|

Review in Lansdowne

Park—Princess Patricia presents the Colours—South African veterans and

reservists—Princess Patricias in the trenches—St. Eloi—Major Hamilton

Gault —A dangerous reconnaissance—Attack on a sap—A German

onslaught—Lessons from the enemy—A march to battle—Voormezeele—Death of

Colonel Farquhar— Polygone Wood—Regiment’s work admired—A move towards

Ypres—Heavily shelled—A new line—Arrival of Major Gault—Regiment sadly

reduced—Gas shells—A German rush—Major Gault wounded—Lieut. Niven in

command—A critical position—Corporal Dover’s heroism —A terrible

day—Shortage of small arms ammunition— Germans’ third attack—Enemy

repulsed—Regiment reduced to 150 rifles—Relieved—A service for the

dead—In bivouac—A trench line at Armenti&res—Regiment at full strength

again—Moved to the south—Back in billets—Princess Patricias instruct new

troops—Rejoin Canadians—A glorious record.

“Fair lord, whose name I

know not—noble it is,

I well believe, the noblest—will you wear

My favour at this tourney?”

—Tennyson.

On Sunday, August 23rd,

1914, on a grey and gloomy day, immense numbers of people assembled in

Lansdowne Park, in the City of Ottawa, to attend divine service with the

Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, and to witness the

presentation to the Battalion of the Colours which she had worked with

her own hand. The Regiment, composed very largely of South African

Veterans and Reservists, paraded with bands and pipers, and then formed

three sides of a square in front of the grand stand. Between the

Regiment and the stand were the Duchess of Connaught, Princess Patricia,

and their Ladies-in-Waiting. The Princess Patricia, on presenting the

Colours to Colonel Farquhar, the Commanding Officer of the Regiment,

said: “I have great pleasure in presenting you with these Colours which

I have worked myself; I hope they will be associated with what I believe

will be a distinguished corps; I shall follow the fortunes of you all

with the deepest interest, and I heartily wish every man good luck and a

safe return."

Not even the good

wishes of this beautiful and gracious Princess have availed to safeguard

the lives of the splendid Battalion which carried her Colours to the

battlefields of Flanders; but every member of the Battalion resolved, as

simply and as finely as the knights of mediaeval days, that he would

justify the belief in its future so proudly expressed by the lady whose

name he was honoured to bear.

It is now intended to

give some account of the fortunes of the Battalion since the day, which

seems so long ago, when with all the pride and circumstance of military

display, it received the regimental colours amid the cheers of the

citizens of Ottawa.

The Princess Patricias,

containing a far larger proportion of experienced soldiers than any

other unit in the Canadian Division, was not called upon to endure so

long a period of preparation as the rest of the Canadian Expeditionary

Force; and at the close of the year 1914 they sailed from England at a

moment when reinforcements were greatly needed in France, to strengthen

the 8oth Brigade of the 27th Division, and to take their part in a line

thinly held and very fiercely assailed. For the months of January and

February the Regiment took its turn in the trenches, learning the hard

lessons of the unpitying winter war. A considerable length of trenches

in front of the village of St. Eloi was committed to its charge. Its

machine-guns were planted upon a mound which rose abruptly from the

centre of the trenches.

The early days were

uneventful and the casualties not more than normal, although some very

valuable officers were lost. On February 28th, 1915, the Germans

completed a sap, from which the Battalion became constantly subject to

annoyance, danger, and loss. It was therefore determined by the

Battalion Commander to dispose of the menace. Major Hamilton Gault and

Lieut. Colquhoun carried out by night a dangerous reconnaissance of the

German position, and returned with much information. Lieut. Colquhoun

went out a second time, alone, to supplement it, but never returned. He

is to-day a prisoner of war in Germany.

The attack was

organised under Lieut. Crabbe; the bomb-throwers were commanded by

Lieut. Papineau. The last-named officer, a very brave soldier, is a

lineal descendant of the rebel of 1837. He is himself loyal to his

family traditions except when dangers and wars menace the Empire. At

such moments, in spite of himself, his hand flies to the sword. The

snipers were under Corporal Ross. Troops were organised in support with

shovels ready to demolish the parapet of the enemy trench.

