|

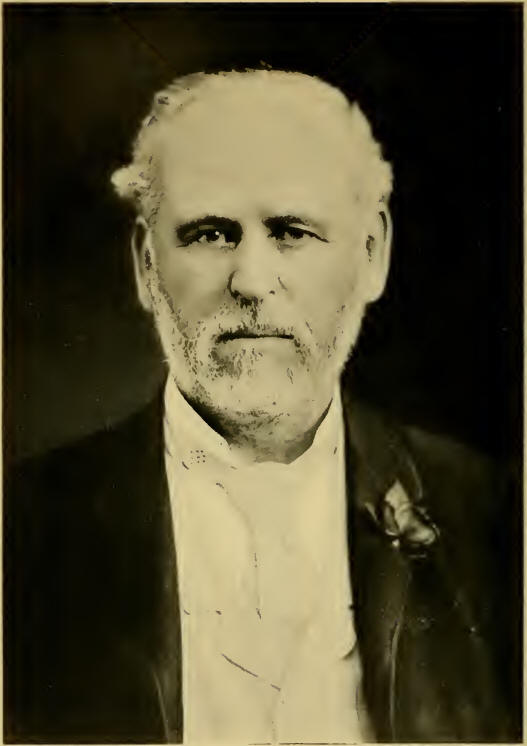

(1824-1899)

PETER MITCHELL divides

with Tilley the honor of luring timid New Brunswick into the path of

Confederation. Later he assisted in breaking the leading strings with

which the mother country sought to guide the young Dominion, and to

exercise too great control over her natural resources. For these duties

he possessed qualities of stubbornness and dash which differed from the

character of Tilley. Mitchell was a strong, dominating character, rough

and ready, and not moderated by deference. Tilley was of a finer mould,

gentlemanly and courteous. Mitchell was a shipbuilder and contractor, a

man of the world; Tilley was a druggist, a temperance advocate, and a

devoted churchman. Mitchell’s seventy-five years of life were crowded

with business, politics and the enjoyment of life. His resolute

character made him a force in any environment, but he did not accomplish

the work nor reap the honors that his abilities warranted. Though

counted by contemporaries an abler man than Tilley, he had less

stability, and therefore less usefulness in an era of great issues and

great men. Tilley was a gentle and loyal colleague of Sir John A.

Macdonald; Mitchell was headstrong, quarrelled with Sir John, and

naturally fell by the wayside.

Peter Mitchell was a characteristic product of his environment and his

time. He was born at Newcastle, N.B., on January 4, 1824. His parents,

natives of Scotland, had settled on the Miramichi six years previously.

He was educated at the local grammar school, studied law, and was called

to the Bar in 1848. The east coast of New Brunswick, then raw and new,

was embarking in the lumber business, which has persisted to this day,

and young Mitchell, with an energetic disposition, was soon immersed in

lumbering, shipbuilding and other industrial vocations. As he had a

ready tongue and was popular, he had made his first political speech at

seventeen, and was soon in politics. He was elected to the Legislative

Assembly in 1856, where he remained four years. From 1860 until

Confederation he sat in the Legislative Council, where he became a

leader. In 1867, on joining the federal Cabinet, he was appointed to the

Senate. He left that silent chamber in 1874 for the House of Commons,

but was defeated in 1878. He sat again in the House from 1882 to 1891

and met his final defeat in 1896.

Such a catalogue of dates gives a poor idea of the stormy career of this

restless, often bitter, fighting Father of Confederation. Mitchell was

not a party man. His leanings were Liberal, but he joined the Macdonald

Cabinet, and he often referred to himself as “the third party.” He was

intractable and impatient of discipline. He was often irritating in

manner, even causing annoyance to Sir John Macdonald, that master of men

in their varied moods. On one occasion Mitchell threatened to hold up

the Intercolonial Railway estimates until the Government paid for a cow,

owned by a widow in New Brunswick, which had been killed by a train. The

cow was paid for.

Mitchell had a firm and resolute manner which impressed people. He spoke

well, without notes, stood with his hands in his pockets, and came down

hard on his heels by way of emphasis. He gave the impression of mental

as well as physical power, and, though likeable, was as bold as a lion.

Early in his public career Mitchell was an advocate of the union of the

Provinces. He spoke with Howe, McGee and others at Port Robinson, Upper

Canada, in September, 1862, and presented arguments for union when as

yet such concrete suggestions were rare. Speaking of the people of New

Brunswick, Mitchell then said: “They were prepared to go into anything

and support anything which would advance the character of the colonial

possessions of Great Britain by bringing them into closer union.

Disunited, these colonies were weak. United, acting together, governed

by one public sentiment, they would be powerful and strong, and so far

from their attachment to Great Britain being weakened, would add lustre

to her throne.”

