|

Extracts from Spalding's

Athletic Library (1898)

HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE

Ice hockey is fast becoming a regulation American sport.

Like many others it is an imported pastime and has found almost as much

favor during the past winter as did golf after the first year of its

introduction. Along with the revival of indoor athletics has come an

increased interest in ice hockey, which, dating back but a couple of

years, last winter amounted to that purely American outburst of effort

known as a “boom.” Three winters ago Chicago, Minneapolis and Detroit

were about the only scenes of the game’s activity, but last winter

wherever ice could be found, out of doors or inside, East and West, ice

hockey was being played.

The game should not be confused with hockey nor ice polo.

The former (from which ice hockey and ice polo have grown) is a very

ancient field pastime, sometimes known as bandy, shinney or shintey.

Originally, Romans played the game with a leather ball stuffed with

feathers and a crooked club or bat called a bandy, because of being

bent. A fourteenth century manuscript contains a drawing of two bandy

players facing each other at a short distance and armed with bandy

sticks, very similar to the hockey sticks of the present day used in the

United Kingdom. The object was to strike the ball past each other, and

if one failed to stop it, whatever ground was covered by the ball was

claimed by the opponent, and so on with varying success until either

boundary was reached, the latter being the goal.

The game (hockey) which is now very popular in Great

Britain is played on a rectangular field of turf, 125 yards long by 54

yards wide, with goal posts quite similar to those we use for foot ball.

Fifteen players constitute a team, which consists of a goal-keeper, two

backs, three half-backs, seven forwards and two advance-forwards. They

carry ash sticks 34 inches or less in length, with a crook at the lower

end not more than four inches long, and endeavor to strike a

self-inflating one-ounce india rubber ball (which is 1% inches in

diameter) with the stick, so as to make it pass between the goal posts

and under the cross bar. As may be imagined, the game is exceedingly

rough, probably because so many men are bunched at times. From this

British game Canadians extracted ice hockey and have played the game so

long in their climate, where natural ice skating is indulged in steadily

from Dec. 1st until late in each spring, that they have well nigh

reached perfection.

Only in the most northerly part of the United States are

the winters severe enough to make ice hockey very practicable out of

doors. (Every Canadian town of ordinary size has its covered,

natural-ice rink.) In other parts of our country the lakes and rivers

are seldom frozen hard enough for skating or ice sports for any length

of time, and this has caused a number of artificial-ice rinks to be

constructed in our big cities, where most of the ice hockey matches are

played.

The sport has flourished with both the player and

spectator and will be found interesting to the most exacting critic, his

attention being fully occupied through every moment of play. It has all

the rapidity and great variety of action to be seen in lacrosse and polo

(on horseback) without the roughness of the former or danger of the

latter, and the same opportunity is offered for individual, brilliant

play and perfect team-work (the secret of an ice hockey team’s success).

From the moment the referee signifies the start, the spectators’ nerves

are kept at a tension which is not relaxed until the final call of time,

there being very little or nothing of the element of “time calls,” which

have proved such a fruitful cause for criticism in foot balk

Occasionally a skate may be broken, necessitating a delay of five

minutes, but this occurs rarely; or a player insisting on continued

off-side play or being sent from the ice for infringement of any rule,

causing a momentary stoppage. Otherwise the time is employed in

brilliant rushes, quick checking and clever passes.

The requisites are few—a clear sheet of hard ice,

invigorating atmosphere and a number of quick, sure skaters, who, when

aided and abetted by an enthusiastic company of supporters, will furnish

as interesting an evening’s entertainment as any sport lover could

desire. The principles of the game are so simple as to be readily

understood by even the most disinterested. An ice hockey team is

composed of seven men, four of whom are called forwards or rushers and

form the attack, while the other three, cover-point, point and

goalkeeper, have only defensive work, though at intervals the

cover-point is called upon to back up or feed the forwards. Goal posts

are erected at either end of a rink, shaped like a foot ball or lacrosse

field, which is bounded by upright planking, touching and extending two

or more feet in height from the ice surface. Each player is equipped

with a “stick,” made, preferably of second-growth ash, length to suit

holder, resembling in form somewhat an ice polo stick, except it is not

so curved on the end, which is formed into a blade less than thirteen

inches in length and three in width, and bent so as to rest and allow

about a foot of play along the ice. The object is to drive the “puck”

between and through the opponents' goal posts. The puck is a disk of

solid vulcanized rubber three inches in diameter and one inch thick. It

slides along the ice with great ease and rapidity, being usually

dribbled, and as it passes from player to player it is shoved or scooped

rather than struck at. .

A successful ice hockey player must be very active on his

feet, quick with his hand, keen of eye and have aljl his faculties

alert. He must be an expert on skates, as almost every known skill on

ice is needed in the game, and he should be mounted on regulation ice

hockey skates, the blades of which are almost straight on the bottom and

thus better adapted for the lightning turns and

sudden stops necessary in the play. He must be able to start quickly and

to skate fast and low—as a back must run “hard and low” in foot

ball—thus preventing being easily thrown off his feet by the

body-checking, blocking or interference (all of which is allowed) of an

opponent. He must be able to twist and dodge quickly, as it is often

useful in outwitting an opponent who blocks the path toward the goal.

