|

WELL, what is a

snowdrift? The doctor may say it is the grave of a dead snowstorm. The

poet will tell you that it is the downy bed in which the storm-king puts

to rest his sleeping children. The thin-blooded rheumatic will say it is

that which gives him the heaviest chills and the sharpest pains. The

wash-woman will declare the snowdrift gives her nice soft water long

after the sunny days of spring have melted the snow off the buildings

and the fields. If you ask the mischief-loving boy, that stands peering

through the fence, and making faces at that other boy that pretends to

be hoeing the corn, he will turn and look at you and then give his

suspenders a hitch and say, “I like snowdrifts, I do. It is that that

gives me the last snowball of the season, and it allows me to take all

that remains of itself to wash the faces of Molly and Jennie, as they go

tripping to the woods to gather the April flowers. Yes, I like

snowdrifts.’' The snowdrift, like almost everything in this world,has

its friends and its foes. The aspect of a snowdrift is affected by the

standpoint from which it is viewed. To contemplate it from the inside of

a comfortable room, with the thermometer ranging among the sixties,

gives rather pleasant ideas of it. But to one wading up to his middle in

it, with the thermometer down to ten below zero, there will not be much

enjoyment. In the one case there is a feeling of security mingled with a

sense of the beautiful. In the other there is a sense of increasing

weariness along with the consciousness of possible danger. Few things

have a prettier look than a grand drift of pure white snow on a bright

sunny day. The glistening brightness that dazzles out in all directions

might lead an inexperienced beholder to imagine that it was a thing of

more than summer warmth. But to the experienced eye it has a different

look. To such the impression made is, that however striking and pretty

the thing may be, as an object of sight, it is, after all, like the

oration of Bob Ingersoll at his brother’s funeral—very brilliant, but

very cold.

I know something of snowdrifts, both by theory and by practical

experience. Theoretically, it is simply congealed water that has been

carried by the wind and left in a convenient place till spring comes.

Then it is ready to do its part in getting up a flood to take away

somebody’s bridge or break up someone’s mill dam. Practically, it is

like the cold looks and freezing tones of some people in the world—a

good thing to keep away from, unless one had a high fever and would be

the better of a little cooling.

Some of my experiences with snowdrifts were of a character calculated to

wake up a man’s energy if he had any of that quality that is so

necessary to winter life in many parts of Canada. Others were sometimes

a little risky. But I never was much injured, though I was often

incommoded by coming in contact with them. It was during my four years’

travel on the district that I found most difficulties with them. I had

often to meet appointments twenty or thirty miles distant from each

other, and bad roads and stormy weather were not valid excuses for

failing to meet them. I never missed an appointment on account of roads

or weather. But sometimes I had hard work to get to them.

A Day of Needless Fears.

I found myself one time in the town of Kincardine. On Monday, after the

Quarterly Meeting, it began to snow and drift, and for three days and

nights the storm raged with relentless fury. My next work was at

Invcrmay. This was forty miles distant from where I was. The snow piled

up and filled the roadways from fence to fence. The Port Elgin stage did

not come on Wednesday nor Thursday, so that there was no mail from the

north for two days.

On Friday morning I started out from James Ballantine’s, telling him

that if I could not go through I would come back. It was still blowing a

gale, but the snow had ceased to fall. When I sot out of the town and

reached the Saugeen road that runs north from Kincardine to Port Elgin,

I soon found that the storm had overdone its work. The snow being a

little damp, it was so packed by the wind that for a good deal of the

way a horse could walk on the top of the drift, and not sink deeper than

to the fetlocks, and the cutter did not sink the thickness of the

runners.

But I also found that when the horse did go down it was no child’s play

to get him up again. In his efforts to get up he was almost sure to get

one of the shafts over his back. Then I must unhitch and draw the cutter

away so that he could get up. This I did a number of times that day. But

all day present difficulties did not trouble me so much as the dread of

one that I imagined was before me. Three miles from Port Elgin the road

consists of a deep cut through one of those gravel-hills so common in

some parts of the country. If that cut should be filled with show it

would present an impassable barrier in the way of further progress. My

great anxiety was to reach that place before dark. To do that I drove

all day without stopping, except to give my horse a pail of water at

noon. About dusk I came to the scene of my expected trouble. To my

surprise I saw that all my fears had been utterly groundless. There was

not a drift to be seen. The same wind that left such heavy piles of snow

in other places, had carried it through the cut. I was reminded of the

advice given by some one, which is, “ Never cross a river till you come

to it.” I made up my mind that in future I would not wallow through a

snowdrift till I reached it. About seven in the evening I got to Port

Elgin and went to old Mr. Bricker’s for the night.

