|

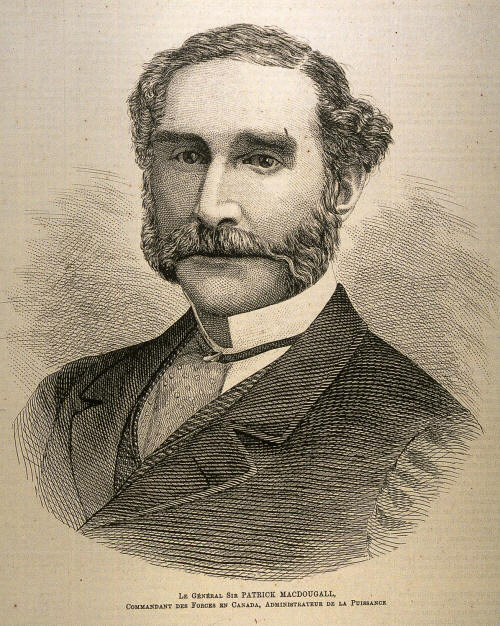

MacDOUGALL, Sir

PATRICK LEONARD, army officer, author, and dominion administrator;

b. 10 Aug. 1819 in Boulogne-sur-Mer, France, only son of Duncan

MacDougall and Anne Smelt; m. first 15 July 1844 Louisa Augusta

Napier on Guernsey; m. secondly 21 June 1860 Marianne Adelaide Miles

in Pimlico, London, England; there were no children from either

marriage; d. 28 Nov. 1894 in Kingston Hill (London), England.

Educated at a military academy in Edinburgh and the Royal Military

College in Sandhurst, Berkshire, England, Patrick Leonard MacDougall

was commissioned a second lieutenant in 1836. After serving in the

Ceylon Rifle Regiment, the 79th Foot (his father’s old regiment),

and the 36th Foot, he transferred in 1844 to the Royal Canadian

Rifle Regiment, a unit of the British army on permanent duty in the

Canadas. During ten years in Kingston and Toronto, MacDougall was

seized with the opportunities available in the North American

colonies and in 1848 he published a work which extolled the

advantages of emigration.

In March 1854 MacDougall, by then a major, was appointed

superintendent of studies at the Royal Military College in Sandhurst.

The next year he saw staff service in the Crimea and then returned

to Sandhurst, where he again turned to writing. The theory of war

(London, 1856), a précis of the writings of Napoleon and

Antoine-Henri Jomini, among others, was intended to stimulate

professional and intellectual reform within the British army, and it

was a great success. An 1857 pamphlet, The senior department of the

Royal Military College, included a call for the creation of a staff

college to institutionalize this reform, and when such a college was

authorized the same year in Camberley, MacDougall was named its

first commandant. While commandant he wrote The campaigns of

Hannibal . . . (1858).

In September 1861 MacDougall, now a colonel, left the Staff College

and went on half pay. However, when relations between Britain and

the United States soured following the Trent affair that year [see

Sir Charles Hastings Doyle*], the War Office called upon him to

suggest a scheme of defence for British North America in the event

of conflict. He was a logical choice. He had examined the problem in

1856 at Sandhurst, was an acknowledged expert in planning, and had

considerable Canadian experience. The resulting paper emphasized the

need for Britain to control the Great Lakes, hold the St Lawrence

valley, and threaten the American flank by invading Maine.

MacDougall also argued that in order to be effective the colonial

militias should be brigaded with the regular British regiments in

Canada.

Still on half pay, MacDougall travelled to Canada in 1862 and

elaborated his plans for British North American defence. He also

studied the American Civil War, but it is not known if he witnessed

any fighting. He incorporated his findings in Modern warfare as

influenced by modern artillery (1864), his first genuinely original

book on military theory, in which he concluded that rifled guns

conferred tremendous advantages on the defence. This view had great

significance for Canada, for it seemed likely that the Canadian

militia, if well entrenched, strongly supported by modern artillery,

and stiffened by British regulars, would be able to give a good

account of itself against an invading American army.

MacDougall returned to active service in May 1865 when he was

appointed adjutant general of the Canadian militia. In this position

he began to implement some of the measures and reforms he had worked

out. He drafted plans for mobilization and schemes for defence; he

urged the government to purchase reserve stores of weapons,

ammunition, and equipment; and, following the débâcle at Ridgeway

(Fort Erie), Upper Canada, in June 1866 [see Alfred Booker*], he

ordered the British garrison and the militia to train together.

MacDougall had high hopes that Canada would strengthen its defences

and that, following confederation, it might even create a small

regular army, but these hopes were dashed. With the Civil War over

and the Union army demobilizing, the United States was no longer

perceived as a threat. Moreover, Canadian politicians were arguing

that since Britain still controlled Canada’s foreign affairs, the

imperial government should pay the lion’s share of the costs of

defence. Disillusioned by the government’s lack of interest and

believing that he was of no further use, MacDougall asked to be

replaced as adjutant general, and he returned to England in April

1869. His successor was Lieutenant-Colonel Patrick Robertson-Ross*.

Reform of the British army continued to be the focal point of

MacDougall’s career. After his return to England he was a leading

figure in the implementation of the scheme of the secretary of state

for war, Edward Cardwell, for the reorganization of the army. He

headed the reserve forces from 1871 to 1873 and saw that their

training was improved, and from 1873 to 1878 he was the first

director of military intelligence at the War Office. He continued to

write. The army and its reserves (1869) foreshadowed the Cardwell

reforms in its call for a revitalization of the militia, Modern

infantry tactics (1873) analysed Prussian operations during the

Franco-German War, and periodical articles also addressed the

questions of infantry training, officer selection and education, and

tactics. None of these writings advanced radical ideas, but all

aimed at producing a British army guided by a professional ethos in

which the serious study of war was the norm.

Having been created kcmg on 30 May 1877 and lieutenant-general on 1

October, MacDougall returned to Canada in 1878, at the height of the

Anglo-Russian war scare, as commander-in-chief of the British forces

in North America. After a hectic initial period, during which he

failed to persuade the Canadian government to authorize a 10,000-man

Canadian reserve for the British army, his time at his Halifax

headquarters was uneventful. On three occasions, in 1878, 1881–82,

and 1882–83, he was administrator of the government of Canada during

the absence of the governor general. MacDougall returned to England

in 1883, retired from active service as a general in July 1885, and

lived quietly until his death in 1894. |