|

“Make but my name thy

love

Ami love that still,

And then thou lovst me,

For my name is Will."

—Shakespear Sonnets.

“HAVE I got to die,

Auntie Nannie? Gladys! says I must die.” Fancy a small earnest face

upturned to yours, gazing at you with two serious blue eyes belonging to

a little man just four years old. Such a question from a child? For a

moment I was puzzled how to reply, and taking him on my knee I said,

“Why Willie, I hope you will live for a long, long time, and grow up to

be a good man and be very happy and have lots of people to love you.”

“But have I got to die?” again earnestly asked the child, and not

knowing what had filled his mind with such a subject I called to his

little cousin, Ben’s youngest girl, with whom he had been playing in the

next room, and asked her what she had been saying to Willie. She,

hanging her head and looking rather shame faced, replied hurriedly,

“Well, I told him everybody in the world had got to die, and he would

have to die too some day sure, just like my little bunny rabbit, but 1

didn’t ezackly know which day; and he’ll be put in a hole in the ground

and be covered with leaves like the babes in the wood.”

I looked at the two children, such a complete contrast. Gladys, a

dark-haired, rosy-cheeked, sturdy little maiden of seven, her eyes

sparkling, and whole being bubbling over with life and energy. Willie,

frail, delicate, spirituelle, his small white face so transparent that

every thought of his intensely active brain seemed mirrored on its

surface. 1 never saw a face in which the action of the mind could be so

easily read. “Mind” and “Matter’’ this small pair of cousins might be

aptly named.

I thought my wisest plan was to endeavor to turn their attention to some

other subject, and succeeded for a time, but Willie was evidently deeply

impressed. The thoughtless word of his playmate had taken a strong hold

of his imagination, and when half an hour later a visitor came in, a

lady whom he knew well, he ran up to her at once, saying “Have I got to

die?” The lady, rather startled, looked to me for explanation, which I

gave her after I had sent the children away to play. Winnie told me that

his first words on reaching home that evening were “Mother, have I got

to die?” Dear little Willie. Death overshadowed him even before his

birth, for he was born only a few weeks after we had lost our dear

father, and while our hearts were still sore from the shock of our

mother’s death. No wonder that he had a hard fight for life, the

darling, and that his little body is so frail and his face so white. But

God heard his mother’s prayers and spared her boy, and the months and

years of his short life have served but to enshrine him ever deeper in

our hearts. Since “Auntie Nan” arrived here she has enjoyed (he

distinction of being one of his prime favorites, and “Old Maid’s Lodge”

is his second home.

Willie was born on the day his brother Ephraim was seven years old, and

Winnie always calls them her twins. Bet, who was staying there for the

occasion, describes their first meeting: “The children were all away at

school when Willie was born, but when they came home to dinner she

called Ephraim (who was my father’s namesake) and told him to come

upstairs; and when he arrived she placed the baby in his arms saying,

“There is your birthday present.” Poor boy, he turned first red and then

white; the surprise was so great he was quite overcome, but it gave him

a sense of ownership as regards the baby. Ever after he called Willie

“my infant,” and would come in from school every day asking “How is my

infant?" And the “twins” to this day remain the most loving of comrades.

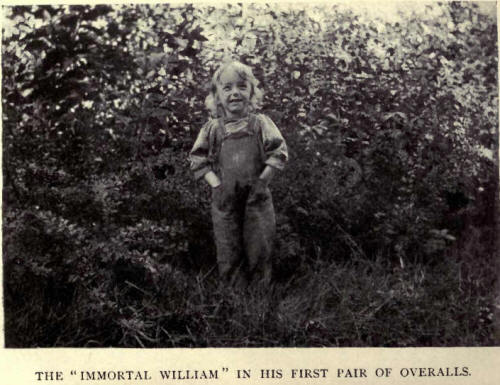

Before we go any further I must explain to you, for fear there should be

any mistake, that the “Immortal William” is not named after William.

Prince of Orange. No! to English people, and especially Warwickshire

people, there is only one William and that is the “Immortal

Shakespeare.’’ Not but that I have the greatest respect for the “Orange

William,” though I hardly ever heard his name till 1 came to this

country and lived in Toronto, where the great procession of Orangemen on

the twelfth of July was quite a revelation to me. How my heart throbbed

with pride as I saw those hundreds of mer. marching along with the bands

of music, the banners and the flowers; above all, the open Bible carried

through the streets with the glorious motto waving above it, “Protestant

rights we will maintain.” How it thrilled through my very being, for I

am a “Protestant of the Protestants,” and glory in the name. Born of a

long line of sturdy “independent” ancestry, our family motto has ever

been “ for faith and freedom and in this new land of our adoption, which

is happily free from so many ecclesiastical swaddling-bands and rags of

ancient mummery, let us ever uphold the Divine freedom of man and “equal

rights to all.”