The ground to be

traversed was short enough, for the sappers’ nearest point was only

fifteen yards from the Canadian trench. The attacking party rushed this

space and threw themselves into the sap. Corporal Ross, who was first in

the race, was killed immediately. Lieut. Crabbe then led the detachment

down the trench while Lieut. Papineau ran down the outside of the

parapet throwing bombs into the trench. Lieut. Crabbe made his way

through the trench, followed by his men, until his progress was arrested

by a barrier which the Germans had constructed.

In the meantime, troops

had occupied the rear face of the sap to guard against a counter-attack.

A platoon under Sergeant-Major Lloyd, who was killed, attacked and

demolished the enemy parapet for a considerable distance. The trench was

occupied long enough to complete the work of demolishing the parapet.

With dawn, orders were given for the attackers to withdraw, and as the

grey morning light began to break, they made their way to their own

trenches, with a difficult task well and successfully performed. Major

Gault was wounded in the course of the engagement, in which all ranks

behaved with dash and gallantry, although the men had been for six weeks

employed in trench warfare under the most depressing conditions of cold

and damp.

On March ist the enemy

made a vigorous attack on the Princess Patricias with bombs and shell

fire. Between the ist and the 6th, a fierce contest was continually

waged for the site of the sap which the Battalion had destroyed.

Sometimes the Princess Patricias defended it; sometimes the British

battalions, with whom they were brigaded and whose staunch and faithful

comrades they had become.

On March 6th, carrying

out a carefully concerted plan, our men withdrew from the trench lines,

which were still only twenty or thirty yards from the German trenches;

and our artillery, making very successful practice, obliterated the sap

and the trench which the enemy had used for the purpose of creating it.

The enemy were blown out of the forward trenches, and fragments of dead

Germans were thrown into the air, in some cases as high as sixty feet.

The bombardment was carried out with high explosive shells.

The Canadian soldier is

always adaptable, and the Battalion learned, when they captured the sap

on February 28th, that the German trenches were five feet deep with

parapets two feet high, and yet that every day they were pumped and kept

dry. This knowledge resulted in a considerable improvement in the

trenches occupied by the Regiment. The experience was welcome, for the

men had been standing in water all through the winter months and the

Regiment had suffered much from frostbite.

On March 13th, while

the Princess Patricias were in billets, the Germans, perhaps in reply to

our offensive at Neuve Chapelle, made a vigorous attack in overwhelming

numbers upon the trenches and mound at St. Eloi. The attack, which was

preceded by a heavy artillery bombardment, was successful, and it became

necessary to attempt by a counterattack to arrest any further

development.

The Battalion was

billeted in Westoutre, where, at 5.30 on March 14th, peremptory orders

were received to prepare for departure. At 7 p.m. the march was begun.

At Zevecoten the Princess Patricias met a battalion of the King’s Royal

Rifle Corps, and marched to Dickebush. At 9.30 it reached the cross

roads of Kruistraathoek. Here a short halt was made, after which the

Battalion reached Voormezeele, where it was drawn up on the roadside.

While it was in this position reports were brought in that the Germans

were advancing in large numbers towards the eastern end of Voormezeele.

The Battalion Commander, therefore, as a precaution against surprise,

detailed Number 4 Company of the Battalion to occupy the position on the

east. Soon after 2 a.m. orders were received to co-operate with a

battalion of the Rifle Brigade in an attack on the St. Eloi mound, which

had been lost early in the day. The zone of the operations of the

Battalion was to the east of the Voormezeele-Warneton road.