Over Covered Fences.

Next morning after my day of groundless anxiety, I started in good time

for Invermay. I had to go a long way around, as the shortest road was

said to be entirely blocked up. I started out a little behind the stage.

I had gone but a short distance when the track went into the fields and

continued for nearly two miles over fences, and through door-yards, and

barn-yards, until I began to wonder if all the fences had been burned

up, as they were nearly all entirely hidden from sight. The road to

Invermay was a crooked one. As I went on I found that the track was

better broken, until I left the main road. Then there was no track at

all since the storm, and I had eight miles yet to go. However, I reached

Invermay and drove up to the house of J. \V. Dunn just as the members of

the Official Board had organized for business under the impression that

the presiding elder was somewhere stuck in the snowbanks.

A Four-Mile Drift.

On the tableland between the valleys of the Bighead ‘ and Beaver Rivers

there is a splendid piece of farming country; but any one who has

travelled over this territory, along the fourth line of the township of

Euphrasia, in the winter time, will agree with me that it is a wonderful

place for snowdrifts.

The distance from “Grier’s Rock” to the margin of “Queen’s Valley ” is

about four miles. On both sides of the road there are clearings all the

way. I have often seen this roadway full from side to side, so that the

fences were covered in and in many places entirely out of sight. Teams

going in opposite directions can pass each other only at the gates of

the farmhouses. When two teams are meeting, the one that comes to a gate

first must stop and wait for the other to come up. I have had many a

tussle with the drifts as I went from Meaford to my work south of there.

On one occasion I was going up the hill at Griersville. The road is cut

down into the rock thirty feet or more, and only wide enough for two

teams to pass. There had been a heavy snowstorm, and the road was filled

up on one side ten or twelve feet deep, so the top of the snow looked

like one side of a steep roof.

As I was going up my horse got off the beaten track and into the

unpacked snow on the lower side. He rolled over on his back and turned

the cutter upside down. When he stopped rolling he was lying in the

acute angle where the inclined plane at the top of the snowdrift met the

perpendicular wall of craggy rocks. I only escaped being in the same

position with the cutter on top of me by throwing myself out on the

upper side as it was going over. When I got on my feet and saw the

condition of things, I concluded the commercial value of my horse at

that moment was an unknown quantity. If he commenced to struggle he

would be almost sure to knock his head to pieces against the sharp

corners of the rocks. I saw that the only chance was to keep him still

as he was until help should come along from some direction. I got to his

head and by caressing and talking to him I managed to keep him pretty

still. It was not long before I saw teams coming. A lot of men and some

women were in the sleighs. When they came to the foot of the hill the

men left their teams in the care of the women, and came to help me.

Shovels were got and the snow dug away, so that in a little while all

was right again. After all was over an old farmer by the name of

Abercrombie said to me, “ Sir, when I came up and saw the fix your horse

was in I would not have given fifty cents for his life. He is the

coolest horse that I ever saw in trouble, and you are the coolest man

that I ever saw have an animal in danger.” I said to him, “ You must

remember that coolness is catching. The man that keeps himself cool can

generally control his horse.” No harm was done only in the loss of time.

Missing the Way.

I was once going from Singhampton to Horning’s Mills in the middle of

winter. I had my daughter Anna with me. The roads were badly drifted. We

had not gone far from Singhampton when we came to a place where the snow

was piled up from six to eight feet on the roadbed. On one side was a

piece of bush. The horse soon got down in the snow. I took the girl and

carried her oil the drift and set her down by the root of a tree, while

I got the horse and cutter down from the pathless ridge of snow in which

they were partially covered over. I led the horse over old logs and

fallen trees for a distance of twenty or thirty rods till we came to a

clearing; then we went across two farms, throwing down the fences in our

way. At last we came into a barnyard, where we found a man feeding

stock. He told us that we had missed our way and had been on a road that

had not been used for some time. He put us on a better road, where a

track had been broken through the fields, out to another line where

there was more travel.

