|

UNDER SIR JOHN AGAIN

The Mounted Police

Placed under the Department op the Interior—Experimental Farming by the

Force—Lieut.-Col. A. G. Irvine Succeeds Lieut.-Col. Macleod as

Commissioner— Difficulties with the Indians in the Southern part of the

Territories — Tribes Induced to Leave the Dancer Zone near the

International Frontier—The Establishment of the Force Increased by Two

Hundred Men.

OCTOBER 16, 1878, the

Mackenzie Government having sustained defeat at the general elections,

resigned, and the following day Sir John A. Macdonald formed a new

cabinet, taking himself the portfolio of the Department of the Interior.

That the great statesman still retained a keen personal interest in the

North-West Mounted Police was soon shown, for no later than the month of

November, the charge of the North-West Mounted Police was transferred to

the Department of the Interior, from the Department of the Secretary of

State. After this change the several branches through which the

operations of the Department of the Interior were conducted stood as

follows:—North-West Territories, District of Keewatin, Indians and

Indian Lands, Dominion Lands, Geological Survey and North-West Mounted

Police.

In his annual report

for 1879, Lieut.-Col. Macleod, the Commissioner stated:

"It will be learned

with satisfaction that the considerable influx of population into the

North-West Territories, to which I had the honour to direct attention in

my last report, has very greatly increased during the past twelve

months, and the coming season promises results far beyond anything which

has so far been experienced. The Pembina Mountain, Rock Lake, Little

Saskatchewan and Prince Albert Districts, to which the greater

proportion of the immigration of 1878 was directed, are so rapidly

becoming occupied that the stream of settlement is finding for itself

new courses, notably in the Bird's Tail ('reek district, and

south-easterly of Fort Ellice, westerly of the Little Saskatchewan, and

in the country south of the Assiniboine, in and near the valley of the

Souris River ; also in the neighborhood of the Turtle Mountains, which

extend along the International Boundary from 40 to 60 miles beyond the

Province of Manitoba. Attention is also being directed to the subject of

stockraising, for which that section of the Territories lying along the

easterly base and slopes of the Rocky Mountains is said to offer unusual

facilities, in the way both of shelter and pasturage, cattle being able

to subsist in the open air during the whole winter, and being found in

good condition in the spring. A number of people are already engaged in

the pursuit of this industry, and with so much success that there is

every probability of its further development by gentlemen of experience

in stock-farming and possessed of large capital, both from Great Britain

and the older Provinces."

The officers in charge

of posts at the end of the year 1879, were Superintendent W. 1). Jarvis,

Saskatchewan; Supt. J. Walker, Battleford; Supt. W. H. Herchmer, Shoal

Lake; Supt. J. M. Walsh, Wood Mountain; Supt. L. X. F. Crozier, Fort

Walsh; and Supt. Wm. Winder, Fort Macleod.

Surgeons Kittson and

Kennedy were in medical charge at Forts \\ alsh and Macleod

respectively.

The Commissioner

recommended that as soon as practicable in the spring, there be a

redistribution of the force as follows:—Fort Macleod, 2 divisions; Fort

Walsh, 2 divisions; Fort Qu'Appelle, 1 division; Fort Saskatchewan and

Battleford, 1 division, with such outposts as may be thought necessary.

The Commissioner considered it advisable on account of the large number

of Indians who would undoubtedly flock back in the spring to both the

Cypress Hills and the Bow River country, that the force mentioned should

be kept at these posts. It was felt that it would be some time before

these people could be settled down on their reserves, and there would be

a great deal of trouble making them do so.

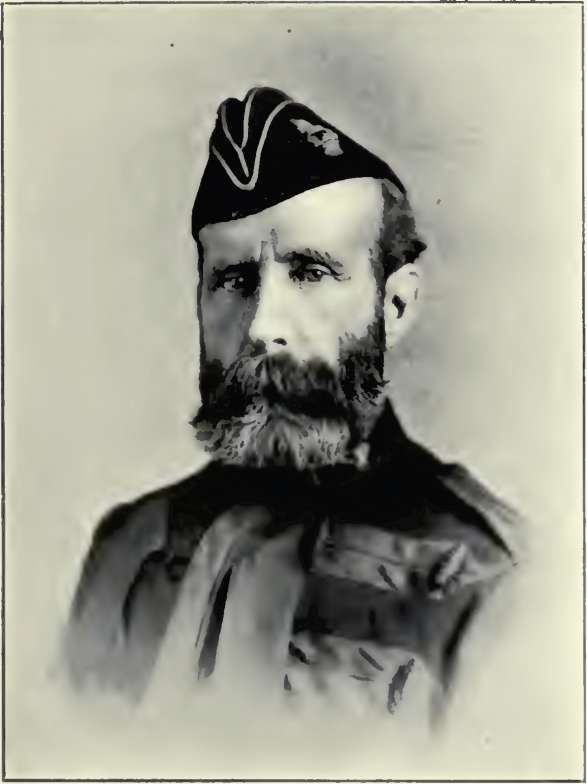

Lieut.-Colonel A. G. Irvine, Commissioner of the Norm-West Mounted

Police—

1880— 1886.

