|

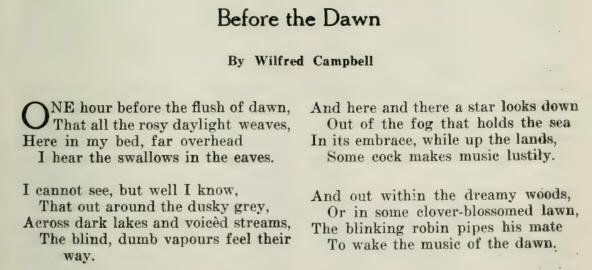

IN the year 1888 there

was published in St. John, N.B., a little book of verse entitled

Snowflakes and Sunbeams, by William Wilfred Campbell. Campbell was at

that time rector of Trinity Church, St. Stephen, N.B., and the book was

published as a means of raising money for charity. It was a slight

paper-bound volume, containing only some twenty short poems; but among

them were a number of exquisite lyrics, notably the poems entitled Snow,

Indian Summer, and Before the Dawn. Most of these lyrics had, however,

already appeared in magazines, and their publication now in book form is

important only because it definitely marks the beginning of Campbell’s

career as a poet.

Campbell’s father and grandfather were clergymen; and at the time of the

poet’s birth (1861) his father, Rev. Thomas Campbell, was rector of the

Anglican church at Berlin (Kitchener,) Ont. Wilfred Campbell was the

second son in a family of seven boys. For a number of years after the

poet’s birth the Rev. Thomas Campbell did parish work in the eastern

part of Ontario, in Lansdowne, Athens, and on the upper Ottawa; but in

1871 he removed to Wiarton, on a branch of the Georgian Bay. From this

time forth, Wiarton was the family home, and the scenery and

surroundings of this romantic neighborhood had much to do with

stimulating the poet’s imagination. He attended High School in Owen

Sound, after which he was engaged in teaching for two years. At the age

of twenty he entered the University of Toronto, with the intention of

taking the first two years in one. But after one year in Arts he decided

to study theology, and next autumn (1882), he was registered as a

student in Wycliffe College. Those who knew him at this time report that

he was not interested greatly in student life or in sports; but, as in

later life, he was fond of discussion and argument.

After a year at Wycliffe he attended the Episcopal Theological School in

Cambridge, Mass., as a special student. In the meantime in 1884 he was

married to Miss Mary Dibble, daughter of Dr. Dibble, of Wood-stock, Ont.

Marriage, while he was still a student and with limited means of

support, may seem to have been imprudent; but in his case it proved a

steadying influence.

The following year (1885) Campbell was ordained as minister of the Union

Church at West Claremont, New Hampshire; and during the three years that

he remained there he began to contribute poems to The Atlantic Monthly

and Harper’s. Tn the year 1888 he resigned his charge at West Claremont

to become rector of Trinity Church, St. Stephen, N.B. The two years that

he spent here were years of happy inspiration and earnest work. The

little volume Snowflakes and Sunbeams, it is true, attracted little

attention; but in the following year (1889), other poems were added and

the larger collection appeared under the new title of Lake Lyrics. It

was this little volume that first gave Campbell a recognized place among

Canadian poets. Most of the poems contained in the volume are true “lake

lyrics,” descriptive of the scenes and impressions of the poet’s boyhood

and youth. They are an at-1 tempt to express in language something of

the glamour of this “magic region of blue waters,” the “wild paradise”

of the northern lakes, which had made a lasting impression on the poet’s

imagination. He knew and loved the lake country in all its moods, from

the sunlight on the blue water which lay stretched out beneath the

hilltop where stood his boyhood home, to the harder and harsher prospect

of the ice-bound bay on which he skated as a boy. It was all an

inspiration, and we can understand why he chose as a title to one of his

later books in prose, The Beauty, History, Romance and Mystery of the

Canadian Lake Region. To him, as boy and man, it was a land of magic.

But aside from the lake lyrics, there were a number of poems in the

volume which showed that Campbell possessed gifts other than those of

the merely descriptive poet. In Dan’l and Mat and in Lazarus, there

appeared in two widely diverse forms unmistakable evidence of unusual

narrative and dramatic power. There are two songs of childhood which are

written in a tender, affectionate, delicate vein; and in the last poem

in the series, the sonnet on Knowledge, it is the soul of the

philosophic, didactic Campbell that looks out upon the mystery of the

world.

