|

I left Paddington by the Canadian Northern Special for

Bristol, on an afternoon towards the end of July, 1911. There was, of

course, the usual bustle and confusion pertaining to these specials;

heavy vans of postal bags, and piles of luggage, threatening to fall

upon and overwhelm the scurrying crowd of passenger, who, like myself,

were no doubt looking forward with pleasure to being on the water, met

ting the cool sea breeze, and leaving the great heat of 94" in the shade

behind in London On arrival at Avonmouth we at once went on board; there

were over eleven hundred passengers all told. The dock strike had not

yet been settled, and several of the firemen were clamouring to get

ashore again; but as they had “signed on," their desertion would have

been a criminal offence, and the police kept them from going with their

kitbags down the gangway. They looked very determined, and one or two

seemed rather as it they had been coerced into leaving, but they were

all kept on board except three, who left by the pilot boat later in the

evening.

At last, the mails were all aboard, the last farewells

waved from friends on shore, and we cast off, steaming very slowly out

of dock.

All was bustle for awhile, every one getting his bearings

about the ship. The hand baggage, as well as the heavier luggage, had

been carefully labelled with different coloured labels for first,

second, and third class, number of cabin, number of berth, and a special

label bearing a large initial of the surname of the passenger, so that

all one's belongings for cabin use were conveyed by stewards on the boat

to their proper place without confusion or delay.

Fortunately I had been given a berth in a first-class

state-room which was a deck higher up than the second, and where it was

not so intolerably hot as on the lower deck.

After a good dinner, I at once betook myself on deck to

get a little accustomed to my surroundings, and to see the last, for

awhile, of old England. It was so hot that I remained on deck until

night came, and we could only distinguish the towns by their lights,

and. when we had passed Ilfracombe, I turned in.

The state-room and the passages leading to it were very

hot, my room being an inside one. I will here describe, as well as I

can, the arrangements and positions of the cabins. They reminded me

somewhat of the formation of the bookcases in the Bodleian Library at

Oxford, which are built in blocks, dissected by seemingly interminable

narrow passages. In something the same way were the cabins arranged.

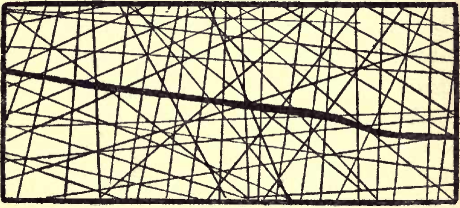

Imagine long narrow passages lengthways through the

vessel, the inner sides being used principally for the staff; the outer

side, consisting of blocks of four cabins, forming a square with a short

passage between each block; thus two of each block of four must

necessarily be inside cabins without a porthole; for example:

so that the inside cabins have practically no air, and

only artificial light. We had two fixed lights and one movable one, to

the latter of which could be attached a fan. The cabins are most

luxuriously fitted, and were, I should judge, about seven feet by eight,

each cabin accommodating three passengers, two berths being on one side

and a couch on the other. A wardrobe (hanging), with a oval-glass door,

and a deep drawer at the bottom, was placed at the, foot of the berths,

and a second one at the foot of the couch, and opposite the entrance to

the cabin was a mock chest of drawers, which, when pulled out or let

down, contained every possible toilet requisite. The bunks were made

with wire springs under the hair mattresses, and were fitted with sweet

little cream curtains with a quaint design in pale green and pink, to

draw along your bunk at wall Towels were never left to be used a second

time and the cabins were kept delightfully fresh and clean; the walls

were enamelled white, and the furniture, I think, was of mahogany with

silver plated mountings.

The boat having its full complement of passengers, we

were three in the cabin, the sofa having to be used for a berth, but by

arranging amongst ourselves that we would not all dress at the same

time, we managed very comfortably, and it will be a very long time

before I forget the delightful times we had in that cabin.

