|

“Look there! look there!

now he’s up in the air,

Now he’s here, now he's there,

Now he’s no one knows where:

See, see! he’s kicked over a table and chair.

There they go, all the strawberries, flowers, and sweet herbs,

Turned o’er and o’er, down on the floor,

Every caper he cuts, oversets or disturbs.”

—“Ingoldsby Legends."

WHEN I was a young girl

in the Old Country I was once complaining to an old aunt of my father’s

of the whims and vagaries of my younger brothers and sisters, of how one

was selfish, and another cross, until she, wise woman, stopped me,

saying, in a serious tone, “How many are there of you, Nan?” I answered,

“Six.” “Oh!” she replied, “you are just one of six; now you must not

forget that each one of those six children possesses an entirely

different individuality; that each one has his or her special faults and

failings, also virtues. My advice to you, dear Nannie, is to look for

their good qualities instead of their defects. You know what a wise man

once said to me, ‘Never look too hard, except for something agreeable;

you can find all the disagreeable things in the world between your hat

and your boots.’”

Dear old aunt, I thought she was rather severe upon me at the time, but

her words were never forgotten, and perhaps it was due to pondering over

her remarks that I acquired the habit of noticing the marked differences

we constantly observe between brothers and sisters, children of the same

parents, associating constantly with the same people, brought up in the

same home, yet developing into characters so widely divergent, and in

all their tastes so far apart. This habit, which has grown stronger with

years, led me on to become intensely interested in another subject, that

of heredity, with which it is closely associated. What a marvellous

thing it seems that enclosed in the form of that tiny baby are

unnumbered traits, not only of feature but of character, inherited from

generations of ancestors, all differing from each other, and yet

everyone bearing in mind and body the family stamp in a greater or

lesser degree.

I think it was in the Toronto street-cars I made most of my studies in

this line. I had numberless opportunities riding back and forth to

business, and an endless and constantly changing series of faces to

observe, so I used to amuse myself with studying those within my

range—perhaps it would be father, mother and children, and you would see

a little girl a small miniature of the male parent, a small boy labelled

“mother” all over, or still another child a curious mixture of both

parents. I have often seen a group of three generations, perhaps the

careful grandmother going shopping with her married daughter,

accompanied by various young olive branches, where you might chance to

find the same face in three different stages of existence—childhood,

womanhood, old age.

Another curious fact is, that these striking family resemblances are

most observable by complete strangers, or by friends who have been

absent from us for a considerable length of time. I will give you an

instance of this which occurred to me a few years ago. I was sitting

with a friend on the verandah at Hathaway's Bay, watching the departure

of the morning boat, when a complete stranger, a lady who was sitting

near me, evidently an American, turned at the sound of my voice, and

looking me full in the face, said, “Surely you are one of the Hathaways

” "Yes,” I said, "I am Mr. Hathaway’s eldest daughter.” “Oh.” she

continued, still gazing at me, “but you are like your grandfather.” “My

father, you mean,” I replied, for I knew it was impossible she could

have known my grandfather, who died in England years ago. “No,” she

still affirmed, “I mean your grandfather,” and then she explained that

in the parlor she had seen an oil painting of my grandfather, which had

been brought from England to this country after his death.

I said to the friend who was sitting with me, “Come, let us go and look

at the picture, for I had no idea, often as I had seen it, that I

resembled it in any way, and I was anxious to see the likeness for

myself, and whether it was truly so startling. Strange to say, we could

both see it very plainly. I don’t believe it was there in my youth, but

as I grew older the latent resemblance, unnoticed until now. must have

increased, so that since then, whenever I look in the mirror, I can see

it plainly—my dear old grandfather’s face in my own But you will be

saying, what has all this to do with Tom? Tormenting Tom! Well, I am

coming to him now. I have told you of Muskoka tourists, Muskoka

settlers, now the next two chapters will be about something far more

interesting—to me, at least—namely, Muskoka children.

I have not far to go to find them, for Winnie is just across the road

with her six; though Letto, my eldest nephew, would not care for me

calling him a child—he is a young man now, tall and fair, with a

suspicion of a mustache, Letto is the favorite with all the children,

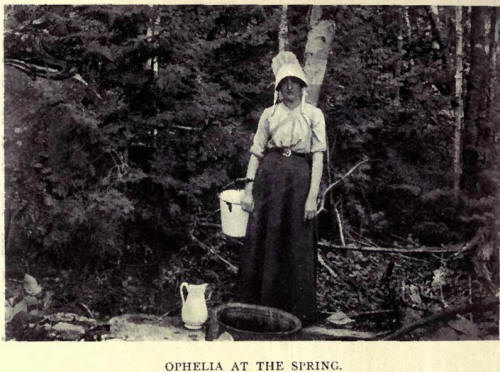

for he is so gentle and good-natured. Tom is Winnie’s second son, and of

quite a different stamp. Then follows the gentle Ophelia, the only

girl—who is, like Letto, tall and fair, and has the pathetic droop in

the corners of her mouth which makes her resemble her Shakespearean

namesake. But it is of Tom this chapter is to tell, so here goes. Tom

arrived in this world a thoroughbred Hathaway, not a trace in him of the

gentle Letto, who belonged entirely to the Roberts’ side of the house;

but Tormenting Tom was a rampant, roaring Hathaway. Winnie knew it when

she heard the first loud cry from his expanding lungs, and as he grew

and developed, we arrived at the conclusion that all the energy,

destructiveness and mischievous qualities of many generations cf dead

and gone Hathaways must be concentrated in that small boy.

