|

“Where the blue hills of

old Toronto shed

Their evening shadows o'er Ontario’s bed.”

Thomas Moore.

TO tell in full the

story of York County would be to re-write much of the history of

Ontario—one might almost say of Canada itself. But my endeavour will be,

while making slight reference to the great historical events, to use the

very limited space at my disposal in picturing to the best of my ability

what one might call the domestic life of the county.

Long before the cession

of Canada to England, what is now York County was known as the Toronto

region, and in the middle of the eighteenth century the French fort,

Rouille, often called Fort Toronto, was erected just east of the Humber

River, with a view to the discomfiture of the enterprising English

traders who had been known to cross the lake from the south to traffic

with the Indians, bringing their rich supplies of furs down the Humber.

The first exploration

of the place under the English Government was made in 1788, when Deputy

Surveyor Collins reported to Lord Dorchester that “as a military post I

do not see any striking features to recommend it." In 1791 surveyors

began to mark out a row of townships along Lake Ontario. Of these York

Township was first named Dublin, and Scarborough Glasgow.

In that year Lord

Dorchester ordered that grants of land of 700 and 1000 acres in extent

should be laid out at Toronto for three French gentlemen, but before the

order was executed “the new Province way duly constituted,” there was a

change in the regulations, and the three got no land near the site of

the capital of Upper Canada, which was started in its career as "a very

English town” by that sturdy Briton, John Graves Simcoe. He baptized it

with the English name of York, and established there as close a copy of

British political institutions as he could contrive. For many years to

come, moreover, it was a common, and the Canadians used to think a

reprehensible, custom to bring in Englishmen to fulfil the executive

functions of government, in due accordance with English precedents and

traditions. At first the development of York depended almost wholly on

its being the seat of government.

In 1797 Chief Justice

Elmsley, who had just arrived from England, objected to the removal of

the courts from Newark to York, on the ground that the latter place “was

forty miles beyond the most remote settlements at the head of the lakes”

(I quote from Mr. Yeigh’s book on Ontario's Parliament Buildings), and

that “the road to it passed through a country belonging to the

Mississaugas. There was no jail or court-house there, no accommodation

for grand or petit juries, none for the suitors, the witnesses, or the

Bar, and very indifferent for the Judges, so that those attending had to

remain in the open air or be crowded in tents. Many of the jurors, too,

would have to travel sixty or eighty miles, and be absent from home not

less than ten days, so that a mere fine would have no effect as against

the expense, loss of time and fatigue in going to that point; in fact,

he very much feared that he would not be able to form a jury at York."

The Chief Justice, however, was forced to give way and resign himself to

holding courts in York.

The first jail was a

squat wooden building, surrounded by a high stockade. It stood a little

east of that now busy spot in Toronto—the intersection of Youge and King

Streets. By the year 1811 the building was dreadfully dilapidated, and

an order was given to repair it. Then it was discovered that there were

no suitable spike-nails to be had of any of the dealers in the town, but

after long delay some were furnished from the military stores. In the

following December the Sheriff reported that “the prisoners in the cells

suffer much from cold and damp, there being no method of communicating

heat from the chimneys, nor any bedsteads to raise the straw from the

floors, which lie nearly, if not altogether, on the ground.” He

suggested that a small stove should be placed “in the lobby of each

range of cells,” and that some rugs and blankets should be supplied.

This was done, and the poor prisoners must have blessed Sheriff Beikie

for his humanity. Debtors as well as criminals were confined in the

jail, and in those days York had its stocks, its pillory and frequent

hangings. But in 1817 a number of men arrested in the town in connection

with the troubles of the Selkirk Settlement on the Red River had to be

taken for safekeeping to Montreal. Seven years later a new jail and a

court-house of a rather pretentious type of architecture in red brick

were erected.

By this time there were

many settlers in the country round. At first communication between the

different settlements was, of course, chiefly by water, but Yonge

Street, leading northwards, and Dundas Street, leading westwards, were

cut through the county at an early date. As now, the pioneers of the new

settlements were of different “nations and languages.” Of the Quaker

immigrants from Pennsylvania (some of whom settled in King and

Whitchurch Townships), something was said in the article on Ontario

County. These settlers, by the way, were considerably annoyed by long

delays in the issue of patents for their lands, but on appealing to the

newly-appointed Governor Hunter, a vigorous soldier, they obtained them

in two days.

In 1794, some years

before the arrival of the Quakers, sixty German families came from the

south side of Lake Ontario and settled in Markham Township. Some of the

Germans travelled, it is said, in wagons with bodies of close-fitting

boards with caulked seams, so that, in case of necessity, “by shifting

the body off the carriage" it served, presumably as a boat, "to

transport the wheels and the family.” In going from York to Holland

Landing the pioneers often used ropes passed around saplings to haul

their wagons up or steady their descent down the steeps of Yonge Street.

