|

FATHER had suggested two

plans for immediate action : One was to send William out to the plains to

trade some provisions; the other was to send me to the site of the new

mission, and have me make some hay and plough some land ready for next

spring, and thus take up the ground.

Mr. Woolsey decided to act on

both. The former was very necessary, for we were living on duck, rabbits,

etc., and the supply was precarious.

William took an Indian as his

companion, and I a white man, by the name of Gladstone, as mine.

We travelled together as far

as the river. This time we took a skiff Mr. Woolsey had on Smoking Lake.

We took this as far as we

could by water and then loaded it on to a cart, and when we reached the

river we took William's carts apart and crossed them over, and he and his

companion started out to look for provisions, while Gladstone and myself to

put up hay and plough land.

For the former we had two

scythes, and for the latter a coulterless plough; but we had a tremendously

big yoke of oxen.

We pitched our lodge down on

the bank of the river and went to work; but as we had to hunt our food as

well as work, we did not rush things as I wanted to.

My companion had been a long

time in the Hudson's Bay Company's service, but was a boat-builder by trade,

and knew little about either haymaking or ploughing or hunting; but he was a

first-rate fellow, willing always to do his best. He told me that though he

had been in the country for a long time, he had seldom fired a gun and had

never set a net.

We had between us a

single-barrelled shotgun, percussion-lock, and a double-barrelled flintlock.

The first thing we did was to

make some floats, and put strings on some stones, and I tied up a net we had

and we crossed the river, and set it in an eddy; then we fixed up our

scythes and started in to cut hay on the ground where we intended to plough.

We had several horses with

us, and these and the oxen gave us a lot of trouble. Many an hour we lost in

hunting them, but we kept at it.

At first our food supply was

good. I caught several fine trout in my net, and shot some ducks and

chickens. We succeeded in making two good-sized stacks of hay.

Then we went to ploughing,

but our oxen had never pulled together before—good in the cart, but hard to

manage in double harness. It was not until the second day, after a great

deal of hard work, that we finally got them to pull together.

Then our plough, without a

coulter, bothered us tremendously; but we staked out a plot of ground, and

were determined, if possible, to tear it up.

Once our oxen got away, and

we lost them for three days. "Glad," as I called him, knew very little about

tracking, and I very little at that time, but the third day, late in the

evening, I came across the huge fellows, wallowing in pea- vine almost up to

their backs, and away they went, with their tails up, and I had to run my

horse to head them off for our tent.

One morning, very early, I

was across looking at my net, and caught a couple of fine large trout.

Happening to look down the river, I saw some men in single file coming along

our side, keeping well under the bank. My heart leaped into my mouth as I

thought of a war- party; but as I looked, presently the prow of a boat came

swinging into view around the point, and I knew these men I saw were

tracking her up.

What a relief, and how

thankful I was to think I might hear some news of home and father and the

outside world, for though it was now more than four months' since I left

home, I had not heard a word. I hurried up and fixed my net, and pulled

across and told Glad the news about the boat, and he was as excited as

myself.

Isolation is all very fine,

but most of us soon get very tired of it. I for one never could comprehend

the fellow who sighed, "Oh, for a lodge in some vast wilderness!" Very soon

the boat came to us, and we found that it contained the chief factor,

William Christie, Esq., and his family, and was on its way to Edmonton. Mr.

Christie told me about father passing Canton in good time some weeks since,

and assured me that he would now be safe at home at Norway House. He said

that there was no late packet and he had no news from the east.

He went up and looked at our

ploughing, and laughed at our lack of coulter. "Just like Mr. Woolsey, to

bring a plough without a coulter," said he; but the same gentleman bought a

lot of barley of us some three years after this.

They had hams of buffalo meat

hanging over the prow and stern of their boat. I offered them my fish,

hoping they would offer me some buffalo meat. They took my fish gladly, but

did not offer us any meat. This was undoubtedly because they did not think

of it, or they would have done so, but both Glad and I confessed to each

other afterwards our sore disappointment.

However, we ploughed on.

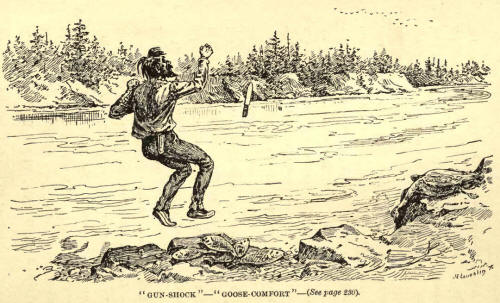

One morning I had come ashore

from the net with some fish in my boat, and, going up to the tent, Glad went

down to the river to clean them. In a little while I looked over the bank,

and, sitting within a few feet of Glad (who was engaged with the fish, just

at the edge of the water), was a grey goose, looking earnestly at this

object beside him; but as Glad made no sudden movement, the goose seemed to

wonder whether this was alive or not. I slipped back for my gun and shot the

goose, and Glad who thought somebody was shooting at him, jumped for his

life, but I pointed to the dead goose and he was comforted.

Philanthropists make a great

mistake when they begin to comfort others through their heads. Let them

begin at their stomachs, which makes straighter and quicker work.

We were still three or four

days away from our self-set task, when, as if by mutual agreement, the fish

would not be caught, the ducks and geese took flight south, and the chickens

left our vicinity. To use a western phrase, "The luck was agin' us." We had

started with two salt buffalo tongues as our outfit, when we left Mr.

Woolsey. We had still one of these left. We boiled it, and ate half the

first day of our hard luck. We worked harder and later at our ploughing the

second day. We finished the tongue and ploughed on. The third day we

finished our task about two o'clock, and then I took my gun and hunted until

dark, while Glad gathered and hobbled the horses close to camp. Not a rabbit

or duck or chicken did I see.

If ii had been a pagan

Indian, I would have said, "Mine enemy hath done this. Somebody is working

bad medicine about me." But I had long before this found out that the larder

of a hunter or fisherman is apt to be empty at times.

Glad and I sat beside our

camp-fire that night, and were solemn and quiet. There was a something

lacking in our surroundings, and we felt it keenly. For a week we had been

on very short "commons," and since yesterday had not tasted any food, and

worked hard. In the meantime, there is no denying it, we were terribly

hungry.

Early next morning we took

down our tent and packed our stuff. We had neither pack nor riding-saddles,

as we had come this far with William, and we had hoped that he would have

returned before we were through our work; but going on the plains was going

into a large country.

You might strike the camp

soon, or you might be weeks looking for them, and when you found the

Indians, they might be in a worse condition as to provisions than you were.

This all depended on the buffalo in their migrations —sometimes here, and

again hundreds of miles away. William may turn up any time, and it may be a

month or six weeks before we hear from him. As it is, Glad and I do the best

we can without saddles, and start for home.

Having the oxen, we went

slow.

After travelling about ten

miles, I saw someone coming towards us, and presently made out that it was a

white man, and I galloped on to meet him, and found that it was Neils, the

Norwegian, who was with Mr. Woolsey. He was on foot, but I saw he had a

small pack on his back, and my first question was, "Have you anything to

eat?" and he said he had a few boiled tongues on his back. Then I told him

that Glad and I were very hungry, and would very soon lighten his pack. He

told me Mr. Woolsey had become anxious about us, and at last sent him to see

if we were still alive. When Glad came up, we soon showed Neils that our

appetites were fully alive, for we each took a whole tongue and ate it; then

we split another in two and devoured that. And now, in company with Neils,

we continued our journey, reaching Mr. Woolsey's the same evening, but

making great attempts to lower the lakes and creeks by the way, for our

thirst after the salt tongues was intense.

|