|

“Our hearts are as free

as the rivers that flow

To the seas where the north star shines,

Our lives are as free as the breezes that blow

Thro’ the crests of our native pines.”

Robert K. Kernighan

THE map of Algoma shows

a vast territory, stretching some three hundred and sixty miles

northwards from “the Soo” to the Albany River. Its southern portion is

checkered with townships, already numerous enough to make several

counties after the pattern of those of old Ontario, but bearing a small

proportion to the huge blank spaces of the north, marked only with the

names of the lakes and rivers that plentifully water that “Great Lone

Land.” The lines of the townships run on the north into the larger

oblong of the Mississauga Forest Reserve. Indirectly the Canadian

Pacific Railway’s advertising agents had a hand in the setting apart of

the vast reserve by calling the attention of "canoe travellers” to the

Mississauga River. This flows through a large block of pine timber, and

the authorities, fearing that the coming of tourists would cause

increased danger of forest fires, decided to take measures to protect

the valuable pine. Accordingly, on February 24, 1904, an Order in

Council was passed, creating the Mississauga Forest Reserve, which

comprised about 2900 square miles.

Dotted along Algoma’s

two hundred miles or more of coast-line on Lakes Huron and Superior are

a few villages and towns, the largest and most important of which is the

historic Sault Ste. Marie, It was first visited, says Dr Bain, by the

French traders, who named the Indians Saulteaux, from the falls in the

St. Mary’s River.” Jesuit Fathers soon followed, and P6re Marquette

established a mission there in 1669. Two years later the Intendant Talon

sent Daumont de St. Lusson, accompanied by the interpreter, Perrot, to

seek for the copper mines, of which there were rumours, on Lake

Superior. The expenses of the expedition were to be paid by trading in

furs. St. Lusson wintered with the Indians, claiming in the name of his

Sovereign the whole land as far as the western and southern and northern

seas. As a visible token of these stupendous claims, a cross bearing the

Royal Arms was planted at Sault Ste. Marie, and the Jesuit Allouex

harangued the assembled Indians, representing several tribes, on the

power of the King of France. But the red men, probably actuated by

superstitious fears, pulled down the cross as soon as the backs of the

French were turned.

The troublesome

Iroquois caused the abandonment of the mission in 1689. Sixty-one years

later, La Jonqidere, then Governor of Canada, gave his nephew and the

Chevalier de Repentigny a grant six leagues square at Sault Ste. Marie,

so that—“at their own expense”— they might build a palisade fort to

prevent the Indians trading with the English. “The palisade was 110 feet

each way,” and enclosed three small houses and a “redoubt of oak 12 feet

square.” A Canadian, Jean Baptiste Caueau, or Cadot, was put in charge;

and there, long after the French lilies "had ceased to float over the

ramparts of Quebec,” this trader kept the old flag flying by St. Mary’s

River, though ultimately he accepted the changed situation, and even

fought gallantly for England. He had married an Indian woman “of great

force of character, energy, and uprightness,’’ and in his house only

Chippewa was spoken.

Alexander Henry visited

Cadot in 1762, and this notable trader and explorer was much interested

by the spectacle of the Indians—two in each canoe—scooping up whitefish

with a long-handled net from the turbulent waters of the rapids. At

times the fish (some of which weighed 15 lbs.) were so crowded together

in the water that a skilful fisherman could catch five hundred in two

hours, but some winters the usual supply of fish failed, and the traders

and Indians - had hard work to fight off starvation. Henry was at

Michillimackmac, or Mackinaw, during Pontiac’s war, when the fort was

taken by the Indians, but after many hair-breadth escapes he fell in

with Madame Cadot, who was on a journey, and with her reached Sault Ste.

Marie in safety. Two years later Henry took Cadot into partnership.

The story of the first

success in the War of 1812 belongs, in a sense, to the district of

Algoma. On St. Joseph's Island there was at that time a blockhouse

commanded by Captain Roberts, to whom Brock had sent orders that if war

were declared he was immediately to attack the American fort at

Mackinaw. Roberis had only forty-five regular soldiers available, but

traders and voyageurs eagerly volunteered, and the North-west Company

furnished the brig Caledonia as a transport. The surprise was so

complete that there was no bloodshed, and Mackinaw remained in British

hands till the end of the war.

Amongst the volunteers

was John Johnston, a well-to-do Irish trader of Sault Ste, Marie, who

had wedded a Chippewa, During his absence his house was raided and burnt

by Americans, while his wife and children looked on from the woods.

Later he took his wife and a daughter, a beautiful girl, home to

England. The Duke and Duchess of Northumberland were so charmed with the

latter that they wished to adopt her, but she preferred to return home,

and ultimately became the wife of Henry Schoolcraft, the famous

historian of the Indian tribes.

