|

“What mutter how the

night behaved?

What matter how the north wind raved?

Blow high, blow low, not all its snow

Could quench our hearth-fire s ruddy glow.

...................

Shut in from all the world without.

We sat the clean-winged health about,

Content to let the north wind roar

In baffled rage at pane and door,

While the red logs before us beat

The frost line back with tropic heat.”

— Whittier.

I MUST fulfil my

promise of telling you something of our Muskoka winters, and I just

fancy I hear you saying, with a shudder. “Augh! it must be horrible,

‘winter in Muskoka,’ and this particular winter (1903-04) above all

others. Surely the cities have been bad enough, what with ‘ frozen water

pipes,’ ‘slippery sidewalks,’ and ‘draughty street-cars,’ but Muskoka!!

why, we heard you had more than thirteen feet of a snowfall there.” And

you shiver again at the very thought as you plant your feet on the

fender in front of your blazing coal fire and resume your reading. But

don’t you know, my friend, that in this world there is a law of

compensation, and that though we dwellers in Muskoka may be deprived of

many comforts you enjoy in the city, I want to point out some things you

miss by never seeing Muskoka in her garb of snowy white-Oh, the

loveliness of some of these wintry days, the matchless purity of the

snow, like the finest icing, with which no confectioner’s art could vie.

The trees, every twig outlined with frosty diamonds, sparkling in the

sunshine, and standing out in bold relief against the blue sky. The

effect is absolutely dazzling, and one has to «hadc the eyes with the

hand before the glittering splendor of the scene. Then, the moonlight

nights, the merry young skaters, the toboggan slides, the sleigh-rides,

and, in the evenings, the roaring wood fires, the snug cosy corners, the

happy family gatherings round the hearth, the day’s work done, and all

prepared for enjoyment. “Ah!” but you say, still incredulous, “that is

the bright side; show us the other.” Well, what if we do have to go to

the lake to fetch every pail of water, tumbling down the steep banks

through the snow, searching for the water-hole in the ice, only to find

it frozen over solid, and, after repeated efforts to break it, first

banging the handle off the dipper, and then hammering with the water

pail, all to no effect, have to reluctantly scramble up the bank again

to get the axe ? What if we do have to take our walks abroad in a narrow

rut, one following behind another like a dock of geese, crossing our

feet gingerly, knowing that to step an inch to the side means a sudden

plunge into the beautiful ? We can laugh at these things, because we

have the health and spirits which our brave fight with the snow and wind

imparts. “Dull in winter,” say you? I trow not, my city friend. We know

not the meaning of the word. Work is too plentiful for dulness to show

its nose in Muskoka. We have no time to be dull, and go to bed at night

tired out, sleep like tops, with the blankets well pulled up over our

ears and a small earthquake would hardly wake us.

The Muskoka settlers

seem to reckon the length of the winter from the time the boats cease

running on the lakes until they commence again in the spring. Thus, the

length varies, as in 1902-03 the last boat ran on December 6th, and the

first one came up on April 6th, making that year a winter of only four

months, while last winter, 1903-04 (a record breaker in severity), the

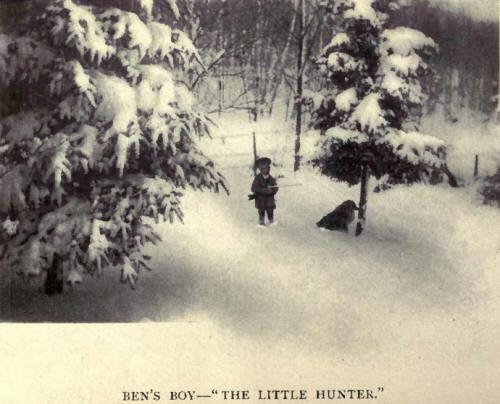

lakes were frozen up fully five months. The hunting season is from 1st

to 15th November, and after the hunters have departed we may fairly say

winter sets in. We then begin to look forward to Christmas and the

Christmas tree. The children are all excited and busy with

presents—home-made ones, of course, in Muskoka, as wc have no stores to

run to, except it may be one visit to Port Carling to see what Mr Hanna

has new in for the holiday trade.

