|

The Dominion of Canada occupies the northern

portion of the continent of North America—exclusive of Alaska: all

the Arctic islands between Greenland and the 141st meridian being

included within its boundaries. Its area is about 3,729,665 square

mile-.1 The island of

Newfoundland—including some of the lesser islands on the east coast

of the continent—and a narrow strip of land along the adjacent

Labrador coast, forms a separate colony, under the British Grown.

Inclusive of Newfoundland, British North America has an area of

about 3,772,000 square miles. Canada extends from east to west about

3500 miles, and from north to south about 1400 miles. The most

southern point is in Essex countv, Province of Ontario, near

latitude 42° 16' N.

This large area necessarily presents great

diversity of topographic features, and strata of nearly all

geological horizons are represented. On the basis of certain

structural features, it is possible to recognize six great

physiographic units. The greatest single structural unit covers an

area of over 2,000.000 square miles. This unit extends, in a more or

less U shape, from Labrador on the east to Coronation gulf on the

west, bordering the great Hudson Bay depression. It is underlain by

a mass of ancient crystalline rocks, very diverse, and highly

metamorphosed—the roots of the most ancient mountain range on the

continent. These mountains were probably the first land areas of the

North American continent. The originally overlying portions were

gradually removed by various erosive processes, until now,

throughout this vast area, mountain forms are no longer seen; but

their basal structures still remain. So great has been erosion, that

the region is now characterized almost everywhere by the existence

of remarkably even skylines. Here and there, low domed residuals

rise a few feet above the general level, making notable breaks in

the otherwise nearly even surface.

•In detail the topography of this area is

characterized by innumerably small domes and basins, with a relief

of only a few hundred feet or less. Scattered over its surface are

numberless small and large lakes, with numerous streams, which

exhibit many rapids and falls. Nowhere else in the world are small

lakes and connecting streams so plentiful and so widely distributed.

The greater portion of the southern part of the region is covered

with dense forests of spruce. The higher portions of the area in

Labrador, and the extreme northern portions of both the eastern and

western limbs, are nearly destitute of trees; although some few

occur in protected basins. The remarkably even skyline, and certain

other features which characterize the region as a whole, have caused

it to be designated the

Laurentian Peneplain. It is, however, a

very ancient peneplain, which has been elevated and partially

dissected and denuded, producing the present hummocky topography.

The elevation of the plane, as shown by the skylines, varies from

about 500 feet above the sea-level to about 1.100 feet, a very

considerable portion lying below the 1000 ft. contour. The area is

sometimes known as the

Laurentian Plateau.

This area is underlain by ancient crystalline

rocks, ranging from the Laurentian to the Kewecnawan formations. It

is a region of great potential importance as a producer of minerals

of economic value. The mica and phosphate deposits of the Ottawa

valley; the silver mines of Cobalt; the gold deposits of Porcupine;

the nickel-copper deposits of Sudbury; and the iron mines of the

Michipicoten district, all occur within this region. Its

importance—already demonstrated as a source of such minerals as

graphite, feldspar, mica, corundum, iron ores, both magnetites and

hematites, silver, cobalt, copper, nickel, and gold—will,

undoubtedly, be greatly extended in the future.

The

Hudson Bay basin occupies a central

depression in the Laurentian peneplain. The bay itself is a great

inland sea, some 000 miles from east to west, and nearly 1000 miles

from north to south. Bordering the southern and southwestern portion

of this basin, is an area underlain by Palaeozoic rocks, sloping

gently bayward, which may be designated the

Hudson Bay Coastal Plain. At present this

region is largely unexplored, but is known to contain deposits of

rock salt and gypsum.

Southeast of the Laurentian plateau, including a

portion of the province of Quebec (south of the St. Lawrence river

and east of Sherbrooke) and the whole of the Maritime Provinces, we

find the northern extremity of the belt of Appalachian mountain

folds, which extends along the Atlantic coast of the continent. This

area was termed the

Acadian region by Dawson. It is underlain

chiefly by Palaeozoic rocks, which have been subjected to

considerable folding, and, afterwards, were degraded. On the extreme

east, on the Xova Scotia coast, a number of basins contain residuals

of the carboniferous system, in which very important coal fields

occur. A larger but shallower basin of carboniferous rocks also

occurs in Xew Brunswick. The other mineral products of this area are

copper, gold, sulphur, gypsum, oil, gas, sandstones, limestones,

clays, and building and ornamental stones of various kinds.

