|

“Where once the pagan

rite was seen,

Or French or Indian warlike bands,

Where fratricidal strife had been,

Two Christian nations now clasp hands.”

Janet Oarnochan.

WE have all beard the

oft-repeated sneer that “Canada has no history,” but the story of this

one county, if it could be told at all adequately, would effectually

disprove the assertion. The trouble in writing of Lincoln is not paucity

of historic material, but difficulty of selection from an embarrassment

of riches. From the days of La Salle onward, the district about Niagara

has supplied many a vivid page to the history of Canada. Like Quebec in

Lower Canada, it is in our upper Province the chosen home of romance.

Now cultured and fruitful and peaceful as a very garden, the peninsula,

three parts surrounded by the mighty lakes and the majestic river, has

formed a background for the deeds of heroes and lor the intricate play

of the most varied human activities.

During the

Revolutionary War that grim Loyalist, Butler, and the noted Mohawk,

Joseph Brant, wintered several times at Niagara, and when peace was made

Butler’s disbanded “Rangers” settled along lake shores and river bank,

to begin a bloodless warfare on the great trees which seemed to them

little better than “cumbered of the ground.” In the struggle to subdue

the earth and to make homes in the wilderness for their large families

of children (sometimes numbering twelve, sixteen, and even twenty lads

and lasses), not only the military pioneers but their stout-hearted

wives proved their mettle. Slowly they triumphed over their

difficulties, but the records of the old churches hint that the

hardships and privations and perhaps ignorances of the time were too

much for many a tender little blossom of humanity, and, more even than

in our own day, babies were born but to die in a few weeks or months.

Those hardy enough to struggle through the first year or two often grew

up strong and sturdy, able (both men and women) to bear burdens and to

toil fur hours, which would make their descendants think themselves

greatly ill-used.

At first, the

new-comers lived under something like martial law, but the Loyalists,

notwithstanding traditions to the contrary, were as much in love with

liberty as their brethren who had driven them from their old homes, and

they appealed —not in vain—for British law.

It was a great day in

little Niagara (or Newark), the chief settlement of Lincoln (then a much

more extensive county than to-day), when Governor Simcoe opened there

the first Parliament of Upper Canada. It is sometimes said that the

ceremony took place under a tree, but the fact is that the importance of

the occasion was marked by all possible pomp and ceremony. That first

meeting of the Legislature of our Province took place in the Indian

Council House, on a hill above the river. The Governor, stately and

gorgeous in his military uniform, was attended by soldiers from Fort

Niagara as a guard of honour, and right royally he played his part that

day as the representative of the Sovereign, while the guns from the fort

and the shipping in the mer boomed out their sonorous applause.

For five successive

years, (until the giving up of Fort Niagara, on the opposite side of the

river to the Americans, threatened the security of the town) Parliament

met at Newark; but long after it ceased to be capital its geographical

position, and perhaps the character of its early settlers, ensured the

continuance of its eager, stirring life. Many an old-time visitor to

Canada has a good word to say for the busy little frontier town and its

“very agreeable” society, which was indeed composed to a remarkable

degree of people of a fine type, who had energy to spare for the things

of the mind and the spirit, despite the pressure of the material needs

of a pioneer community.

The records of the

Anglican Church of St. Mark and the Presbyterian Church of St. Andrew,

beginning respectively in 1792 and 1794, have been lovingly studied and

interpreted by Miss Janet Carnochan, whose various papers on Niagara

give many a glimpse into those old days. During the War of 1812 St.

Mark’s was used as a hospital by the British and as a barracks by the

Americans. In the churchyard are still to be seen traces of rifle-pits,

and a large tombstone, hacked and broken, shows evidence of having been

used by the soldiery as “a butcher’s block.” As for the church, only its

solid stone walls escaped destruction when the town was set on fire by

the Americans in 1813 on that

“day of fear and dread

When winter snow robed dale and down,

And mothers with their children fled

In terror from the burning town.”

