

and yet another slice, until we lay back in our chairs exhausted.

Of course, after such a supper we went to bed and slept like tops. Where

does anyone sleep like they do in Muskoka? There might be a narcotic in

the air, from the effect it has upon a stranger. For the first two or

three days you feel like nodding all the time, except when you are

eating ; as soon as you sit down, or lie down, you are soothed off into

slumber-land before you know' it. Of course this effect soon passes away

or it would be serious for the dwellers in the land. Work would remain

at a standstill if this drowsiness became chronic.

The days of our holiday, however, passed so quickly that we did out best

to keep wide awake and enjoy everything we could. One day my father and

mother got a small steamer and took some of the party to Bala for a

day’s fishing. There were still a few of the summer boarders in the

house, amongst them a Dr Carrington from New York, with his wife. She

was a gigantic woman, not only immensely stout, but tall in proportion.

When I first saw her I was thunderstruck, and said to mother, “Is that

Barnum’s fat woman out for a holiday? She must have been sent here to

‘recuperate her physique.’” Her hair, which was gray, she wore frizzed

and combed out, till it made her head appear enormous, and she was

profusely ornamented with chains, rings and bracelets, the two latter

kinds of adornments bei tig nearly buried in rolls of fat When she

entered the dining-room, gorgeously apparelled, sailing along, her

husband invisible in the rear, every eye would follow her as she moved

slowly and majestically to her seat. We had two stout ladies in our

party, but they sank into utter insignificance and looked like infants

beside Mrs. Carrington. With all her magnificence she proved to be very

agreeable, and we all soon got very friendly with her.

Now, my mother was very anxious to show her friends around Lake Joseph

before their return, so we planned a picnic to Cliff Rock, making a tour

of the lake in the first place and landing there for dinner. Everyone in

the house was to go, so, of course, we had to invite Mrs. Carrington,

bur how to get her there was the question. Mr. Roberts, my

brother-in-law, said it would not be safe to put her in the little

steamer, as. if she moved to one side or leaned over, she would upset

it; besides the boat was too small to carry the whole of our party. So

he arranged to get a barge, and the small steamboat would tow us. In the

very centre of the barge he planted Mrs. Carrington’s chair. I forgot to

tell you she brought her own chair, ours were not comfortable for her,

and so frail. In this chair was seated Mrs. Carrington ; then two large

rocking-chairs, one in front of her and one behind, accommodated the

other two stout ladies. They were thus planted in a row down the centre

of the barge, and, with such good ballast to steady us, we ordinary

sized mortals were allowed to disperse ourselves around as wre pleased.

We arranged to proceed slowly, calling at two or three places where fish

were reported to be plentiful, so that the fishermen of our party might

secure enough for our dinner. We had a boat in tow, and in this they

went ashore at the different places. They had very good luck in fishing,

too, so that we had a fine stock on board by noon, when we arrived at

Cliff Rock, where we landed and prepared our dinner. We did not attempt

to land Mrs. Carrington, though : her dinner was carried to her on the

barge. Bet was cook, the young ones gathered the sticks and lit the

fire, the kettle was slung on, and the big frying-pan brought out for

the fish Mother and Sue sliced up the cucumbers, Winnie laid the cloth,

and I sat down at a little distance off to make a sketch of the rock ; I

had brought my paint-box for the purpose. The day was perfect, the water

calm and the reflections lovely, so it was a pleasant task. As I was

busily working I heard someone calling my name, as if from the sky, and

on looking up I saw two of the party, our old friends Mr. and Mrs.

Francis, who had gone round through the woods and climbed to the very

top of the rock, and were now gazing down on us. I shouted up to them to

keep still and 1 would put them in the picture. I have the little sketch

yet, though many of those who were first and foremost in the fun that

day have bidden a last farewell to the fair scenes of this earth.

Has it never struck you with a kind of strange mockery, when

accidentally you came across little trifles which were associated with

bygone days and those you have loved and lost, how strange it is that

these unimportant things, of no value whatever, remain unchanged, while

our dearest and bent, so infinitely more precious, have vanished from

our sight?

