|

AT a meeting of the people on March 4th, 1824, called to

consider the purchasing of land for a burying-ground and on which to

build a house of worship, Malcolm McNaughton was made Chairman, and

James McLaren, Clerk. It was decided, if possible, to buy the south half

of the west end of Lot 7 in the 4th Concession, but if it could not be

obtained to purchase one or more acres near the centre of the

Settlement. Malcolm McNaughton, Duncan Campbell and James McLaren were

appointed a committee to make the purchase. They were unable for some

reason to buy the south half of the west end of Lot 7, which seems now

more unfortunate than it could have appeared then, because it would have

afforded a fine location for a Church-building and room for a large

cemetery. The committee purchased one and a half acres of land from

Andrew Laidlaw, the same being the north-west corner of Lot 6, and

obligated themselves to pay in good mercantile wheat at cash price £7.

3s. 3d, lawful currency, the wheat to be delivered at Andrew Laidlaw’s

house, or at Jasper Martin’s mill at Trafalgar by February 1, 1825. At ,

another meeting on April 9, 1824, at which Alexander Bowman was

chairman', and James McLaren Clerk, Malcolm McNaughton, James McLaren,

Duncan Campbell, Andrew Hardy, and Jasper Martin were elected trustees

for one year, and it was decided to proceed with the erection of a

meeting-house during the ensuing summer, and also a schoolhouse, and to

lay out the burying ground into lots. John McTavish, Robert Shortreed

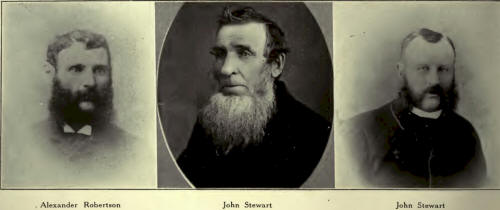

and Alexander Robertson were chosen School Trustees. These pioneers,

like their forefathers in Scotland, believed that Kirk and School went

together. Where this Schoolhouse was to be built is not mentioned, but

there were two school-houses in the early days in the Block about whose

location there can be no question. One of these schools was situated at

the jog in the sideroad running west from Manse-wood station on the farm

of Alexander Robertson, who owned two hundred acres, the same being Lot

5 in the Second Concession. After some years a frame building further

west in the Concession was erected on Lot 6 on the 1st Concession Line,

and north-east corner. It is said that this school was called “Ligny” by

Robert Little when he taught there. Some years ago the school was moved

back to near the original location. The other Schoolhouse, which was

also a log building with an open fireplace, was situated on Lot 13 in

the. 4th Concession West, nearly opposite the lane leading into the farm

of John Stewart Sr., and now the property of Stephen Hagyard. The first

mentioned school was taught by Alexander Robertson, commonly spoken of

as “Squire Robertson.” He was a cousin of Alexander Robertson, Sr., who

lived on Lot 8 in the 2nd Concession, the father of Alexander Robertson

on whose farm the schoolhouse was built. The other school was taught by

William Glass Stewart. The boys and girls who went to these schools were

on the lookout for wild beasts. One morning as the two youngest

daughters of Alexander Robertson Sr., were on their way to the school

taught by Air. Stewart, they saw a big black bear in the woods right

before them. As the bear showed no disposition to withdraw, and they did

not wish to meet him, they speedily made a “strategic retirement”

homewards, and thereby lost a day of Mr. Stewart’s valuable instruction.

It may seem strange, but it is true that if the bear had captured the

younger of these girls, and carried her off, this chapter woul$ never

have been written, and many other events of an interesting character

would never have taken place.

The first school teachers who came from the Old

Country,^were generally well educated, and able, to teach Latin to any

of their pupils who required it. This was true of both Mr. Robertson and

Mr. Stewart. At least two boys, John McKinnon and Angus Me Coll,

received their start in Latin from ^r. Stewart, and read Cornelius

Nepos. These, two, when young men, together with Robert Wallace of

Chinguacousy, and Thomas Wardrope of Flam-borough, it is said, rode in a

lumber wagon to Kingston in 1842, and became members of the first class

of Queens College. Mr. Stewart ^afterwards taught in the Quatre Bras

School, and con: tinned teaching in other schools to a good age. He died

in Manitoulin Island, where he had gone on a visit. The first teachers

were all men, and they held undisputed sway for about forty-five years

in the schools of Esquesing. Then began the gentler reign of the young

women teachers, which the boys liked better, but whether the change was

the best thing for all the boys this historian saith not.

Although not one of the first teachers in the Block we

mention here Robert Little, who won greatest fame probably as a teacher.