At all the Indian

payments in the North-West, in 1870, the officers and men of the Police

took over and attended to the distribution of the supplies and at all

places in Treaties No*. 0 and 7, with the exception of Sounding Lake,

Battleford and Port Pitt, they performed the duties of paymasters. In

accordance with instructions received from the Department, an escort

from Fort Walsh of two officers and 30 men proceeded to and attended the

payments at Qu'Appelle under Superintendent Crozier, and another from

the same post, consisting of one officer and fifteen men, under

Inspector Dickens, attended the payments at Sounding Lake, supplementing

another escort from Battleford under Inspector French; and another

escort, consisting of one officer and fifteen men, under the command of

Inspector Cotton, accompanied the Right Reverend Abbott Martin to Wood

Mountain on an unsuccessful mission to Sitting Bull and his Sioux on

behalf of the United States Government.

In addition to their

other multitudinous duties, the Mounted Police in 1879 undertook farming

operations of an experimental and extended character in Southern

Alberta. The Commissioner reported:—

"Farming operations on

the Police Farm about 30 miles from Fort Macleod have been carried on

with great success for a first year's trial. I am satisfied that next

year they will yield as good returns as Inspector Shurtliff expects. The

farm is beautifully situated, the soil is excellent, and it only

requires the earnest attention of those who have to do with it to make

it a success in every way."

Lieut.-Col. Macleod

during the year held several civil courts, both at Fort Walsh and

Macleod, claims for over eight thousand dollars having been entered and

adjudicated upon. In order to visit the different posts, and carry out

the duties he was instructed to perform, the Commissioner travelled in

waggons and on horseback over two thousand three hundred miles.

Owing to the complete

failure of the buffalo hunt in 1879 there was a famine among the

Southern Alberta Indians, and the police at Fort Macleod and other posts

were taxed to their utmost resources in affording relief. Messengers and

deputations from Crowfoot were constantly arriving, asking assistance

and reporting the dying condition, and even deaths, of many of the

Blackfeet and allied tribes from starvation. Superintendent Winder, in

command at Fort Macleod despatched Inspectors Mcllree and Frechette, at

different intervals to the camp ai the Blackfoot Crossing, with such

provisions as he was able to get, to the relief of the Indians, ami to

the extent he was able to spare from his limited quantity of stores; at

one tune the police stores at Macleod were reduced down to six bags of

flour on hand. At this time (.June) from 1.200 to 1 ,500 Indians

(Bloods, Peigans and Sureees), encamped around the Pent, were being fed,

and later on as many as 7,000 men, women and children, all in a

destitute condition, applied for relief. Beef and flour were distributed

every other day m small quantities to each family. The Superintendent,

himself always attended at this distribution, in order that *f any

Indian complained of not receiving his portion he could settle the

difficulty.

In this he was assisted

by the officers, non-commissioned officers and men. This continued until

after the payments were made, in October, when the majority of the

Indians left for the Milk River country, south of the boundary line, in

quest of buffalo.

At this time the

officers of the various posts found the actual duties so exacting that

they were unable to spare the time for the training of the men that they

would have liked. For instance in his report dated Fort Walsh, December

29, 1879, Superintendent Crozier wrote:

"I have the honor to

inform you that the force at this fort, considering the great amount of

detachment, escort and other duty during the summer, and continually

being done, is, as regards their drill and knowledge of general duties,

efficient. It will be understood that it is quite impossible to take raw

recruits and in a few months, while, at the same time, doing all the

various duties they may be called upon to do, bring them to a state of

perfection. The recruits have not had the instruction in equitation that

I should have wished, had their other duties not been so heavy. In my

opinion, it would tend greatly to the efficiency of the force if a depot

for the training and instruction of recruits was established where they

would remain for a stated time, solely for that purpose, before being

allowed to do general duty. Such an establishment would, I consider, now

that the term of service is five years, be much more feasible than when

three years was the term."

The distribution of the

force this year (1879) was as follows:—

"A" Division, Fort

Saskatchewan; "B" Division, Fort Walsh and Outposts; "C" Division, Fort

Macleod; "I)" Division, Shoal Lake and Outpost; "E" Division, Forts

Macleod and Calgary; "F" Division, Battleford.

Several, now important

outposts, were established this year and the preceding one. The Prince

Albert post was established as an outpost of Battleford early in the

winter of 1878, principally to look after the wandering bands of

Minnesota Treaty Sioux Indians, who were said to be causing annoyance to

the settlers by petty pilfering, etc., but after the arrival of the

police not a single case of pilfering was charged against them.

In February, 1879,

Supt. Walker, in command at Battleford, received intelligence that Chief

Beardv of Duck Lake and his band of Indians, had threatened several

times to break into Stobart, Eden Co's store and help themselves to the

Indian stores there. Complaints from the settlers of that neighbourhood

were also sent to Lieutenant-Governor Laird. After consulting with His

Honour, the police authorities decided that it would be expedient to

station a few policemen at Duck Lake for a time.