Unlike Letto, who had

been an angelic baby, Tom was never at rest. He had a large head, which

was perfectly bald till he was about a year old, though his mother was

always anxiously looking over it to see if there were any signs

of sprouting hair. This big head of his was always getting bumped ;

being the most prominent part of his body, it appeared to be always in

the way. When he was about eight months old, Winnie brought them both

down with her on a visit to the city. Sue’s little boy was then about

six months old, and was the happy possessor of a baby carriage and a

small nurse-maid. Sue good-naturedly made the offer to put another

little seat in the perambulator so that Master Tom could share her

baby’s daily promenade.

Well do I remember the first start after the carriage had been fixed. We

all proceeded out to the sidewalk to place Master Tom in position. The

babies were to face one another, and Winnie carefully seated Tom

opposite his small cousin. The two glared at each other for a moment,

then Tom, with a howl of rage, threw himself forward, snatched the other

baby’s hat off, threw it in the street, and then seizing him by the hair

with one hand did his best to scratch out his eyes with the other. We

hastily separated and endeavored to soothe the youthful pugilists, but

to no purpose. Tom s fighting blood was roused, and the double carriage

scheme had to be sorrowfully abandoned.

I think it was two years after this, and when Ophelia was a baby, that I

next saw Tom Their mother brought them all once more on a visit to Sue.

I will only tell you one little anecdote of Master Tom on this occasion;

it will serve as an illustration of his keen sense of humor and love of

imitation even at the early age of two and a half years. It was a rainy

afternoon, and to amuse the children I had given them a whole pile of

those little squares of pine used in the city for kindling. They were

happily engaged playing on the floor writh these blocks when a loud

outcry from Sue’s boy told me something was wrong. I found he had run a

small splinter into his finger, but with my needle I soon removed the

cause of the trouble, the other two gazing open-mouthed while the

operation was being performed. After a few minutes I missed Master Tom,

and, fearing he was in some mischief, I got up from my work to discover

where he was. I found him hidden in a small space between the stove and

the wall, sitting on the floor, but so intent in the performance be was

engaged in that he did not perceive me looking down on him. Fancy! the

young urchin was carefully fixing a small splinter in his own finger,

exactl> as it was in the other child’s. I said nothing, but quietly

returned to my seat to await further developments. In a few moments the

rogue emerged from his retreat extending his finger towards me with the

splinter sticking up, but holding his hand very carefully, for he had

not the courage to push it in far. i do wish you could have seen the

expression of his face ; it was most ludicrous. He was trying to screw

up his small features into a look of agony, at the same time his

twinkling eyes were full of the keenest humor. I snatched up the young

hypocrite and rolled him on the table and we both laughed till we cried.

The next scene of Tom’s youthful days which I shall relate was in

Muskoka. I was not an eyewitness, but have heard the story told so often

that I know it by heart. Churches were not numerous, nor church services

frequent in Muskoka at this time, and as Winnie’s home was away in the

bush, her third child (the little girl) was about three months old

before an opportunity presented itself of getting them baptized. She

heard then that a service was to be held in a little English church

distant three or four miles from them, on Easter Sunday, and she and Mr.

Roberts made up their minds to take the three children there. My sister

Bet and brother Ben and his wife were to act as sponsors to John Hamlet,

Thomas and the small Ophelia, in the absence of the other aunties, and

Winnie took great pains to impress on the minds of Letto and Tom for

some days before the necessity of good behaviour, assuring them they

would not be hurt, and explaining in as simple words as she could how

they must conduct themselves. She had no fear about the angelic Letto,

but her heart failed her when she looked at the sturdy Tom. Direful

forebodings of what might happen when the white-gowned minister took

hold of him filled her maternal bosom. Bet, however, laughed at her

fears, and said. “You just leave him to me and hell be all right,” which

Winnie only too gladly agreed to do. The eventful Sunday arrived, and it

was fine and warm. The walk through the woods was rather tiring, and

they were glad to reach the church and sit down Mr. Roberts took charge

of Letto. Winnie had the baby, and Tom remained under the strict

surveillance of Auntie Bet.

