|

Had an inhabitant of

the planet Mars, supposing Mars to be inhabited, visited that section of

Grey County now known as Sydenham township in the year 1830, and after a

careful survey have formed an ineffaceable impression of its general

appearance and, after returning to Mars had visited us again eighty

years later, there are several striking changes he would have noticed at

once. Time has wrought these changes so gradually that it is almost

impossible for the younger generation to visualize a correct mental

picture of the country as it appeared at that time.

First he would have

noticed the disappearance of the forest in large part and the evidences

of civilization in the shape of barns, houses, outbuildings, fences,

roads and all other public and private improvements that follow the work

of man’s hands. Then, in all probability he would have noticed the

lowering of the lake level, for this has been so pronounced it could

hardly have escaped his attention. Then he would have noticed the

complete disappearance of many of the smaller streams arid the dried up

aspect of the larger ones. Then, if he had stayed long enough in the

first place and had been of an acutely observant nature he would have

noticed that the climate was slightly warmer. The average temperature on

this North American continent always rises about five degrees after the

forest has been cleared, for obvious reasons.

These are the greatest

physical changes that have followed the advent of civilization here as

in all parts of the country lying adjacent to the Great Lakes. They have

not added to the beauty of the region but they were inevitable. We

cannot have the wild beauty of the wilderness and the comforts of

civilization at the same time. One of the oldest settlers on the Lake

Shore Line who came to it in childhood has said it was the newness and

wildness of the country that made the first few years he spent there the

most enjoyable of his life. It was Nature at its best, because

unadorned.

The streams were always

full. There were no spring floods, because the snow melted slowly in the

forest shades, the frost left the ground just as slowly and even in

midsummer the heat of the sun’s rays was lost in the thick foliage that

shaded the ground everywhere. The smaller streams were arched overhead

by spreading branches of the trees on their banks and their courses were

often choked with a mass of tree trunks in all the stages of decay. As

they became completely rotted, they were torn away by the current. There

is a passage in a poem by Bryant, in which the noble red men eloquently

(describes the rivers of the wilderness, before they had shrunken at the

destruction wrought by the inroads of the white man’s civilization.

Before these fields were

shorn and tilled,

Full to the brim our rivers flowed;

The melody of waters filled The fresh and boundless wood;

And torrents dashed and rivulets played,

And fountains spouted in the shade.

All these have passed,

and with them have passed the numerous saw and grist mills, erected by

the early settlers. They served well in the day of small things, but

they have given way to the gigantic electric plants which have dammed

our greatest rivers in the quest of power.

The steadily lowering

water level on the Great Lakes is so alarming that it is engaging the

attention of our most eminent engineers, as well as the United States

and Canadian Governments. Just how much the level of Georgian Bay has

fallen since the general settlement on its shores nobody seems to know

exactly. But it has been considerable. Along the western shore of the

lower peninsula of Michigan where authentic records have been kept, the

level of Lake Michigan has fallen eight feet since 1837. There are

reasons for believing it has fallen as much or more in Owen Sound. The

oldest settlers pointed out high water marks of the fifties and sixties

of last century that seem almost incredible. About the only people who

have benefited by the change are the dredging contractors. It has ruined

the appearance of the foreshore along the waterfront of Sydenham, where-

the lake shallows so gradually in approaching the shore, and from

present indications its old beauty will never be restored. It has

destroyed many small harbors, Lunn’s Landing, Coffin and Johnston

Harbors among them, where the largest fishing boats could once find good

anchorage. First they became marshes, then as the water steadily receded

they took on the appearance of pasture patches. In the olden days it was

impossible for the foot traveler to make his way along the beach without

resorting to wading at many points, or making a detour into the

adjoining swamp. But “the lonely shore” of that time had a beauty all

its own that compensated for all such inconveniences, a beauty we have

lost forever in the steady march of modern progress.