After we had gone a few miles we came in sight of a man and team with a

load of saw-logs. The road was very sidelong where he was. All at once

the load capsized, and the one horse fell and the other rolled clear

over it, so that the near horse was on the off side and both were lying

on their backs with their legs flying in the air like drum-sticks. When

we came to the place I let the girl hold my horse and went to help the

man. The horses were very restless, and their owner was somewhat

frightened. Two men came from the opposite direction, and with their

help we soon got the horses on their feet. On a close examination it was

found that not a cut or scratch could be seen about them. The man stood

and looked at the horses and then at the sleigh for a few moments; then

he began to swear like a drunken sailor. After a little I said to him,

“My friend, that is a queer way of returning thanks for the safety of

your property.” He answered, “Well, I know it is not just the thing, but

sometimes when a fellow don’t know whether to laugh or cry it seems

easier to swear than to do either.” We soon got to the parsonage at

Horning’s Mills, and put up for the night with Mr. Will, who was then

stationed there.

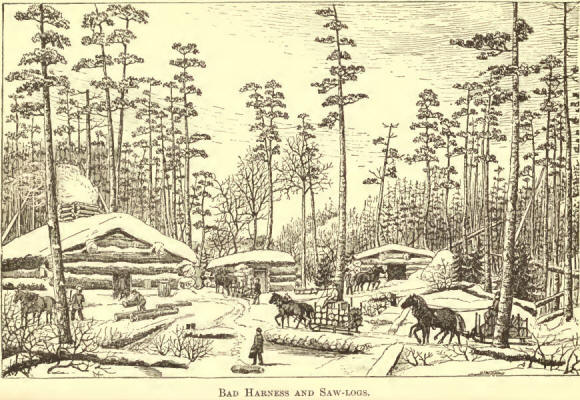

Bad Harness and Saw-logs.

The next day was very cold and clear. In going through the township of

Amaranth we overtook a man with a load of saw-logs. He had a good team

and a heavy load, but his harness was old and rotten. The road was

drifted full from fence to fence, and the beaten track was a succession

of ridges and hollows. In drawing the load out of one of the

“pitch-holes” the horses broke their harness. When we came up to the

place I saw that there was no chance of getting past until we got to a

cross-road fifty or sixty rods ahead.

I never did like to pass anyone on the road, and not try to help him, if

he was in trouble. But in this case I could not have done so if I would.

Again I gave my daughter the lines and went to help the man. His trouble

now became mine as well as his. While he toggled up the harness, I got

some rails from the fences and fixed them as pries to help lift the load

out of the hollow. After several attempts we succeeded. But we had gone

but a few rods when another difficulty met us. The road became so

sideling that there was great danger of the load turning upside down, as

was done the day before. To prevent this we took a fence rail and made a

temporary lever of it by fastening one end of it to the lower side of

the sleigh, while the other end reached out some ten feet into the road

on the upper side, the rail being placed crosswise of the road. On the

end of the lever I perched myself like a squirrel on a limb. The driver

stood on the upper side of the load and managed the team. We found by

one riding on a sleigh-rail and the other on a fence-rail, we could keep

the load right-side up. We got to the cross-road, and I drove on and

left the man with the bad harness to himself.

Soon after we came to Mr. James Johnston’s in Garafraxa. When we went

into the house, Mrs. Johnston assisted my daughter in taking off her

wraps. She found that both of her ears were frozen as hard as a piece of

sole-leather. She had neglected to attend to herself while looking after

the horse. When I asked her if she did not know that her ears were

freezing, she said: “I felt them getting very cold, but I did not say

anything, for I thought there was trouble enough just then without me

making matters worse by complaining.” She was one of the uncomplaining

kind. But now she is where frozen ears and chilled bodies are unknown,

safe in the home beyond the tide.

Snowdrifts Versus Wedding Bells.