The baby was baptized first, and as the cold water roused her from her

peaceful slumbers her plaintive wailing so filled the church that Winnie

had to retire with her to the porch, and so escaped the concluding

scenes of the ceremony. Mr. Roberts next handed over Letto, and of

course he behaved well, though he turned very white and shook in every

limb. Now came Tom’s turn. When he saw the minister advancing towards

him he burst into a loud roar and clung to Bet’s skirts like grim death.

The clergyman, however, was not daunted, He was a muscular Christian and

not unused to such scenes, so with a mighty effort he succeeded in

detaching Tom and raising him in his. arms. The howling now was

redoubled, but the minister did his best to make his voice heard as he

proceeded with the service, Tom wildly clawing at his face and hair and

kicking for all he was worth. The climax was reached when, with his

continued struggling, Tom began to slide downwards. First his legs, then

his body, began to emerge from his garments, leaving his clothes in a

bunch round his head, and still in the strong grasp of “his reverence.”

Bet said she stood it to this point, but when she saw Tom’s body

emerging from his clothes, his legs striking out in every direction like

the sails of a windmill, and the clergyman, the perspiration standing on

his brow, but still holding on and saying at the top of his voice, “

Fighting manfully under his banner,” it was too much even for

equanimity, and she stuffed her handkerchief into hei mouth and, bowing

her head, tried to hide her inward convulsions of mirth. I am always

thankful I was not present; goodness knows how I might have conducted

myself. Tom, being at last released, flew to his mother in the porch,

they all heaved a sigh of relief, and the service was concluded in

peace.

Tom was a great boy for his mother—rarely could he be tempted from her

side. Letto from a baby would be good with anybody, but Tom was iust the

reverse. He was also the most profuse weeper it was ever my lot to meet

He literally shed floods of tears they rained over his face in perfect

streams. I used to wonder wherever they came from, the fountain

appearing inexhaustible His mother had fairly to steal away from him

when she wished to go anywhere. Once I remember she brought them both

with her to my father’s, and left them with us while she went over to

the island at the mouth of the bay to spend the morning gathering

huckleberries. Tom did not miss her for about an hour, and then there

was a great outcry; nothing could pacify him, the tears flowed in

torrents, and it seemed impossible to staunch the flood.

At last my father, unable to stand it any longer, bethought him of a

pair of field-glasses which he had put away in a box. He got them out

and adjusted them, then went to the front of the house to find out

whether he could see Winnie. Yes! there she was, picking away on the

island. He called Master Tom. “Now, then, come here! Will you be good if

I show you your mother? Will you stop that roaring if you can see her

with your own eyes?” Tom promised, and father held the glasses to his

eyes. Ah ' how his face changed when he saw the beloved form through the

magic glass. Yes! there was mother right enough, but as father took away

the glasses she disappeared, and again the cries burst forth. “She’s

gone! She’s gone!” Once more the magic machine was brought forth, and

Tom again satisfied himself of her presence; once more, on withdrawing

his eyes, she vanished; and so it went on until at last to our great

delight we saw Winnie get into the boat and start for home.

As Tom grew up he

developed a strong taste for teasing; he seemed always on the watch for

any opportunity of tormenting the younger ones. There was a continual

cry in the house, and out of it, too, of “Oh, Tom!” “Stop, Tom!” “For

shame, Tom!” I could fill a book with stories of his tricks, but as I

have some other children to tell you about I will leave Tom for the

present. You will hear of him again, maybe, in the future.

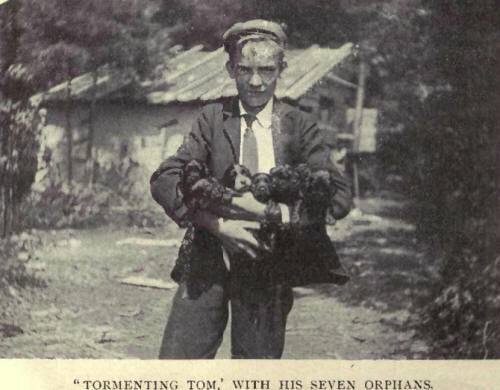

But I am forgetting to explain the picture of Tom with his seven

puppies. He vias a great lover of animals, and though he delighted to

tease them, was never cruel, especially to the weak and helpless. He was

always encountering stray dogs and bringing them home, thereby bringing

down on his head the wrath of his mother, who declared she would not

have her house turned into an asylum for waifs and strays.

Once when Tom was sent on an errand to a neighbor’s he was taken to see

seven puppies, who were only a few weeks old. Thinking to play a trick

on his mother, he begged the owner to lend them to him for a short time,

and then proceeded home with his load. Entering the house he called out,

“Don’t be cross, mother, but I have adopted seven little orphans.”

“Orphans?” said Winnie, coming forward, and then she spied the seven

little dogs. Oh, goodness! how she went on, and Tom drawing her out,

combatting all objections, till he had her nearly furious, the villain.

While the controversy was at its height a young lady visitor, unknown to

Master Tom, took a snap-shot of him and then gave it to me. He will be

rather astonished when he sees his picture in this book. But serve him

right, say I. |