The barrack

accommodation was generally bad. For instance Superintendent Walker

reported as follows as to the Battleford barracks on December 19: —"The

Battleford barracks are just as you saw them last summer, except that

they were all mudded over when the cold weather set in. They are still

very uncomfortable; we are now burning from four to five cords of wood

per day, and it is only by keeping on fires night and day that the

buildings are made habitable. This morning, with the thermometer 37°

below-zero, water was frozen on the top of the stove in my bedroom,

notwithstanding there was sufficient fire in the stove to start the

morning fire."

Superintendent James Walker, now a leading- resident of Calgary.

Lieut.-Col. J. F.

Macleod, C.M.G., Commissioner of the force, having been re-appointed a

Stipendiary Magistrate for the North-West, on the 1st of November, 1880,

resumed the duties connected with that position, the district assigned

to him being the southern and south-western section of the Territories,

with residence at Fort Macleod. Lieut.-Col. A. G. Irvine, an officer of

ability and experience, who had, since 1877, been Assistant

Commissioner, was promoted to the com-command of the force.

Lieutenant-Colonel

Acheson Gosford Irvine was the youngest son of the late Lieut.-Col.

Irvine of Quebec, Principal A.D.C. to the Governor-General of Canada,

and grandson of the Honourable James Irvine, for many years a member of

the Executive and Legislative Councils of Lower Canada. He was an active

member of the Militia of the Province of Quebec, and obtained high

certificates of qualification at the old Military School held in

Montreal. He took part in Wolseley's expedition to the Red River in 1870

as Major of the 2nd (or Quebec) Battalion of Rifles, with such

distinction, that he was selected for the command of the permanent force

of a battalion of infantry and a battery of artillery selected for

service in Manitoba, retaining that command with universal acceptance

until the reduction of the force after the organization of the

North-West Mounted Police, and being transferred to that body as

Assistant Commissioner. While ,n command of the permanent force in

Manitoba. Lieut.-Colonel Irvine commanded the force of permanent troops

and Manitoba volunteers which proceeded to the United States frontier on

active service at the time of the Fenian incursion in 1871.

The most amicable

relations continue to exist between the police and the Indians, and

manifestations increased of growing confidence and good feeling on the

part of the latter. Although at this period partially relieved of the

responsibility of making treaty payments owing to the appointment of

officials in the direct service of the Indian Department, service in the

way of furnishing escorts to persons charged with the conveyance of the

treaty money, and in assisting the agents during its disbursement, was

frequent.

Shortly after his

appointment, the new Commissioner recommended that the pay of

non-commissioned officers and men be increased by length of service, in

cases where such service had been in all respects satisfactory. This, he

felt, would take the place of good conduct pay in the British service,

and would, he thought, prove a strong incentive towards inducing men to

conduct themselves properly during their term of service, which under

existing regulations was of considerable length, five years; more

particularly as free grants of land hail ceased to be any longer given

.n recognition of good service.

The distribution of the

force at the end of the year 1881 was as follows:—

"A" Division—Fort

Walsh—1 Superintendent, 1 Inspector, 3 Sergeants, 1 Corporal, 22

Constables.

"B" Division—Fort

Walsh—1 Superintendent, 13 Constables. Qu'Appelle—1 Superintendent, 1

Inspector, 3 Staff Sergeants, 4 Sergeants, 1 Corporal. 37 Constables

Shoal Lake—3 Constables. I Sergeant. Swan R ver—1 Inspector, 2

Constables.

"C" Division—Fort

Macleod—1 Superintendent. 2 Inspectors, 3 Sergeants, 2 Corporals. 25

Constables. Blackfoot Crossing—1 Inspector, 1 Sergeant, I Corporal, 12

Constables. Calgary—1 Sergeant, 1 Corporal. 6 Constables. Macleod

(Farm)—1 Inspector, 4 Constables. Blood Indian Reserve—1 Corporal, 1

Constable.

"D" Division—Battleford—1

Staff Officer, 1 Superintendent, 1 Inspector, 1 Staff Sergeant, 2

Sergeants, 5 Corporals, 32 Constables. Saskatchewan—1 Inspector, 2

Sergeants, 9 Constables. Prince Albert—1 Sergeant, 1 Constable. Fort

Walsh—1 Inspector, 2 Sergeants, 2 Corporals, 29 Constables.

"E" Division—Fort

Walsh—1 Inspector, 2 Sergeants. 2 Corporals, 29 Constables.

"F" Division—Fort

Walsh—2 Staff Oflicers. § Staff Sergeants, 1 Corporal, 12 Constables.

Wood Mountain—1 Inspector, 2 Staff Sergeants, 1 Sergeant, 1 Corporal, 15

Constables. Total 293.

In the reports of the

officers commanding posts for 1880. several important facts were noted.