Useful presents, too, rather than ornamental ones are preferred ; and as

oar olive branches here now number nearly twenty, it is no light task to

provide for them all. Unluckily we cannot give the present to them all

which little Willie thought of giving his mother. I must tell you about

that. It was about two weeks before Christmas, and we were all busily

working, when Willie came to me with a very serious face and said:

“Auntie Nan, I want to make a Christmas box for my mother, all by

myself.” “Bless you, my darling,” I said, “you shall.” Taking him up in

my arms, I continued, “What could you make, Willie, all by yourself,

without anyone helping you?” Willie put his arm around my neck and

considered very thoughtfully for a minute or two; then a rapturous look

came over his face and he cried out: “Oh! I can make her a hole. I can

make her a lot of holes,” and then, in an ecstasy of delight, giving me

a big hug, “and she can mend them!” But I’m afraid our young folks

wouldn’t be satisfied with Willie’s presents. They require something

more substantial, though I expect their poor mothers have received many

such presents from them.

We have an acquisition to our family circle this winter, a cousin from

England, who arrived in Canada last summer, after a “ripping” voyage

across the Atlantic, as he informed us on his arrival. He is very tall

and good-looking, but oh, so English! so unmistakably English! He

belongs to the patrician branch of our family, and is only descended

from the plebeian

Hathaways on the female side of his house. We thought him too tony for

anything the first night he was here. “Gee!” said Tom. “but he’s too

tony for me,” while Willie asked innocently, “Is his name really Tony?”

at which we all laughed; but the remark was so apropos that “Tony” he

became to us, and “Tony” he will remain to the end of the chapter.

Notwithstanding his aristocratic appearance and polished manners- -such

a contrast to our rough-and-ready Muskoka boys—Tony soon became a

general favorite, and we were all delighted when we found he would stay

the winter with us. The boys tried to scare him with stories of what he

would have to go through when the cold weather came, but Tony was not to

be daunted. He soon entered into all the work and the sports with a vim.

He learnt to handle an axe, to milk a cow, to mend a fence, to make a

jumper, to cut and haul ice, to wear moccasins and mitts, to pull his

cap over his ears, and only once got his chin slightly frozen, which was

not had for a “greenhorn” who struck Canada in just such a winter.

Well, we had a fine Christmas and a marvellous Christmas tree, though

the presents were so numerous and bulky that more than half of them had

to be deposited on the floor underneath.

The children’s eyes fairly podded out when they beheld its splendors.

Auntie Sue excelled herself this year; her box from Toronto was cram-jam

with nice things for everybody, and our poor home-made presents blushed

with shame at being in such fine company.

Fancy me, “old Aunt Nan,” with my grey hair, almost white, getting a

lovely pink silk blouse, so pretty I could almost eat it; but as for

wearing it, what will folks say if I do?

Gladys got a doll nearly as big as herself, and Willie a rocking-horse

covered with real hair; and as parcel after parcel was unwrapped and

each one’s pile was getting large, the excitement and fun became

uproarious.

Winnie was presented with a big cardboard box, in which, after removing

innumerable wrappers, was a large bottle of castor oil, labelled, “To be

given to the children next day to prevent any ill effects from

over-eating.” I got a big doctor’s book from Tony, in which was written,

“Old Mother Hathaway, so that she can doctor the district.” Fancy such

an insult to an “old maid.” Oh! we had a fine Christmas, and on New

Year’s Day we all went to Bet’s. Her entertainment, of course, exceeded

everything. The table was a sight to behold. I believe if we had all

stayed a week and eaten steadily we could hardly have cleared it. Then,

after dinner, we had charades, at which Winnie and Ben excel, and we

laughed till the tears ran down our faces over their comical

performances. One of the best charades was the slang phrase now so

common, “Search me,” and they had a custom house scene which was most

ridiculous. We finished up with all kinds of games for the children,

till Willie remarked, with the greatest look of satisfaction, “This is

the place where children "joy themselves.” Thus ended a happy day, the

first, we hope, of a happy year.

The next business on hand, after the Christmas parties were over, was

cutting the ice and filling the ice-houses. This proved to be a hard

task for everybody this year, on account of the great depth of snow. Old

settlers say they scarcely remember such a year for snow, and it

commenced to fall so early, while the ice was thin. And though we tried

to keep a space shovelled off, so that it would freeze thicker, our

labor seemed all in vain, for either there would be another snowstorm or

else a wind storm, and we would see our small clearing on the lake

obliterated in an hour.