Soon after the war it

was restored, and "the picturesque grey-stone church, with its

projecting buttresses and square tower peeping through the branches of

magnificent old trees,” still stands. The Presbyterian church, though

built in 1795 of extraordinarily solid timbers, was totally destroyed in

the conflagration, and the later St. Andrew’s, now guarded “by a belt of

solemn pines,” was not begun for seventeen years after the war. Another

early church of the county which did duty as a hospital when the country

was invaded was that at Twelve-mile Creek, near St. Catherine’s, now the

county seat.

There were not a few

book-loving folk about Niagara in its early days, and the little town

has to its credit not only the publishing of the first newspaper in the

Province, in 1793, and the formation of the first agricultural society,

but also the foundation of the first public library. The fact had been

long forgotten, when an old record fell into Miss Carnochan’s hands,

which told the whole story from its foundation in 1800 to its

dissolution nearly twenty years later, after having been sadly “wasted”

in the time of the American occupation. It was supported by

subscriptions, and during the course of its existence nearly a thousand

volumes were bought, at a cost of over five hundred pounds. It was

strong in works on history and agriculture and other grave subjects, but

was more sparsely supplied with works of fiction and poetry. In those

days books were an expensive luxury, bat the trustees of the library did

not scruple to pay six guineas for a Life of Pitt, or, which is more

surprising, half as much for Jane Porter’s Scottish Chiefs. After this

library was scattered the congregation of St. Andrew’s established one

which ultimately numbered over nine hundred volumes; and there is still

in existence a most valuable collection of books sent out from England

to the first clergyman of St. Mark’s and presented to the church by his

heirs. Fortunately, when Niagara was burned in 1813, these books were at

a log-house, called Lake Lodge, about three miles out of the town.

But it was not only the

taste for books that gave savour to life at Niagara. The little group of

people gathered in the wilderness had come from the ends of the earth,

and there was a constant change in the personnel of society in all

ranks. There was much coming and going of soldiers and officers, and,

for a time, of the Government officials. Governor Simcoe, with his

vivacious Welsh wife, long made it his headquarters, and that alone

brought many visitors and settlers to Niagara. A misty figure in the

traditionary lore of old Niagara was “the old French Count”; but

investigation has proved him to have been a very real, very human

personage, who lived through as many misfortunes and adventures as any

hero of romance. The Count de Puisaye was conspicuous amongst the crowd

of noblemen to whom the French Revolution brought disaster, and his name

appears in every history of that dread time, “The Reign of Terror.” At

first he had taken the popular side, but alarmed at the excesses of its

leaders had set himself in 1792 to raise an army to aid the king. A

price was set on his head, and he was obliged to flee. With the help of

the English Government, a rising in Brittany was organised, and De

Puisaye was one of the leaders. The attempt ended in disaster, and De

Puisaye spent months in concealment in a cavern in the woods of

Brittany. Failing to raise another force, he planned to lead a military

colony of French Royalists to Canada, and received a promise of lands

and assistance from the British Government. Only forty Royalists joined

him, and this scheme too was a failure, though for a time the French

Countess de Reaupoil dazzled society at York with her jewels, while De

Puisaye and other noble gentlemen shed lustre on the social gatherings

at Niagara and elsewhere. Clever, ambitious, graceful in manner and

person, strangely dogged by misfortune, the gallant Count seemed formed

to be a hero of romance; but, alas for him, it was a romance with a

dismal ending, for after a few years in Canada, he returned to England

to drag out his last years in exile and loneliness.