My two companions were a merry couple, one, who was, I

should think, nearing middle age, was going out to Peterborough to be

married; the second was a young schoolmistress, a very bright and

refined girl of about twenty-two, going out on the advice of, and with,

some friends she had accidentally met at home; that she should be going

at all seemed rather pathetic, as she was the only child of a widowed

mother for whom my heart sometimes ached when thoughts of her, without

her girl, left by herself in the homeland, crossed my mind.

In spite of everything being new and strange I slept

fairly well; though the ship was ploughing through the water at a great

rate, the movement was scarcely perceptible, and, on waking up I had to

wait, breathless for a second or two, to be sure that we were moving at

all.

In the morning I was more surprised than I can say, to

find that I had the dreaded mal de tier, as also had my two companions,

and we were altogether a sad trio. We could not account for this

sickness in any way; I have been many short, rough sea passages—across

the North Sea to Norway, round the coast of Scotland from Leith to

Liverpool, from London to Edinburgh, across the Bay of Biscay, and have

had many stormy journeys across the Irish to and English Channels, but

have never even felt ill, whilst here, with the sea like the proverbial

mill pond, we were, all three, too ill to dress. Later in the day two of

us crawled up on deck, but I could not take any kind of food, nor even a

sip of tea or water, for forty-eight hours.

How I bemoaned the utter loss of two whole days’

enjoyment of my ocean journey! I did not like this enforced rest—it was

not at all the kind of rest that I sought. The attendance in our cabin

was everything we could desire; the stewardess and the bedroom steward

vied with each other in their kind ministrations; the latter was quite a

humorist, threatening all kinds of penalties if we did not rise, and yet

kindness itself in getting and doing everything possible for our

comfort. We named him the “fairy” as he was always popping in and out,

to have a look round and see if we were quite comfortable or needed

anything. The stewardess was a certificated nurse and cheerful under all

conditions. We were always the brighter for her visits, even whilst we

were ill. By the third morning we were quite ourselves again, and began

thoroughly to enjoy our very excellent meals, usually with the keenest

appetites, waiting for the gong to sound to get to our places in good

time for the first course.

It was the clear bracing air which made us so hungry, not

lack of food. Tea or coffee were brought to our cabin as early as we

cared to ring for it, an ample breakfast was served at eight o’clock,

delicious beef tea brought on deck at eleven o’clock, luncheon at

twelve-thirty, tea at four o’clock, dinner at six-thirty, supper at nine

p m., and anything within reason that one might ask tor between meals,

without extra charge. How liberally we fared may be seen from the copy

of the menu of our first lunch and dinner on board, which I give below.

LUNCH.

Lamb’s Head Broth.

Fried Haddock, Italian Sauce

Singapore Curry and Rice.

Boiled Leg of Mutton and Caper Sauce. Rice Espagnoli

Mashed and Plain Potatoes,

COLD.

Soused Salmon.

Roast Ribs of Beef

Canadian Ham.

Galantine of Veal

Corned Brisket of Beef.

Forequarter of Lamb and Mint Sauce. Salad.

Stewed Peaches and Custard

Eccles Cakes.

Cheese

Fruit

Tea—Coffee.

DINNER.

Consommd Julienne.

Halibut. Syrienne Sauce.

Epigrammes of Mutton, Jardiniere

Compote of Pigeons

Roast Chicken, Bread Sauce.

Roast Ribs of Beef and Yorkshire Pudding.

Turnips—Broad Beans—Roast and Plain Potatoes. Salad.

Turkish Pudding. Swiss Roll. French Ice Cream and Wafers

Desert—Cheese-—Coffee.

All this served beautifully and delicately, quickly and

hot. A bugle is sounded for first class saloon meals, a gong for second

class, and a bell for third class. The meals are informal, and you need

not sit through a long wearisome meal; everything is ready, and you may

order what you please from the menu, instead of waiting its service in

rum, as at a table d’hote meal. |