Superintendent W. D. Jarvis at Fort Macleod, reported that until the end

of October he had not enough men to carry on the ordinary barrack

duties. Nevertheless, the fewr he had worked most creditably, and did

severe duty without complaint. He found the horses of "C" Division

nearly worked out, and, with the customary ration of oats, it was

impossible to get them into or keep them in condition. The stables w ere

destroy ed by fire on the 5th December. A few horses were after that

event billeted in the village, the remainder being herded on Willow

Creek, about three miles from the post, and were doing as well as could

be expected for horses in low condition. Superintendent Jarvis

particularly called attention to the soldier-like behaviour of a

detachment of thirty men under Inspector Denny, who were obliged to ride

to Fort Calgary and back, a distance of 200 miles, in the depth of

winter, without tents or any of the usual comforts of a soldier on the

line of inarch. The total amount of customs duty collected at Macleod by

the police for the year 1880 amounted to $15,433.38. There had been

fifteen cases tried by police officers, besides those brought before the

resident Stipendiary Magistrate. Sixty gallons of smuggled whiskey had

been seized and destroyed.

Superintendent W. IF

Herchmer, who had taken over the Battleford command had made some

changes in the disposition of his force.

At Prince Albert, lie

found that the quarters occupied by the men were totally unsuited to

requirements, several families occupying the same building, which was

horribly cold, and the stabling miserable. The Superintendent succeeded

in renting desirable premises, thoroughly convenient as to situation and

accommodation for men horses and stores, and easily heated, and moved

the detachment in. He also removed the detachment from Duck Lake to

Prince Albert for the reason that the quarters occupied were required by

the owners, and no other building was attainable; also because the

reason for which the detachment was sent there no longer existed, as the

Indians of that neighbourhood were showing a desire to be

peaceable,—this change being a result of the lesson taught them the

previous summer.

In the execution of

duty during the year, Superintendent Herchmer had travelled over 4,000

miles, and Inspector Antrobus, 2,000.

In 1881, the police had

considerable trouble, and only by the exercise of diplomacy, firmness

and great courage, avoided much more serious trouble, on account of

Canadian Indians stealing horses in the United States and bringing them

across the lines. Superintendent Crozier at Wood Mountain was informed

that a party of the Canadian Bloods had just returned to the reserve

from a successful horse raid in Montana.

Immediately he sent a

party to the Blood Reserve, recovered sixteen head of horses and two

colts, and arrested eight Indians who had been implicated in stealing

the property in Montana and bringing it into Canadian territory. On the

return of this party from the Blood Reserve, Crozier sent another one to

the mouth of the Little Bow River; that succeeded in capturing another

Indian and recovering two more head of horses.

Another horse was also

procured, making 19 in all, that had been feloniously stolen in the

United States. The Court, taking into consideration that no Indians had

heretofore been punished for this offence, and that what they had done

was not considered by them a crime, deferred sentence, and, after a

caution, allowed the prisoners their liberty.

Major Crozier pointed

out—"If the Legislature of Montana could be induced to pass a law

similar to the one we have, not only would the bringing to justice of

horse-thieves on both sides of the line be greatly facilitated, but the

existence of such a law in both countries would doubtless have the

effect of putting an end to horse-stealing to a very great extent. I

would suggest that immediate steps be taken by our Government to bring

to the notice of the proper authorities in Montana the existence of this

law in Canada, and the advisability of the Legislature of that territory

enacting a reciprocal measure."

In order to afford

further proof of the trouble taken by the police in the recovery of

property, stolen by Canadian Indians south of the line, it might be

mentioned that, in June the same year the officer commanding at Fort

Macleod reported that several Montana ranchmen arrived at that place in

search of horses, alleged to have been stolen in the United States by

Blood Indians. In order to recover, as far as possible, the stolen

property, an officer and party were sent to the Blood reservations. The

account of the duty performed is shown in the following extract of a

letter from Inspector Dickens, who commanded the party. From this it

will be observed, that a portion of the stolen property was recovered,

but not without trouble and personal risk.

"I have the honour to

report that in obedience to orders I proceeded on the first instant to

the Blood Reservation to search for horses stolen from American citizens

on the other side of the line. I was accompanied by Sergeant Spicer,

Constable Callaghan and the American citizens. On arriving at the

reservation, I had an interview with ' Red Crow,' the chief, and

explained to him that it would be better for his young men to give up

the horses, so as to avoid further trouble, and he said he would do his

best to have the horses returned; but he did not appear to have much

control over the Indians, who were very loth to give up the stolen

horses. Eventually, I recovered fourteen horses, which were identified

by the Americans, and placed them in a corral. While we were waiting

near the agency for another horse which an Indian had promised to bring

in, a minor chief, ' Many Spotted Horses' appeared and commenced a

violent speech, calling upon the Indians not to give up the horses, and

abused the party generally. I refused to talk with him and he eventually

retired. I went over to Rev. Mr. Trivett's house for a few minutes, and

on returning was told that an Indian who goes by the name of 'Joe Healy'

had said that one of the Americans had stolen all ' Bull Back Fats'