In 1890 Campbell resigned his charge in St. Stephen, and after spending

a few months in Southampton—a short distance from his boyhood home in

Wiarton—in charge of the parish, he withdrew from the ministry. He

perhaps felt that the creeds of the church were too narrow and dogmatic,

and he was too independent to hold to dogmas with whose spirit he was

not fully in accord.

It was not long,

however, before he found more congenial employment. In the following

spring he was appointed by Sir John Macdonald to a position in the Civil

Service at Ottawa—the very last appointment which the veteran chieftain

made. In this position his duties were light, and he had a good deal of

leisure time for reading and study. His life, from this time forward,

except for the publication of his books, was, on the whole, uneventful.

In 1893 he was elected

Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, and thereafter he took a great

interest in the work of the History and English Literature Section of

the Society. In 1906, on the occasion of a visit to Scotland, he was

asked to represent the Society at the four hundredth anniversary of the

founding of the University of Aberdeen; and on that occasion, along with

some eighty others (including Andrew Carnegie and Signor Marconi), he

received the degree of LL.D., and during the ceremonies he was presented

to the King and Queen.

But his real life and real interests during these years lay in his

literary work. Two years after his removal to Ottawa he published The

Dread Voyage and Other Poems (1893), and this was followed a few years

later (1899) by the volume entitled Beyond the Hills of Dream. In these

two volumes a distinct change comes over his work. There is a widened

range of interest and a deepening of tone. He is now not so much

interested in nature for its own sake as for its human associations; and

myth and legend occupy a larger place in his poems. Among the finest of

the poems in these two volumes are The Mother, the poem by which he is

best known; the dramatic monologue Fnabsolved, the exquisite Harvest

Slumber Song, and The Bereavement of the Fields, written upon the death

of Lampman.

His Collected Poems, published in 1905, in-eludes more than one hund:

red hitherto un-published poems; and this new volume contains the best

of Campbell’s mature work. Perhaps in some poems the phil-o s o p h e r

and teacher, the preacher of human life, is too much in evidence, and

perhaps, on the whole, there is a sacrifice of the sensuous elements,

the pure music of his earlier verse, to philosophic utterance; but poems

such as Lines on a Skeleton, The Hills and the Sea, The Vanguard, The

Dream Divine, A Canadian Galahad (Henry A. Harper), Not Unto Endless

Death, and the lines on Poetry are examples of Campbell’s finest and

most enduring work.

Campbell had a strong dramatic sense and an ambition to write great

dramas that might be acted on the stage. In 1895 he published two

dramas,, in a volume entitled Mordred and Hildebrand. In 1898 two others

were added, and he has left several other dramas which are still in

manuscript form. At a later period he became interested in prose

fiction, and produced two historical novels, Ian of the Orcades (1906)

and A Beautiful Rebel (1909). But neither , his dramas nor his novels

can take rank with his poems, and it is on his work as a lyrical and

reflective, poet that his reputation must finally rest.

During the last ten years of his life Campbell became more and more

interested in world politics, and his later poems are strongly patriotic

and imperialistic in character. In these later years, indeed, so changed

was his point of view that he even spoke slightingly of his own earlier

nature poems, When the Great War broke out his patriotic spirit was

stirred to the depths, and pride of race and passion for British

tradition found? expression in a number of stirring war poems, some of

which were not published until after his death. But admirable though

they are these poems of race and empire have in them less of “the dream

divine” than his earlier work.

It is not surprising that the general reader finds it difficult to form

a proper estimate of Campbell’s work; fOr his poems are diverse in theme

and treatment and uneven in character. In general, there were three main

influences that affected the character of his poetry. Perhaps the

strongest of these was his Celtic temperament. He traced his descent

from the Campbells of Argyll, and he was very proud of his lineage.

Throughout his life, indeed, he was an intimate friend of the late Duke,

who is better known to Canadians as the Marquis of Lorne. This Celtic

strain—its fire, its impetuous ardour, its seriousness, its dignity, its

tenderness, its sense of mystery, is in evidence in much of Campbell’s

poetry. And nearer at hand there is the inheritance from his immediate

ancestry. His father and his father’s father were churchmen, and he

himself had been associated with the Church for nearly ten years. This

may account, in part at least, for the tone of seriousness sometimes

approaching austerity, the spirit of moral earnestness, that pervades so

much of his work. It was from his mother, however, that he inherited his

purely literary gifts, his love of music and painting and good books,

and his sense of literary style. The third great influence, which

supplied the inspiration for his earlier verse, was “the beauty and

mystery” of the northern lake region. It held Campbell under its spell

as another part of the north country held Tom Thomson at a later day.