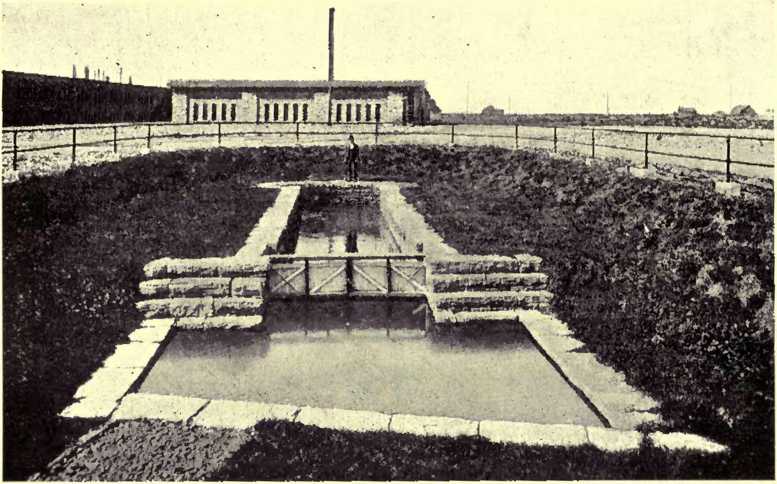

THE OLD LOCK AT SAULT ST. MARIE

Another pioneer who

took part in Roberts’ expedition, and had also married an Indian woman,

was Charles Ermatinger, a trader, of Swiss extraction. His post was on

the south side of the river, and in 1822 the Americans took possession

of it and made it into a fort, but afterwards gave compensation to its

owner, who had removed to the British side.

In the days of trouble

between the North-west Company and the X. Y. Company there was a hot

dispute over the portage past the rapids. The latter company, says Dr.

Bryce, “forced a road through the disputed river-frontage, while the

North-west Company used a canal half a mile long on which was built a

lock, and at the foot of the canal a good wharf and store.” Remains of

the tiny old lock are still to be seen, near an old blockhouse lately

used by the directors of the Algoma Steel Company for a lunch-room. The

voyageurs in their little boats often had perilous voyages along the

rugged coast of Lake Superior, to which clung many a legend of terror,

and not a few bold fellows went down to death in its chill depths. Here

and there along its grim shores were dotted little trading posts, that

at Michipicoten, where Henry once tried unsuccessfully to grow potatoes,

being within a few miles of what is now the western boundary of Algoma.

In 1870, when the Red

River expedition was working its difficult way westward, there was no

Canadian canal at Sault Ste. Marie by which vessels could pass the

rapids, and the Americans would not at first permit the force to use

their canal, built in 185 5, so guns and stores had all to be “portaged”

three miles and a half. After urgent remonstrances, however, the embargo

was removed, and then the American officers at Fort Brady became very

civil to the British officers. Of course, when the troops had embarked

for Sault Ste. Marie, that stately name was often on the lips of the

officers, and it was told that the old skipper of one of the steamboats

grew obviously uncomfortable at its repetition, and at last protested:

“Call it the Soo, sir—the Soo! . . . We always calls it the Soo; it’s

ever so much shorter, and everyone will understand ye!” And “the Soo” it

most often is to this day, when its population has passed 11,000. and

when millions of dollars are invested in its huge iron and steel works,

its great paper factories, and other vast industrial enterprises, to say

nothing of its world-famous canal.

To many people, indeed,

the canals are the most interesting feature of "the Soo.” It was in 1888

that the Dominion Parliament passed a measure for the building of the

canal which was to make Canada independent of the good-will of her

neighbour for the passage of her vessels between Lake Huron and Lake

Superior. Plans were at once prepared, but the engineer died before they

could be carried into effect.

For the lock the final

design was made in the autumn of 1892, and the contractors agreed to

complete it by 1894. But in the summer of 1893 the United States

Government ordered the collection of tolls on all vessels passing

through the American lock. Upon this the Dominion Government offered the

contractors a bonus of $90,000 to complete the work by the end of the

year, and, except for a very small portion, the whole of the walls of

the lock, from 20 to 25 feet in thickness, was built in five months, the

last stone being put in place on November 16, 1893. The lock is 40 feet

deep, 60 feet wide, and 900 feet long. Vessels go through as well by

night as day, only fog, which sometimes makes it hard to find the narrow

channel leading to the lock, stopping the procession. The canals on both

sides of the international boundary are now free to the vessels of both

nations. The larger vessels, however, often choose the Canadian canal,

and the tonnage which annually passes through it is three times as great

as that passing through the Suez Canal. |