It was some weeks before we succeeded in getting the ice, and even then

it was poor in quality, so much snow frozen in with it that we had to

pack a double quantity, as it melts so much more quickly when the warm

weather comes. The men had the same difficulty cutting firewood in the

bush. The snow was so deep that when they felled a tree it sank

completely out of sight, and they had to dig it out of the snow before

they could saw it. All this was a novel experience to our tall English

cousin. The boys used to joke him, and say, “it was a mercy he was so

tall, or they would have lost him completely in the bush.' He himself

told me he sometimes sank up to his armpits in the drifts. All our gates

and fences were covered. We did not see them for months, and were quite

delighted to see the posts begin to peep out in the spring.

I did not have the pleasure of seeing the snow disappear, though, this

year, for about the end of March my sister Sue sent a most pressing

invitation for us to spend Easter with them in Toronto—that is, my

brother Ben, Tony and myself. For my part, I was very unwilling to

undertake the journey in the winter. I had heard such dreadful tales

from Bet and my mother of these winter journeys—the long, cold drive to

Bracebridge, the awful roads, the upsets, etc.—that I had always vowed I

would never attempt it, though Bet mocks at my fears and goes herself

every winter. However, both the boys were so determined I should go,

that I had at last to give a reluctant consent. Ben arranged that we

should drive with a neighbor of ours across the lake, who was sending

his two sons and team of horses to Bracebridge for a load of hay.

We left Hathaway’s Bay the Monday before Easter, about three a.m., to

cross Lake Joseph to this neighbor’s house. We were only able to take a

small valise each, and Ben and Tony packed me, with these, on a small

hand-sleigh, which had been used to draw the blocks of ice, and

proceeded to pull me along at a fine rate, crunching and bumping in the

cold and darkness, and mightily glad was I when I saw the dim light in

the distance, which showed we were approaching our destination.

When we arrived we found them all astir, and I went in to get warmed

while the horses were hitched up. When they called me out I found they

had arranged the valises to form a kind of back for me to lean against,

and I had to sit flat on the rough, loose boards forming the bottom of

the sleigh, which had two sets of runners. My brother and cousin sat at

the back, one of the two young fellows driving and the other running

alongside with a lantern to look out for dangerous spots on the ice. We

drove on Lake Joseph for some distance, and then turned across the land

on a rough track, which had been used for hauling wood, in order to

reach Muskoka Lake, down which we were to travel. The road was so bad,

and the horses went so slowly, though the driver kept calling out to

them, "Hurrah! Hurrah!” (a substitute for our English “gee up” which I

had not heard before), that Ben and Tony, feeling very cold, dismounted

and walked ahead. There was a firm crust on the snow, which was hard

enough in most places to walk upon Not for the horses, though; if one of

them chanced to step off the narrow track down he went.

The horses were perfectly aware of this, too. and jostled and pushed

against each other on the icy ridges, balancing themselves and picking

their way more like cats than horses. While I was watching them with

amazement we met with our first adventure, happily not a very serious

one. Our scout with the lantern, who was examining the ground some fifty

feet ahead, turned back and told his brother, the driver, he would have

to turn off the road, as there was a big hole ahead. This he refused to

do; said it was impossible to turn off-—the horses’ legs would be cut to

pieces with the sharp edges of the crust, and that we must keep right

on, no matter what was ahead.

In a moment we were at the edge of the hole. In plunged the horses,

broke through the ice, and were floundering in the water, the sleigh,

meanwhile, perched on the edge of the steep incline, ready to fall upon

them. This catastrophe the driver pluckily prevented by lashing out

furiously with his whip on the backs of the poor horses, and sending

forth at the same time such a volley of “Hurrahs!” that they made one

tremendous spurt, and jumped up the opposite bank, we and the sleigh at

the same moment plunging forward into the hole they left vacant. The old

boards cracked and crashed. The two upon which I was seated parted

company, letting me partly through in a most uncomfortable fashion. For

a moment I thought my end had come, but only for a moment, for with

another sharp lash and a frightful “Hurrah!” the horses leaped again,

and up the bank went the shattered sleigh, and we with it. The driver,

after turning round and asking if I was 14 hurt, calmly dismounted, and

the two brothers proceeded to pull the sleigh together and patch it up

in the best way they could. Part of it, however, had to be left on the

roadside, and then once more we went forward.