The next important physiographic unit is the

ancient belted coastal plain which now forms the St. Lawrence

drainage basin (the

St. Lawrence basin).

It extends from the city of Quebec to Lake Huron, and includes the

St. Lawrence lowland in the vicinity of Montreal, and the lowland

areas in the province of Ontario, adjacent to the great lakes. This

region is underlain by Palaeozoic sediments-, limestones,

sandstones, and shales. Its mineral products are salt, gypsum,

natural gas, petroleum, building stones, brick clays, and the raw

materials of various cements, limes, and mortars. This section is

one of the most populous areas in Canada, and. although essentially

an agricultural area, a very considerable percentage of the people

are connected with the industries which arise through the occurrence

of these natural products.

Westward of the Laurentian plateau, from the

city of Winnipeg and Lake Winnipeg, we have the

Great Plains area, or the

Interior Continental Plateau, extending

to the foothills of the Rocky mountains, a distance of about 000

miles. Northward from the United States boundary, at parallel 49°

X.. to the Arctic ocean, is a distance of about 1000 miles. This

area includes two great river basins: the Saskatchewan basin on the

south, and the Mackenzie basin on the north, the divide between them

lying not far from 50° N. latitude. The entire area is underlaid by

sedimentary strata, ranging in age from early Palaeozoic to later

Mesozoic. The southern part of the area, including the greater

portion of the Saskatchewan basin, forms the great

wheat raising districts of Canada. While it is

by no means all occupied, the country is dotted with small towns and

settlements, and is traversed by numerous railways and their branch

lines, including three transcontinental systems. The northern part

of the area, including nearly the whole of the Mackenzie basin, is

only partially explored, and contains very few inhabitants.

The southern parts produce natural gas, building

stones, and the raw materials for cements and mortars. The northern

part is known to contain deposits of rock salt, gypsum, coal, and

tar sands, and it will also produce natural gas, and, probably,

petroleum. The stream beds along the western edge of the area

contain immense gravel deposits washed down from the mountains, some

of which are known to be auriferous. The most important mineral

product of the area, however, is lignite coal, which occurs very

widely distributed over the western portion of the area, and

especially in the southern parts; many of the seams are quite thick,

and the deposits form an exceedingly important source of fuel for

the western provinces of Canada.

The mountain belt of British Columbia and the

Yukon constitute the next great physiographic unit. This is the

northern portion of the great Cordilleran belt, which extends along

the whole western side of the North American continent, from Central

America to Alaska. The Canadian portion of the belt is about 1300

miles in length. On the eastern flank of this Cordilleran belt, we

have the

Rocky Mountain ranges, composed chiefly

of Palaeozoic and Mesozoic rocks. This mountain belt is particularly

important, because of the immense reserves of bituminous coal of

Cretaceous age, found in many sections of the ranges.

Westward of the Rocky mountains, lie a series of

mountain ranges, collectively designated as the

Gold ranges. They are composed of Archean

rocks, with which are associated granites and a great thickness of

older Palaeozoic beds, all much disturbed and metamorphosed.

Westward of these ranges lies a section of country with somewhat

diversified topography, which is usually described as the

Interior plateau of British Columbia. Its

width from east to west is about 100 miles; its extent from north to

south probably about 500 miles. It differs from the mountain ranges

to the east chiefly in the lack of any lofty mountain peaks; its

main elevation is about 3500 feet above sea-level. The plateau has

been the seat of much volcanic action during Miocene times.

Beyond the plateau to the north the whole width

of the Cordillera appears to be mountainous, about as far as the

59th parallel of latitude. Still farther north the ranges decline or

diverge, and in the basin of the upper Yukon rolling or nearly flat

land, at moderate elevations, again begins to occupy wide

intervening tracts.

The western border of the Gordillera, along the

Pacific coast, is formed by the

Coast range. This range runs northward

from near the estuary of the Fraser river to beyond the head of Lynn

canal. It has a breadth of about 100 miles. It consists largely of

granite batholiths. on the margins of which occur highly altered

Palaeozoic sediments.

Beyond the coast range, near the edge of the

continental plateau, a partly submerged range of mountain- forms

Vancouver island and the Queen Charlotte islands. The rocks resemble

those of the Coast range; but include also masses of Triassic and

Cretaceous strata, which have participated in the folding. Lat'-r

Miocene and Pliocene beds occur along some parts of the shores.

