|

So far as events of

historical importance or of public interest are concerned, I have done

what remains to be recorded relates only to Murray's private life, when,

after the episode related in the last chapter, he retired to his Sussex

estate, there to reflect on the inconstancy of princes and the unwisdom

of those that put trust in them. The King did not easily forgive what he

deemed obstinacy on the part of a subject, who had refused to accept the

royal advice in a matter which concerned his honour, and, without

friends at Court to support his cause, and no inclination to push it

himself, the gallant defence of Minorca and the insult that followed by

way of reward were soon forgotten. On February 19, 1783, Murray was

promoted to the rank of full General. This could scarcely be called a

recognition of his services, for it was merely a promotion, following

the custom of the time, of a batch of lieut.-generals of the same date

of rank, of whom he was one, but at least it served as an indication

that the court martial had not found him wanting. His ambition to

command the Scots Greys was never fulfilled. The King had promised it,

but when two years later the regiment became vacant it was given to

Lieut.-General James Johnston. At the same time Murray was appointed

Governor of Hull—one of those military governorships which at the time

were numerous, and served as rewards for officers of meritorious

service, without necessitating residence. Possibly this

appointment instead of the Greys was made with his concurrence; there is

nothing to show, but in 1789 he obtained his desire to command a Scots

regiment by being transferred to the 21st, then known as the Royal North

British Fuzileers, now the Royal Scots Fusiliers, a famous regiment

which had borne an honourable share in all the battles of Marlborough's

campaigns and many that followed.

It is recorded of Lord

Shelburne, when at about this period he was forced from office, that he

found himself "immersed in idle business, intoxicated with liberty and

happy in his family." In very similar mood Murray wrote to his friend

Dr. Mabane in Quebec:

"I, at the age of

sixty-six, enjoy perfect health and happiness, truly contented with my

lot of independent mutton. I enjoy the comfortable reflection that I

have ever zealously acquitted myself a faithful friend to my country and

its Sovereign. Having laid aside every ambitious view, and as great a

farmer as ever, I never think of St. James', and am only anxious for the

prosperity of my two delightful children and the cultivation and

increase of my fields and garden, all which objects are due to my

heart's content."

Truly, I think, this

unconscious picture of a mind undisturbed by a life, which had had a big

share of stirring events, is a tribute to a loftiness of character which

requires no better illustration.