From all accounts that

have been handed down to us, it appears the country lying between Owen

Sound and Cape Rich was practically a vast unbroken bush. There is

mention in some early documents of patches of prairie, but they must

have been exceeding rare. Bush fires must have been also of.the rarest

occurance for many years before the first settlers came, or, if there

were such bush fires, they were insignificant and destroyed little of

the standing timber. They were numerous enough after the pioneers came.

Many of them did

positive good, others a great deal of damage. The swamps were in many

places simply impassable, rendered so by a tangled mass of fallen tree

trunks lying in every direction, evergreens broken off many feet from

the ground, and a general confusion that defies description. Fire was

the settler's most valuable ally in clearing out such places ; otherwise

the labor involved in clearing them would have been unprofitable. But

even in the higher land where the hardwood was found, the underbrush was

thick almost everywhere. There were no open arches of the forest over

which poets have raved. An old record shows that two homesteaders spent

the whole summer of 1845, in underbrushing, just south of Annan, and

this in the midst of heavy hardwood timber. So practically every foot of

the land had to be cleared and the first task that confronted the

pioneer after he had built his little shanty “in the heart of the forest

primeval” seemed an appalling one. Yet under the terms of the land

settlement acts of those days, one third of the homestead that had been

allotted him must be cleared and under crop before he could be granted a

patent for his land by the Crown.

There was a wide

variety of hardwood timber, the maple prevailing in most places. Beech,

birch and ash were found in various states of profusion according to the

locality. The rock elm grew to a considerable height and as it carried

that height so well, and dressed so easily it was in great demand for

barn timber. In the swamps could be found almost every variety of

evergreen that flourishes in these latitudes, spruce, cedar, tamarac,

balsam, to mention a number of them, with a few pine. The hemlock was

found on both high and low lying land. This timber was all rather an

unusual size, in fact the Annan district was noted as having some of the

finest in the County of Waterloo, as it was then known. But the soft elm

easily overtopped them all. It grew to a remarkable size in places and

they were quite numerous also, as many as four or five being found in a

single acre, and of the largest kind. In the winter of 1847-48 one was

cut down about two miles south of Annan, which measured seven feet in

diameter on the stump, and fully eight feet at the ground. Its height

was estimated at about ninety feet. Four expert choppers commenced work

on it one morning just after a winter’s breakfast, and shortly after

high noon it came to earth. Three of the choppers had been at work on it

for half an hour the previous evening. The butt was gnarled and fifteen

feet were cut off, then four rail cuts each twelve feet long, the first

one of which made one hundred and five rails, were saved, the top being

left to rot. Another large elm, about the same size in diameter, but

shorter, was in later years-cut down on a farm about three miles

northwest of Leith. With four choppers at work, it took five hours to

fell. Another tall elm which stood “like a city on an hill which cannot

be hid” about the same distance from Annan as the first one, could be

seen from a point fifty miles distant on Georgian Bay, the late Captain

John MacNab being the authority for the statement. These were the

largest trees ever found in Sydenham.

How old were these

monarchs of the forest ? Nobody knows, or at least there is no record of

anyone attempting to number their years. The age of trees is a subject

on which there will always be more or less conjecture. Some oaks in

England are said to have been standing at the time of the Norman

Conquest. The author read recently an account of a tree chopped down in

central New York State in 1854. About half way from the circumference to

the centre the choppers came upon a gash made by an axe and counted one

hundred and seventeen rings outside of it. The axe had been driven into

the tree in or about 1737, and the tree had, it was estimated, been

growing one hundred years earlier than that. There are good grounds for

believing these elms on the Lake Shore line were fully as old. It takes

a lot of yearly growths to make a diameter of seven feet, even if the

elm is a fast growing tree. It may be accepted that these trees had

passed the sapling stage in the days of Cromwell and of England’s great

Civil War. They had looked down upon two centuries of solitude, yet they

were destroyed in the course of a few hours.

It may be well to step

aside a moment and compare these trees with the largest found in the

world. Such a comparison makes them look like a lot of pygmies. Just how

great the disparity was, may be worth a considerable digression here.

In the year 1850, a

party of hunters were pushing their way through the then unexplored

wilderness of what afterwards became Calaveras County, in California.