He was a Scotch Presbyterian, a good scholar and a strict

disciplinarian. He had taught school in Scotland and England. In 1852 he

began his teaching career in Canada in Waterloo school, where he

remained one year. Among other pedagogic feats in this , school he made

an impression on the hands and memory of the writer, when in his eighth

year, with a leather weapon calld ai taws. The taws was an importation

from Scotland, and Mr. Little was strongly attached to it. He believed

that very valuable results followed from its proper application. In his

judgment, founded upon a wide and varied experience, this instrument

stimulated the mental facultes of a boy by way of his hands, and secured

his great respect and love for school order. Mr. Little went next to

Ligny school for nine years, and then to Acton for nine and one-half

years. By his knowledge and methods as a teacher, and the frequent use

of his cultural assistant, the taws, he helped a number of lads on their

way to become teachers, lawyers, preachers and physicians. He became

inspector of schools for Halton in 1871, and senior inspector of schools

of the Parry Sound and Algoma districts in 1875. George W. Ross, when

Minister of Education in the Mowatt Government, had Air. Little prepare

first and second readers for public schools. He died in Acton on April

8,. 1885, and was survived by Airs. Little, who now lives in Los

Angeles, Cal.

In the Waterloo, Ligny and Quatre Bras schools the Bible

was for years a regular text book, and for some time the Shorter

Catechism was recited.

One of the first teachers in Milton was Thomas Aitken,

and he taught there a Sunday Bible Class for young men. He died while

still a young man. He was a brother of Thomas Aitken and Matilda, wife

of Alexander Robertson on Lot 5 in the 2nd Concession. They were first

cousins of Thomas Carlyle.

The library, kept in an addition to the Quatre Bras

schoolhouse, exerted a great influence during the years in which it

flourished. It is said that there was not a better selection of books

outside of the cities. It had some of the latest and best books in

history, biography, travel, theology, astronomy, geology, fiction etc.,

and the poets.

That some of the solid books of information in this

library found readers in the Scotch Block would in these days, probably,

be a matter of surprise to many people. The annual meeting of the

Association was held in the evening, and the schoolhouse was crowded.

Every member was entitled to propose a book, but a majority vote was

necessary to a purchase. Many good books were contributed. When the

Mechanics Institute in Milton was opened it was decided to close the

library and divide the books among the members. A regular patron of the

Library coming on one occasion to get a book was told by the Librarian

of a certain work, and asked if he would not like to read it. He

answered; “Na, it’s nae soun.” These men, for the most part, had decided

opinions as to what constituted good books, and good preaching. They

were very positive also in their political convictions, but sometimes

likely to be prejudiced through partizan feeling. It was one’s own party

always in a general election that could save the country from ruin,

while the candidates of the opposing party were blind guides, who should

never be entrusted with the reins of government.

They were at the same time very conscientious. As an

illustration of this they generally believed that they should "Remember

the Sabbath day to keep it holy,” but with the best of them it

occasionally cost an effort to do so. One of them returning home from

Church on that day surprised his brother reading a newspaper recently

received from Scotland, and while saying nothing his look was full of

pain and reproof. The erring brother folded up the paper at once, but

feeling that it was up to him to attempt an excuse said: “hoots, mon, I

was just reading over the deaths.”

At the Annual Meeting of the congregation in 1825 Andrew

Laidlaw, Thomas Shortreed, Jasper Martin, Alexander Bowman and George

Darling were elected Church trustees. Andrew Laidlaw was made Clerk, and

Robert Shortreed, Treasurer. The trustees were given power to procure

estimates for building a meetinghouse of a certain size and plan, and to

let the contract. Each subscriber was required to pay into the treasury

one-half dollar, and give five days work, or more if necessary, and

failing to perform the labor to pay three shillings and three pence per

day. The trustees agreed with William Carhart to frame and cover the

building by the last of June, to pay him thirty-five dollars, when the

frame was raised, and thirty-five dollars in good mercantile wheat at

Jasper Martin’s mill by October 1st 1825. In those days wheat was more

easy to raise than money. When the frame was put up many men were

present, but only one of them wore a pair of shoes. It was common to

wear shoes when men went to Church, but to work, in summer, in the bare

feet, both in Canada and in New York State. At a meeting on July 22,

1.925, it was decided that each subscriber to the building should pay

one and one-half bushels of wheat in September, or six shillings and

three pence, to enclose the building, put in doors and windows in the

lower storey, and that those behind in labor should cut, and draw logs

to the saw-mills with the first sleighing, and forward the lumber as

soon as possible.

At the Annual Meeting in April, 1826, John Sproat, David

Knight, David Darling, William Campbell and David Scott were elected

trustees. It was decided to lay the floors of both stories, to lathe and

plaster the house and put in windows, the carpenter work to be done by

the last of September, and the ceiling by the end of October. Each

subscriber was to pay one dollar by August 1st, and the remainder by

January 4th, 1027, and the labor this year was to be four days for each

subscriber, and more if necessary. At the meeting on April 1, 1827,

Alexaxnder Robertson, Walter Laidlaw, James Campbell, James McLean and

Adam Sproat were elected Trustees, Alexander Robertson, Clerk and Robert

Shortreed, Treasurer. In September, 1827, James McLean was paid £15. 2s.