Ail accomplishment much practiced in Canada, and a very useful one, too,

is jumping over the stick of an opponent while under full headway, and

thus avoiding many a fall or trip, intentional or otherwise. As ice

hockey is a very severe game and one that calls for constant exertion,

on the part of the forwards in particular, players must be athletes of

exceptional endurance and have any amount of grit and “sand.”

Two halves of thirty (sometimes twenty) minutes each

constitute time of play, and the game is in charge of a referee, two

goal umpires and one or two timekeepers.

The play is started by "facing” the puck at the centre of

the field between the sticks of two opposing centre forwards. When the

referee calls “play” these men strive to gain possession of the puck and

pass it to other players of their own team and an exciting attack and

defense of goals follows. Of the four forwards the two best goal-drivers

should hold centre positions and the fastest forwards be placed in the

wings or on the ends. As soon as one of the four gains possession of the

puck he rushes for the goal his team is attacking, the remaining three

following close behind or abreast of him, but spread out across the rink

in an irregular line. Where good form is shown, one forward rarely

carries the puck longer than a few seconds, it being kept on the pass

from one to the other with great speed and accuracy, thus lessening the

opportunity for an opponent to gain its possession. On their way toward

the goal—granted that the opposing forwards have been passed— the

opposing cover-point is the first man encountered and he, of course,

confronts the player with the puck. The latter passes it across to one

of his partners and thus they advance until the point is reached, where

perhaps another pass is necessary and, if

successful, the goal is attacked. A number of quick shots and stops

follow until a goal is either scored, or an opponent “lifts” the puck

down the rink and out of harm’s way, or possibly dribbles it down,

followed by his own forwards and thus forms the attacking party on the

other goal.

The sides of the rink are used somewhat like billiard

cushions, and in making a run, a player will, after having used his

ability in dodging his opponents, carrom the puck past an opponent, or

to another of his own side who has signaled and is ready to receive it.

While running with the puck it should be dribbled just ahead of the

player; that is, advanced by a rapid succession of short, alternate

right and left strokes, thus baffling an attacking opponent.

The main object of an expert player, and very difficult

of accomplishment, is to “lift” the puck, making it travel over the

heads of his opponents a distance of twenty or thirty yards perhaps when

necessary before striking the ice. It is the duty of the point and

cover-point to “lift” whenever necessary to keep the puck in the

vicinity of the opposition goal. These two players are “feeders” for

their forwards, and they should “run” down with the puck when they have

fairly clear ice, rather than losing possession of it by lifting. This

stroke is also invaluable to a player when shooting for goal, as a goal

keeper can almost always stop the puck when shot from any distance if it

slides along the ice with his skates or stick, but they are of little

use in preventing a sizzling, “lifted” shot from scoring which comes at

the goal about two feet from the ice. To “lift” a puck, an indescribable

wrist motion or twist is imparted to the stroke, which employs a full

arm and body motion-to give it force, and it can only be gained by long

practice. An expert can “lift” a puck through the air with the greatest

accuracy and terrific speed. Of course, both hands are used to handle

the stick—this being an unwritten law of ice hockey—and a player need

never expect to do any effective work without both hands on his stick

at any stage of the play. A player who attempts to advance or even

control a puck with but one hand on his stick, and the latter probably

at arms length, is easily disposed of by an adversary, who can readily

push the one-hander’s stick away by the slightest blow, whereas, if

properly held, a much greater degree of force can be withstood, and the

control is strengthened beyond measure.

The “off-side” rule in ice hockey is the controlling

feature of the game, adding to the play great interest and complete

government of attacking methods. The rule provides that a player shall

always be on his own side of the puck or simply speaking, its object is

to prevent a player passing the puck forward to another member of his

own team, but admits of his passing it across the rink at right angles

to the side lines, or back toward his own goal. A player is “off-side”

if he is nearer the opponent’s goal line than the player of his own team

who last hit the puck, and he is not allowed to touch it, or interfere

or obstruct an opponent until again “on-side.” He may be put “on-side”

when the puck has been touched by an opponent, or when he has skated

back of one of his own side who either has possession of the puck or

played it last when behind the offender. A match is stopped if a man,

when off-side, plays the puck or obstructs an opponent, and as a penalty

the puck is faced where it was last played from before the infringement

occurred.

This rule tends to make the player in possession of the

puck keep even with or a trifle ahead of his other forwards at all

times, thus allowing him to pass it to any of them whenever his progress

may be threatened or obstructed; were they ahead of him he would be

without allies.

The puck may only be advanced by the use of the stick,

but it may be stopped by the skate or any part of the body (the Ontario.

Hockey Association rules prevent stopping the puck with the hand except

by the goal-tend). Thus a clever goal-tend intercepts many a

try-for-goal, though at the cost of as many bruises where his body has

met the flying puck. He very rarely leaves his station between the

goal-posts, and then only after signaling the point to fall back into

his position, the goal-tend having left same in order to return a long

“lift” which has dropped back of and near the posts, the opposing

forwards, of course, being at some distance down the rink.

