|

“Over the hillsides the

wild knell is tolling,

From their far hamlets the yeomanry come;

As through the storm-clouds the thunderburst rolling,

Circles the beat of the mustering drum.”

O. W. Holmes.

THIS fair and

extraordinarily fruitful region of farms and orchards (for over half a

century included within the bounds of Lincoln County) has a chequered

history of war and peace, of struggle and achievement. During the War of

1812 Welland shared with its parent county the perilous honour of being

again and again the battle-ground upon which the defenders of our land

staunchly resisted the invaders. It is not possible to tell in detail

the story of the struggle, even as it specially' touched Welland; but no

sketch of the county’s history would be worthy' of the name which passed

over those brave old days in silence. No episode in the three years’ war

is more dramatic than the “Battle in the Beech-woods” at “Beaverdams,”

and, though the opening scene of the drama had Queenston for a stage,

the fifth act was played out in what is now Welland County, as is

testified by a monument near the railway station of Thorold. This

British victory, as no Canadian needs to be told, has a heroine as well

as a hero, and, throughout, it was a triumph not of superior force, but

of keen wit.

In the early summer of

1813 the gallant Irishman, Lieutenant FitzGibbon, with a small party of

daring followers, was finding a multitude of ways of rendering himself

annoying to the Americans, who had seized upon Niagara and made it their

headquarters. He so distinguished himself that at last the American

Colonel, Boerstler, was ordered to take some five hundred men to

surprise him at his post at Beaverdams, but a couple of officers

ventured to discuss the scheme in the hearing of Laura Secord. Daughter

of a Loyalist, wife of a militiaman (still disabled by a wound received

at Queenston Heights), mistress of the house to which the body of

General Brock had been carried after he fell, she was every inch a

patriot, and when the Americans rose from the table where the quiet

woman had been ministering to their wants the plan was foredoomed to

failure.

Very early next morning

Laura Secord passed the invaders’ sentries by means of a ruse, and set

out on a twenty-mile walk to put FitzGibbon on his guard. The enemy held

the roads, so Laura plunged into the woods, to toil all the long day by

blazed trails, through swamps and over fallen trees, across creeks

swollen to torrents by recent rains, to come out at dusk in a clearing

on the outskirts of FitzGibbon’s camp, and to find herself surrounded by

a horde of painted, yelling Indians. Weary, dishevelled, but

high-hearted still, she made the chief understand by signs that she must

speak to the British leader.

At once the valiant

Irishman fell into the spirit of the thing. Outnumbered by something

like ten to one, he might have been content to beat a masterly retreat.

Instead, he stood his ground, bent on the capture of his would-be

captors, and so posted his Indian allies that when the Americans entered

the beechwoods, weary from the march and unnerved by the disquieting

attentions of a troop of Indians who had hung on their rear, they were

greeted with a pandemonium of yells and screeches and dropping shots.

Prompt surrender seemed then the better part of valour, yet it taxed

FitzGibbon’s Irish wit and audacity to the utmost to keep the perilous

secret of his troops’ scanty numbers.

From the British point

of view, the affair at Beaver-dams was a cheerful little burlesque, but

Welland County had its share of the grimmest side of war. In those

unquiet years many a farmhouse went up in smoke and flame. Early in July

1814, an American force took possession of Fort Erie, and defeated the

British On the banks of Chippewa Creek. Soon afterwards both armies

received reinforcements, and the British took up a strong position near

the Falls of Niagara, at the end of a narrow road called Lundy’s Lane.

Their guns commanded the lane, but the Americans attacked them

furiously. It was late in July, and the battle, beginning at six in the

evening, raged, with a brief lull, till after midnight. The opposing

guns roared almost mouth to mouth, drowning for the time the mighty

voice of the great cataract. Sometimes a fitful gleam of moonlight shone

down on the combatants, but for the most part the struggle was shrouded

in the black darkness of a cloudy night. In this battle the carnage was

greater than in any other during the war, but the smaller British force

held their ground, and the Americans retreated to Fort Erie, where they

were besieged in vain by the British. At last, however, they blew up the

fortifications and returned to their own country.

Twenty-three years

later, in 1837, William Lyon Mackenzie, after a futile attempt to

overturn the Canadian Government, fled to the United States, only to

venture back into British territory, with a few followers, whom he

called the *Patriot Army.” Making Navy Island, in the Niagara River, row

part of Welland County, his headquarters, he set up a “provisional

government," offered a reward of five hundred dollars for the capture of

Sir Francis Head, and promised land grants to all who would aid in the

conquest of Canada. For several days the “provisional government,” was

suffered to rule undisturbed In Navy Island, then Colonel M'Nab, with a

force of loyal volunteers, determined to capture the little steamer

Caroline, which the rebels used for carrying over supplies from the

mainland. Accordingly, after dark on December 29th, a few brave

volunteers crossed the rapid river to the wharf where the vessel lay,

drove the crew ashore, and, setting the boat on fire, towed it out into

the current. The blazing vessel cast a red light on the rushing waters,

then suddenly sank, and all was black. Colonel M'Nab was knighted for

this exploit, but as the Caroline was the property of American owners it

caused a great outcry in the United States.