By 1864 Mitchell was a considerable figure in New Brunswick, and

attended the Charlottetown and Quebec Conferences to arrange the union

scheme, and afterwards went to the London Conference, where he supported

Cartier against Macdonald in securing the adoption of a federal rather

than a legislative union.

Before the London Conference could be called, Mitchell and Tilley passed

through the first life-and-death struggle of the union scheme. It had

been agreed to test public sentiment first in New Brunswick, but the

Province was uninformed and unsympathetic; Tilley, then Premier,

Mitchell and the other Ministers were defeated by three to one in March,

1865.

“I thought at the time, and think still, that with proper management we

ought not to have failed,” Mitchell wrote years afterwards, “and believe

the one chief cause of our failure was an injunction placed upon us of

New Brunswick at the Quebec Conference that we were not to make public

the conclusions of the conference until all the delegates had arrived at

their several Provinces and had reported at headquarters, and in

consequence of that silence the suspicions of the members and the people

of our Province were excited and set the tide against us, and we were

beaten.”

Mitchell records that on the day the Cabinet resigned he prophesied in a

conversation with Lieutenant-Governor Gordon, that a change of opinion

would take place within twelve months. Subsequent communications between

Mitchell and Governor Gordon had a most disturbing effect on New

Brunswick politics. Gordon was recalled to England for a visit, and on

his return he was seen to be a convert to the union cause, under

pressure from the Home Government. The Government of Albert J. Smith was

in power, and Tilley and Mitchell were spreading the doctrines of

Confederation among the people.

Mitchell, in his reminiscences, sets forth that Gordon called him to

Fredericton and asked him if he would support Smith, who, Gordon

believed, “could be persuaded to agree to certain terms of union,” and

wished Mitchell to take a seat in Smith’s Government, the Premier being

anxious for it. Mitchell replied that he could not do that, as Smith had

been elected by an overwhelming majority against union only six or seven

months before. “I said,” Mitchell writes, “that, while I would not go

into his Government, I would undertake, on behalf of the party I

represented—as I was more of a patriot than a politician or partisan—to

induce our party to support Mr. Smith in that measure if he was

sincere—which I told the Governor I doubted— although by so doing he

would forego all the immense patronage which the first Government of

Confederation would have at the disposal of New Brunswick.”

Negotiations proceeded, and when Mitchell insisted on a paragraph

approving Confederation being inserted in the Speech from the Throne

when the Legislature met, the members on the Government side balked—as

Mitchell expected—and the Cabinet resigned. Mitchell states that his

steps were taken after consultation with Tilley and Charles Fisher, but

when the crisis came Tilley would not take the Premiership and risk

another defeat at the polls.

“So there was nothing left for it,” Mitchell writes, with no evidence of

self-effacement, “but to accept it myself. And I did, and Mr. Tilley

seconded me ably and well. I believed we would succeed, and after going

to the country on the very same issue on which our Government was

defeated nine months before, I came back with a majority behind me of

nearly four to one, and thus was the most active and principal means of

carrying Confederation.”

Passage of the Confederation resolutions was then but a formality, and

Mitchell went with Tilley into the first Federal Cabinet.

One of the earliest and greatest struggles for Maritime Province men at

Ottawa concerned the route of the Intercolonial Railway. Its

construction was a part of the Confederation agreement, for the shreds

and patches of the new union could not subsist on summer communication

only. Mitchell favored the route along Bay de Chaleur and the east

coast, while Tilley wanted the railway to follow the St. John River, or

central, route, which was the more fertile and populous. The question

became an acute one, and seriously threatened the Government’s

stability, owing to the strength at Tilley’s disposal from the

Opposition ranks.

In the end, the argument in favor of the east coast route, supported by

a recommendation from Mr. (afterwards Sir) Sandford Fleming, the

engineer in charge, prevailed for military reasons. Mitchell’s force of

character no doubt had much to do with the decision, as he himself

freely admits.

“Mr. Tilley knew the difficulty,” he writes, “but being pledged to the

southern route, and I to the northern, he would have much preferred a

River St. John man to myself (for the Cabinet), and I believe intended

to take him. We had some very angry words over it, but my force of

character settled the matter.”

Though Mitchell was Premier of New Brunswick during the last, and

successful, stage of the Confederation battle, John A. Macdonald looked

upon Tilley as the real leader, and in 1867 asked him to join the first

Dominion Cabinet and to choose his own colleague from his own Province,

and this slight in favor of one whom Mitchell tersely terms as “my

subordinate” forms one of several indictments which he makes against

Macdonald in his reminiscences. He wrote the Dominion Premier in

protest, and says he received an apologetic reply. At least it is

unthinkable that Macdonald could not rise to such a situation, for

political jealousies were one of his most frequent subjects of

trouble—and adjustment. When Mitchell arrived to claim his portfolio

there were only two left, Secretary of State for the Provinces and

Marine and Fisheries, in neither of which posts was there anything to

do, Macdonald told him. But Mitchell took the latter, and to his

everlasting credit he found much to do. It was a new department, and he

laid it out along bold and energetic lines. He established lighthouses

and other aids to navigation on lake and sea coast, and organized the

first fleet of cruisers for the protection of Canadian fisheries.