Twelve miles south of the town of Meaford is the home of the Gilray

family. One of the daughters of Mr. and Mrs. Gilray was to be married on

a certain day to a young man living in Meaford. I was engaged to perform

the ceremony, assisted by a brother of the bride, Rev. A. Gilray, who

lived in Toronto. Two days before the day of the wedding was one

continued snowstorm. The roads were badly drifted before, but the

addition of two days’ steady snowing and drifting made them almost

impassable. Knowing all about the “four-mile drift” on the fourth line

of Euphrasia, I did not attempt to go by that road. But, instead, I went

by Thornbury, and up the valley of the Beaver River. This was nearly

twice as far, but it was not so much drifted. By starting early I

reached the place in good time.

When I arrived neither the groom nor the Rev. Mr. Gilrav had reached the

place. The hour fixed upon for the ceremony came. A number of guests

assembled, but nothing was seen or heard of the expected parties.

Meanwhile the would-be son-in-law and a few select friends were

floundering in the drifts of the “beautiful” that impeded their

movements. They soon became aware of the fact that time was flying,

while they were going at a snail's pace. Old Time relentlessly refused

to wait, even for a wedding party. And the thought that the swift-winged

hours, as they sped on in their unchecked career, seemed to mock the

slowness of the anxious plodders through the snow, was almost enough to

drive an ardent lover and an expectant bridegroom out of his senses. But

Mr. D. Youmans was not the sort of a man to be thrown into despair by a

little delay, but no doubt he would have been pleased to send a short

message to Agnes, saying, “I am coming,” if he could.

At last, after long hours of delay, the party arrived at the old

homestead, where a lovely, blushing bride-elect awaited one of them, and

the best productions of the farm and the grandest achievements of the

culinary art were ready for the whole of them.

But the unpleasant moments of suspense were still to be prolonged. The

reverend brother had not yet made his appearance, and every one felt

that to proceed without him would be about as unpleasant as it would be

for a farmer to bind up a sheaf with a handful of nettles. After waiting

another hour a sort of council was held and the conclusion come to was

to the effect that either i\lr. Gilray had been detained in the city, or

else the train in which he travelled was blockaded in the drift

somewhere. After due deliberation, it was decided to go on. with the

ceremony. We did so, and just as we came to the conclusion of it, Mr.

Gilray came in, just in time to join in the congratulations. It was an

awkward moment. We all regretted the affair. It would have been

difficult for any of us to tell, at that moment, whether congratulations

for the happy couple, or commiseration for the disappointed brother,

were uppermost in our mind. But all concerned accepted the situation

with as good a grace as possible. No one was censured, for no one was to

blame. Years afterward I met Mr. Gilray in the village of Streetsville,

where 1 went to hear him lecture. We had some talk about old times, and

among other things mention was made of his coming too late to the

wedding.

A Day to be Remembered.

One morning I started from Mount Forest to Mea-ford. The mercury was

about twenty degrees below zero. I had no idea that it was so cold until

I was on the road. When I got to the town of Durham, I turned east

towards Priceville and Flesherton. About four miles from Durham, I came

up to a lot of children on their way home from school.

Among them were two little midgets that were crying piteously as I came

to them. A half-grown girl and a big boy were trying to help them along.

I stopped and enquired what ailed the little ones. I was told that they

were freezing. I also learned that their homes were one and a-half miles

ahead. I said, “It seems to me that their mothers acted very

thoughtlessly to send such small children so far on such a day.” The

answer that I received was, that in the morning they got a ride to the

school, and their mothers did not think it was so cold.

I filled my cutter box full of the smallest of the children. The two

little girls being my special care, I covered them all up with the robes

and drove on. Soon the crying ceased. In a little while everything was

changed. Instead of sighs and whimpers there was laughing and singing.

Before parting with my little friends, I had the most cheery and jolly

load of juvenile humanity that it had ever been my lot to carry.

When we came to the place where I had been directed to let the children

off, they scattered in different directions, and scampered to their

homes. I went on feeling more pleasure than I should if I had conferred

a favor on the greatest man in the country. The day was so intensely

cold that when I got to Priceville, I was so nearly frozen that I was

forced to stop at the hotel and warm. That was a thing that I had never

done before, nor have I done it since. I could stand it as far as a

horse ought to go without feed any day in the year, but that day was too

much for me.