But to return to little Willie. He visits me nearly every day, and

generally arrives soon after breakfast, walking, if fine, or if wet or

snowy hoisted on the shoulder of one of the older branches of the

family. This morning he greeted me with the question, “Auntie, am I a

nuisance?” “No; who said such a thing to you, Willie?” “Well, mamma said

when I wanted Letto to carry me over here dreck’ly after brexfus’, that

I must be a nuisance to you, I’m not a nuisance, am I, auntie?”

regarding me with most imploring eyes. “No. my darling; tell her you are

my greatest blessing; I couldn’t do without you,” and immediately his

face assumed an expression of supreme content. He is the greatest little

questioner, and gives me no peace; one subject succeeds another. Last

week it was colors. What color is this? What color is that? “What color

is the sky?” “Blue.”

“What color is my dress?” “Blue, too.” “Well,” looking from the sky to

his dark blue frock with a puzzled look, “they are not alike” “No, your

dress is navy blue.” A long pause, eyes fixed graveiy on the dress, then

extending his legs, intently surveying them, “And are my stockings gravy

blue, too ’”

To-day he arrived greatly worked up about the meaning of the word

to-morrow. He burst out indignantly, “When is it s’morrow? They all keep

saying ‘ s’morrow and s’morrow,’ and when I get up in the morning I say,

Now it’s s’morrow, and they say, 'No, it’s s’morning.’ Then after dinner

I say, Now, is it s’morrow? and they say, ‘No, it’s s’afternoon.’ When

is s’morrow? That’s what I want to know.” I leave to my philosophical

readers the answer to this question.

He is getting pretty well acquainted with the days of the week. His

beloved twin stays horn: Saturday—no school; then he learnt it was the

next day to Friday, and Sunday came after the holiday, and so on. But

the months of the year are rather more trouble. The future is always

September. “The violets will bloom—in September.” “The chickens will

hatch—in September.” “Santa Claus will come—in September.” “I will be a

big man— in September,” and so on ad libitum.

Willie for the most part of the time has to play alone, for Ephraim is

at school. He is therefore indebted to his own inventive brains for

means of amusement. His father keeps a horse, cow and pig, and these

animals are most attentively watched and copied by the Immortal William.

Their every action is studied and imitated to perfection. He takes turns

in representing the various animals. He is generally accosted on his

arrival in the morning with the question, “Well, what are you to-day,

Willie?” and the reply is, I am a cow, or horse, or perhaps a colt, as

the case may be. Then every action of the chosen animal is faithfully

and cleverly represented. Honestly, I, being a greenhorn, have become

familiar with all the motions of the animals, not from my own

observations of them, but from Willie’s antics. Often I fairly laugh

aloud as I pass cows and horses on the roadside and see them making

exactly the movements which Willie has gone through for our amusement.

To see him lick his shoulder, toss his head, kick up his heel, chew his

cud, is really too ridiculous.

Of course, if he is horse or cow, after simply announcing the fact the

rest is all dumb show. You might ask him a dozen questions, but the only

reply would be a toss of the head, a whinny or a moo as the case might

require. If he is a cow he must needs have a bell, also, important

still, a long tail. Anything lying around at all resembling that useful

appendage is immediately appropriated for that purpose. His mother had a

good laugh the other day. There was a lady staying there, and one

morning she, not being very well, did not get up to breakfast. Willie,

running past her bedroom door and peeping in, saw a long hair switch

lying on the dressing table. He trotted down to his mother in the

greatest state of excitement. “Oh, mamma! mamma! there’s a lovely cow’s

tail in Miss Brown’s room on the table. Oh. do ask her to lend it me. I

won’t lose it; I’ll be awful careful.” "Bless the boy,” she said, “that

would never do; it is hair; she wears it herself.” “Wears it herself!”

he replied, gazing at her with eyes wide with astonishment, “what does

she want with a tail? Shes no cow,” (the last with great scorn.) “Do ask

her to lend it me, mamma, just for one day.” Poor Willie! she had to

send him away quite cast down. She would not have had Miss Brown know of

Willie’s longing desires for anything, because she was rather a touchy

person, and for the next day or two Winnie fairly trembled at meal times

when she saw the child’s eyes, full of admiration, steadfastly fixed on

the summit of Miss

Brown’s cranium, whereon reposed in all its glossy stateliness the much

coveted cow’s tail Wiilie, after recovering from his disappointment,

turned his thoughts and ambition in another direction, and one day, soon

after, came to his mother with two or three pieces of rag rolled up like

small sausages, and wanted them sewed down the front of his little

dress. After this was done he ran outside, falling on all fours on the

grass, calling out as he did so, “Now, I'm the cow; just come and milk

me!” This milking proved a serious business: being a novelty, every one

was pressed into the service, till the thing got rather monotonous,

except to the young cow, who would come sometimes, almost in tears,

saying to Winnie, "Ephraim won’t milk me”; and when she appealed to the

recreant he would toss his head and say, “I can’t be milking him all the

time,” so the poor little cow had sometimes to remain unmilked.