Of all the notable

people who at one time or other have had a connection with Lincoln

County, perhaps, in the eyes of Canadians, the imposing figure of Isaac

Brock looms largest. Born at St. Peter’s Port, Guernsey, “the hero of

Upper Canada” was the eighth son of a family of fourteen children. Even

as a boy he was very tall, strong, and athletic. At fifteen he obtained

a commission in the army, and before he was twenty-nine had attained the

rank of Lieutenant-colonel. He saw active service on the continent of

Europe during Napoleon's wars, but it was in our own land that he gained

his lasting fame. It was not a little thing that in those days of

terrible severity, when three subordinate officers could order a man to

receive "999 lashes with a ‘cat’ steeped in brine,” that Brock won the

love of his men. Yet he could be stern enough upon occasion.

Soon after his arrival

in Canada, he visited Niagara under strange circumstances. He was at

York when he heard that six deserters had gone off with a Government

bateau across the lake, and at midnight he started in pursuit in an open

boat with a crew of twelve men. “It was a hard pull of over thirty

miles,” but Brock took his turn at the oar, and the deserters were duly

captured.

A few months later news

came that a plot was on foot at Fort George to murder the commanding

officer, Sheaffe; and again, without an hour’s delay, Brock crossed the

lake, walked quietly into the barrack square, found some of the

suspected men on guard, and had them handcuffed and marched off to the

cells before they could take breath. Four of the mutineers and three

deserters were shot at Quebec, and Brock, assembling the garrison at

Fort George, read the account of the execution, but he added, in a voice

that trembled, “Since I have had the honour to wear the British uniform

I have never felt

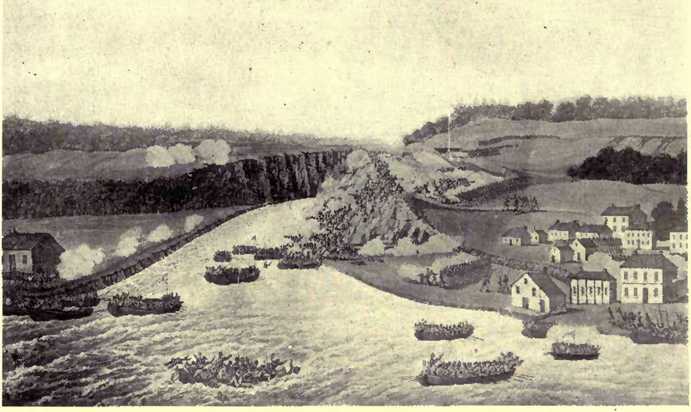

BATTLE OF QUEENSTON 1813

grief like this”; and

when he took command at Foit George there were no more desertions.

Brock was a good friend

and a true-hearted brother (as there are many incidents to show), as

well as a great soldier. At first he found life at Niagara somewhat

dull, and “would travel the worst road in the country—fit only for an

Indian mail-carrier—to mix in the society of York.” But he did his share

to enliven the little town, giving annually a ball, which was one of the

events of the season. Perhaps one of the attractions that drew him to

York was the fact that "a log mansion” on the outskirts of that little

capital was the home of a young lad}- named Sophia Shaw, to whom he

became engaged. Often, however, she used to go to visit a sister who

lived near Niagara.

Mr. Nursey, in his

vigorous and picturesque Story of Isaac Brock, says that a vast quantity

of freight was sent up from Kingston to Queenston, “the remote

North-west looking to Niagara for food and clothing—the return cargoes

being furs and grain.” The goods were carried in farmers’ wagons round

the Falls, “and the entire length of the portage from Lake Ontario to

Lake Erie was practically a street,” full of bustle and activity. “A

quite pretentious wharf lined the river, and from this on any summer

afternoon a string of soldiers and idle citizens might be seen—casting

hook and troll for bass, trout, pickerel and herring, with which the

river swarmed.” Once Brock himself helped “to haul up a seine-net in

which were 1008 white-fish of an average weight of two pounds, 6000

being netted in one day.”

But all the time while

Brock was in Canada the storm-clouds of the coming war were slowly

gathering. For years he was trying to prepare for the tempest, and

before il broke fie was appointed head both of the forces and the civil

government in Upper Canada When war was declared, more men than he could

clothe and arm rallied to his standard, but in all Canada there were

less than 1500 regularly trained soldiers, and the whole population of

the two Provinces could have been packed into a city of the size of

present-day Toronto, whilst the United States had 8,000,000 people.

