|

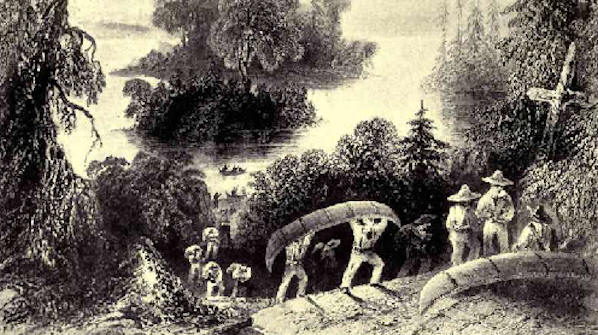

“Through tangled

forests, and through dangerous ways;

Where beasts with man divided empire claim,

And the brown Indian marks with murderous aim.”

Goldsmith.

THIS district has a

name which, though picturesque, appears to convey a reflection upon its

climate. In reality, however, the name was not intended to do this, but

was given by the French traders in the lake and stream, as “Lac* and

“Riviere a la Pluie,” because they were connected by a perpendicular

waterfall of such force that it raised a mist like rain. The voyageurs

frequently seized upon such striking natural features to distinguish

places in the wilderness, and it was they who dubbed the cataract itself

the "Chaudiere,” or “Caldron,” as the falls on the Ottawa were named

earlier.

It is 225 years since a

young Frenchman, Jacques de Noyon, wintered, it is supposed, at the

mouth of the Rainy River, where he heard from the Indians of a nation of

dwarfs, “three and a half or four feet tall and very stout,” and of

cities to the west inhabited by white men with beards, and of ships that

fired great guns. Probably De Noyon reached the Lake of the Woods, but

he did not discover the Indians’ land of marvels. A few years later a

French officer, La Noue, was sent to establish a trading-post on Rainy

Lake, with a view of intercepting the furs carried to the English on

Hudson Bay.

In 1731, La Wrendrye,

beginning his western explorations, sent his nephew, La Jemeraye, to

build a fort for him on Rainy Lake. After some difficulty in persuading

men to go with him, not only on account of the long and difficult

portages but also for fear, it is said, of the demons that were supposed

to haunt the little-known western solitudes, the young mail succeeded in

building Fort St. Pierre, as he named the new post in honour of his

uncle. After wintering there he returned with a rich harvest of furs,

and, cheered by this good fortune, La Verendrye and the rest of the

party proceeded to the new fort, which was situated in a delightful

meadow, surrounded by a grove of oaks. After a short rest, the leader

pushed on to the Lake of the Woods, escorted by a flotilla of fifty

Indian canoes. On a peninsula, running far into the lake from its

western shore (now Manitoba), was built another post, Fort St. Charles,

consisting of a quadruple oblong of posts, from twelve to fifteen feet

high, which enclosed several log-cabins. It was an excellent spot for

the fur trade, and for several years La Verendrye, though he had by no

means given up hope of pursuing his journey westward, made it his

headquarters. Once he had to travel back to Montreal to persuade the

merchants there to furnish him with additional supplies. Returning, he

hastened forward in a light canoe, to find his people at Fort St.

Charles approaching the starvation point. Then came his son Jean, from

Lake Winnipeg, to report the death of La jemeraye, and it was decided to

send the young man with some of the most active of the voyageurs to meet

and hasten the provision boats. A Jesuit, Father Aulneau, joined the

party, which started from the fort very early one morning. But, a day or

two later, the supply boats arrived, and their crews reported that they

had seen nothing of Jean and his comrades. At once, the anxious father

sent out a search-party, and horrible was the discovery that they made.

On a little island, off

what is now known as Oak Point, guarding the entrance to the Rainy

River, the headless bodies of the whole company were found lying in a

circle on the beach, where it was supposed that they had stopped to

breakfast, and had been attacked suddenly by a band of Sioux. Afterwards

it leaked oat that, during La Vrendrye’s absence, a party of Sioux

visiting Fort St. Charles had been fired upon by some Crees who happened

to be within. The French got the credit of this piece of treachery, and

upon the French the Sioux took the first opportunity of wreaking

vengeance. La Verendrye’s Indian allies pressed him to make war on the

murderous Sioux, and at first the gallant Frenchman was sorely tempted

to take their advice; but he knew that, if he did so, it was “good-bye”

to all his plans of exploration, so he finally laid aside any thought of

retaliation.