Teamsters Badly Beaten.

From the Black Horse Corners in Kinloss, I once drove to Paisley and

Invermay, through one of the worst snowstorms that I have ever seen. The

snow was deep before, but it had now been storming furiously for

twenty-four hours, with no signs of an abatement. I started about eight

in the morning. The storm came from the north-east, so that I had to

face it. Nobody was on the road. I only met a man and a dog on the road

that day. At that time there was a great deal of teaming of salt and

lumber on the old Durham road. In going twelve miles that day, I passed

eight loads of salt and nine loads of lumber that had been left sticking

in the drift, while the teamsters had found shelter for themselves and

their horses in the houses and stables of farmers along the road until

the storm should cease.

When I reached the Flora and Saugeen road, I thought it somewhat strange

that on such a leading thoroughfare I could see no symptoms of a beaten

track; but so it was. However, I turned north and after a hard tussle

with the immeasurable heaps of snow that covered the road in some places

to the depth of nine or ten feet, I reached the corner at the “Dutch

Tavern.” Here I had intended to get my dinner and feed my horse; but I

went in and looked around a little. I came to the conclusion that if the

kitchen and dining-room were any relation to the bar-room I would not be

able to eat much. So I got some oats and fed my horse, and went without

my dinner. I found here three men and a couple of women and two span of

horses blockaded by the storm. They were going to Ainleyville, now

called Brussels, and the road that I had just passed over was the way

they wanted to go. On my telling which way I came, the landlord told me

that the road had been abandoned two weeks before on account of drifts,

and the teams, including the stage, had gone another way; but the

blockaded travellers took courage and started on their way. They said if

one man and one horse could come through, surely three men and four

horses ought to go through. I told them they could do it if they made up

their minds to go through.

Before they started, one of them proposed to give three cheers for the

old man who had made a track for them. I told him to keep his cheers,

for he would need all of them before he reached the next corners, a mile

and a-quarter ahead. I do not know how they got along, as I started one

way and they the other.

I reached Paisley at seven p.m., and stopped at a hotel, got a good

supper, went to bed, and after a comfortable night, got breakfast and

then wallowed through the drifts to Invermay, which was eighteen miles

distant. I got there in time for the Quarterly Meeting.

The Will Makes a Way.

From Listowel to Mount Forest there was no great amount of travel at the

time that I was presiding elder of the Huron District. In the winter it

was often very difficult to go from one place to the other. On one

occasion I started from Listowel after a heavy storm of snow and drift.

When I got to where Palmerston now is, I turned north towards Ilarriston

in the township of Minto.

The track here was entirely hidden b}7 the recent fall of snow. It

looked as if there was no beaten road ; but my horse was accustomed to

snowdrifts, and by letting him take his own way he would keep on the

track pretty well. When I had gone about half a mile from the turn I met

two men with a horse and a broken cutter. They were both walking. One

was leading the horse and the other going ahead and making a track; but

instead of being on the road they were dodging in and out of the fence

corners. I at once made up my mind that they were city gents who knew

but little about driving borses in deep snow.

When I came up one of them spoke to me and said, “I say, old man, where

are you trying to go?”

“Well, sir,” I answered, “I am intending to go to Mount Forest by way of

Harriston.”

He replied, “You may just as well turn back, for you cannot go through.”

“What makes you think so?” I asked.

“We have just come from there and know all about it,” was his answer.

“Well, sir,” I said, “I am an old man, as you can see; I have gone

through a great many snowdrifts in my time, and I have never yet turned

back on account of supposed difficulties before me.”

“There is nothing like a determined will,” said the stranger. “Go ahead

and perhaps you will get along all right.”

“Sir,” said I, “somewhere I have read that a good motto is found in.

this, ‘Go as far as you can, either find a track or make one,’ and I

know of no place where this applies with greater force than in going

through snowbanks.”

We parted, and I went on my way and they on theirs.

A Message that Never Was Sent.

When I was a boy I got into the habit of saying “ I. can’t ” when I was

told to do anything, no matter how easy it might be to do it. My mother

often tried to break me off the habit, but she failed in doing so.