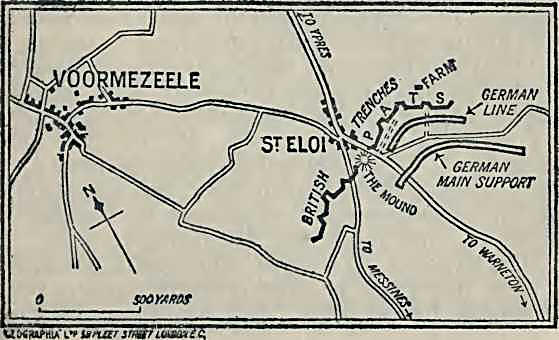

The following rough

diagram may make the position clear:—

The actual situation in

the front line was still obscure. It was known that the mound and

certain trenches to the west of it, were in German hands. It was also

known that towards the east we had lost certain trenches known to our

Intelligence Staff as P and A. It was uncertain whether the trench T was

still held by our troops. It was decided, in a matter in which certainty

was unattainable, to proceed towards a farm building which was an easily

recognised objective. This course at least promised information, for if

trench T had fallen it was certain that the Battalion would at once be

heavily attacked. If it was still intact the Battalion would, it was

hoped, cover the commencement of an assault along the German line

against trenches A and P and the mound, successively.

The alternative was to

advance southwards with the Battalion right on the Ypres-St. Eloi road.

The adoption of this plan would have meant slow progress through the

enclosures round St. Eloi, and the subsequent attack would have been

exposed to heavy flanking fire from trenches A and P.

The progress of the

Battalion was necessarily slow; the street in Voormezeele was full of

stragglers. Touch was difficult to maintain across country without

constant short halts. It was necessary always to advance with a screen

of scouts thrown out.

It was ascertained in

St. Eloi that trench A had been.retaken by British troops. This

knowledge modified the plan provisionally adopted. The Battalion altered

its objective from the farm building to a breastwork 200 yards to the

west of it. This point was reached about twenty minutes before daylight,

and an attack was immediately organised by Number 2 Company against

trench P, approaching it from the back of trench A. The attack was made

in three parties.

The advance was made

with coolness and resolution, but the attackers were met by heavy

machine-gun fire from the mound. No soldiers in the world could have

forced their way through, for the fire swept everything before it. It

was clear that no hope of a surprise existed, and to have spent another

company upon reinforcement would have been a useless and bloody

sacrifice. Three platoons were, therefore, detailed to hold the right of

the breastwork in immediate proximity to the mound, and the rest of the

Battalion was withdrawn to Voormezeele, reaching Dickebush about 8 a.m.

[Commenting on the Princess Patricias at St. Eloi, in Nelson’s “History

of the War,” Mr. John Buchan says:—“Princess Patricia’s Regiment was the

first of the overseas troops to be engaged in an action of first-rate

importance, and their deeds were a pride to the whole Empire—a pride to

be infinitely heightened by the glorious record of the Canadian Division

in the desperate battles of April. This Regiment five days later

suffered an irreparable loss in the death of its Commanding Officer,

Col, Francis Farquhar, kindest of friends, most whimsical and delightful

of comrades, and bravest of men.”]

The forces engaged

behaved with great steadiness throughout a trying and unsuccessful

night, and at daylight withdrew over open ground without Voormezeele,

reaching Dickebush about 8 a.m.

On March 20th the

Battalion sustained a severe loss in the death, by a stray bullet, of

its Commanding Officer, Colonel Farquhar. He had been Military Secretary

to the Duke of Connaught. This distinguished officer had done more for

the Battalion than it would be possible in a short chapter to record.

The Regiment, in fact, was his creation.

A strict

disciplinarian, he was nevertheless deeply beloved in an army not always

patient of discipline tactlessly asserted; he was always cheerful,

always unruffled, and always resourceful. Lieut.-Colonel H. C. Buller

succeeded him in command of the Regiment.

After the death of

Lieut.-Colonel Farquhar, the Battalion again retired to rest, and it has

not since returned to the scene of its earliest experience in trench

warfare. On April 9th it took up a line on the Polygone Wood, in the

Ypres salient, and there did its round of duty with the customary relief

in billets. By this time the men were becoming familiar with their

surroundings, and gave play to their native ingenuity. Near the trenches

they built log huts from trees in the woods, and it was a common thing

for French, Belgian, and British officers to visit the camp to admire

the work of the Regiment. Breastworks were built also behind the

trenches under cover of the woods, and the trenches themselves were

greatly improved.