But my moralizings are brought to a sudden stop by a most frightful din.

Bet is beating a tin tray vigorously with a stick, to announce that

dinner is ready, and the wanderers arc flocking in from all directions,

so I put away my work and join the crowd. I don’t believe one ever knows

bow good fish can taste till they eat it in Muskoka, freshly caught,

fried crisp and brown—a veritable feast for the gods!

I won’t tell you how many fish we ate that day, you might not believe me

; enough to say, we all ate our fill and were satisfied. Soon after

three o clock, Mi. Roberts announced that the wind was changing, and it

was likely to be rough on the lake, so we had better prepare for our

return.

We had great fun in the

embarkation, for all the ladies who had been wandering in the woods

returned with such loads of treasures—moss, ferns, birch bark, fungi,

and such like—that it was quite a job getting all the stuff stowed away

on board to the satisfaction of the fair owners. At last, however, we

were ready, the “stout ladies” all in position, and once more we were on

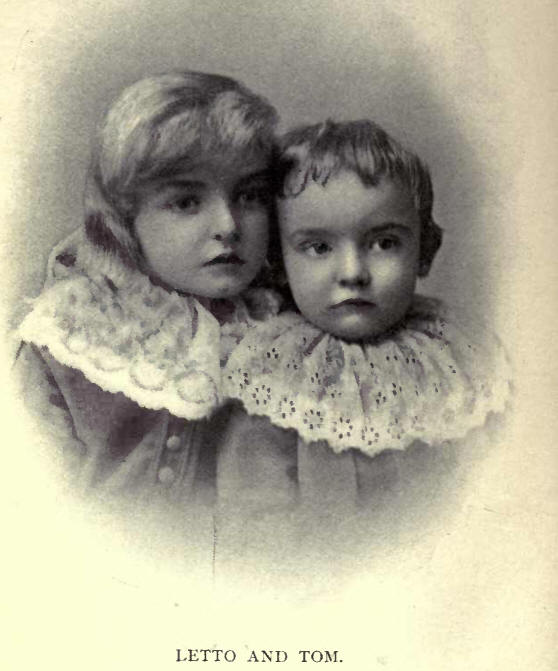

the move. Winnie put me in charge of my two little nephews, Letto and

Tom, who were very anxious to fish over the edge of the barge. They had

pieces of string tied to sticks, with crooked pins for hooks. It was

hard work holding on to them both, and I was getting a little tired,

when one of the gentlemen of the party, who had been fishing and was

sitting next to Letto, signed to me to turn the children’s attention in

another direction for a moment, and meanwhile he slipped a good-sized

fish from his basket on to the crooked pin at the end of Letto’s line,

then let it quietly drop into the water, As soon as the child turned

round he cried out, Oh, my! Letto! look at the fish on your hook,” and

helped the delighted youngster to pull it up. What an excitement ensued.

The children were wild u'th delight; they tore across the barge to their

mother, then to their father, and everyone else in succession. They

hugged that precious fish, and mauled it. they patted and pulled it,

they nursed it by turns; pressing it fondly to their hearts, they would

not part with it, and even wanted to take it to bed with them, so Winnie

said, and they smelled fishy for days after.

Letto has never forgotten that fish and never will, if he lives for a

century.

The wind blew very strong, as Mr. Roberts foretold, before we reached

home, and the barge bobbed up and down in fine style. Mrs. Francis lost

her hat. a sudden gust carrying it far away over the water Sue’s

husband, who was, as I told you, the smart man of the family, sprang to

the rescue, jumped into the boat and was after it like a flash. We could

see him making straight for the little black speck in the distance, and

in a few minutes he returned triumphant bearing the hat. a sorry-looking

article surely, feathers and lace all dripping; but the good-natured

owner took it all in good part, and tying a handkerchief over her head,

said it didn't matter much, for she hadn't been so foolish as to come to

a picnic in her best hat. We were soon safely back at Hathawray’s Bay

and the ladies busy landing their treasures from the woods. Thus ended

one of the happiest days of our lives. |