Through the agility of a clever goal-tend the score of a

match is often kept down to a small number of goals, as he kills many

tries which would score but for his good work. The rules forbid him to

lie, sit or kneel upon the ice, and compel him to maintain a standing

position. When a scrimmage occurs near his goal, his is the most

difficult, and usually the most thankless, work of any man on the team.

Though he may frequently gain a momentary possession of the puck, he

seldom has room or time to pass it far down the rink or even directly to

one of his own side. His play then is to shoot it off to one side of the

rink, either to the right or left of the ‘goal, thus preventing another

try-for-goal until the puck is worked back again into a favorable

position.

The thorough or loose work of a referee regulates the

amount of foul play in ice hockey, and unless he be firm and strict, for

players so inclined, there are many opportunities to trip, collar, kick,

push, cross-check, charge from behind, etc., all of which are forbidden

by the rules. For infringements of this character, as well as for

raising a stick above the shoulder, the penalty is disqualification, the

referee ruling the offending player off the ice, for any portion of

actual playing time as he may deem fit.

Goal umpiring is by no means the least important part of

an ice hockey match, though the manner in which this office was filled

at many league contests in New York City last winter would lead one so

to believe. As a decision made by a goal umpire is final, he should be

most painstaking and always on the alert. His work can only be performed

properly when stationed in a cleared space reserved solely for his use.

This space should be just back of the rink boundary and somewhat longer

than the goal is wide, as he must be able to move instantly in order to

get a true line on shots for goal made at many different angles. Many a

match has been won for a team by the tricky work of their goal tend, who

by a quick stroke has put the puck in play again after having stopped it

several inches in goal, this being done of course when a “slow” umpire

was “taking things easy” in a chair directly behind the goal-tend’s

back, or caught standing in a similar position.

To Yale University belongs the credit for the importation

of ice hockey into the States, or more correctly, to the efforts of

Malcolm G. Chace and Arthur E. Foote, of Yale. These men, who are both

lawn tennis experts, learned of the popularity and fascination of ice

hockey while on one of their visits to Canadian tennis tournaments, and

both became confirmed devotees of the sport at first sight. The

following winter (about 1894) this pair organized a team of Yale

skaters, most of whom were tennis cracks, and during the Christmas

holidays a tour of the prominent Canadian rinks was made.

Of course the American players (who had previously

practiced with only a rubber ball instead of a puck) were sadly defeated

in all the matches they undertook, but the trip was regarded as a

success, as it furnished much excellent sport, the best sort of

instruction, and created no end of enthusiasm in the breasts of the

visitors. They all praised the game highly upon their return, and went

at it with renewed vigor each season, and from this introduction it has

rapidly spread to its present popularity.

CANADIAN ICE HOCKEY

Throughout Canada ice hockey is as common as base ball in

the States. Nearly every town, social club, college and school has its

representative team, and many banks and business houses are represented

as well. Dozens of leagues have been organized for years, and each

winter they promote series of competitions which keep the sport booming.

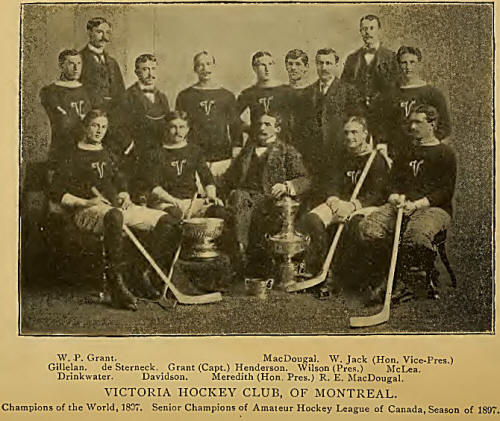

Many towns and cities in Canada have a “Victoria” hockey

club, the name being so commonly popular and adopted by so many

different clubs that it is necessary to mention their locality in order

to distinguish one from the other.

The larger leagues and associations offer trophies for

competition to junior and intermediate teams as well as to the senior

teams representing the clubs or organizations composing the body. This

is done to develop the young players, and the scheme works to

perfection. No club is allowed to compete for the senior championship

until it has won the intermediate championship, and likewise a club must

first win the junior series before being eligible to compete with the

intermediates. Also, no man may play in the intermediate series who has

taken part in more than one senior match in the same season, and no man

is eligible to play in the junior series who has played in more than one

intermediate match or in any senior match during the same season.

AMATEUR HOCKEY ASSOCIATION OF CANADA

The most prominent league in existence is the Amateur

Hockey Association of Canada, composed of these clubs: Victoria Hockey

Club of Montreal, Ottawa Hockey Club, Montreal Hockey Club, Quebec

Hockey Club and Shamrock Hockey Club of Montreal.

The Montreal Hockey Club won the championship of the

Amateur Hockey Association of Canada in 1888, and held it for eight

consecutive years, when the Victoria Club wrested the coveted title from

them.

The Victoria of Montreal are the present champions of

their association, and also hold the Stanley Cup, emblematic of the ice

hockey championship of the world. The clubs of this Association play a

series of home matches between January 1st and March 8th of each year,

the winner of the most matches being declared the champions. |