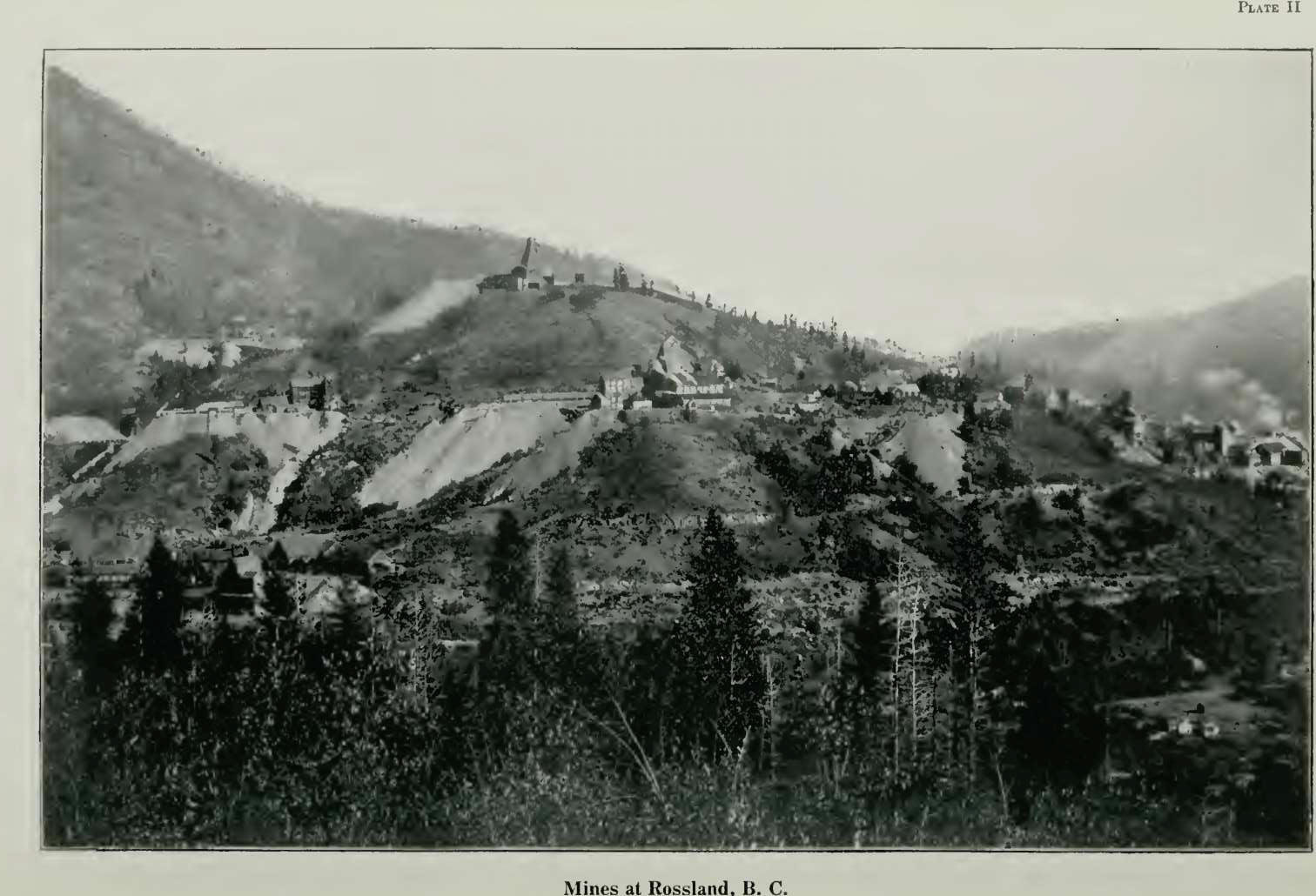

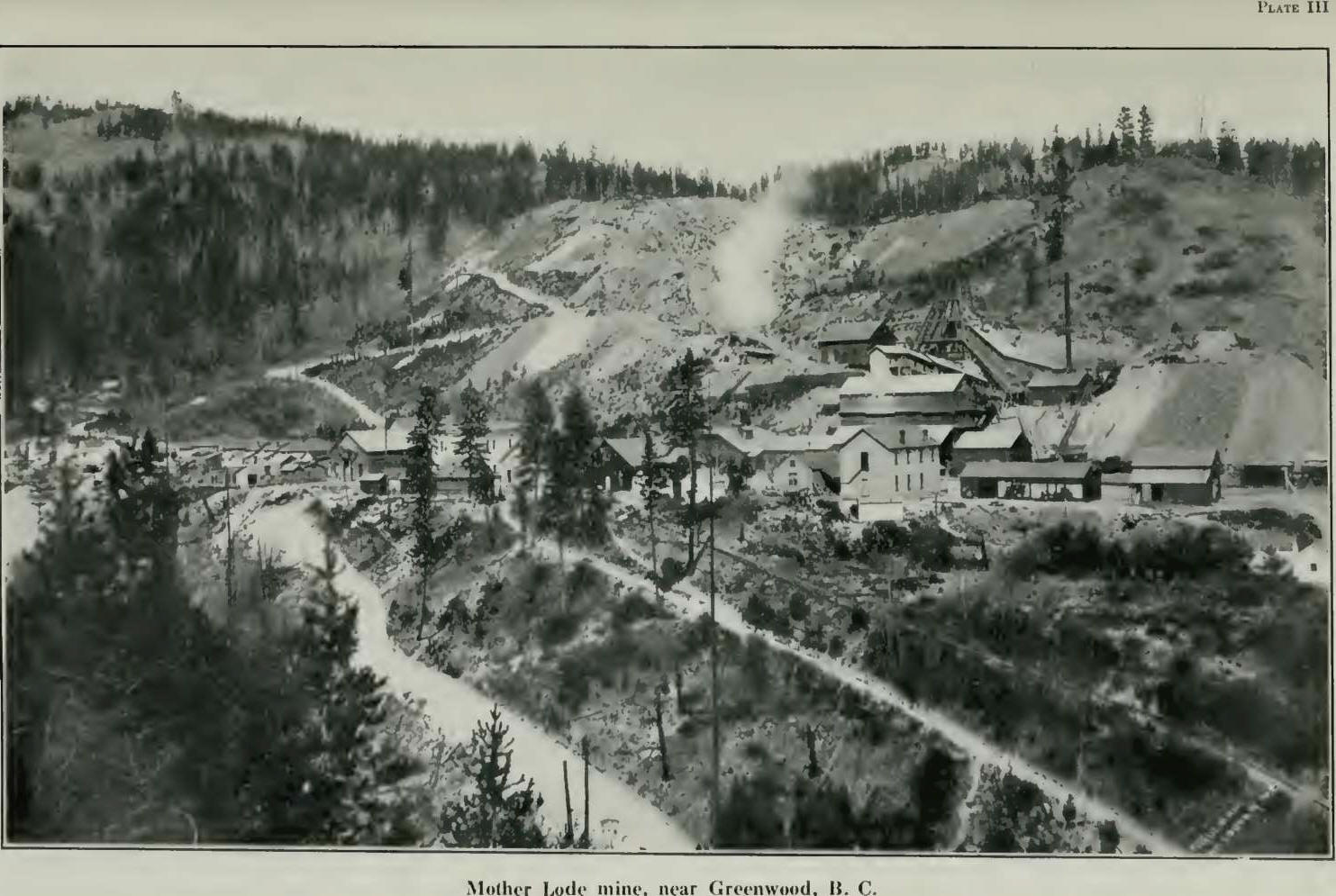

The Cordilleran belt of America is noted for its

important deposits of economic minerals, especially silver, gold,

and copper. In western Canada, it contains important copper,

copper-gold, and silver deposits; and large returns have also been

obtained from gold bearing gravels. Reference has already been made

to the Cretaceous coal deposits of the eastern part of the belt.

Similar deposits of Cretaceous age occur on Vancouver island, and

have been for many years the most important source of fuel on the

Pacific coast.

The Cordilleran region of Canada, when fully

explored, is, undoubtedly, destined to become one of the most

important mining sections of the world.

The following tabulated statement shows the

mineral production in Canada according to the published records of

the Division of Mineral Resources and Statistics of the Mines

Branch. The plantities of metals shown include not only the product

of refineries, etc., which is comparatively small, but also the

metals contained in smelter products produced and the metals

estimated as recovered from ores produced and shipped outside of

Canada for treatment.

The metals are valued for statistical purposes

at the market value of the refined product.

Non-metallic

products are valued as shipped from the mines. The ton of 2,000 lbs.

is used throughout.

A record of the production in each of the

provinces will be found at the end of the report. |