One of them who had gotten considerably in advance of his companions,

suddenly broke into a valley, about one hundred and sixty acres in

extent, rather it might be styled an ampitheatre. He was the first man

to see what became famous as the “Big Trees of Calaveras County.” At

least if white men had ever gazed on them before, the record has not

survived. The group were solitary specimens of their race. By actual

count there were about ninety-two of them, and they grew in a small

valley of little more than one hundred and fifty acres, as noted, and

within two hundred and forty miles of San Francisco. Their discovery was

a little more than a year later than the chopping down of the famous elm

in Sydenham; some of them, alas! soon shared a like fate.

Their colossal

proportions and the impressive silence of the surrounding woods created

a feeling of awe among the hunters ; they walked around the huge trunks

and gazed reverently at their magnificant proportions, then returned to

the nearest settlements with stories of what they had just seen. These

stories, however, were laughed at as incredible until they were

confirmed by actual measurement.

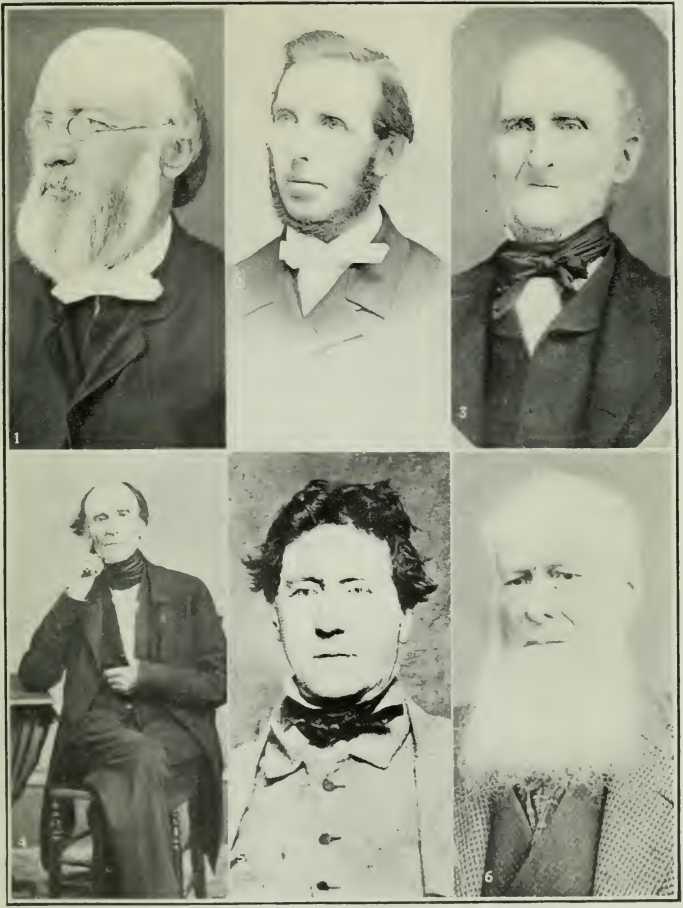

PLATE I.

1. Rev. Robert Dewar. 2. Rev. Alexander Hunter. M. Robert Grierson. 4.

William P. Telford. 5. Thomas Lunn. 6. Thomas Rutherford.

The trees were

immediately named Washingtonians, though some of the savants of San

Francisco endeavered to change this to Wellingtonians, because some

patriotic British botanist availing himself of the discovery hastened to

appropriate the name for the conqueror at Waterloo. The basin or valley

in which they stood was damp, with here and there pools of water, into

which some of the largest trees extended their roots. These gigantic

conifers were of the species known by naturalists as the sequoia. A town

called Murphy was in those days the end of the stage coach lines and

from here to the “Mammoth Tree Hotel”, erected to accomodate the

visitors to the newly discovered world’s wonders, was a distance of only

fifteen miles.