Moreover, Brock, subject to the orders of his far less able superior

officer, Sir George Provost, had not a free hand; but, in spite of all

drawbacks, his success at Detroit and his personality inspired the

hard-pressed Canadians with such confidence that he fairly earned the

title, with which he was greeted everywhere on his return from the west,

of “the saviour of Upper Canada." By an odd coincidence the bells in

England clanged out upon h's birthday for the capture of Detroit, and a

knighthood was bestowed upon Brock, but he never knew it, for before the

news reached Canada he had gone up to fight and fall on Queenston

Heights.

I have no space—nor is

there need—to tell again the story of that grim battle for the

possession of the Heights; nor of the first burial of Brock and his

gallant aide, Macdonnell, in a grave within a bastion of Fort George,

soon to be desecrated by the footsteps of the invaders; nor of the

building and destruction (in 1840) of the first monument, and of the

gathering in that year of a mighty concourse of thousands to testify to

their admiration for the dead hero and their love of British

institutions; nor of the erection of the tall shaft beneath which

Brock’s remains, three times disturbed, have now rested in peace for all

but sixty years.

We must pass on to

speak of a building, erected in old Niagara soon after the war, to which

cling as many historic associations as to the remaining vestiges of Fort

George and to old St. Mark’s. I refer to Niagara’s second jail and court

house, once counted the handsomest building in Upper Canada, and

transformed in 18G6 from a grim abode of misery and despair to a house

of hope, for in that year it was bought by Miss Rye to shelter the

little English waifs to whom she was giving a new chance in Canada; and

the court-room, which had witnessed many exciting trials, became a

dormitory’.

Here, on an August day

in 1819, assembled a huge crowd to witness the trial of Robert Gourlay,

self-elected champion of liberty and good government, whom some of the

officials were determined to crush. At the time they seemed to triumph,

not only driving Gourlay into banishment, but daring also to condemn the

editor of The Niagara Spectator, in which had been printed a letter of

Gourlay’s, to a punishment of unheard-of severity. This included a line

of fifty pounds, an hour in the pillory, eighteen months’ imprisonment,

and the obligation, under peril of a debtor’s prison, to give for seven

years a security of a thousand pounds. This sort of thing, however, only

provoked the advocates of justice to go to greater lengths.

In 1824 William Lyon

Mackenzie began at Queenston to edit The Colonial Advocate, dragging

abuses into the light and agitating for reform so unceasingly and

fervently that he worked up himself and his followers into such a state

that rebellion seemed the only hope of remedy. But there was no Canadian

revolution, and on another August day, in 1838, the court house was

again packed, while the judge, to the horror of many present, pronounced

on two of the captured rebels the terrible old sentence for treason.

Then were heartbreaking interviews with the prisoners through the narrow

grating of the tomblike condemned cell. But at last, when all was ready

for that dreadful hanging and quartering, the town was thrilled by the

news that just in time had come a respite, won by two brave women,

Wait’s young wife and Chandler’s daughter, who had made a hasty,

difficult journey of seven hundred miles to Quebec to appeal to Lord

Durham himself.

A year earlier Niagara

had witnessed a desperate struggle to save an escaped slave from being

cast out of the land of freedom, to which, when the Southern States were

slave States, many a negro steered his course by the light of the North

Star. A charge of robbery against the slave was the master’s excuse for

demanding his extradition, and the authorities of Upper Canada allowed

it. But, led by Holmes, a coloured preacher, the negroes, hundreds

strong, guarded the jail, and finally, at the cost of two lives,

succeeded in rescuing the man from the Sheriff as he was being taken to

the frontier. It is good to know that at last the slave reached England

safely, and so got beyond his master's reach. |