After journeying about a mile we came upon Ben and Tony, sitting on a

log waiting for us and wondering what had happened, for the)' knew

nothing of our mishap. They climbed in behind again, and before long we

saw Muskoka Lake, and very thankful we were to get on to its

comparatively smooth surface.

It seemed so queer to me to be trotting over the water and passing the

summer hotels—“Beaumaiis,” and others—which I had only seen previously

from the deck of the steamboats. When we neared the Bracebridge River we

had to turn aside and take to the roads again, as we had heard the ice

on the river was not safe in many parts, the current was so swift, and a

team had broken through and been drowned while driving on it two or

three days before.

No sooner had we left the lake for the road than our troubles commenced

again. The ridges of ice and snow w ere terrible, and to make matters

worse a howling wind and snowstorm came on. I had a big hood to my

cloak, which I pulled right over my head, and my brother behind

improvised a tent out of a big rug which Tony had brought with him from

England. Under this they both lay, comfortably sheltered, and making

great fun of it all. Once we met another team, and our driver thought we

should have to turn off the road. Out I jumped in double quick time, for

I did not want a repetition of my former experience, but happily the men

found they could arrange it without either team having to turn out, for

there was a small flat space near where the other driver could stand

with his horses while we passed by, so I thankfully scrambled back into

my place. The last few were the worst of all, up and down hills the

whole distance, and we not only got very cold, but dreadfully hungry,

too. I had proposed bringing some lunch with us, but Ben had scoffed at

the idea, saying we should be in Bracebridge soon after nine o’clock,

and then get a good her breakfast at the hotel, instead of which it was

half-past twelve when we drove into the town. We had been eight hours

and a half doing the twenty-seven miles—rather slow travelling for a

cold day. Of course the delay meant we had missed our train, which was

due at eleven, and we could get no farther until two o’clock next

morning, so we had to telegraph to Sue, who would be expecting us in

Toronto that afternoon.

Our driver put us down at the hotel, and the smell of dinner saluted our

nostrils as we entered the door, so we hurried upstairs to take off our

w raps and make ourselves a little more presentable. Goodness ! what a

face I had when I looked in the glass, red, swollen, stiff, I hardly

knew myself. I hated going down to the dining-room, but hunger proved

stronger than vanity, so down I went. When the bill of fare was

presented to my cousin he startled the waitress by saying, “I’ll take

everything; bring everything.” Oh, we did enjoy that dinner! I forgot my

red face, and did my best to rival Tony in appetite. After we were

satisfied I went to my room, covered myself up on the bed and fell fast

asleep till after five o’clock; then I went out to take a look at the

town, for I had never been in Bracebridge before, though I had often

been up the river on the boats. It is a bright, lively place, growing

fast, and has some very good stores. I went into two or three of them,

and then back to the hotel to tea. In the evening Ben and Tony wanted to

visit the skating-rink, so 1 went to spend an hour or two with the

clergyman and his w ife, who were old friends of our family.

We got back to the hotel shortly after eleven, and the waiter promised

to call us in time for the 2.15 train. This meant only about two hours’

sleep, so I did not think it worth while undressing, and it was lucky I

didn’t, for the waiter called my brother and cousin, but forgot me! So I

was waked up by my brother coming to see if I w as ready. We were very

near the station, though, so wre had plenty of time. When we boarded the

train we found it very crowded, hot and stuffy. Ben and Tony walked

through the cars until they found one vacant seat for me by the side of

an elderly gentleman, and then they departed to see if there were any

more seats in the smoking-car, my cousin insisting on leaving me his

famous rug, much against my will, for I did not need it, having my own

warm cloak. After the train had started I noticed how tired and worn the

gentleman beside me looked, and, feeling sorry for him, offered the use

of Tony’s rug as a pillow. After a while, I suppose, we must have gone

to sleep, for my cousin says it was so cold and uncomfortable in the

smoking-car on the hard wooden seats that he thought he would come and

see how I was getting on. He came upon me soundly sleeping, and to his

surprise and indignation, beside me, on his rug—sleeping, too—another

man, actually another man ! He was kind enough not to wake us,

notwithstanding, which showed his self-control, but he was never tired

of telling this story to our friends in Toronto, and I got laughed at

more than enough.

But our journey comes to an end—the Union Station at last— and we were

soon on the street cars off to my sister’s. As we turned the corner, of

her street we saw her on the verandah looking out for us, and I need

hardly say we were given a hearty welcome. |