horses last winter and had set the camp on foot. This the American

denied, but the Indians became violent and began to use threatening

language. The American went up to the corral, and ' White Cap' who had

just come in, collected a body of Indians who commenced howling and

yelling and started off to seize the Americans. It was impossible at the

time to get a word in, so I started in front of the Indians towards the

corral, and shouted to the party to mount their horses and to be ready

to start in order to avoid disturbance. 1 mounted my horse and placed

myself in the road between the party and the Indians, who began to

hesitate. Sergeant Spicer, who was behind the crowd, called out that he

wished to speak to them for a few minutes, and seeing the party all

mounted, I rode back and met the Sergeant coming out of the crowd of

Indians, who became quieter but who were still very sulky. No more

horses being forthcoming, we collected the band and rode out of the

camp. I thought it best to get both men and horses as far away from the

reservation as possible that night; and after supping at Fred Watcher's

ranch, we started for Fort Macleod, and although 1 heard a report that a

war party, had gone down the Kootenay River to intercept our passage, we

forded the river safely and reached Fort Macleod without being molested.

"I took care when I

first went into the camp to explain to the Indians from whom I took

horses, that if they had am claim on the horses or any cause of

complaint, they could come into the fort and lay their case before you.

"I was well satisfied

with Sergeant Spicer, who showed both coolness and tact."

In January, 1SS2,

serious trouble occurred with the Blackfoot Indians on their reserve at

the Blackfoot Crossing. This was in connection with the arrest of a

prisoner, named "Bull Elk", a Blackfoot Indian, on the charge of

shooting with intent to kill; the Indians endeavouring to offer

resistance to the detachment first sent out to make the arrest. Prompt

steps were, however, taken by the officer commanding at Macleod,

Superintendent Crozier, who himself proceeded with every available man

at his command to reinforce the detachment at the Blackfoot Crossing.

"Bull Elk" was arrested and committed for trial, and every precaution

taken to meet any resistance that might have been offered by the

Indians. It was pointed out to them in the plainest possible manner that

law and order were to be carried out, that the police were in the

country to do this and that any attempt at resistance on their part

would be punished as it deserved. Seeing the determination on the part

of the police to carry out the letter of the law. and finding that a

determined force was at hand with which to enforce strict obedience and

respect, even should it be found necessary to resort to the most extreme

measures, the Indians submitted to the arrest of "Bull Elk", being

forcibly reminded in so doing that resistance on their part would not be

tolerated for a moment, or in any way allowed to interfere with the

impartial administration of justice, in the case of Indians and white

men alike.

At this time the

Commissioner deemed it advisable to reinforce the strength of Fort

Macleod by thirty non-commissioned officers and men lie therefore

ordered a detachment of that number to proceed from Fort Walsh to Fort

Macleod with all possible despatch.

In his report of the

original trouble, Inspector Dickens, in command of the detachment at the

Blackfoot Crossing, stated that, when on January 2nd. Charles Daly of

the Indian Department reported that "Bull Elk" had fired at him. he

(Inspector Dickens) went over and arrested the man.

and took him over to

the post. A crowd of Indians followed, all very excited. While the

Inspector was enquiring into the case, a large body of Indians gathered

from various quarters and gradually hemmed in the men who were placed

outside to keep them back, and others surrounded the stables, and were

posted along the roads. The police were at once cut off from water and

from the store-house, the number of Indians increasing as they began to

arrive from the camps. Dickens sent for Crowfoot. He arrived with the

other chiefs. He said that he knew "Bull Elk" was innocent, that some of

the white men had treated the Indians like dogs. He begged that "Bull

Elk" might not be sent into Macleod. After a long talk it was evident

that the Indians were determined to prevent the prisoner being taken

out. It was impossible to get a horse saddled to make a road through the

throng. Crowfoot said that he would hold himself responsible for the

appearance of the prisoner, if the Stipendiary Magistrate or some

magistrate came to try the case. As it was utterly impossible to get the

prisoner to Macleod owing to the roads being completely blockaded,

Dickens told Crowfoot that lie would let him take charge of the prisoner

if he promised to produce him when required. This he said he would do,

and the Inspector let him take the prisoner. The agent said he never saw

the Indians in such a state before.

Superintendent

Crozier's official report shows how critical the situation at this time

was. lie arrived at the Blackfoot Crossing on the evening of January the

6th, having travelled day and night.