About 1765, the Indians

of Rainy Lake made themselves so obnoxious to the traders, by plundering

them of their goods and demanding blackmail, that they earned the name

of “the Pillagers.” Two notable traders of Montreal, Benjamin and James

Frobisher, suffered much at the hands of these thievish Indians, on

their first expedition; but afterwards, by “a show of force and

co-operation” with other traders, they managed to get their goods safely

through the dangerous country.

The names of many

remarkable men amongst the traders are connected with the Rainy River

District. The elder and the younger Alexander Henry (uncle and nephew),

David Thompson and Daniel Williams Harmon, all travelled by way of Rainy

Lake and the Lake of the Woods westward. The last-mentioned traveller,

when he reached Rainy River Fort on July 24th, in the year 1800, found

many Chippewas encamped near by, living on the sturgeon and white fish

they caught in the lake, and on wild rice, which though darker in colour

than the “real rice,” was nearly as nourishing and palatable. About

1791, Peter Grant, then only in his twenties, but already a partner of

the North-West Company, was in charge of the fort on Rainy Lake, and, at

the request of that literary trader, Roderick Mackenzie, he wrote some

interesting descriptions of the manners and customs of the Indians and

the methods of the voyageurs.

It was Sir George

Simpson, for forty years Governor of the Hudson Bay Company’s vast

territories in North America, who named the Rainy River post Fort

Frances, in honour of his wife, and in his account of his journey round

the world he spoke of this district with less than the usual caution of

the fur-trader when dealing with the resources of the country. “From the

very brink of the river,” he says, “there rises a gentle slope of

greenwood, crowned in many places with a plentiful growth of birch,

poplar, beech, elm, and oak. Is it too much for the eye of philanthropy

to discern, through the vista of futurity, this noble stream,

connecting, as it does, the fertile shores of two spacious lakes, with

crowded steamboats on its bosom and populous towns on its borders?”

In Captain Iluyshe’s

account of the “The Red River Expedition,” he tells with what delight

the toil-worn, ragged troops bound for Manitoba reached Fort Frances,

“the long-expected half-way house.” The fort itself, consisting of "a

collection of one-storied block-houses,” surrounded by a palisade, stood

just opposite to the lovely falls of the Rainy River, and its

surroundings seemed like “a glimpse of the Promised Land,” especially as

the party had been detained for days on an island in Rainy Lake by a

north-westerly gale, solacing themselves as best they could during their

captivity by eating and gathering into every available receptacle the

delicious blue-berries that grew on the island.

Anxious lest the

Chippewas might attempt to prevent the passage of the troops through the

wilds, the Government at Ottawa had sent on agents in advance to inform

the Indians that the soldiers were on the way, and to arrange that they

should allow them to pass peaceably.

A great council had

been held at Fort Frances, and the Indians had lingered there for long,

awaiting the arrival of the force, but the difficulties of the journey

so delayed it that at last most of them grew impatient and left, and,

when Colonel Wolseley arrived, only half a dozen lodges remained pitched

beside the fort. But few as they were, the braves from these lodges did

not permit the colonel and his officers to pass without a lengthy

“pow-wow.” One Indian after another, with his hair plaited in long tails

and his blanket draped about him like a Roman toga, inflicted his

incomprehensible eloquence on the strangers; and the Englishmen, at

first amused with the novelty of the scene, had more than enough of it

before it was over. But the Chippewas gave no trouble; and Colonel

Wolseley established at Fort Frances a depot of supplies and a hospital,

to guard which a company of the 1st Ontario Rifles was left behind in a

camp on the grassy bank of the river. Since those days Fort Frances has

become a busy little place of several thousand inhabitants, having easy

connection by means of the Canadian Northern Railway and steamboats with

the world at large.

Rainy River District

was of course involved in the boundary dispute between Ontario and the

Dominion Governments; but the story can be told more conveniently in

connection with Kenora. |