As a result of these diverse influences Campbell excelled in various

forms of poetry—in the pure nature lyricj in narrative and dramatic

poetry, in philosophic and reflective verse, and in lyrics which appeal

to the emotions and stir the imagination of the reader. He takes rank

easily as one of our greatest Canadian poets, and at times he rises to

heights which place his work on a level with the classics of the greater

British poets. But for various reasons his work was not fully

appreciated in his lifetime, either by the general reader or the

literary critic. The average reader of poetry was no doubt repelled by

the didactic tone of much of his verse. Then, too, the work of Campbell

is uneven in quality. There are poems that are dull and even harsh in

tone. Campbell evidently did his finest work when his Celtic imagination

was stirred by strong emotion and in those supreme moments he was, in a

sense, inspired; but he spent little time in perfecting the technical

form of his verse. In his later period he came to attach so much

importance to the thought and so little to poetic form that his poetry

suffers as a result. But in his moods of poetic exaltation his verse

rises to heights of rare poetic beauty.

But perhaps the main causes— weaknesses you may call them if you

will—that were responsible for the general lack of appreciation of

Campbell’s poetry were his own personal peculiarities of temperament. He

had strong likes and dislikes, strong aversions and strong convictions;

he was tenacious of his opinions and inclined to be intolerant of those

who held different views. Moreover, he felt very keenly the fact that

his work was undervalued by the public, and he accordingly put an

estimate on his own work which gave him the reputation of being

egotistic. But if Campbell was egotistic, so was Wordsworth and so was

Tennyson, in his later years at least, and so were many other great

poets.

Aside from idiosyncrasies such as these, Campbell’s personal tastes and

habits of life were not such as to bring him into public notice. His

tastes were simple, he belonged to no clubs, and preferred his own

fireside, with music and poetry and discussion with intimate friends,

quiet walks in the country, correspondence, and the companionship of

books, “letting the world remote, and its roar, go by.” Some years

before his death he removed to a suburban home—Kilmorie house, on the

Merivale road—high above the Ottawa Valley, and with a view of the

distant Laurentians; and here he spent much time in gardening and in the

improvement of the grounds of his new home.

In personal and public life he was actuated by the loftiest motives. The

following passages from a letter which the writer received from him some

years before his death is an admirable expression of his ideals: “Canada

wants today to be saved from her worser-self, namely materialism. The

best cure is in the highest British ideals—character, culture, loyalty

and imagination. The people want to forget their ‘rights’ and awake to

their ‘responsibilities.’ For this end we must all work—both the

educationalist and the poet, side by side.”

At the time of his death he had scarcely passed the prime of life, but

perhaps he had outlived the period of his highest poetic powers. He died

very suddenly, of pneumonia, on New Year’s day, 1918. He was buried in

Beechwood cemetery, in a plot of ground overlooking the Gatineau Valley,

with the blue Laurentians on the far horizon. The plot was the gift of

Hon. Mackenzie King, one of his most intimate friends. The monument, a

seat in marble, was a token of affection from other friends and the

medallion in the centre was the tribute of Dr. Tait Mackenzie, the

eminent sculptor, an old personal friend.

Check-List of First Editions

Snowflakes and Sunbeams, St. John, NJB., 1888.

Lake Lyrics, St. John, N.B., 1889.

The Dread Voyage, and Other Poems, Toronto, 1893.

Mordred and Hildebrand, Ottawa, 1895.

Beyond the Hills of Dream, Boston and New York, 1899.

Collected Poems, Toronto, 1905.

Ian of the Orcades, a Scottish 'Romance, Edinburgh and London, 1906.

Canada (illustrated by T. Mower Martin, R.C.A.) London, 1907.

Poetical Tragedies, Toronto, 1908.

A Beautiful Rebel, an historical novel, Toronto, 1909.

The Beauty, History, Romance and Mystery of the Canadian Lake Region.

Toronto, 1910.

The Scotsman in Canada, Toronto, 1911.

Sagas of Vaster Britain, London, 1914.

Poetical Works, London and Toronto, 1922.

Editor, Oxford Book of Canadian Verse, London: 1914.

The poetical works

of Wilfred Campbell

Edited with a Memoir by W. J. Sykes (1922) (pdf) |