IT is the proud boast

of the people of Pierreville on the St. Francois river, on the south

side of the St. Lawrence, that there is no bridge other than the

railroad bridges over any river between Pierreville and Montreal, and

that if you desire to cross any of these rivers you must do so on the

picturesque ferry-scow which m'sieu the ferryman, guides over the calm

water, mirroring reflections on every hand, on a wire-cable cleverly

seized by him in the snapping jaw of a sort of a wooden monkey-wrench.

We "called the ferry"

at this Twickenham of Canada for the first time in August and set up

house-keeping in a cottage on the main street of the village of Odanak

just at the point where the street comes out on the high bank

overlooking the river St. Francois. So that to watch the upper ferry

from our front porch became a daily amusement.

Pierreville and Odanak

adjoin each other but enjoy separate post-offices. Pierreville is the

French-Canadian town and Odanak the village of the Abenakis. Our "maison"

was a sort of boundary line, I believe. Odanak when translated, we were

told by the Episcopal clergyman, means "Our Village", so what with the

picturesque ferry and literary suggestions of Miss Mitford in "Our

Village" name, our August camping-ground became atmospheric at once.

But wherever there are

Indians they take the centre of the stage and hold it. Odanak is "Our

Village" to the Abenakis. And as far as I know it is the only

home-village in the possession of what is left of these people.

The Abenakis were the

"original Yankees". They came to the banks of the St. Francois from

Maine, Vermont and Massachusetts. If you wish to know more about their

interesting past read "Uistoire d'Abenakis, depitis 1605 jusqu'a nos

jotim, par L'Abbe J. A. MaurauU". It is a thick volume and makes a

pleasant tale to read by a roaring fireside of a winter evening. But

this present sketch deals with the living present—the Abenakis of "our

day" from the human interest angle.

Just as the Hurons of

Lorette are snowshoe, canoe and moccasin-makers, the Abenakis are

sweet-grass basket-makers. And their market? Mais oui—all over

Canada—east and west—, north and south, and the United States. Rumour

says that the turnover to the village and region from the baskets is in

the neighbourhood of $250,000 a year. Men, women and children work at

this basket industry. There is no factory. It is all pleasant homework.

Women at work sit on their porches. Housewives ply their fingers in the

kitchen, picking up the basket, as other women pick up knitting. Little

children braid the grass over backs of chairs in the door of the little

play-tent on the lawn. Schoolgirls make pin-money at it. Neighbours

gossip in dooryards, basket in hand.

Baskets talk in the

grocery and dry-goods shops in Pierreville as successfully as money. If

a man or a woman needs a little change, he or she takes a basket in hand

and comes back with the silver. It was a happy discovery when the

founders of this people trekking it to Canada came by chance on the

original grass growing on islands in the river. It was a still luckier

turn of fate that prompted some old squaw to dry it as a simple herb and

in so doing—though she must have been disappointed from the herbal point

of view—to learn the astounding fact that dried, the grass gave forth a

pleasing odour—that it was —in her simple language—"sweet".

So simple a discovery

as this, and determination to put it to use, is the Abenaki's

stock-in-trade. Out of it he has built up a quarter-of-a-million dollar

business. And he now farms the grass as do more or less all the French

farmers of this neighbourhood, because the business has grown to such an

extent that the natural supply is not enough. The only part of the

basket taken in hand by the men is the preparation of the splint from

the big log. The only factory (?) for this work stood across the street

from out-door. It was merely a neat yard with a board top for shade.

Here every morning two big ash logs were pounded with the head of a

wood-axe until the layers or rings of the tree's growth could be

stripped off. Little by little these strips were made thinner by a man

who separated the ends of each strip and tore them asunder, through

their entire length, by means of two small boards held between his

knees.

Other men ran the

strips through a planing machine. Two keen steel teeth in a board,

paralleled the required width, and the wooden ribbon rolled into a bolt

was ready for both the market and the dye-pot of madame. I should not be

surprised if this is the only factory of its kind on this continent.

Certainly it is the only one with Abenaki labour—and Abenaki atmosphere

throughout. Its counterpart has been here a long time. Its beginnings

reach back very far into Canadian history.

Visiting the dyer,

madame, swishing her ribbons into her pots of boiling dyes and out again

even as you watch, speaks with regret, and if she is an old-timer, with

genuine sorrow, at the passing of the old homemade dye of which her

Indian forbears knew so well the secret. "Those dyes", she says in her

soft English voice full of the plaintive tones of the red man, and rich

with memories of the past, "those dyes were beautiful! and, oh, we could

get such lovely colours with them! Oh, but now we couldn't make the

dyes. It would take too much, and so we use the store dyes. And of

course we are very glad to get them. But the old colours were lovely."