One day I was going with my father to the barn. Beside the path lay a

stick of firewood about a foot thick and thirty feet long. My father had

in his hand a switch that he picked up as he was coming along. When we

came to the log he told me to take hold of the end of it and lift it. As

usual, I said, “I can’t,” but before the words were fairly spoken he

gave me three or four cuts across the shoulders with the whip that made

me wince. “Now,” said he, “just take hold and try to lift it, or you

will get more of this,” shaking the switch at me. I took hold of it, and

to my utter astonishment lifted the end a foot or more from the ground.

The secret of this was found in the fact that a stone was under the log

near the middle, so that the ends nearly balanced. Whether this was by

design or otherwise I never knew, but it furnished my father an

opportunity to give me a lesson that has been of use to me in more ways

than one.

One winter I found myself at Orangeville Quarterly Meeting, after an

absence from home of over four weeks. Saturday and Sunday were very

stormy. On Monday morning the storm was still raging, with no appearance

of cessation. I had intended to start for home that morning. I was

staying at Mr. Abiathar Wilcox’s, about half a mile from the village.

The day was so rough and the roads so badly blocked up that I concluded

to take the advice of this kind family and not attempt to go until the

storm was over and the roads opened.

I wrote a copy of a telegram to send home in these words: “Stormbound at

Orangeville; home when storm ceases; quite well.” With this in my pocket

1 started to the telegraph office. When going through the gate at the

road I recalled the counsel of my father after I lifted the end of the

log, which was, “Never say you can’t until you try.” I turned back and

went to the stable and harnessed my horse, and in less than ten minutes

was on the road. After a three days’ battle with snowdrifts I got home

to Meaford in safety with the message that never was sent still in my

pocket.

A Frost-bitten Official.

From the “Black Horse” Corners in Kinloss to Kincardine on Lake Huron is

twelve miles. In the winter time this is frequently “a hard road to

travel.” With the mercury below zero, and the wind going from forty to

fifty miles an hour, persons facing toward the lake need to be well clad

or they will suffer from the cold; and even then “Jack Frost” will

sometimes steal through unsuspected openings in their habiliments and

leave his icy touch on their ears or cheeks or noses.

On one occasion the Rev. J. M. Simpson, who was then presiding elder,

and myself, had been holding missionary meetings at Kinlough and Kinloss.

We had a stormy night at the latter place, so that very few came out to

the meeting. We put up for the night with Mr. and Mrs. John Hodgins.

When we got up in the morning we found that the night had left behind it

one of the wildest days that we had ever seen. It was Saturday, and our

Quarterly Meeting at Kincardine was on the next day. There was no help

for it—we must face the storm. As we were about starting Mrs. Hodgins

said to me, “You must not freeze Mr. Simpson on that cold road. You have

been over it so often that you have got used to it.” I replied that he

had only one to look after, while I had two—myself and horse.

We started out about 10 a.m., and of all the days that I have ever

experienced that was one of the worst. When we got about half way I

asked Mr. Simpson if he was cold. He said he was not, and we went on. As

we came nearer the lake the storm seemed more severe. We both got cold,

and concluded to stop at the house of Henry Daniels and warm, but when

we came to his gate it was entirely snowed up. Then we thought to go on

and stop at William Purdy’s on the next side line, but the snow was so

blinding that we passed that without seeing it. We concluded that we

were a lone: while in reaching the side line, but when we found where we

were it was inside the corporation of Kincardine and almost home.

Next morning when I met Simpson I could not keep my face straight while

I looked at him. His face had the most comical appearance of anything

that I had seen of the kind. Wherever the frozen snow had touched, it

had left a mark. His face looked as though some one had taken the skin

of an Indian and cut it into round pieces ranging from five to fifty

cents in size, and stuck them on in grand confusion all over it from top

to bottom. When I had laughed at him for a while, he asked me if I had

looked into the glass yet since we came home. When I did so I found that

I had been making merry at my own likeness, for my face was about as

spotted as his. I had been doing what people often do, namely, criticise

in others what is most like in themselves. Some of the people said that

we were queer looking specimens of clerical dignity and official

importance. |