On the following

morning he proceeded with the interpreter to that part of the camp in

which the prisoner "Bull Elk" was, and brought him from the camp to the

quarters occupied by the police, where the Superintendent, at once, as a

magistrate, commenced the preliminary examination of witnesses as to the

matter of the shooting by the prisoner. The Superintendent found

sufficient evidence to warrant him in committing the prisoner for trial,

and upon the evening of the second day, left the Blackfoot Crossing with

the prisoner and escort for Macleod. and arrived there on the evening of

the 16th. The Indians had been greatly excited. Upon Crozier's arrival

at the Blackfoot Crossing, Inspector Dickens reported to him that the

Indians were then quiet "but" said lie, "they are only waiting for an

attempt to be made to take the prisoner from them and they will

certainly resist." Crozier. therefore concluded to place the building in

a state of defence, as he had determined to arrest the offender, and,

having done so, to hold him, even if it were necessary to resort to

extreme measures. By eleven o'clock on the morning after his arrival,

the place was so defended that it would scarcely have been possible for

any number of Indians to take it, and, besides, the Superintendent had,

in the same buildings, protected the horses and the supplies of the

police and Indian Department, and had arranged to procure a supply of

water for both men and horses within the same building.

Before leaving Fort

Macleod he left orders for all available horses to be sent from the

farm, to have the guns in readiness, and upon the receipt of word to

that effect from him, to proceed forthwith to the Crossing. Dickens, it

should be stated, had diplomatically allowed the prisoner his liberty

temporarily, upon Crowfoot saying he would be responsible that he would

be forthcoming when required.

On the adjournment at

the conclusion of the first day of the preliminary examination, Crowfoot

again asked that the prisoner be allowed to accompany him to his lodge.

This request Crozier positively refused to accede to. After some

considerable time, seeing the police officer was determined not to give

in, Crowfoot and his people dispersed. Superintendent Crozier held the

prisoner in custody at the Crossing for one night and a day, and upon

the evening of the 8th, left with him under escort for Fort Macleod. The

prisoner was tried before the Stipendiary Magistrate and underwent

imprisonment for his offence in the guard room at Macleod. He was a

minor chief of the Blackfeet.

The immediate cause of

the difficulty seems to have been an altercation between the prisoner

and a white man employed on the reserve by the beef contractors.

The Indians were

evidently greatly impressed with the preparations Crozier had made.

Crowfoot asked him if he intended to fight, and the Superintendent

replied "Certainly not, unless you commence". He also explained to the

chief, as had often been done before, that the police had gone into the

country to maintain law and order, that if a man broke the law he must

be arrested and punished. Crozier asked him then if he, as a chief of

the Blackfoot nation, intended to assist him in doing his duty, or if he

intended to encourage the people to resist. The Superintendent further

said: "If I find sufficient evidence against the prisoner to warrant me

in so doing, I intend to take the prisoner to Fort Macleod, and when I

announce my intention of so doing I expect you to make a speech to your

people, saying I have done right."

Crowfoot did not

answer, beyond making excuses for the manner in which his people had

acted a few days before. However, at the conclusion of the examination

of witnesses, Crozier told them all that the prisoner was going to be

taken to Fort Macleod.

Crowfoot did then speak

to them in his usual vigorous manner, endorsing perfectly what the

police had done, and had decided upon doing. He and the other Indians by

this time saw that Crozier was determined to carry out any line of

action that he saw fit to commence.

The reinforcements that

had arrived from Fort Macleod in so short a time had astonished and awed

the Indians. For these reasons, the chiefs and people were willing to

listen to reason, and did so.

On the first of May,

1881, before the arrival of the recruits, Big Bear (then a non-treaty

chief) reached Fort Walsh. He came in ahead of his followers, all of

whom, numbering some 130 lodges, were, he informed Col. Irvine, en

route. The Commissioner at once told this chief, that he did not wish

his people to come in the vicinity of the fort, and also that he would

receive no aid from the Government. The Commissioner directed him to a

place known as the "Lake", where they could subsist by fishing.

This Big Bear did, and

for some time Col. Irvine heard nothing further from him. Later on,

however, he received information that councils were being held daily in

the Indian camp, and further that the result of these councils was that

Big Bear and his followers had decided to visit Fort Walsh, make

exorbitant demands for provisions, and in case of their being refused,

to help themselves. Colonel Irvine considered it advisable, thereupon,

to move all the Indian supplies inside the fort. These supplies had

previously been stored inside a building in the village rented by the

Indian Department. He also took over the ammunition of T. C. Power &

Bros., the only traders at Fort Walsh, and placed it in the police

magazine. The Commissioner confined all the men to barracks, had the 7

pounder mountain guns placed in position in the bastions, and made all

arrangements to have the force at his command ready for any emergency.

On the 14th, Big Bear with 150 bucks, all armed, arrived at the fort. By

runners going to his camp, Big Bear was kept informed of the action that

had been taken; the effect no doubt was salutary. Demands made for

ammunition during the council with Col. Irvine were refused, and there

is no doubt that Col. Irvine's treatment of Big Bear at this time had a

most satisfactory effect, showing him, that he as a non-treaty Indian

would not obtain assistance from the Government, and that any attempt of

his to obtain such by force must prove entirely futile.

On the 4th May, 1882,

Inspector Macdonell, the officer commanding at Wood Mountain, received a

report from Mr. Legarrie, trader, who had just returned from Fort

Buford, U.S., in which Inspector Macdonell was informed that on the

evening of the 28th April, while Legarrie was encamped en route to Wood

.Mountain, a war party of thirty-two Crees appeared and made demands for

provisions.