Adjoining the hotel

stood the stump of the “Big Tree”, which was cut down in 1853. It

measured ninety-six feet in circumference, showing a smooth surface and

seventy-five feet solid circumference of timber on the stump, on which

there was ample space for thirty-two dancers, for it was often used for

that purpose. Theatrical performances were also given upon it, the

Chapman Family and Robinson Family, well known entertainers of the time,

giving them there in 1855. This monster was cut down by boring with long

and powerful augurs and sawing the spaces between —an act of vandalism

as ingenious as the Chinese refinement in cruelty in pulling the nails

of criminals with pincers. It required the labor of five men twenty-five

days to effect its fall, the tree standing so nearly perpendicular that

the aid of wedges was invoked to complete the destruction. But even then

the immense mass resisted all efforts to overthrow it,'until in the

blackness of a tempestuous night it began to groan and sway in the storm

like an expiring giant. It succumbed at last to the elements which alone

could complete from above what the human ants had commenced below, and

great was the fall thereof. Its fall was heard at Murphy, fifteen miles

distant and was like an earthquake’s shock. When the great trunk went

down it-buried itself twelve feet in the mire of a creek hard by, with

its two thousand cords of wood. Not far from where it stood were two

giant members of this family known as “The Guardsmen;” the mud splashed

nearly a hundred feet high on their trunks. As it lay on the ground it

measured three hundred and two feet clear of the stump and broken top.

Large trees had been snapped like pipe stems in its fall, and the woods

around were filled with splinters and debris. On its levelled surface

were afterwards built the barroom and bowling alley of the hotel.

One of the most

interesting of the group was called the “Mother of the Forest”. It was

the loftiest of the grove, rising to the height of three hundred and

twenty-seven feet, straight and beautifully proportioned, and in 1860

supposed to be the largest tree in the world. It was ninety .feet in

circumference and into its trunk could be cut an apartment as large as a

common sized parlor and as high as the architect chose to make it,

without endangering the tree or damaging its outward appearance. A

scaffolding was built around this tree, for the purpose of stripping its

bark for exhibition abroad. With damnable industry this was at last

accomplished for a distance of over one hundred feet from the ground,

and it was effected with as much neatness as a troop of jackals display

in cleaning the bones of a dead lion. Such was its vitality however that

it continued annually for about five years to put forth green leaves,

when the blanched and withered limbs showed that nature had done its

best but was exhausted.

The largest of the

whole group paled, however, before a prostrate giant known as the

“Monarch of the Forest.” This monster ha*d long before bowed his head in

the dust, but what magnificence in ruin was his ! He measured one

hundred and twelve feet in circumference at the base and forty-two feet

in circumference at a distance of three hundred feet from the roots,

where it was broken off short in its fall. The upper portion was greatly

decayed, beyond this break, but judging from the average height of the

others, this tree must have towered toward the heavens to at least four

hundred and fifty feet. A chamber, or burned cavity, extended through

the trunk two hundred feet, broad and high enough for a person to ride

through on horseback; a pond deep enough to float a river steamboat

stood in this great excavation during the rainy season. The mind can

scarcely conceive its astonishing dimensions; language fails to give an

adequate idea of it. It was, when standing, a pillar of timber that

overtopped all other trees on the globe. “To simply read of a tree, four

hundred and fifty feet high” observes a contemporary, “we are struck

with large figures, but we hardly appreciate the height without some

comparison. Such a one as this would stretch across a field twenty-seven

rods wide. If standing in the Niagara chasm at Suspension Bridge, it

would tower two hundred feet above the top of the bridge, and would be

ninety feet above the cross of St. Paul’s, and two hundred and thirty

feet above the Monument. If cut up for fuel, it would yield three

thousand cords, or as much as would be yielded by sixty acres of good

wood-land. If sawed into two-inch boards, it would yield about two

million feet, and furnish enough three inch plank for thirty miles of

plank road. This will do for the product of one little seed, less in

size than a grain of wheat.”

Many of our readers

will doubtless smile at the above, and mentally note it (down as a piece

of the grossest American exaggeration. They are mistaken. Out of many

descriptions the author has read of these mammoth trees, all of them

which coincide remarkably as to their size, he has quoted from one which

appeared in Cassell’s Family Magazine for 1860, and a British magazine

of such standing as Cassell’s could be relied upon to give its readers

nothing but the cold facts. It was estimated by scientists who were

authorities on the subject that the prostrate giant known as the

“Monarch of the Forest” had been standing four thousand years ago.

