|

Monzie

Castle is situated on the very edge of the Highland line midway between

Crieff and the mouth of the Sma’ Glen. The Campbells acquired the fourth

part of Monzie when Archibald son of Cohn Campbell of Glenorchy married

Margaret Toshoch eldest daughter of Andrew Toshoch of Monzie in 1581.

Archibald then sold these lands to his brother, Black Duncan of Glenorchy,

who in turn granted them to his son, another Archibald.1 As the

papers in this collection indicate Archibald was followed by his son Duncan

who died debt-ridden to be succeeded by his nephew Patrick, an individual

similarly plagued with financial troubles. Patrick’s son Cohn received a

charter of the lands of Monzie from Charles II. Cohn was in turn succeeded

by his son Patrick Lord Monzie an advocate, member of the Court of Session2

and the subject of many of the documents of this collection.

Glenorchy’s

acquisition of Monzie occurred at a period of spectacular Campbell

aggrandisement.3 Monzie, on the banks of the Shaggie Burn, was a

fertile spot as its Gaelic derivation Magh-eadh - ‘plain of corn’ -

indicates. During the eighteenth century, in the days of the great cattle

droves, thousands of head of cattle passed through the community on their

way to the trysts at Crieff. The Toshoch family into which Archibald married

derived its name from Gaelic toiseach ‘chief’ or anglice

‘thane’, the true clan name being Menzies.

Just how

the present collection came into existence is unknown. It was presented to

the university through the generosity of Dr. A.I. MacRae but the surviving

documents must represent only a small portion of what were once the Monzie

muniments. They span the period from 1416 to 1811 but owing to their

heterogeneous character only the merest indication of their range and

content is possible here.

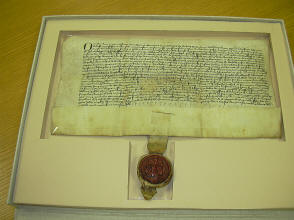

It was

through the Menzies connection that the earliest and most interesting pieces

found their way into the collection. The oldest document in the University

of Guelph Library’s Archival Collections is a letter of Henry Sinclair, Earl

of Orkney, appointing David Menzies tutor testamentary to his heirs,

especially William, and naming Menzies governor of his men, lands, rents,

possessions and goods in Orkney until his heirs attained their majority.

Several other documents, including an indenture between Menzies and the

earl, are associated with this transaction. In a study illustrative of that

field of historiography known as speculative coincidence Frederick J. Pohl4

has argued that Earl Henry’s father and namesake led an expedition to Nova

Scotia in or around 1398. The explorer died c.l400. His successor was

captured at the battle of Homildon Hill in 1402. He enlarged his spectacular

castle at Roslin south of Edinburgh and greatly improved his estates. He was

entrusted with the task of escorting young Prince James to safety in France

in 1406 when their ship was captured by English pirates who promptly

delivered the prince, shortly to succeed as James I, to an eighteen year

imprisonment in the Tower of London. Earl Henry was soon released and he

acted on several occasions on behalf of his captured king. He issued his

letter to Menzies on 16 December 1416. Earlier that year he received a safe

conduct to travel to England which may explain why he felt compelled to make

arrangements for the well-being of his heirs.5

Sir David

Menzies (1377-1449), also known as Saint David Menzies of Weem because he

took holy orders later in life, was Earl Henry’s brother-in-law. He governed

Orkney until 1423 when he became a hostage for the payment of James I’s

ransom. It is of interest to note that a copy of the document under

discussion was extant in the charter room at Castle Menzies c.1750.6

It has not been seen since. Hence the Guelph letter is, to the best of our

knowledge, unique.

The

collection contains a number of assignments and discharges of rather

technical and local interest and dated in the main to the reigns of James VI

and Charles I. Many of these concern the domestic affairs of the Campbells

and various land transactions. There is one royal letter (1592), a notarial

instrument, a band, several financial accounts and a letter of Andrew Murray

Lord Balvaird discussing Scotland’s predicament in 1643 in the heady months

leading up to the signing of the Solemn League and Covenant.