The rebels held Navy

Island for a month, secure against musket shot in the protection of its

woods, but when heavy guns were cent up from the St. Lawrence they

hastily retired across the boundary.

A generation later, in

1866, the township of Bertie was invaded by 900 armed “Fenians” and

sympathisers, many of whom had served in the American Civil War. They

made a raid on the village of Fort Erie, tore up the railway tracks, cut

the telegraph wires, and marched westward. A few regulars and some

companies of “the Queen’s Own ” and other volunteers from Toronto and

Hamilton were promptly sent to look after them, but owing to some

mistake the volunteers were hurried forward in advance of the regulars,

and, falling in with the Fenians at Ridgeway, were ordered to attack.

Under the fierce onslaught of the Canadians, many of them young lads,

the Fenians wavered. Then they rallied and poured a murderous fire on

their assailants, killing nine, wounding thirty, and forcing the rest to

retire; but O’Neil did not care to stand up against the regulars, and

that same night he and his marauders made the best of their way out of

Canada.

But even in Welland

such conflicts between man and man were only episodes in the greater

struggle, which has lasted now for well over a century, “ to replenish

the earth and subdue it,” and sometimes the early settlers “builded

better than they knew.” For instance, it is

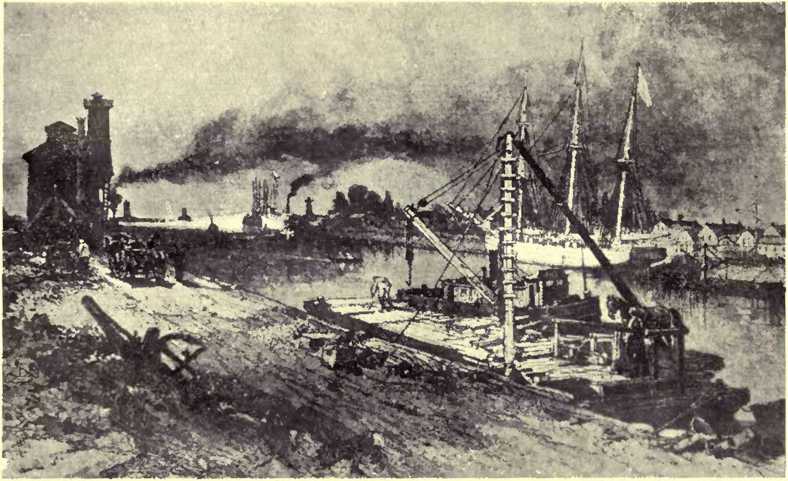

PORT COLBORNE NEAR ENTRANCE TO WELLAND CANAL

told that the idea of

cutting the Welland Canal (which, besides its use as a waterway,

supplies water for scores of factories and workshops) arose from the

desire of its promoter, William Hamilton Merritt, to secure for his mill

a water-supply which would not fail in dry weather. Soon, however, he

grasped the full significance of his idea, and, getting his neighbours

to help him, made the first rough survey for the canal. That was in

1818, and for half a dozen years Merritt worked unceasingly to interest

the Government and the capitalists in his project. The result was that

it was finally taken up by a private company, with a Welland County man,

George Keefer, as its first president. In 1824 the first sod of the

canal was turned; and in 1829 hundreds of people gathered at St.

Catharines (of which city it has been the making) to see two vessels

gaily decorated with flags pass up the new waterway towards Lake Erie.

Since then it has been several times enlarged, and has been taken over

by the Government, which is now constructing a larger and deeper Welland

Canal. Through the present one, however, there passes annually something

over two million tons of freight.

Last but not least of

the distinctions of Welland County, its boundary takes in the Horseshoe

Falls of Niagara, and owing to this its soil has been trodden by every

visitor of distinction—artists, authors, poets, statesmen, princes—since

the days when the only access to the foot of the cataract was by “ an

Indian ladder ” or pine tree, with branches lopped off near the trunk.

To these and to thousands and thousands of other men and women the

mighty cataract has spoken messages of awe and wonder and delight; and

now, in this last decade, man has found a way to make a servant of “the

Thunderer of Waters,’’ and Niagara power turns his wheels and lights his

streets not in Welland County only, but in a dozen others.

The History of the

County of Welland (pdf) |