Mr. Legarrie had with

him a half-breed and a Sioux Indian. He and these men gave the war party

food. Shortly afterwards they took articles from the carts bv force, and

threatened the lives of his party. During the night Mr. Legarrie heard

the Indians in council arranging to kiJl him and the Teton Sioux.

Towards morning another council was held, when it was ascertained that

the Indians were composed of two parties, one from Cypress Hills, the

other from Wood Mountain. The Cypress Hills party wished that what had

been

Superintendent Macdonell.

arranged should be

carried into effect at once, lint the arrangements were changed, and it

was decided to allow Legarrie and his party, who had previously been

disarmed, to "eat once more" before killing them. When daylight came,

Legarrie commenced preparations for a start. The scene following he

describes as being a terrible one, the Indians having taken possession

of the carts. Legarrie expected every moment to be killed, the noise was

fearful, some crying for the scalps of the whole party, others only

wishing to k„!l the Teton Indian.

Two attempts at firing

were made, but fortunately the gun* missed fire in both cases. All

became so confused that the Indians were afraid of killing their own

friends. Finally Legarrie succeeded in buying off the lives of his men,

the war party being allowed to take what they liked and Legarrie's party

to go, after having had his carts pillaged, by the taking of blankets,

rifles, ammunition, etc.

Immediately on the

receipt of the information, Inspector Macdonell despatched messengers to

all the half-breeds and friendly Indians' camps within a radius of 20

miles of his post, instructing them to keep a watch for this war party,

and to immediately inform him if any trace was seen, promising that

unless the)' were captured, permanent quiet would not be established in

his district as the same party had given continual annoyance during the

spring. He therefore determined to make an arrest at any cost. Shortly

after, a half-breed, who resided 15 miles east of the post, reported to

Inspector Macdonell that on the previous evening he had. while herding

horses, come suddenly upon a war party of eight Indians on foot, all

having lariats (a sure sign that they were on a horse stealing

expedition). This war party admitted they were going to steal horses,

but promised to touch none belonging to the half-breed. From the

description gi\en of the Indians who had attacked Legarrie, the

half-breed assumed that they belonged to the same war party.

Inspector .Macdonell

immediately mounted every man of his command available, and in company

with Legarrie, whom he had sent for to identify the Indians, he started

to make the arrest. He travelled in the direction of a half-breed camp,

15 miles from the post in which direction the Indians had gone. On

arriving within a quarter of a mile of the camp, a scout was sent in to

gather information. The scout told the camp that he was in search of

four horses stolen from Wood Mountain, but he was told that they were

not there as eight Crees had just come in on foot. Inspector Macdonell

immediately pushed on to the camp, which was composed of about 45

lodges. On reaching the camp he found a large crowd collected, and all

the doors of the lodges closed, and on asking for the Cree Indians,

their presence in the camp was denied.

The crowded camp

appeared very sulky and averse to his searching the lodges, one

half-breed m particular who spoke a little English, showed much

opposition. Tins man Inspector Macdonell covered with his revolver. This

had the effect of cowing the crowd, and lodges were pointed out where

seven Crees were found. These were arrested and disarmed, and a demand

made for the remaining Indian, who was at last given up. The prisoners

were then conveyed to Wood Mountain Post. On the next day an examination

was held by Inspector Macdonell who committed them for trial, and

afterwards conveyed them to Qu'Appelle where they were tried and found

guilty by the Stipendiary Magistrate.

All possible aid has

been invariably given by the police towards the recovery and return to

their legitimate owners of horses and mules stolen and brought into

Canadian territory from the United States. The efforts in this respect

in 1882 were accompanied by marked success.

During the month of

May, of that year, a United States citizen from the Maria's River.

Montana, arrived at Fort Walsh. He gave a description of 11 horses which

he believed had been stolen from him by our Indians. A party of police

was sent out to the various

Superintendent A. H. Griesbach.

camps and succeeded in

recovering and handing over all the horses stolen, taking care that no

expense was incurred by the man who had suffered the loss.

At Qu'Appelle, 9 horses

and 6 mules, which had been stolen from Fort Buford, U.S.A., were

recovered by Inspector Griesbach-of "B" Division, and returned to

Messrs. Leighton, Jordon & Co., their owners, 1st Jan., 1883.

The United States

military authorities in all such cases aided the police as far as lay in

their power, which was more limited than that of the police.

General Sheridan, of

the United States Army, in his annual report for 1882, mentioned the

amicable relations which existed between the United States troops and

the Mounted Police Force, which, he said, "goes far in ensuring quiet

along the boundary line."