When Willie personated a horse he always wanted work, so he used to draw

chips on a tiny sleigh and bring them into the kitchen, always waiting

patiently, if I was engaged, till I was at liberty to unload them and

put them in the wood-box. This, of course, the horse never did.

Occasionally he was a frisky young colt, and then I had to personate the

old “mother horse.” I used to call the sofa the stable, and generally

coaxed the young colt to take his afternoon nap by lying down with him

by my side. Willie’s candid remarks to visitors and strangers are often

the source of amusement, though sometimes he puts us to confusion by

being anything but complimentary. He said to a maiden lady of middle age

who was here last week, and was remarking on his fondness for me,

“Wouldn’t you like to have me for an auntie, too, Willie”? she asked

him. “No!” he said, most emphatically, but after looking her over

critically for a minute, added, “I would have you for a grandmother;

grandmothers die soon, you know.” The lady looked anything but

flattered, though I tried to smooth it over by saying he had never known

his grandmother, had been told she was dead, and so he had got hold of

the idea of death in association with the name.

Another spinster, who wore spectacles, he accosted with the remark, “Do

you call yourself a young lady, Miss Jones?” “Well, yes, Willie,” she

said, bridling and coloring (for Willie had put the emphasis strongly on

the young), “I suppose I am what you might call a young lady.” “What!”

he said, “with those specs?” with the most innocent look of surprise

imaginable. Even at the risk of offending, we could not help but laugh.

Auntie Sue sent him at Christmas a book of animal pictures when he was

three years old, and these proved a source of never-ending amusement.

The questions he asks about the various animals are innumerable, and he

is quick to see the resemblance between them and human beings. The

following spring he was playing in their garden, which adjoins the

Government road, when he came running in, calling loudly, “Mamma.,

mamma! come quick, there’s a monkey just gone up the road, a great big

monkey! running so fast!" She ran to the window, and just caught a

glimpse of—what think you, my readers, you young dudes in short pants

and fancy stockings? A man on a bicycle! The first the child had ever

seen and such was his impression.

I think the monkeys in his book were the greatest favorites. There was

one big ourang-outang, standing by a stump, which greatly interested

him, and came near being the cause of serious offence to an old friend

of his father’s. This gentleman, who never shaved and was very hairy,

and also short-sighted, called at their house one day, and as he had

never seen Willie, took special notice of him, taking him on his knee

and asking him questions; Willie meanwhile fixing his eyes on him with

the expression of a snake looking at its charmer. At last the gentleman

said, “You don’t know my name, my little man, now do you?” “In course I

do,” responded Willie, promptly, for he was recovering from his shyness,

“you are the monkey man, the big hairy monkey man! I’ve got your picture

in my book, I’ll go and fetch it,” suiting the action to the word, but

his mother caught hold of him and adroitly changed the subject.

Willie’s mother is

trying to instil into his youthful mind some of the rudiments of

theology, but is often brought up short by the aptness of his replies

and the quaint ideas of his little brain. For instance, God he calls the

“Man in the sky,” and he is continually asking such questions as, “Will

the Man in the sky laugh and be glad when he sees all the wood your

little horse has drawn for you, mamma?” “Will the Man in the sky be

sorry if I cry when the soap goes in my eyes?” Satan he alludes to with

a face of awe as “that bad boy that we mustn’t say his name.”

While I am writing this he is beside me, and the questions come thick

and fast. I will close this chapter with reporting our conversation for

the next ten minutes.

I had given him two or three cards to look at to keep him quiet, but

they do not seem to have that effect. He has selected one, an Easter

card, the usual thing, angel ringing the bells, doves flying round and

so on, “Auntie, what house is this?” “That is a church.” “What is a

church, auntie?” “God’s house.” “Aren’t all the houses God’s, auntie?”

“Yes, they ought to be.” “Are all the people that go to church God’s,

too?” “Well, we hope so.” “What is this woman doing?" pointing to the

angel. “That’s an angel ringing the bells.” “Do angels always go round

in their nighties, auntie? Aren’t they cold? Do their feathers keep them

warm?” “I guess so,” I reply. A pause for a moment, followed by another

examination of the card. “What is she ringing the bells for, auntie?”

“Because it’s Easter,” I say shortly. “Are these the Easters, auntie?”

pointing to the doves. “Are all these little Easters flying round?” “No,

those are doves.” “Ducks, auntie! Can they swim?” “Doves! Doves!” I say,

rather impatiently, but no one, however crusty, can ever be vexed with

Willie; he is so sensitive to a word of blame, and so anxious to please,

that we have to be extremely careful not to hurt his feelings. If we

speak harshly to any one in his presence, even the dog, the corners of

his little mouth go down and the eyes fill with tears. But it is time I

ended this chapter, so for the present we will wish Willie good-bye. |