The Battalion presently

moved into billets in the neighbourhood of Ypres, and on April 20th,

during the heavy bombardment of that unhappy town which preceded the

immortal stand of the Canadian Division, it was ordered to leave

billets, and on the evening of that day moved once again to the

trenches.

From April 21st and

through the following days of the second battle of Ypres the Regiment

remained in trenches some distance south and west of the trenches

occupied by the Canadian Division. They were constantly shelled with

varying intensity, and all through those critical days waited, with

evergrowing impatience, for the order that never came to take part in

the battle to the north, where their kinsmen were undergoing so cruel an

ordeal.

On May 3rd, after the

modification of the line to the north, the Battalion was withdrawn to a

subsidiary line some distance in the rear. From eight in the evening to

midnight small parties were silently withdrawn, until the trenches were

held with a rearguard of fifteen men commanded by Lieut. Lane. Rapid

fire was maintained for more than an hour, and the rear-guard then

withdrew without casualties.

On May 4th the Regiment

occupied the new line. On the morning of that day a strong enemy attack

developed. This was repulsed with considerable loss to the assailants,

and was followed by a heavy bombardment throughout the day, which

demolished several of the trenches. At night the Regiment was relieved

by the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry and withdrawn to reserve

trenches. In this unhealthy neighbourhood no place, by this time, was

safe, and on May 5th, Lieut.-Colonel Buller was unfortunate enough to

lose an eye from the splinter of a shell which exploded 100 yards away.

Major Gault arrived during the day and took over command. The Battalion

was still in high spirits, and cheered the arrival of an officer to whom

all ranks were attached.

Just after dark on the

night of May 6th, the Battalion returned to the trenches and relieved

the 2nd King’s Shropshire Light Infantry. Throughout the night, and all

the following day, it was assailed by a constant and heavy bombardment.

The roll call on the night of the 7th showed the strength of the

Battalion as 635.

The day that followed

was at once the most critical and the most costly in the history of the

Battalion. Early in the morning, particularly heavy shelling began on

the right flank, soon enfilading the fire trenches. At 5.30 it grew in

intensity, and gas shells began to fall. At the same time a number of

Germans were observed coming at the double from the hill in front of the

trench. This movement was arrested by a heavy rifle fire.

By 6 a.m. every

telephone-wire, both to the Brigade Headquarters and also to the

trenches, had been cut. All signallers, pioneers, orderlies, and

servants at Battalion Headquarters were ordered into the support

trenches, for the needs of the moment left no place for supernumeraries.

Every single Canadian upon the strength was from that time forward in

one or other of the trenches. A short and fierce struggle decided the

issue for the time being. The advance of the Germans was checked, and

those of the enemy who were not either sheltered by buildings, dead or

wounded, crawled back over the crest of the ridge to their own trenches.

By this time the enemy had two, and perhaps three, machine-guns in

adjacent buildings, and were sweeping the parapets of both the fire and

support trenches. An orderly took a note to Brigade Headquarters

informing them exactly of the situation of the Battalion.

About 7 a.m., Major

Gault, who had sustained his men by his coolness and example, was

severely hit by a shell in the left arm and thigh. It was impossible to

move him, and he lay in the trench, as did many of his wounded

companions, in great anguish but without a murmur, for over ten hours.

The command was taken

over by Lieut. Niven, the next senior officer who was still unwounded.

Heavy Howitzers using high explosives, combined with field-guns from

this moment in a most trying bombardment both on the fire and support

trenches. The fire trench on the right was blown to pieces at several

points. [The German bombardment had been so heavy since May 4th that a

wood which the Regiment had used in part for cover was completely

demolished.]

At 9 o’clock the

shelling decreased in intensity; but it was the lull before the storm,

for the enemy immediately attempted a second infantry advance. This

attack was received with undiminished resolution. A storm of machine-gun

and rifle fire checked the assailants, who were forced, after a few

indecisive moments, to retire and take cover. The Battalion accounted

for large numbers of the enemy in the course of this attack, but it

suffered seriously itself. Captain Hill, Lieuts. Martin, Triggs, and De

Bay were all wounded at this time.