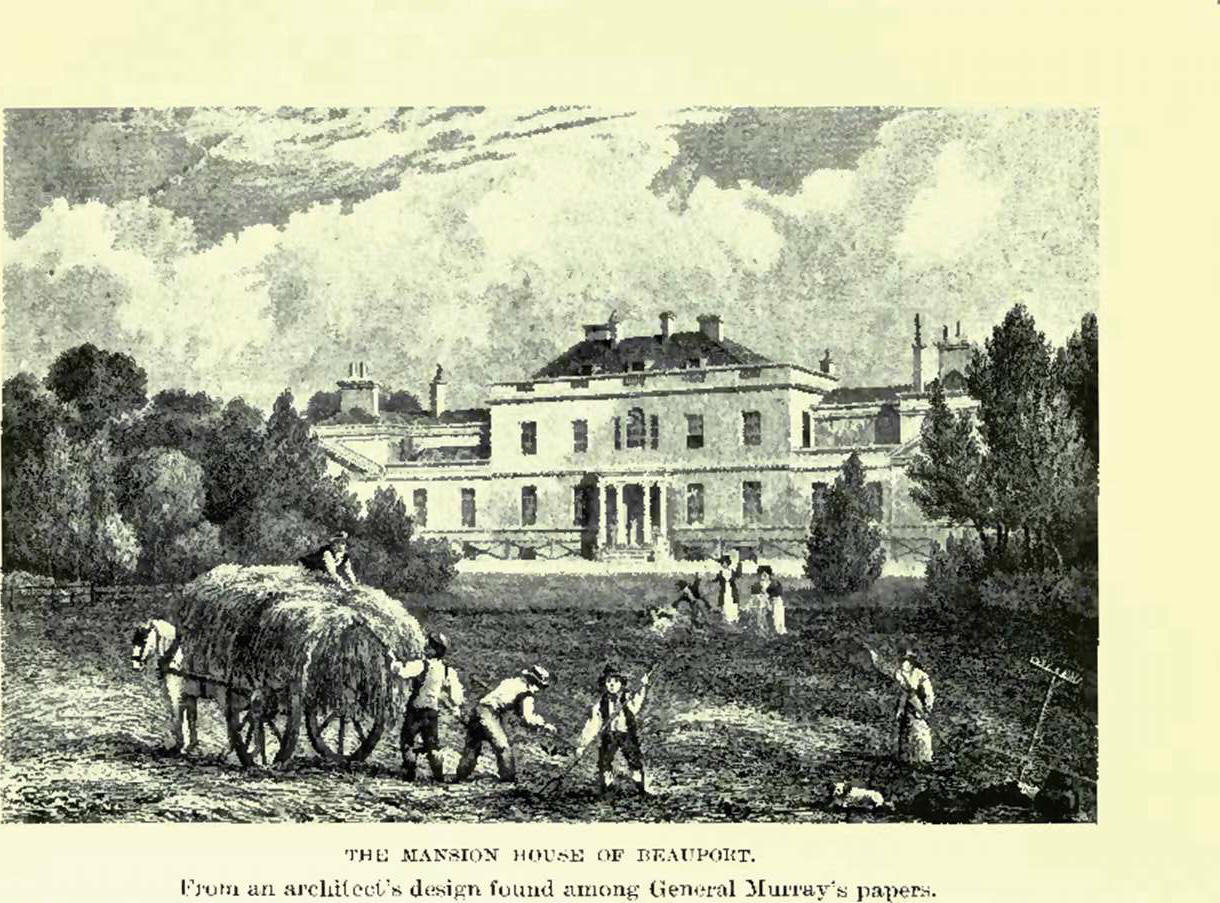

On Beauport he expanded

all his care and energy. To increase the beauty of that already

beautiful home became to him a sufficient aim, which served to

obliterate the disappointments of the past. From here he could revel in

vistas of wide land and sea-scapes—the Bay of Rye, the Romney Marshes,

Dungeness Point; on a fine clear day Cape Grisnez and the high ground

surrounding Boulogne;

westwards the coastline

as far as Beachy Head could be traced, with the long ridges of the South

Downs; northward the horizon is bounded by that high upland known as the

backbone of Kent, and, traditionally, occasional views as far off as

Sevenoaks—a place for an artist to rejoice in, and, in fact, J. W. M.

Turner in later years spent much time in the neighbourhood, and has left

sketches of Battle Abbey, Asliburnham Place, Crowhtirst Place, and also

one called "Beauport, near Bexhill," though certainly Turner's

"Beauport" is not the Beauport of reality. The house itself he greatly

enlarged. In this pleasant home Murray spent the remaining twelve years

of his life, and here his many friends enjoyed his hospitality and

talked over stirring times or discussed the prospect of the farms, for

the owner of Beauport was always a keen farmer. Here several children

were born to him, and altogether there were six children of the second

marriage, of whom four survived him, the last having been born in 1793,

when Murray was nearly seventy-four years old. It is interesting to note

that among the visitors to Beauport, but after James Murray's time, was

Isaac Disraeli, accompanied by his famous son Benjamin, Lord

Beaconsfield. Sixty years later, meeting the present owner of Beauport,

he remembered these visits at once, saying, " I used to visit the house

with my father. It had a very pretty garden and a splendid view of the

channel towards Dover."

Besides Beauport, he

was Lord of the Manor of Ore, and the property of Ore Place was in his

possession; but I believe he had only a life interest in it, through the

first Mrs. Murray. In this old house he had resided in former years

while Beauport was being rebuilt, and he retained a lasting affection

for it. Tradition has it that the Manor House was built by John of

Gaunt, and it may be that Murray's feelings towards it were prompted by

his own descent from that old-time hero, whose record of battles and

sieges would be sure to inspire his admiration. It was in the old church

of Ore that he erected the family vault, and here he himself was buried.

In the New World, too,

Murray had considerable possessions. The record is not very clear, but

he certainly possessed a large estate situated on the shores of Lake

Champlain, which he purchased in 1764 from M. Francois Foucault.

The other principal

property was the estate of Lauzon or Point Levis, purchased from a M.

Cherast in 1765. This would be a valuable property to-day, extending for

six leagues along the St. Lawrence, and including the parishes of St.

Joseph, St. Henry, St. Nicholas, and part of St. Charles, that is to

say, the area from the old landing place at Point Levis up to and

including the parish of St. Nicholas, which lies opposite St. Augustin

beyond Cap Rouge. This is now a well-populated area, with many important

mills, dockyards, and factories, and would be a princely possession; but

in Murray's time the annual value of the property amounted to no more

than £358 13s., and out of this had to be deducted all expenses

attending collection of rents and the wear and tear of the mills.