As might be

expected, the Monzie papers contain a useful selection of estate rentals the

main interest of which derives from their illustration of pre-improvement

tenancy. The rentals preserve the names of tenants on the Monzie estates,

the names and extent of their holdings measured in acres and ploughgates

together with numerous details about the rents paid in cash or kind. There

is information about the quantities of meal and bear (an inferior barley)

produced as well as the conversion prices and the numbers of livestock,

mainly sheep and poultry. Later eighteenth century rentals such as that for

Innerpeffray (1751) show clear evidence of agricultural improvement.

A sizeable

section of the collection concerns the career of Patrick Lord Monzie.

Patrick was appointed to the Equivalent Company in 1728 which was set up to

administer the ‘Equivalent’, that sum of money - almost 400,000 pounds -

granted by the English parliament in terms of the Treaty of Union in 1707 to

compensate shareholders in the abortive Darien Scheme of the 1690s. Patrick

acquired the dead stock debts and effects of the African Company, as it was

called, since although the one disastrous colonial venture took place in

South America it was sponsored by the Company trading to Africa and the

Indies. Lord Monzie also acquired the house of the African Company in

Milne’s Square, Edinburgh, built between 1684 and 1688 by Robert Myhie,

master mason to four monarchs from the reign of Charles II to that of Queen

Anne. Several documents provide illuminating insights and minute details on

the appointment of this house noting rooms, furnishings and the rest.

Patrick’s wife, Catherine, a member of the Erskine of Alva family, became

something of a celebrity in the square where in her younger days she had

been compelled to fight off the rather unsavoury advances of Lord Lovat.7

Monzie’s involvement in the African Company may have been not unconnected

with the fact that his kinsman Daniel Campbell was secretary to the Royal

Bank of Scotland.

Despite his

apparent good fortune Patrick Lord Monzie experienced lifelong financial

problems as many of his papers indicate. Apart from detailed accounts of the

African Company the collection contains much information on his personal

debts. He had territorial disputes with Campbell of Lawers. He was forever

receiving solicitations for financial assistance from the children of

friends and neighbours in Perthshire who were anxious to make their fortunes

in England or overseas. One such was Captain Robert Haldane R.N. of the

Gleneagles family temporarily in disgrace in 1754 for having grounded his

ship in Plymouth Sound.8 Even as he asked Patrick for a loan he cheerfully

admitted the use to which it might be put

‘By this time I suppose you’l begin to think I’m

lost and indeed tis true, for ever since I have been in town the devil take

me if I know how the time has slipt away what with love, what with company

claret and other diversions I’m almost fallen into the same scrape with Mr

John Carstairs the man Jamie Murray told us of that went out to ask his own

name. . .‘

When

Patrick died in 1757 he left behind some 339 bottles of wine and to judge

from a remarkable inventory drawn up after his death, almost as many beds.

His fine house in Mylne’s Square was sold. He was succeeded by Captain

Robert Campbell of Monzie who achieved the rank of colonel before his death

in 1790. His son, Lieutenant-General Alexander Campbell petitioned to have

the entail, drawn up by Cohn Campbell of Monzie in 1676, altered. Entail

permitted someone like Cohn to dictate the destination of his estates

through succession, virtually in perpetuity. It was difficult to raise

credit on entailed estates which probably accounts for Patrick’s problems.

The final document in the collection preserves Alexander’s arguments as

presented to the Court of Session.

1

Sir J.B. Paul (ed.) Scots peerage, 9 vols. (Edinburgh, 1904-14), vol.

2, pp. 183-186.

2 George Brunton (ed.), An

historical account of the Senators of the College of Justice of Scotland

(Edinburgh, 1849), pp. 501-2, 516.

3 Edward J. Cowan, “Clanship, kinship

and the Campbell acquisition of Islay”, Scottish historical review,

vol. 58, 1979; “The Angus Campbells and the origins of the Campbell-Ogilvie

feud”, Scottish studies 25, 1981.

4

Frederick J. PohI, Prince Henry Sinclair: his expedition to the New World

in

1398 (New York, 1974), passim.

5

Scots peerage, vol. 6, p. 570.

6 D.P. Menzies, The red and white

book of Menzies: the history of Clan Menzies and its Chiefs (Glasgow,

1894), pp. 100-111.

7

Wilmot Harrison, Memorable Edinburgh houses (Edinburgh, 1898), p. 19.

8

Sir J. Aylmer, L. Haldane, The Haldanes of Gleneagles (Edinburgh,

1929), pp. 184-187.

EDWARD J.

COWAN

|