At half-past nine,

Lieut. Niven established contact with the King’s Own Yorkshire Light

Infantry on the left, and with the 4th Rifle Brigade on the right. Both

were suffering heavy casualties from enfilade fire; and neither, of

course, could afford any assistance. At this time the bombardment

recommenced with great intensity. The range of our machine-guns was

taken with extreme precision. All, without exception, were buried. Those

who served them behaved with the most admirable coolness and gallantry.

Two were dug out, mounted and used again. One was actually disinterred

three times and kept in action till a shell annihilated the whole

section. Corporal Dover stuck to his gun throughout and, although

wounded, continued to discharge his duties with as much coolness as if

on parade. In the explosion that ended his ill-fated gun, he lost a leg

and an arm, and was completely buried in the debris. Conscious or

unconscious, he lay there in that condition until dusk, when he crawled

out of all that was left of the obliterated trench, and moaned for help.

Two of his comrades sprang from the support trench—by this time the fire

trench—and succeeded in carrying in his mangled and bleeding body. But

as all that remained of this brave soldier was being lowered into the

trench a bullet put an end to his sufferings. No bullet could put an end

to his glory.

At half-past ten the

left half of the right fire trench was completely destroyed; and Lieut.

Denison ordered Lieut. Clarke to withdraw the remnant of his command

into the right communicating trench. He himself, with Lieut. Lane, was

still holding all that was tenable of the right fire trench with a few

men still available for that purpose. Lieut. Edwards had been killed.

The right half of the left fire trench suffered cruelly. The trench was

blown in and the machine-gun put out of action. Sergeant Scott, and the

few survivors who still answered the call, made their way to the

communication trench, and clung tenaciously to it, until that, too, was

blown in. Lieut. Crawford, whose spirits never failed him throughout

this terrible day, was severely wounded. Captain Adamson, who was

handing out small arms ammunition, was hit in the shoulder, but

continued to work with a single arm. Sergeant-Major Fraser, who was

similarly engaged feeding the support trenches with ammunition, was

killed instantly by a bullet in the head. At this time only four

officers were left, Lieuts. Papineau, Vandenberg, Niven, and Clark, of

whom the last two began the war in the ranks.

By 12 a.m. the supply

of small arms ammunition badly needed replenishment. In this necessity

the snipers of the Battalion were most assiduous in the dangerous task

of carrying requests to the Brigade Headquarters and to the Reserve

Battalion, which was in the rear at Belle-Waarde Lake. The work was most

dangerous, for the ground which had to be covered was continually and

most heavily shelled.

From 12 a.m. to 1.30

p.m. the Battalion held on under the most desperate difficulties until a

detachment of the 4th Rifle Brigade was sent up in reinforcement. The

battered defenders of the support trench recognised old friends coming

to their aid in their moment of extreme trial, and gave them a loud

cheer as they advanced in support. Lieut. Niven placed them on the

extreme right, in order to protect the Battalion’s flanks. They remained

in line with the Canadian support trenches, protected by trees and

hedges. They also sent a machine-gun and section, which rendered

invaluable service. ,

At 2 p.m. Lieut. Niven

went with an orderly to the Headquarters, in obedience to Brigade

orders, to telephone to the General Officer Commanding the Brigade,

complete details of the situation. He returned at 2.30 p.m. The

orderlies who accompanied him both coming and going were hit by high

explosive shells.

At 3 p.m. a detachment

of the 2nd King’s Shropshire Light Infantry, who were also old comrades

in arms of the Princess Patricias, reached the support line with twenty

boxes of small arms ammunition. These were distributed, and the party

bringing them came into line as a reinforcement, occupying the left end

of the support trench. At four o’clock the support trenches were

inspected, and it was found that contact was no longer maintained with

the regiment on the left, the gap extending for fifty yards. A few men

(as many as could be spared) were placed in the gap to do the best they

could. Shortly afterwards news was brought that the battalions on the

left had been compelled to withdraw, after a stubborn resistance, to a

line of trenches a short distance in the rear.