And in dreams, you can

see, she still beholds the pinks and blues of other days. And herein

lies what for her is the tragedy of the larger trade.

However, the younger

woman snapping the ribbons into splint-lengths with her sharp scissors

has no regrets. She holds up for inspection the spokes of the

bottom-wheel. "Six colours, madame," says she—"yellow, purple, vivid

green, light blue, red and then pink."

But the wheel turning

in her hand like the wheel of fortune, brings us around to the grass

again without which there can be no basket. The grass is a story in many

chapters spreading out to the countryside and, crossing the river,

trailing its way through St. Francois du Lac, the large town facing

Pierreville, out to the French farms bordering the high-road to popular

Abenaki Springs, where summer visitors go "to drink the waters" and idle

away the summer days.

The grass is grown in a

bed. When grown it stands up in long wisps two to three feet high.

Pulled while still green, girls of the farm-family clean it of decaying

leaves but do not bother to clip any clinging roots because these hold

the plant together better for the braiding. Apparently it is wilted or

dried only a few days when the "tresseuse" takes it in hand. All down

both sides of the river thousands of miles of this grass-braid is turned

out. Winter and summer the braiding goes on. We saw them braiding away

in August—the same hands are braiding to-night. Abenaki fingers learned

the A.B.C. of it in 1685 when they erected their wigwams on the east

bank of the river and here in the year 1922 they are still—braiding.

The "braid", of later

years, has grown to be a business in itself. French farm-families of the

neighborhood often grow the grass and braid it. Then they make it up in

hanks or echeveaux, and retail it to the basket-weavers in Pierreville

and Odanak. An Abenaki who can make more baskets than she can grow grass

for, is very glad to invest a little capital in the hanks, as she also

invests in the rolls of wooden ribbon from the factory.

The Abenakis, despite

all the work being done in the homes, are a very neat people. They are

nearly all well-to-do. Even if they do put all their dependence in

one—basket! So far it has proved a very safe investment yielding a high

rate of interest. They mostly all own splendid little homes, some quite

fine houses in spacious grounds.

"Our village" is as

sweet a village as old Quebec affords anywhere! Its main street is

shaded by tall and stately old trees. In the centre of the village and

situated in a grove on the high bank overlooking the river is their fine

church, a simple yet dignified and peaceful little place of worship.

Father de Gonzaque, the

cure, is himself of Abenaki descent and a most genial man. Calling on

him one Sunday morning after Mass, the Grand Chief happened to drop in

and between them they kept the Abenaki ball rolling to our enlightenment

for upwards of an hour.

Father de Gonzaque is

not only of Abenaki descent but he has been priest here twenty-five

years. And this is the Grand Chief Nicholas Panadi's third time of

office, so we were indeed for- tunate that Sunday morning.

Among other things we

learned that the present church is the fourth on this site. The first

was a wooden one built in 1700, and was burned in 1759 by British

troops, the Abenakis having espoused the cause of France—and lost in the

game for half a continent. But the Abenakis were good churchmen. They

built second church the following year, in 1760, this held the riverbank

and the tribe until 1818, when it was accidentally burned. Then for ten

years they had no church, and Mass was said in the council room. In 1828

the third was built and this in 1900 was struck by lightning and burned

to the ground, and since that time the present edifice has been erected,

so that in a double sense this is Father de Gonzaque's church—for he

built it.

An interesting tablet

occupies a conspicuous place in the wall on the left-hand side facing

the altar, and reads thus:

HONOUR,

To the Honourable Mathieu Stanley Quay, Senator of

Pennsylvania, U.S.A., of Abenaki descent.

"He made glad with his works

And his memory is blessed forever."

A.D. 1902.

In the grounds of the

church, in addition to the parish priest's house, the sisters have a

large school for the Abenaki children, and there is also a neat

graveyard, and the Grand Chief's house borders upon a little lane

bounding the church property. In front of the church on a bank

overhanging the river is a large summer house apparently for the

convenience and pleasure of Abenakis awaiting the church service. It is

remarkable for its rusticity, all the work being the handiwork of

Indians. And this in addition to commanding a superb view up and down

the river made it an interesting rendezvous for us of an August

afternoon. Not all the Abenakis are Catholic, however, as is testified

by the little brick church—also beautifully situated in a grove of trees

on the riverside—of the Church of England. The church is of historic

interest in that Queen Victoria herself gave the sum of fifty pounds

towards the building of it. It dates back to 1866.

