|

THE next thing was to

establish a fishery.

The buffalo might fail us,

and so might the fish, but we must try both; and as I happened to be the

only one in our party who knew anything about nets and fishing, this work

came to me. So I began to overhaul what nets Mr. Woolsey had, and went to

work mending and fixing them up.

About twenty-five miles north

of us was a lake, in which a species of white-fish were said to abound, and

our plan was to make a road out to that and give it a fair trial.

In the meantime, because of

an extra soaking I got in a rain storm, I had a severe attack of

inflammation, and, to use another western phrase, had a "close call." But

Mr. Woolsey proved to be a capital nurse and doctor combined. He physicked,

and blistered, and poulticed for day and night, and I soon got better, but

was still weak and sore when we started for the lake.

I took both Glad and Neils

with me, our plan being to saw lumber and make a boat, and then send Glad

back, and Neils and I go on with the fishing.

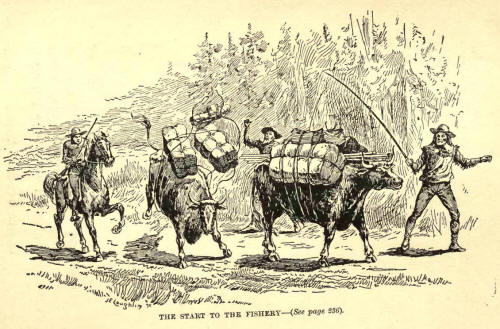

Behold us then started, the

invalid of the party on horseback, and Glad and Neils each with an axe in

hand, and leading an ox on whose back our whole outfit was packed— buffalo

lodge tents, bedding, ammunition, kettles, cups, whip-saw, nails, tools,

everything we must have for our enterprise.

These oxen had never been

packed before, and were a little frisky about it, and several times made a

scattering of things before they settled down to steady work.

We had to clear out a great

deal of the way, and to find this way without any guide or previous

knowledge of the place; but our frontier instinct did us good service, and

early the third day we came out upon the lake, a beautiful sheet of water

surrounded by high forest-clad hills.

We had with us ten large

sleigh dogs, and they were hungry, and for their sakes as well as our own,

we hardly got the packs and saddles off our animals when we set to work to

make a raft, manufacturing floats and tie-stones, and preparing all for

going into the water. Very soon we had the net set; then we put up our

lodge, and at once erected a saw-pit, and the men went to work to cut lumber

for the boat we had to build.

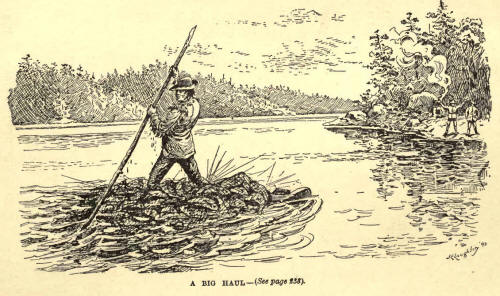

Before long, in looking out

to where we had set the net, I saw that all the floats had disappeared under

the water. This indicated that fish were caught, and I got on the raft and

poled out to the net. My purpose was to merely overhaul it, and take the

fish out, leaving the net set; but I very soon saw that this was impossible.

I must take up the net as it was, or else lose the fish, for they would flop

off my raft as fast as I took them out of the net; so I went back to the end

of the net and untied it from the stake, and took in the whole thing.

Fortunately the net was short

and the lake calm, for presently I was up to my knees in water, and fish, a

living, struggling, slimy mass, all around me, so that my raft sank below

the surface quite a bit. Fortunately, the fish were pulling in all possible

contrary directions, for if they had swam in concert, they could have swum

away with my raft and myself. As it was, I poled slowly to the shore, and

shouted to my men to come to the rescue, and we soon had landed between two

and three hundred fish —not exactly, but very nearly white-fish. As to

quality, not first-class by any means; still, they would serve as dog food,

and be a guarantee from starvation to man.

We had found the lake. We had

found the fish, and now knew them to be plentiful; so far, so good. After

the dogs were fed and the fish hung up, and the net drying, I began to think

that I was running the risk of a relapse. So I took my gun and started out

along the lake to explore, and make myself warm with quick walking. I went

to the top of a high hill, saw that the lake was several miles long, shot a

couple of fall ducks, and came back to the camp in a glow; then changed my

wet clothes, and was apparently all right.

While the men were sawing

lumber, and chopping trees, and building the boat, I was busy putting up a

stage to hang fish on, and making floats and tying stones, and getting

everything ready to go to work in earnest when the boat was finished.

This was accomplished the

fourth day after reaching the lake, and Glad took the oxen and horse and

went back to Mr. Woolsey.

Neils and I set our net and

settled down to fishing in good style.

We soon found that the lake

abounded in worms, or small insects, and these would cling to the net, and

if the net was left long in the water, would destroy it, so we had to take

it up very often; and this with the drying and mending and setting of nets,

and making of sticks and hanging of fish, kept us very busy. So far north as

we were, and down in the valley, with hills all around us, and at the

short-day season, our days were very short, and we had to work a lot by

camp-fire, which also entailed considerable wood-cutting.

Our isolation was perfect. We

were twenty- five miles from Mr. Woolsey; he and Glad were sixty from

White-fish Lake and 120 from Edmonton, and both of these places were out of

the world of mail and telegraph connection, so our isolation can be readily

imagined.

Many a time I have been away

from a mission or fort for months at a time, and as I neared one or other of

these, I felt a hungering for intelligence from the outside or civilized

world; but to my great disgust, when I did reach the place, I found the

people as much in the dark as myself.

But this isolation does not

agree with some constitutions, for my Norwegian Neils began to become morbid

and silent, and long after I rolled myself in my blanket he would sit over

the fire brooding, and I would waken up and find him still sitting as if

disconsolate. At last I asked him what was the matter, when he told me it

was not right for us to be there alone.

You take your gun and go off.

If a bear was to kill you?" (We had tracked some very big ones.) "You will

go out in the boat when the lake is rough; if you were to drown, everybody

would say, 'Neils did that—he killed him.'" On the surface I laughed at him,

but in my heart was shocked at the fellow, and said, If anything was to

happen to you, would not people think the same of me? We are in the same

boat, Neils, but we will hope for the best, and do our duty. So long as a

man is doing his duty, no matter what happens, he will be all right. You and

I have been sent here to put up fish; we are trying our best to do so; let

us not borrow trouble."

For a while Neils brightened

up, but I watched him.

|