Perhaps it had. It is dangerous to deny such things for there are

stranger things in this world than are dreamed of in our philosophy. As

far as actual bulk was concerned these trees were in all probability the

largest ever seen in the world. But were they the highest? Cheer up,

gentle reader, for the worst is yet to come.

Late in 1884, James

Anthony Froude, the eminent English historian and litterateur, left

London on a trip round the world, going by way of the Cape to Australia

and New Zealand. He has left us a splendid narrative of the journey,

which was made in a leisurely manner and with ample time for

observation, in a volume called “Oceana”. Like many another valuable

volume, it must have had a small sale, as copies of it are rather rare.

While in Australia he visited all the large cities ; Melbourne was then

the largest. While there he heard tales from enthusiastic Melbournians

of a wondrous sight to be seen not far from the city, and, as the city’s

guest of honor, he was pressed to go and see it. He consented.

Conveyances were secured after the journey by rail had ended by the

party that had accompanied him, and after a journey of about ten miles

during which the scenery had grown wilder and wilder, and the trees

steadily taller, at a point near the sources of the River Yarra and

about ninety miles from Melbourne, the distinguished Englishman was

shown trees standing in a valley which he says averaged from three

hundred and fifty to four hundred feet high.

These trees could not

be counted in the course of a few minuU's like those in California. They

were there in regiment.- and brigades, towering up in the shelter of a

mountain like “the tall masts of some great Amiral.” In fact Froude

attributed their great height to their sheltered position and the rich

nature of the soil. The hand of the destroyer had been busy and several

of the largest levelled, but the government of Victoria had intervened,

not altogether effectually however. These trees were of the gum-wood

species, or the far-famed Australian eucalyptus. Considering their

height, their girth was not remarkable ; the visitor spanned the

circumference of one with his arms, but the result by a lapse of memory

is forgotten. It is certain however, they were not nearly so bulky as

the Calaveras County trees. But there were a few among them that ran up

to four hundred and twenty and thirty feet, and Froude was assured that

one had been felled that measured four hundred and sixty feet. There was

no supposition about the height of this one, as in the case of the

long-fallen tree in California; it had actually been measured, and, as

far as is known, it had been the highest tree in the world. It was but

natural that a man of Froude’s mentality should have been profoundly

impressed by such a sight. There are some poor unfortunates among us

who, like the author, have never seen the Woolworth building, but as

between seeing it and one of these mighty gum-trees, our choice would at

once fall to the latter. How long had their towering tops waved in the

gales of the passing centuries and “held their dark communion with the

cloud ?” Froude does not even venture to guess, but as geologists assure

us that Australia’s surface is probably the oldest land on the face of

the globe, forming as it did part of a long-lost Antartic continent,

their birth may have reached back into the remotest ages of antiquity.

Ancient empires had risen, flourished and decayed, civilizations had

waxed and waned while they were adding cubits to their statue. At last,

after Tasman, came the adventurous Captain Cook, and after him came the

white man with his genius for destruction. It was nothing short of a

crime against man’s better nature that even one of such trees should

have been destroyed. They must have “The Hand that made us is divine.”

So if we were to take

one of these huge elms in Sydenham, and piled on top of it in their

natural position three others of like size, the height of the topmost

one would still have fallen below the crests of some of the sequoias of

California or the gum-trees of Australia. Had they been standing

alongside them, they would have looked like saplings. Sir Walter Scott

once saw a vessel unloading squared timber from America, at Leith; he

gazed long and earnestly at the sight and remarked to a companion that

it must be a great privilege to live in a country where timber grew to

such dimensions. What he would have said had he seen the Californian

trees standing on their native heath we can only surmise, but his

incomparable genius in poetic description would doubtless have risen to

the event.