At the close of the

eighteenth century grants were made to a number of French military

refugees who had been driven from their own country by the Revolution.

Wishing to take up lands in a block, they were settled in the rather

sterile region known as Oak Ridges, just where the four townships of

King and Whitchurch, Vaughan and Markham, come together, and for a

little while counts, viscounts and "chevaliers" followed more or less

successfully that strenuous mode of life, "roughing it in the bush.”

Occasionally they went down to York to add a special lustre to the balls

given by the Governor or other officials, and it is on record that the

jewels of one aristocratic lady, “Madame la Comtesse de Chalus,” created

a great sensation. A good many years later, York’s first fancy-dress

ball, given “on the last day of 1827, conjointly, by Mr. Galt,

Commissioner of the Canada Company, and Lady Mary Willis, wife of Mr.

Justice Willis,” caused a great stir. But little “Muddy York” seems to

have had no lack of excitements concerning more important matters. There

were the comings and goings of Governors, the sittings of the courts,

the doings of the Legislature, and, above all, the happenings during the

years of warfare, 1812 to 1814. On the outbreak of the strife volunteers

from York were sent promptly to the front, and everyone knows that the

gallant Brock was leading men of this county to the charge at Queenston

Heights when he got his death wound. Indeed, his last words were, “Push

on, brave York Volunteers!"

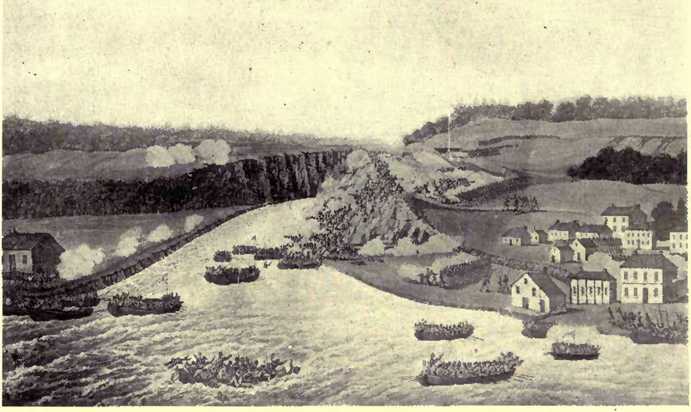

In 1813 the men of York

twice found the war carried into their own home district. On April

27,1600 Americans under Generals Dearborn and Pike swooped down upon the

little town and effected a landing in Humber Bay. They were pressing

eagerly forward to drive out the defenders of the fort, when a magazine

suddenly exploded in the western battery, and a number of men on both

sides were killed and wounded. Amongst the latter was General Pike, who

died on shipboard a few hours later.

Thinking the town

indefensible, Major-General Sheaffe, with his few British regulars,

retreated towards Kingston, and the invaders burned all the public

buildings. It is said that when they were on the point of setting fire

to the Parliament buildings they found above the Speaker’s chair in the

Legislative Chamber what they took to be a human scalp. “This startling

prize, however, turned out to be but a periwig, or official peruke, left

behind by its owner.” Unfortunately all the state papers were burned

with the building.

It was on March 6,

1834, that the town of York became (with extended limits) the city of

Toronto. The first mayor of the municipality (in fact, the first mayor

in Upper Canada) was William Lyon Mackenzie, the popular hero, who had

been five times expelled from the Assembly and had been as persistently

re-elected by the “free and independent electors” of York County.

WINTER SCENE ON TORONTO BAY

Indeed, it is safe to

say that, for a considerable number of-years, this "wiry and peppery

little Scotsman, hearty in his love of public right, still more in his

hatred of public wrongdoers" was the most conspicuous figure in York

County, not excepting even the Governors in their picturesque trappings

of state.

Mackenzie, moreover,

was the occasion of, or the actor in, many lively scenes characteristic

of the early days, and therefore I make no apology for dwelling at some

length on his doings and sufferings, though I cannot pretend even to

mention the names of many men who served their country more wisely and

not less well.

When the little capital

in the wilderness could boast only a population of two or three thousand

souls, political contests were waged with the bitterness and the fierce

personalities -of an ancient hand to-hand fight, and apparently the

onlookers took much the same kind of savage delight it the shrewd blow’s

given and received as their ancestors had found ir. the single combats

of accredited heroes.

This is the portrait of

the redoubtable little champion of the rights of the people and the

freedom of the press, as sketched by a friendly hand: “Mackenzie was of

slight build and scarcely of medium height, being only five feet six

inches in stature. His massive head, high and broad in the frontal

region and well rounded, looked too large for the slight, wiry frame it

surmounted. . . . His keen, restless, piercing blue eyes . . . and the

ceaseless and expressive activity of his fingers . . . betrayed a

temperament which could not brook inaction. The chin was long and rather

broad. The lips, firmly pressed together, were in constant motion, with

which the twinkling of the eyes seemed to keep time, giving an

appearance of unrest to the whole countenance.”

