|

“Confound the cats! All

cats—alway—

Cats of all colors, black, white, grey,

By night a nuisance, and by day,

Confound the cats!

“Confound their saucy-looking whiskers!

Confound them, whether old, or friskers!

Confound their midnight squally discourse!

Confound the cats! ”

—Dobbin.

NO stories of life in

Muskoka would be complete without at least a few words about the members

of the feline race, who not only abound here, but are particularly

strong and active, and attain an enormous size. Why they should be much

larger than Toronto cats I cannot conceive, unless it is the fresh air,

or maybe it is their plentiful supply of mice; anyway, it is a fact the

cats are prodigious ! I never look atone of the monstrous old Toms but I

think of that verse in Genesis: “There were giants in the land in those

days.”

Now, I must confess, I am no lover of cats, never have been, though I am

an old maid. That ancient saw about cats and old maids is a fallacy. Let

me give you a living proof of this. Here is iny sister Sue, a wife and

mother, who perfectly dotes on cats; has done so ever since she was a

baby.

I remember how she used to hug and kiss our old cat at the farm in

England when we were all children. How she nursed it as her baby,

preferring it to all her dolls, which she said w ere only old dead

things, while Pussy was a real “meat baby,” alive and kicking. She used

to walk up and down the room by the hour carrying it in her arms,

wrapped in an old shawl, and singing for a lullaby, as she hushed it to

sleep.

“I love little Pussy,

her coat is so warm,

And if I don't hurt her shell do me no harm.”

It was a pretty sight

to see her, I have no doubt, and I believe there was even a suspicion of

a tear in our fond mother’s eye as she watched the little mimic and her

baby; but there was no tear in mother’s eye when, one day, she

discovered the loss of baby’s best embroidered robe and cap, and made

the discovery, after much vain searching, that they had been

appropriated by little Miss Sue, who had carefully dressed her beloved

cat in che dainty garments, and was at that very moment proudly parading

the village streets, amidst a cloud of dust, a whole tag-rag and bobtail

of envious urchins at her heels. This was the climax, and effected the

entire ruination of the “cat and baby” business.

Poor little Sue, her days of childish romance were suddenly brought to a

close, but the love of cats still lay dormant in her breast, and, years

after, in the early days of our sojourn to Toronto, when a little black

kitten ran into our house and took refuge under her bed, Sue was

determined to keep it for her own. She quieted all my mother’s

objections to the new arrival by saying that a black cat coming into a

house brought with it great good luck; that unknown and fearful

misfortunes would befall us if we dared to drive it away—all the

boarders might suddenly leave; the chimney might take fire; we might be

all burnt to death in our beds, and then we would know what it meant to

turn out a black cat. The vague idea of such dreadful events following

its eviction so scared poor mother that she yielded the point, and the

black cat took up its abode with us.

Now, I think it is owing to Sue’s persistent conduct on this occasion

that the tribe of Muskoka cats owe that strong streak of the “Old Harry”

which is so predominant in their make-up to-day; but to show the reasons

which have led me to this conclusion I must continue my story. The black

kitten grew and thrived under Sue’s loving care and protection, but as

it grew older displayed such a mischievous temperament, such a spiteful

disposition, such sad thieving propensities, that one of our male

boarders christened it “Satan.” Sue, of course, strongly objected to the

title, but it appeared so appropriate to everyone else in the house that

the name stuck, and, sad to relate, the cat never got rid of it. Well,

one fine morning we all received a startling shock. Satan undeniably

proved herself to be a lady by depositing no less than five satanic

young imps, black as herself, on Sue’s bed. Sake’s alive, wasn’t there

an uproar! But tender-hearted Sue would not hear of one of them being

drowned; was furious and dissolved herself in tears when such a thing

was even hinted at. Still, as days went on, it was plainly to be seen

that “old Satan” and five “young Satans” were too much for one house.

Even Sue could not be blind to this fact, so she concocted a pan of her

own for the disposal of them, which she craftily proceeded to put into

execution.

My father was at home just then, but only waiting till the boats began

running to return to Muskoka. The morning he went away Bet and I

accompanied him to the station, but Sue was nowhere to be found when he

wanted to wish her good-bye, which we thought very strange. However, on

our arrival at the station the mystery was solved. There sat Sue in the

waiting-room keeping watch and ward over an immense bonnet box, very

securely tied, and the lid perforated with numberless small holes, like

a gigantic pepper box. I need hardly tell you that it contained “Satan”

and her progeny. Sue had made up her mind, after many a severe struggle,

to send the whole family to Muskoka. Father fumed and raged when he

discovered the contents of the box, and swore he would never take them.