But the trees in

Sydenham were large enough and numerous enough in all conscience, for

the men who were clearing the land, a process that will be described at

length in a later chapter. In a very literal sense one could not see the

forest for the trees. In their wild fastnesses, more particularly on a

cloudy day, it was the easiest matter in the world to become hopelessly

lost. This was the unfortunate predicament in which two young fellows,

James Ross and Henry Taylor, the latter eleven years old, found

themselves while hunting cattle one afternoon, as late as May, 1846.

They spent the night in the woods and the alarm of their relatives is

easily imagined. The blowing of horns and ringing of cowbells echoed

along the Lake Shore, yet these lads were within from two to three miles

of their homes. Trails to the various shanties from the roads were

marked by blazes on the trees and had to be carefully followed. The

trackless wilderness of the North American forests has never before or

since been so accurately and vividly described as it was by Fenimore

Cooper in his Leather-stocking i Tales. In this respect, however, he has

no inconsiderable rival in Francis Parkman, the historian of Canada

under the French, and our readers are urged to consult both if they wish

to form any adequate picture of the wilds of North Sydenham, as they met

the eye before the coming of the first pioneers.

Into this unbroken

wilderness came the vanguard of the stream of settlers, along about

1840, like a band of destroying angels. After erecting their first rude

shanties, the newcomers turned upon the trees as they would have upon

natural enemies. The forest had to be cleared and converted into farms

if they wished to live long upon the land. The process would have been

viewed with the most mournful feelings by the lumbermen of this day and

age, had they been able to witness it. One by one these upstanding

giants and their smaller brethren down to the tiniest sapling

disappeared, as acre after acre was cleared. They were cut into

convenient log lengths, piled up in huge heaps and, after a season, the

fire brand was applied. It seems like criminal waste to us now that the

finest hardwood timber, often three and four feet in diameter, should

meet such a fate. But had we been in their position would we have done

differently? The pity is that it had to be. These men could not foresee

the days of coal strikes and fuel famines. They never dreamed that maple

flooring would one day sell at one hundred and ten dollars a thousand.

Probably they knew nothing of the economist’s theory of the value of

utility and even if they had it would not have made an iota’s difference

to them. IIa»d they been men of wealth and leisure, they might have

looked into the future and seen the day when such standing timber would

be worth countless wealth, but men of wealth and leisure do not move

into the backwoods. So the indiscriminate slaughter went on. On some

farms ten acres were cleared in a single season, altho such cases were

rare. It was sinful waste to clear some of the land, even in that day

and time, because it has been fit for nothing since. Afforestation has

as yet never been seriously attempted in Sydenham, but the time is

coming when men will be found disinterested enough to replant to trees,

some at least of the land that never should have been cleared, and leave

it to their children to reap where they have sown.

Probably there were men

among the pioneers who felt some stirrings of contrition when they saw

these splendid trees, many of them their Creator’s finest masterpieces

in their class, go crashing to earth. Cut the same devastation was

proceeding wherever the pioneer found a foothold, and in some places

with far less justification. In that “far-flung” (to adopt a

Kiplingesque word that has been worked to death) outpost of empire, New

Zealand, the destroyer has been at work in the vast forests that cover

portions of the North Island. The insatiate greed of commercialism and

the destruction its wanton vandalism has wrought in these same forests,

possibly as fine as will be found anywhere, has stirred the indignation

of an Auckland poet.

Gone are the forest

tracks, where oft we rode,

Under the silver fern-fronds, climbing slow,

In cool, green tunnels, though fierce noontide glowed

And glittered on the treetops far below.

There, ’mid the

stillness of the mountain road,

We just could hear the valley river flow,

Whose voice through many a windless summer day

Haunted the silent woods now passed away.

......Aye, but scan

The ruined beauty, wasted in a night,

The blackened wonder God alone could plan,

And builds not twice! A bitter price to pay

Is this for progress—beauty swept away.

Another matter should

be touched upon briefly before closing this chapter. There is a popular

impression that in the earliest years of settlement, the woods fairly

swarmed with game and Lake Manitou, the euphonious name given to the

noble sheet of water by the redman, and now known under the rather

insipid one of Georgian Bay, just as freely swarmed with salmon trout.