Shortly after

Mackenzie’s settlement in York a mob of young men connected with the

officials invaded his newspaper office, broke his press and scattered

his type, flinging some of it into the bay. The somewhat un-looked-for

result of the outrage was to extricate the enterprising editor from

financial difficulties, for he was awarded heavy damages. Soon

afterwards, without waiting for an invitation from anybody, Mackenzie

announced himself as a candidate at the approaching election for one of

the two seats for York County. At the same time he declared that,

contrary to the all but universal practice of the period, he would “keep

no open houses” and “hire no vehicles to trundle freemen to the hustings

to serve themselves.” His daring was justified by success. He and Jesse

Ketchuin, the philanthropic tanner, found themselves at the head of the

poll. A little later Mackenzie’s repeated expulsions from the House kept

the county in a ferment, and Dr. Scadding, in his Toronto of Old,

recalls seeing a crowd pelting Mackenzie in the old Court House Square

with “the missiles which mobs usually adopt.” On the same day, when

Jesse Ketchum was haranguing the throng from a farmer’s wagon, some

sturdy fellows suddenly laid hold of the vehicle and wheeled it rapidly

down King Street, nearly throwing the speaker off his balance.

At another time,

Mackenzie, “after one of his reelections," was “borne aloft in triumph

on a kind of pyramidal car,” with a massive golden chain, the gift of

his admirers, about his neck, whilst in the procession was a

printing-press “at work in a low sleigh, throwing off hand-bills,” which

were tossed to right and left into the attendant crowd.

Year by year the plot

thickened. Despairing of any redress of their grievances, the more

ardent of the Reformers began to think of emulating the example of the

"American Patriots,” of Revolutionary memory, and declaring for

independence. The theatrical indiscretions of Sir Francis Bond Head made

bad worse, and at the end of July 1837 there was a meeting of the

disaffected in a Bay Street brewery, at which a Declaration of

Independence was adopted, and then Mackenzie went out into the country,

holding meetings at Newmarket and, it is said, at some two hundred other

places, to organise vigilance committees and prepare for revolt. He did

not by any means confine his labours to York County, but when the

attempt on Toronto was determined on, Montgomery’s Tavern, on Yonge

Street, a few miles from the city, was appointed as the rendezvous for

the rebels; and it was there that they were completely defeated by the

loyal forces. After that, for over a decade, Mackenzie disappeared from

the county, and, though his return to Toronto in 1849 was the signal for

rioting on the part of some hot-headed Tories, and for the burning of

the effigies of Attorney-General Baldwin, Solicitor-General Blake and

Mackenzie himself, he was a worn and broken man, and never again played

his former energetic part.

At the time of his

return, Lord Elgin was Governor-General. In private life he appeared as

“an unassuming, good old gentleman,” and was often seen “walking arm in

arm with his wife in the good old-fashioned way,” but he used to go in

state to open or prorogue the House, in his Viceregal chariot, drawn by

a "gaily caparisoned four-in-hand,” and attended by a “full complement

of postilions.” Mr. Yeigh tells of many famous scenes in the old

Parliament buildings on Front Street, as when George Brown, in April

1857, introduced his motion declaring for “Representation by

Population,” or when John A. Macdonald, violently attacked by the

brilliant Irishman D’Arcy M'Gee, calmly went on sealing a pile of

letters with wax, as if absolutely deaf to the storm raging about his

head.

After the union of the

Canadas, when the Legislature sat in Montreal, the building was put to

other uses, serving at one time as a medical school in connection with

King’s College, and at another as a lunatic asylum, after which it was

reoccupied by the Parliament of the United Provinces. Next it was used

as military barracks, but from Confederation until 1892, when the new

Parliament buildings in Queen’s Park were ready for occupation, it was

the home of the Legislature of the Province of Ontario.

Reading its old

history, one gets the impression that the capital of Upper Canada was

always a lively, stirring place, and though John Galt was unkind enough

to refer to it in terms implying that it was superlatively dull, from

the first it had one great advantage, apart from its position as

capital. It was comparatively easy of access, for in pre-railway days it

was served by numerous sailing vessels and steamers. (The first steamer

to ply on Lake Ontario was built in 1816.) Then, as already mentioned,

York town and York County were far better off for roads in the early

day’s than most pioneer communities. The importance of Yonge Street as a

route towards the upper lakes was recognised in a practical fashion by

the old “North-west Company,” which in 1799 gave £12,000 “towards making

Yonge Street a good road.”

Towards the middle of

the nineteenth century the demand for good roads became secondary to the

agitation for railways. The first of the iron roads upon which an engine

ever ran in Upper Canada was the Northern Railway, which was cut through

the centre of the county. The first sod was turned by the Earl of Elgin

on October 14, 1851, but the line was not opened for traffic throughout

its ninety-five miles of length till New Year’s Day, 1855. |