|

THURSDAY evening found us

striking southward, Mr. Woolsey and his interpreter, William Monckman,

making our party up to five. Peter was guide and father's interpreter. Both

positions he was well able to fill.

Because of Mr. Woolsey's

physical infirmity, we were obliged to travel more slowly than we had thus

far.

Our road ran along the east

side of Smoking Lake, and down the creek which runs from the lake to the

Saskatchewan. We had left most of the ox for the men at the Mission, and

were to depend upon our guns for food until we should reach the Indian camp

on the plains. We shot some ducks for supper and breakfast the first night

out, and reached the north bank of the river Friday afternoon. The

appearance of the country at this point and in its vicinity pleased father

so much that he suggested to Mr. Woolsey the desirability of moving to this

place and founding a mission and settlement right here on the banks of the

river, all of which Mr. Woolsey readily acquiesced in.

The two missionaries,

moreover, decided that the name of the new mission should be Victoria.

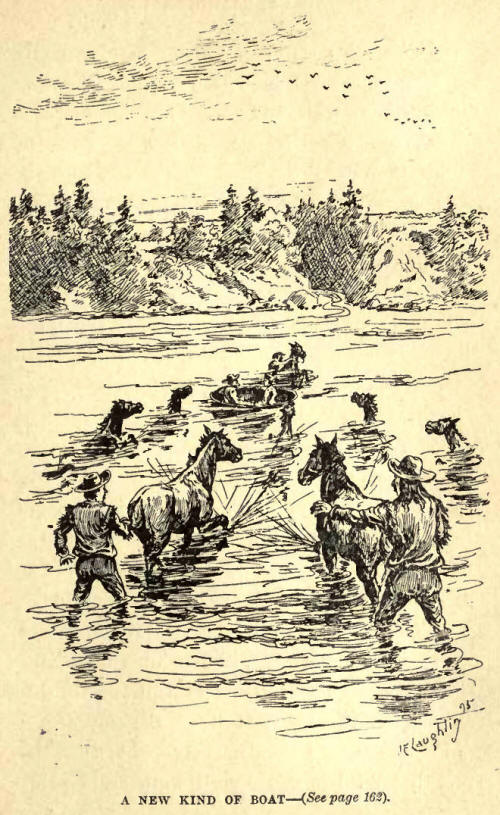

The next move was to cross

this wide and swiftly flowing river. No ferryman appeared to answer our

hail. No raft or canoe or boat was to be seen, no matter where you might

look. Evidently something must be improvised, and, as it turned out, Peter

was equal to the occasion.

Father and Mr. Woolsey had

gone to further explore the site of the new mission, William was guarding

the horses, and Peter was left with myself to bridge the difficulty, which,

to me, seemed a great one. If we had even a small dugout or log canoe, I

would have been at home.

But what is Peter going to do

?" was the question I kept asking myself. Presently I said, "How are we

going to cross?" "Never you mind," said he; "do as I tell you." "All right,"

said I; and soon I received my instructions, which were to go and cut two

straight, long green willows about one and a half inches in diameter. I did

so, and Peter took these and with them made a hoop. While he was making this

he told me to bring the oilcloth we were carrying with us and to spread it

on the beach. Then he placed the hoop in the centre of the oilcloth, and we

folded it in on to the hoop from every side. Then we carried our saddles,

and blankets, and tent, and kettle, and axe—in short, everything we had, and

put them in this hoop. Then William came and helped us carry this strange

thing into the water. When we lifted by the hoop or rim our stuff sagged

down in the centre, and when we placed the affair in the water, to my great

astonishment it floated nicely, and I was told to hold it in the current;

and Peter, calling to the missionaries, said, "Take off your shoes,

gentlemen, and wade out and step into the boat." I could hardly credit this;

but the gentlemen did as bidden, and very soon were sitting in the hoop, and

still, to my great wonder, it floated.

Peter, in the meantime, took

a "chawed line."