3d., for carpenter work, it being certified that he had done his work in

a mechanic like manner. In April, 1831, Mr. McLean was paid in full. In

April, 1829, it was decided that all wheat payments in arrears, and all

new payments, should thereafter be paid in money. Wheat was no longer a

medium of exchange in Church transactions.

Details as to names, dates, and business dealings have

been given so far, because they! throw light upon conditions existing

when the meeting-house was being built. Although in use, it was not

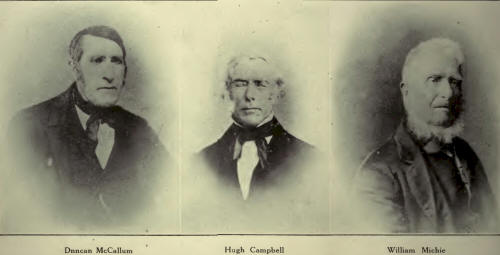

completely finished until 1835, when Duncan McCallum was paid £35, 5s.

for the carpenter work done by him. The people had the necessaries of

life, but money was scarce. The building progressed by stages. It was a

long pull, but done at last to the great satisfaction and joy of the

people, and those who can remember the interior of the Church still

think it was not bad to look at, and very comfortable. The pine of the

inside finish, if memory is correct, was without a knot, and the

workmanship of the best. The exterior was somewhat barn-like, and there

was no paint without or within.

The Church stood endwise to the public road, as does the

present building, which is on the same site. There was a door at each

end, and as one entered there was a stair leading to the gallery, which

extended around three sides of the audience room, and on the south side,

high enough to command a fair view of the gallery, the panelled pulpit

with a sounding-board overhead was placed. The minister reached it by a

longer stair than is seen in the modern Church, and when he gained the

summit he opened a door with a brass knob, and let himself in, and

sitting down on a seat with a red cushion left only the top of his head

visible from the floor. Below the pulpit, and in front of it, was the

box, or desk, of the precentor, who also had to open a door to get into

it. The pews of the Church had doors also, but just why these old

Churches had so many doors the readers of this history will have to

guess. In the worship of the Church the people stood up in prayer, and

remained seated while they sang. They sang the Psalms to the same tunes

they did in Scotland.

“Those strains that once did sweet in Zion glide,

He wales a portion with judicious care;

And ‘Let us worship God;’ he says with solemn air.”

They chant their artless notes in simple guise;

They tune their hearts, by far the noblest aim;

Perhaps “Dundee’s” wild warbling measures rise,

Or plaintive “Martyrs,” worthy of the name,

Or noble “Elgin” beats the heavenward flame.

The sweetest far of Scotia’s holy lays;

Compared with these Italian trills are tame;

The tickled ears no heartfelt raptures raise;

Nae unison hae they with our Creator’s praise.”

—Burns.

Walter Laidlaw occupied the precentor’s desk for many

years. He generally took notes of the sermon, and his face was an index

of his valuation of its worth. At a Gaelic service Duncan McCallum led

the singing.

The table on sacramental occasions extended along the

aisle running from the front door to the opposite door at the rear, and

in the boyhood days of the writer was occupied at least twice. The

services in connection with the observance of the Lord’s Supper were

held on four days: Friday, Saturday, the Sabbath and Monday. Friday was

the fast day, and Monday was a thanksgiving day. On Friday, or Saturday,

the tokens, which were small pieces of metal, were handed out to

intending communicants. The great day of solemnity was the Sabbath, and

the house was filled to its capacity.

For years begininng with April 29, 1839, as the

worshipper entered the Church he was confronted by a plate, which

appeared to be of pewter, inviting him to place an offering thereon

before he passed on to his pew. This method was followed by boxes with

long handles passed along the pews.

We have been anticipating. At a congregational meeting

held after the completion of the Church, prices were assessed on

sittings. The person taking the highest number of sittings in a pew was

entitled to the pew. All who wished to retain their pews from year to

year could do so, but any person not paying his rent ten days after the

expiration of the year, and failing to satisfy the trustees for his

neglect, was to forfeit his pew, or seat. It seems there were slackers

in those days, also, who failed to come across promptly with their money

for Church support, and they were penalized for their tardiness. The

front gallery sittings, as being most eligible, were fixed at ten

shillings, and those behind them for less. Sittings on the ground floor

were fixed at nine shillings.

Those who sat on the back seats of the gallery found they

could sleep as well there as at home. .

The men who had contributed to the payment for the land,

and the building of the meeting house, are in the Church reports spoken

of as “Subscribers,” and as “Proprietors,” and some of them seem to have

assumed that in voting in congregational meetings they had privileges

not belonging to people who came later into the congregation. |