Sue was as equally determined that he should. The conflict raged for

some time, and ended by Sue mounting on the cars with her box and

depositing her precious burden by the side of father’s valise. “Now.

dad,” we heard her say. in a very coaxing tone, “don’t you always say

the mice are swarming up in Muskoka—that they worry you to death? See

what a clearance this cat will make for you, especially when the five

kittens are old enough to help her. Why, there won’t be a mouse left for

miles around.” But father was not to be coaxed. He vowed that as soon as

he got to Gravenhurst he would send the whole caboose adrift on the

lake. Fancy Satan, with her five babies, sailing around on Lake Muskoka

in a bonnet-box boat. The thought of it was too ridiculous altogether.

But even this awful threat did not deter Miss Sue from her purpose. She

talked and persuaded, and waited on the train until it was actually

moving Then she leaped off, leaving the box behind her. Bet and I quite

expected to see it come bundling after her. But it was not quite so bad

as that, and our next news of the Satanic family was that they had

reached Hathaway’s Bay in safety, and had taken to their new life in the

backwoods amazingly well.

Indeed, Bet told us, when she went up there some weeks later, that

father, strange to relate, had developed quite a fondness for Satan. I

think family cares must have had a sobering effect upon her, for she

would sit quietly on his knee in the evenings, and he would talk to her

as he smoked his pipe. They became, in fact, quite “chummy”; so, as

Shakespeare says, “All’s well that ends well.”

Of course, as I said before, the Satanic blood has infused itself into

the whole race of Muskoka cats, and I doubt whether at the present day

in the whole district there is a cat living who has not a few drops of

it in her veins. “A little leaven has leavened the whole lot.”

Now, I would give you a few of my own experiences this past winter in

the matter of cats—how I have been goaded to madness and driven nearly

to desperation by their antics; how I have vowed a solemn vow that after

I have once got rid of the animals I am now tormented with, no cat shall

abide under my roof for evermore.

When I came to Muskoka to live I discovered, as the renowned Dick

Whittington did on his travels of yore, that in Muskoka there was a

general plague; no house seemed to be exempt. It was at its worst in the

spring and fall. This plague was mice. There seemed to be mice, mice

everywhere; you could not open a drawer or a cupboard but a mouse popped

out; you discovered them at every turn “eating your cake,” ‘‘smelling

the cheese,” “drowned in the milk,” “smothered in the flour,”

“scampering over your pillow,” “floating in your wash basin.” Even your

old letters, treasured perhaps for years, and put away carefully in some

small box, you found, when you opened it to gaze on them once more,

“nothing but a mouse’s nest.”

We tried mousetraps, we tried “rough on rats.” At last the girl I had

helping me, in an unlucky moment, smuggled in a young cat, aided and

abetted in her deception by my sister Winnie, who owned the “mother cat”

and was very anxious, for certain reasons, to get rid of the “daughter

cat.” When I discovered their joint deception 1 was very irate, and

insisted at first that Ihe intruder should be restored at once to the

bosom of her mother; but Minnie pled so earnestly to keep it, and my

sister enlarged to such an extent on its valuable qualities as a "mouse

exterminator,” that in the end I was over-persuaded. The cat remained,

and from that time my troubles began.

Being young, she was also playful (that goes without saying). Her

greatest delight was to mount the table, sideboard, or bureau, look

around till she discovered something reliable (to coin a new word), then

to stand up on her hind legs in a very pretty attitude and with gentle

pats, first with one paw and then with the other, succeed at last in

tumbling the article to the ground. It might arrive there whole, or it

might not, that was just as it happened, and did not concern Miss Pussy

in the least. Then commenced a game, which you might aptly call “Cat’s

Croquet.” If there were more than one ball so much more interesting was

the game. Her very highest felicity was attained when the balls would

unwind. Oh ! what rapture and wild delight she felt then. Oh! the

intricacies of the maze with which she would proceed to surround every

available leg of table and chair, in and out like a weaver’s shuttle,

back and forth, round and round, from one room to another till the ball

was exhausted. Not so Miss Puss, however. She knew not the meaning of

the word. She was ever on the alert, ready and waiting for the next

piece of mischief. When I had enjoyed the possession of this lovely

creature for about a month, my brother’s wife, Mattie, who had been

spending the summer in Muskoka, and was now returning to the city,

presented herself at my house one morning with a large handsome cat in

her arms, almost the model of mine, only bigger ; might have been her

maternal aunt, but proved on enquiry to be only an elder sister. She

also had been a gift from Winnie, for my sister was an adept at

dispensing of her superfluous cats amongst her friends and relations.