At this moment the

Germans made their third and last attack. It was arrested by rifle fire,

although some individuals penetrated into the fire trench on the right.

At this point all the Princess Patricias had been killed, so that this

part of the trench was actually tenantless. Those who established a

footing were few in number, and they were gradually dislodged; and so

the third and last attack was routed as successfully as those which had

preceded it.

The afternoon dragged

on, the tale of casualties constantly growing; and at ten o’clock at

night, the company commanders being all dead or wounded, Lieuts. Niven

and Papineau took a roll call. It disclosed a strength of 150 rifles and

some stretcher-bearers.

At n.30 at night the

Battalion was relieved by the 3rd King’s Royal Rifle Corps. The

relieving unit helped those whom they replaced, in the last sorrowful

duty of burying those of their dead who lay in the support and

communicating trenches. Those who had fallen in the fire trenches needed

no grave, for the obliteration of their shelter had afforded a decent

burial to their bodies. Behind the damaged trenches, by the light of the

German flares and amid the unceasing rattle of musketry, relievers and

relieved combined in the last service which one soldier can render

another. Beside the open graves, with heads uncovered, all that was left

of the Regiment stood, while Lieut. Niven, holding the Colours of

Princess Patricia, battered, bloody, but still intact, tightly in his

hand, recalled all he could remember of the Church of England service

for the dead. Long after the service was over the remnant of the

Battalion stood in solemn reverie, unable it seemed to leave their

comrades, until the Colonel of the 3rd King’s Royal Rifle Corps gave

them positive orders to retire, when, led by Lieut. Papineau, they

marched back, 150 strong, to reserve trenches. On arrival they were

instructed to proceed to another part of the position, where during the

day they were shelled, and lost five killed and three wounded.

In the evening of the

ioth the Battalion furnished a carrying party of fifty men and one

officer for small arms ammunition, and delivered twenty-five boxes at

Belle-Waarde Lake. One man was killed and two wounded. It furnished also

a digging party of 100 men, under Lieut. Clarke, who constructed part of

an additional support trench.

On May 13th the

Regiment was in bivouac at the rear. The news arrived that the 4th Rifle

Brigade, their old and trusty comrades in arms, was being desperately

pressed. Asked to go to the relief, the Princess Patricias formed a

composite Battalion with the 4th King’s Royal Rifle Corps, and

successfully made the last exertion which was asked of them at this

period of the war.

On May 15th Major Pelly

arrived from England, where he had been invalided on March 15th, and

took over the command from Lieut. Niven, who, during his period of

command, had shown qualities worthy of a regimental commander of any

experience in any army in the world.

At the beginning of

June the Princess Patricias took up a trench line at Armentieres and

remained there until the end of August. In the middle of July Lieut. C.

J. T. Stewart, a brave officer who had been severely wounded in the

early days of the Spring, rejoined the Battalion. Other officers

returning after wounds, and reinforcements from Canada, brought the

Battalion up to full strength again.

Trench work and digging

then alternated with rest. About the middle of September the Battalion

moved with the 27th Division to occupy a line of trenches held by the

3rd Army in the south.

When the 27th Division

was withdrawn from this line the Princess Patricias were moved into

billets far back from the battle zone, and for a while the Battalion was

detailed to instruct troops arriving for the 3rd Army.

On November 27th, 1915,

they were once again happily reunited with the Canadian Corps after a

long separation.

Such, told purposely in

the baldest language, and without attempting any artifice in rhetoric,

is the history of Princess Patricia’s Light Infantry Regiment from the

time it reached Flanders till the present day.

Few, indeed, are left

of the men who met in Lansdowne Park to receive the regimental Colours

nearly a year ago; but those who survive, and the friends of those who

have died, may draw solace from the thought that never in the history of

arms have Soldiers more valiantly sustained the gift and trust of a

Lady. |