It was as the advocate of Canadian rights in regard to fisheries that

Mitchell advanced self-government another important stage. In his

despatches in this connection he gave the keynote for subsequent

negotiations which put a curb on the encroachments of the United States

in her dealings with Canada. He was a thorough enthusiast in his

attitude towards Canadian fisheries. “As a national possession they are

inestimable,” he wrote in 1870, “and as a field for industry and

enterprise they are inexhaustible.”

Mitchell’s despatch to the Imperial Government in the same year firmly

set forth Canada’s position regarding the ownership of her fisheries. He

pointed out that in the previous December the Canadian Cabinet had

approved a report by him, in which he declined to act on the suggestion

of Her Majesty’s Government that Canada should open her coasting trade

to the United States, as Great Britain had done, while the United States

continued to close theirs against Canada. The true policy of Canada, he

insisted, was to retain all the privileges it then possessed until fresh

negotiations in regard to trade relations might reopen the whole

question.

Mitchell’s concluding words in his report to Council sound like a Bill

of Rights declared against the mother country. He said:

“The active protection of our fisheries was the first step in our

national policy, as viewed from the colonial standpoint, and has since

been followed up by legislation which has imposed certain charges upon

shipping and imposts upon articles of trade. It should, however, be

clearly understood that these restrictions and charges we are prepared

to remove whenever the United States are prepared to give us reciprocal

treatment. Till then, the public sentiment of this country calls for

vigorous action at the hands of the Canadian Government, and demands

that this, the greatest and largest question of them all, and one which

our neighbors most appreciate, shall be dealt with with spirit and vigor

and form part of an important national policy. . . .

“As part of the Empire, Canada is entitled to demand that her rights

should be preserved intact, and at least it cannot be said that Council

will have performed its duties if we silently permit ourselves to be

divested of them piecemeal, as is the case with our fishery interests,

and the people consider that their valuable fisheries are a trust

incident to Canada, and involve interests which Her Majesty holds for

the benefit of her loyal subjects, and which should not be abandoned nor

their protection neglected.”

In 1870 Mitchell engaged in a controversy with President Grant over

Canada’s fishing rights, and published a reply to Grant’s message to

Congress on the subject. He also rendered lasting service by arranging

for the fisheries arbitration at Halifax, which resulted in an award of

$4,500,000 to Canada for the use of Canadian fisheries by United States

fishermen.

Though Mitchell as a Liberal had joined the Macdonald Cabinet, he was

not within its inner councils. At the end of the session of 1873, he

says, he asked Sir John to allow him to resign, as he felt he had been

slighted, but was persuaded to remain until after the recess. Meantime

the Pacific Scandal storm broke in all its intensity. Mitchell hastened

to Ottawa, but declares he was given no explanation, and had no

information except what all could read in the newspapers. In the House,

after it was called, the charges and replies dragged on for days, but

Mitchell declined to speak in defence. One dramatic incident, however,

he witnessed and describes. There was much concern over the expected

speech and attitude of Donald A. Smith (afterwards Lord Strathcona), and

Mitchell, at Tup-per’s request, arranged an interview between Macdonald

and Smith with a view to a reconciliation. When Smith came from

Macdonald’s room the failure of the purpose was evident. Mitchell says:

“I saw by the expression and color of his face that he was very much

excited, and I feared it was all up with us. Mr. Smith came along to

where I sat and said to me:

“‘Oh! Mitchell, he’s an awful man, that. He has done nothing but swear

at me since I went into the room.’

“Mr. Smith said: ‘I don’t want to vote against your Government, and

particularly on your account, Mr. Mitchell, because you have always

treated me very fairly, but there is nothing else for me to do, and I

will have to do it.’"

Smith’s arraignment of the Government that night marked the turning

point, and the Government resigned next day.

Mitchell’s later years were somewhat embittered and uneventful. He used

to say that, after all, there was small satisfaction in serving one’s

country, for no matter what one did it soon forgot one. He became

proprietor of the Montreal Herald in 1885, but took little part in its

editorial management. He was not in Parliament after 1891, and after

unsuccessfully seeking an appointment from the Conservative Government,

was made Inspector of Fisheries for Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova

Scotia by the Laurier Government in March, 1897. He was then an old man,

and lived by himself at the Windsor Hotel in Montreal. In the summer of

1899 he had a partial stroke of paralysis while in Ottawa, but

afterwards went about apparently in good health. On October 25 the

second attack came, and the next morning he was found dead in his room

at the hotel.

Peter Mitchell was buried in his native town of Newcastle, N.B., and

though he had outlived nearly all of his political contemporaries, his

death removed a valiant, if stormy statesman, whose services become more

significant as the years pass. |