“Oh. Nan,” commenced my sister-in-law, “I want you to do me a favor.

Will you keep this cat for me till I come up again in the spring; we are

all so fond of her; Joe would not part with her for anything; we have

all made such a pet of her. Will you keep her for me?”

Now, I hated saying no, for this same sister-in-law had done me many a

kindness during the past summer. Still more did I hate saying yes, for I

had a faint idea (faint, indeed, as it proved) of what I might have to

endure when my present misery was doubled. Still I felt there was no

choice left me, so submitted meekly to my fate.

I was not quite so meek, however, when a few weeks later Bet arrived

with her old “Tom.” She also was going to Toronto, and proceeded to say,

while fondling the monster, of whom she was extremely proud, “My dear

Nan, you promised to have my dog while I was away; will you have poor

old Tom, too!”

“No, I wont!” I burst forth, interrupting her in my wrath. “Take him to

Winnie.”

“But she doesn’t want him,” continued Bet, “she’s afraid he might

scratch the baby.”

“Nothing of the kind,” I said “I’ll go over and see her myself.”

“Well, perhaps, you can persuade her,” said Bet, and I started oft' to

try.

“Now. Winnie,” 1 began, as soon as I reached her house, “it's no use you

saying you can’t have Bet’s cat, you’ve just got to have it. Here I’m

bothered to death, as you very well know, with the two I have already.

I’m willing to have her dog, but I'll be bothered if I take another cat,

so just make up your mind to that.”

After considerable badgering Winnie reluctantly gave way, and said she

would keep the cat; but I don’t know “how the dickens it is,” but old

Tom absolutely refuses to stay over there; he seems to have got it into

his stupid old head that here he will stay, and nowhere else, till his

mistress returns. (Oh, may it be soon!)

Winnie says she does her best to induce him to stay at their place, and

blames it all to my two cats being of the feminine gender; but I will

own I have my suspicions she docs not lay out any special inducements to

keep him at home.

To return to my two cats, or rather my cat and Mattie s. They had soon

made friends, and my cat grew so rapidly after the other one’s advent

that before very long I scarcely knew them apart. This made it very

awkward, and 1 am afraid one often got punished for the other by

mistake. But how could I tell? If they were both in the dining-room, and

one jumped off the table as I entered the room, which of the two had

been at the meat? Sometimes, to make sure, I gave them both a whack, but

this was obviously unjust. Then, again, unless I fed the two together I

felt sure one of them often got two dinners and the other none. -

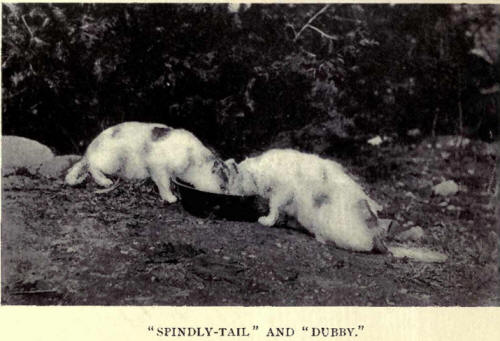

My nephew, Tom the torment, unfortunately heard me mention to a friend

this difficulty I had in distinguishing the cats, and the next day,

while I was busy in the kitchen, he caught my cat and, taking her off

into a quiet corner, proceeded to shave the ha,-r off her tail for the

distance of about two inches from the tip, leaving a long sharp spike

emerging from a ruff of fur. Then the impudent rascal brought her and

dumped her down in the kitchen, saying, “There, Aunt Nan, I think you’ll

be able to tell those two cats apart now, even without your specs; this

one you can call “Spindly-tail,” and the other one "Dubby.” “Oh! you

rogue!” I began, but he was off like a streak before I could say any

more.