This is made of buffalo hide,

and is literally what its name signifies, having been made by cutting some

green hide into a strand, about an inch or more wide, and stretching this,

and as it dried, scraping the hair and flesh from it. When thoroughly dry

the manufacturer began at one end and chewed it through to the other end,

and then back again, and continued this until the line was soft and pliable

and thoroughly tanned for the purpose. Great care was taken while chewing

not to let the saliva touch the line. These lines were in great demand for

lassos, and packing horses, and lashing dog sleighs and as bridles.

Peter tied one end of this

securely to the rim of the hoop, and then brought a horse close and tied the

other end of the line to the horse's tail; then fastening a leather hobble

to the under jaw of the horse, he vaulted on to its back and rode out into

the stream, saying to me, "Let go, John, when the line comes tight;" and

gently and majestically, like a huge nest, with the two missionaries sitting

as eaglets in it, this strange craft floated restfully on the current.

For a moment I stood in

amazement; then the fact that William and myself were still on this side

made me shout to Peter, "How are we to cross?" By this time he was swimming

beside his horse, and back over the water came the one word, cc Swim !" then

later, "Drive in the horses and take hold of the tail of one and he will

bring you across." I could swim, but when it came to stemming the current of

the Saskatchewan, that was another matter.

However, William and I did as

our guide ordered, and soon we were drying ourselves on the south bank,

horses and men and kit safely landed. The willow pole and our oilcloth had

borne our missionaries and guns and ammunition, and the whole of our

travelling paraphernalia, without wet or loss in any way.

As soon as the backs of our

horses were dry, we saddled and packed, and climbing the high bank of the

river, proceeded on our journey.

Peter cautioned us by saying,

"We must keep together as much as possible; there must be no shooting or

shouting towards evening; we are now where we may strike a war party at any

time."

All this made the whole

situation very interesting to me. I had read of these things; now I was

among them.

We stopped early for supper,

and then went on late, and camped without fire, another precaution against

being discovered by the enemy.

Next morning we were away

early, and were now reaching open country. Farms and homesteads ready made

were by the hundred on every hand of us.

Our step was the "all-day

jog-trot."

Presently father, looking

around, missed Mr. Woolsey, and sent me back to look for him and bring him

up. I went on the jump, thankful for the change, and finding Mr. Woolsey, I

said, "What is the matter? They are anxious about you at the front." He

replied by saying, "My horse is lazy." "Old Besho is terribly slow. Let me

drive him for you," said I; and suiting the action to the word, I rode

alongside and gave "Mr. Besho" a sharp cut with my "quirt." This Besho

resented by kicking with both legs. The first kick came close to my leg, the

second to my shoulder, the third to my head. This was a revelation to me of

high- kicking power. Thinks I, Besho would shine on the stage; but in the

meantime Mr. Woolsey was thrown forward, for the higher Besho's

hind-quarters came, the lower went his front, and Mr. Woolsey was soon on

his neck, and I saw I must change tactics. So I rode to a clump of trees,

and securing a long, dry poplar, I came at Besho lance-like ; but the

cunning old fellow did not wait for me, but set off at a gallop on the trail

of our party. Ah! thought I, we will soon come up, and I waved my poplar

lance, and on we speeded; but soon Mr. Woolsey lost his stirrups and

well-nigh his balance, and begged me to stop, and I saw the trouble was with

my friend rather than his steed.

However, we came up at last,

and were careful after that to keep Mr. Woolsey in the party.

This was Saturday, and we

stopped for noon on the south side of Vermilion Creek, our whole larder

consisting of two small ducks. These were soon cleaned and in the kettle and

served, and five hearty men sat around them, and father asked Mr. Woolsey

what part of the duck he should help him to. Mr. Woolsey answered, "Oh, give

me a leg, and a wing, and piece of the breast," and I quietly suggested to

father to pass him a whole one.

As we: picked the duck bones,

and I drank the broth, for I never cared for tea, we held a council, and

finally, at father's suggestion, it was decided that Peter and John (that

is, myself) should ride on ahead of the party and hunt, and if successful,

we would stay over Sunday in camp; if not, we would travel.

|