There appear to have

been other properties in Canada, but the record on this head is very

obscure. By his will, dated September 6, 1793, he left these properties

to his son James Patrick Murray, who was born at Leghorn on January '25,

1782, subject to a life interest in Beauport to his wife, and a charge

of £5000 each to his three surviving daughters, the executors having

power to raise any defect of these sums by mortgage on the American

estates, the widow to receive an allowance of £400 a year besides an

allowance for each child. There are, unfortunately, no details available

in the will or elsewhere as to the property, and practically no

information as to why or when it was sold; but the probability is that

the executors, of whom there were three—his two nephews, Sir James

Murray and William Young, being two of them—were obliged to sell the

lands in order to provide the daughters' portions.

James Murray died at

Beauport on June 18, 1794, in his seventy-fifth year, and was buried, in

accordance with his desire, in the old church at Cre. In the foregoing

chapters I have endeavoured faithfully to portray the achievements and

character of one who was a maker of history at a time when the

foundations of the British empire were being laid. If I have been

successful I have given the impression of a man who was generous to an

extraordinary degree, even perhaps to an extent which savoured a little

of ostentation. He undertook, with a readiness which rather outran his

means, the education of his nephews and provision for relatives not well

endowed. It was customary for men of his position to affect a

magnificence which many could not afford, and he was certainly no whit

behind them. It cannot be denied that he was autocratic and

hot-tempered—he quarrelled with many; but if he found himself in the

wrong he made the best amends he could think of, and it must be admitted

that in the majority of cases the enemies he made were of persons of

little worth, with whom his ultra strict notions of honour permitted no

friendship. With those of his opponents in war, who proved themselves

worthy, he was on terms of friendship when circumstances permitted. For

De Levis, for instance, whom he regarded as preux chevalier, he had the

greatest regard and frequently corresponded with him. For Vaudreuil, on

the other hand, he expressed the bitterest contempt as of a man who had

betrayed his trust. Of political acumen I have given proof that he

possessed a singular gift; but as a politician, that is, one capable of

securing his desires by opportunism, he was defective—he was too blunt

and downright, too honest, in fact, to please minds accustomed to reach

their goal by roundabout methods. Thus he often failed to secure a

successful issue where he had pointed the way, and others of less merit

secured the applause and the honours which were his due. He lived in a

corrupt age, and one which, according to our standard, was immoral. When

he sent his brother George's natural son to Amherst, the latter had

replied: "I shall be very glad to see Mr. Patrick Murray, and do

anything for him that you desire, and if you will send me one or two of

your own I will convince you what a regard I have to Marshal Saxe's

scheme!" Yet in all the papers 1 have been through there is nothing to

show that he had occasion to take advantage of Amherst's offer. He had,

however, been elected a Knight of the Ancient Order of the Beggar's

Benison,* a society of wits whose foundation was on much the same lines

as the famous club at Medmenham Abbey, and whose morals were on about

that level. He lived long enough to see an immense improvement in public

life, the reform of parliamentary representation, and the abolition of

that worst form of mis-government, the sale of offices to the highest

bidder. In this great reform, Lord Shelburne, to his honour, led the

way, but before he had enunciated his principles Murray had, so far as

his opportunities admitted, taken action in the practical application of

them.

There was a certain

genius, almost of eccentricity, in all the children of Alexander Lord

Elibank and his wife, Elizabeth Stirling, and none showed it more than

the eldest, Patrick, Lord Elibank, of whom even Dr. Johnson could speak

with admiration, and James, the youngest, who should be better known as

one of the makers of the Dominion of Canada, if not as the chief

builder. His greatest glory was that he sacrificed himself to befriend

the Canadians, oppressed by a Government too short-sighted to see the

immense part which Canada could play as an integral part of the empire—a

part, which the event of 1914 to 1918 has demonstrated to the full. If

James Murray lived his life as an aristocrat, he was ever the friend of

the people, without indulging in that excess of championship which,

*The Order of the

Beggar's Benison was established at Anstruther in Scotland about the

year 1739, and included in its membership eminent men of all classes,

even some members of the royal family. Its motto—"Be fruitful and

multiply"—serves to indicate the hedonic nature of its orgies.

Apparently the "Hell-Fire Club," installed at Medmenham Abbey in 1742,

with the motto, "Fay cc que voudras," was a foundation following the

same lines, where a group of brilliant wits, among whom, by the way, was

John Wilkes— Murray's bitter detractor—carried on a secret ritual of

blasphemous revelry. Both orders were, no doubt, an attempt to put In

practice the Rabelaisian conceptions of the Abbey of Theldme. As

Murray's biographer, I must add that I do not think he ever had

opportunity of taking up his membership.

in many cases at this

period, was not without a suspicion of selfish motives. It was never his

method to belittle others, or to harass the men in power that he might

gain credit for himself. He lived as a gentleman should, and acted up to

the motto of his family, "Virtute Fideque." |