Now I will give you a short account of one night and the adventures

thereof, with all its catastrophes. Remember, this is only one night out

of about a hundred and fifty nights which 1 have put in this winter, and

then you can imagine a little of what I have endured. I must explain to

you, before I begin my story, that in this house I have no doors on

other parlor, dining-room or hall, only curtains hanging over the

doorways; therefore, I cannot fasten the cats downstairs. And these same

curtains form the most admirable playground for the nightly game of

hide-and-seek which commences immediately my head is laid on the pillow.

“But why don’t you turn the cats out of doors before you go to bed?” say

some of my hard-hearted male relatives.

“Well, it is twenty degrees below zero. How would you like to be turned

out for the night yourself?”

I can’t shut them up with the hens in the henhouse, nor the ducks in the

duck-house, nor the cow in the cow-house. There is only the ice-house

left, and that would scarcely do on such a night as this.

I glance at them before

I go upstairs to bed. There they lie, stretched out close to the stove,

apparently in the deepest of slumbers; you would think, to look at them,

that an earthquake would scarce disturb them before morning. But

appearances are deceptive, as we all know. Surely, I think to myself,

gazing at them, they will be quiet to-night; and taking my nice hot

brick out of the oven for my feet I steal gently away to my chilly

bedroom in the upper storey. Scarcely daring to breathe for fear of

awaking them, 1 quickly undress in the cold and get, shivering, into

bed. I am just beginning to get a little bit warm when I hear sounds of

stealthy feet coming up the stair-case, pit-pat, pit-pat. Then all at

once a loud whop, a bound and a scuffle. They have begun their game. I

pop my head from under the bed-clothes at the risk of getting my nose

frozen, and call “Scat! scat!” at the top of my voice There is a dead

silence at once; I retreat under the bedclothes and shut my eyes again.

Bang goes something off my dressing table, the bottle of vaseline, like

enough I can hear it rolling. Now they are both there—“Spindly-tail” and

“Dubby.” They have rolled the bottle under the bed—rattle, rattle over

the hardwood floor, a regular bowling match. Again I emerge, bang the

edge of the bedstead, scream “scat” louder than ever, and at last seize

the chair by the side of the bed and pound the floor with it. This seems

to have the desired effect. I fancy I hear them retreating, so once more

get under cover. I am beginning to feel warm again when I hear a faint

purring; it comes nearer and nearer, “He-brew, she-brew” louder and

louder, then I feel a dead, heavyweight on my lower limbs, followed by a

soft prodding all over my body as if I were dough and two or three

bakers were kneading me. At last I can stand it no longer. I spring up

in a rage, and striking off in the darkness send one of them on to the

floor like a cannon-ball, the sparks flying in every direction. I feel

round for the other to do likewise, but she has effected a rapid escape.

Once more I try to sleep. Hark ! what is that ? A blood-curdling sound

from the verandah just like a woman being murdered and a dozen children

spanked at the same time—Bet’s old Tom has arrived. In sheer desperation

I jump out of bed and call the dog—Bet’s dog, Nailer. He gets his name

from a habit he has of sidling up to strangers and fawning on them ;

then when they are tempted to pat him he suddenly nails them. It isn't a

pleasant habit, but. to-night I am only anxious that he should succeed

in nailing that cat, so I open the outer door. The cold rushes in—Nailer

rushes out. There is a sharp skirmish; a great deal of scuffling and

spitting, barking and swearing, and Nailer returns triumphant. “Good

dog!” I say, “you have routed the enemy”; and I hasten to get my half

frozen limbs under cover and compose myself to slumber.

So the night passes away; morning dawns at last. Don’t, I pray you,

think this story any exaggeration; it is the reverse. The repetitions,

the variations are innumerable, but I will have mercy on you, and end my

tale, just remarking, ere I close, that if any of my readers feel they

would like a “nice cat,” with the greatest pleasure in the world I will

give them their choice between “Spindly-tail” and “Dubby.”

P.S.—One month later. Hurrah! I have disposed of “Spindly-tail.” A

certain young clergyman, who was belated here on a stormy night, took a

violent fancy to her. He nursed her all the evening, and took her to bed

with him when he retired. Tremblingly next morning I ventured to offer

him the lovely creature as a present. He jumped to the bait; and after a

loving farewell I have carefully packed her in a basket, and she has

gone far away, thanks be praised! |