This is hardly correct.

Game was much more

plentiful then than now, of course. But the fur bearing animals of the

forest, it should always be remembered, followed the law of the survival

of the most fit. They preyed upon one another and thus kept down the

natural increase. No doubt there were unusually hard winters, when many

of them must have died of actual starvation. For many years after the

first settlers came the game seemed to run in cycles, like the seasons.

Thus there is mention in some early memoirs of how the black squirrels

were on two occasions so numerous as to be a nuisance. They were much

prized for making pies. A Leith resident killed four with a rifle, in

walking from the dock to the village. Again, there were years when the

red squirrel came in myriads. There is mention of one hundred and thirty

being killed in one day with stones. Like King David, the man who

wrought such execution must have been a great shot with a pebble. On

another occasion, a party coming from Owen Sound by boat, passed through

an immense swarm of red squirrels, at Squaw Point, swimming from the

west to the east shore of the bay. There were a few deer and an

occasional bear, but they were soon driven out as settlement progressed.

The partridge was plentiful at first, and was almost a daily item in the

bill of fare in many a shanty. It was roasted before an open fire on a

spit that revolved slowly, being basted meanwhile. The first settlers

used in after years to tell stories of the flights of the wild, or blue

pigeon, that stagger the imagination, but as all these stories agreed

they must have been true. They darkened the face of the sun and broke

down the limbs of trees when they alighted for the night. It is now, to

all intents and purposes, as extinct as the dodo.

The same story applies

to the fisherman’s sport, in fishing from the steams or on the bay

alike. Every stream seems to have been a trout stream, wherever the

trout came from. They were certainly not stocked. But the trout was a

much sought after delicacy and in the first twenty-five years it was

largely fished out, altho good catches were made at later dates. The

gradual drying up of the smaller streams in many cases completed what

the angler had begun. In some cases, such as at Shepherd’s Lake, other

fish like the perch were stocked and they played havoc with the trout.

As to the shoal fishing on the bay, the earliest accounts are rather

confusing and contradictory. For one thing the trolling tackle used was

of the crudest description and would be laughed at now. Some large hauls

were undoubtedly made and the trouble must have been to find a market

for the salmon trout, the fish found by far the most frequently on the

shoals. The writer remembers a conversation he had with a member of the

Desjardine family, famous fishermen of the earliest times, in 1896. He

said that one of his uncles had set a gang of nets at Johnston’s Harbor

one night late -j in the fall, just twenty-five years previously, which

would ' be about 1871, and that he lifted next morning for not a single

fish. It is our own conclusion that there was as good fishing around

Vail’s Point thirty-five years ago as at any previous time. This is a

peridd that comes within our own recollection. In the fall of 1887, we

saw any quantity of salmon trout, large and small, thrown on the fishing

tugs at eight and nine cents each. The shoals swarmed with them. On one

point, however, all the earlier accounts agree. The average size of the

salmon trout was much larger then than now.

The largest single

catch of which the author knows and of which there is authentic record,

was made by the late John Gibson of Leith, with two or three companions,

in a heavy yawl which was familiarly known on the shoals from Vail’s

Point westward, forty and fifty years ago. This catch was made along

about 1884 or 1885. Mr. Gibson and his crew were enjoying fair fishing

when the wind and the sea began gradually rising, and, as was quite

usual in such a change of weather, the fish kept biting better and

better. They saw at last a chance of making the century mark and

resolved to play the game until driven ashore by the weather. When they

reached the boathouse that night, after a stiff battle with the

elements, one hundred and one fish were thrown ashore. Without doubt

there were larger catches than this one made, at one time or another,

but there is positive and authenticated record of it, whereas many of

the large catches boasted of are the figments of a feverish imagination.

Such was Sydenham

eighty-four years ago. The picture is imperfect, of course, but it will

give the reader some idea of the task that awaited those who invaded

this unbroken wilderness, in the hope of making homes for themselves. |