There is also a Church

of England school, and there they teach both Abenaki and English. So

that all in all the Abenaki children are well taught, and all claim that

the Abenakis are very intelligent and quick to learn.

When the United States

Government sent an observer to Canada some years ago from the Indian

Department in Washington to see what could be learned from Canada as to

the government of the Indians, the Abenaki at Pierreville was one of the

tribes and villages visited. The visitor went back enthusiastic. He

wrote pages about them in his report which began: "In the beautiful

little village of Pierreville".

And this report was

certainly borne out by all that we saw of the Indians there. Like the

Hurons they have intermarried very much with the French, so that there

are very few full-blooded Indians now living. One of the purest is now

an old man of eighty. He lives a little way out of town and spends the

evening of his life in comfort though not in idleness. For he is the

toy-canoe maker of the tribe. He specializes in little birch-bark canoes

about a foot long.

Whenever I see, no

matter where, one of these little craft exhibited for sale, it carries

me swiftly back to the morning we came on old Joseph Paul sitting at his

bench in the shade of a big tree in his dooryard. The old man is a

little deaf but his pins and tools were all laid out so neatly!

Everything—twine and strips—just where he could put his fingers on it

with the least loss of time. It was inspiring just to watch him building

the little boat in hand. I had always had an idea somehow that it was

squaws who built the canoes till I saw this old man at work. Is it ten

dozen canoes a week he makes?

As I hold one of these

little canoes in my hand what does it not symbolize?

It symbolizes for one

thing the voyagings of this people. Even now, although they have homes

here, the Abenakis are still voyageurs. In the summer the men go off as

guides to the sports- men from the "Clubs". The reedy places of the wild

duck's nest, the best pools for trout, the haunts of deer and bear and

other wild creatures are familiar chapters in their nature book. Those

who are not guides turn a penny by tripping it every summer to

fashionable resorts of the Adirondacks with their baskets and canoes.

But chiefly baskets! The sweet-grass baskets are made in many shapes.

One company especially, one of the largest wholesale dealers in Indian

wares in Canada or the United States, shows a sample book with many

patterns and each pattern done in several different sizes. Some are all

green and others in colour. The basket-makers have the trade at their

finger tips. Never at a loss, they can make anything which can be made

with grass. The very old women are expert napkin-ring makers, which is

their specialty.

One old woman sits in

her garden on the hill-climbing road from the traverse, as the French

call the ferry, and weaves her rings that are to grace the dinner-tables

of the east and west. She invites us, in her frank manner, to sit down,

seeing perhaps in the summer visitor a possible customer. But no, she

does not sell retail. "They are all engaged, madame," she remarks

modestly. Then she adds, "but maybe, I think, perhaps you like to look?"

So we take the chair

madame offers, and a neighbor comes out and leans over the garden gate

and we chat, and on the calm river le trarersier ferries the flat-boat

to and fro and his passengers in their strange heterogeneous ensemble

present a passing show that carries one out on imaginary roads that lead

back to the age when romance was in flower here and Louis Crevier was le

Grand Seigneur over all this fair demesne.

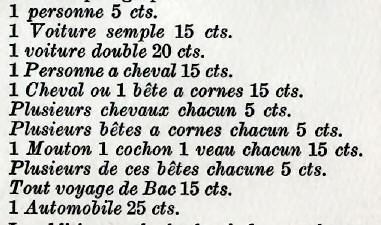

That one may have some

idea of the passengers who traverse the St. Francois at Pierreville the

following comprehensive avis or public notice at the landing-place will

tell more in its quaint way than a dozen paragraphs:

In addition to the

basket-industry, the men at the factory by our door, make rustic

porch-furniture out of their ribbons of white ash. They paint the frames

of the chairs that bright art-red which gives our porches such an air of

welcome on a warm summer day.

Seldom a train goes out

to Montreal—and there is just one a day—but carries crate upon crate of

baskets and shipment upon shipment of this handmade furniture. When you

come to think of it $250,000 worth of sweet grass baskets spells a great

many baskets. It spells application and swift industrious fingers. It

spells good homes and comfort for the three hundred Abenakis living in

"the beautiful little village of Pierreville", and it spells a dainty

sweet-grass basket for many homes in Canada and the United States.