On the 29th of May,

1882, a party of some 200 Blood Indians arrived at Fort Walsh from their

reservation near Fort Macleod. These 200 men were well mounted and fully

equipped as a war party, all armed with Winchester repeating rifles and

a large supply of ammunition. On arrival they went at once to the

officer in command and reported that the Crees had stolen some forty

head of horses from them, and had been stealing all winter. The object

of their visit was to recover their stolen horses from the Crees, their

intention being to go on to the Cree cam]) at. "The Lake" east of Fort

Walsh. Feeling assured that, if this was done, serious trouble would

ensue, Supt. Crozier told the Bloods he would not allow this, promising

that he would send an officer and party, with a small number of their

representative men, to the Cree camp, and that if their horses wen1

there they would be returned to them. To this the Indians agreed.

Superintendent Crozier detailed Inspector Frechette for the duty; six

Blood Indians accompanied him to the Cree camp.

This officer returned

on the following day with three horses belonging to the Bloods. Crozier

was satisfied that, with the exception of two other horses, which were

afterwards returned by the Crees, the horses the Bloods had lost were

stolen by United States Indians.

This same year efforts

were made to induce several tribes to move from the dangerous vicinity

of the U. S. boundary to reserves selected for them in the north, where,

the buffalo having disappeared from the plains, the hunting was better.

Soon after Col.

Irvine's arrival at Fort Walsh in April, 1882, he commenced holding

daily councils with the Indians (Crees and Assiniboines) .with a view of

persuading them to move northward to settle upon the new reservations.

On the 23rd of June

"Pie-a-pot", with some five hundred followers, left Fort Walsh for

Qu'Appelle. A delay that arose from the time of " Pie-a-pot's" promise

to go on his new reservation until the time of his departure from Fort

Walsh, did not reflect discredit upon this chief, as regards any

inclination on his part to act otherwise than in perfect good faith, but

was purely owing to the lack of ability of the police to aid him in

transport. Such aid was imperative, as the Indians were wretchedly poor

and without horses. Considerable influence from different surreptitious

quarters was brought to bear with the view of inducing the Indians to

remain in the southern district, the object of course, being that they

should receive their annuities at Fort Walsh, and thus secure the

expenditure of the treaty money on that section of the country. Even

United States traders from Montana clandestinely visited the Indian

camps with the same project in view.

As far as practicable

Col. Irvine transported them with police horses and waggons. In

"Pie-a-pot's" case he sent four waggons, with a strong escort of police.

A portion of the escort, with one waggon, went through to Qu'Appelle;

the remainder of the •escort and waggons returned from "Old Wives'

Lake", where they were met by transport sent from Qu'Appelle by the

Indian Department.

At the time of

"Pie-a-pot's" departure from Fort Walsh, the Cree chief, "Big Bear"

(non-treaty Indian), "Lucky Man", 'and "Little Pine", with about 200

lodges, finding that Col. Irvine would not assist them in any way unless

they went north, started from Fort Walsh to the plains in a southerly

direction. These chiefs informed Col. Irvine that their intention was to

take "a turn" on the plains in quest of buffalo, and after their hunt to

go north. They added that they did not intend crossing the international

boundary hue,—a statement which he considered questionable at the time.

Colonel Irvine, therefore, at the request of the officer commanding the

United States troops at Fort Assiniboine, informed the United States

authorities of the departure of these chiefs. The Americans m expressing

their thanks were much gratified with the information imparted. If but

few did cross the line, they were deterred only by fear of punishment by

United States troops, who had formed a large summer camp at the big bend

of the Milk River.

At the time of the

departure of these chiefs from Fort Walsh. Col. Irvine told them that

the United States Government was opposed to their crossing the line, and

stated in a clear and positive manner that any punishment which might be

inflicted upon them by the United States troops could only be regarded

as the result of their own stubborn folly, in not acting upon the advice

of the Canadian Government, given purely in the interest of the Indians

themselves.

On December 8th, "Big

Bear" and his followers, who had not vet entered into a treaty,

accompanied by several treaty chiefs and Indians, went formally to

Colonel Irvine's quarters, and after having spent the afternoon and

evening in going over the details of previous interviews, he signed the

treaty \o. 0. which it will be recalled was made at Forts Carlton and

Pitt, which was the section of country to which Big Bear really

belonged. His announced intention at the time of signing was to go to

Fort Pitt with his entire followers in the spring and settle upon the

reservation allotted him.

Big Bear was the only

remaining chief in the North-West Territory who had not made a friendly

treaty with the Canadian Government, in the surrendering of his and his

people's rights as Indians, by the acceptance of annuities and reserves,

the occurrence consequently being considered an opportune one,

concluding as it did, the final treaty with the last of the many Indian

tribes in the Territories. Several /ears were to elapse, however, before

Big Bear's band redeemed the pledge and settled 011 the allotted

reserve.

By the departure of

these chiefs, Fort Walsh was entirely rid of Indians.

On account of the

increased responsibilities devolving upon the force, owing to the

construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway and the influx of settlers,

authority was given in the early part of the year 1882 for an increase

of the force by two hundred men.

In consequence of this

increase of the force, recruiting was commenced in Toronto, by the late

Superintendent McKenzie, at the New Fort. It was originally intended

that these recruits should be sent up via Winnipeg, then out to the

terminus of the Canadian Pacific Railway, and across country to the

various posts where they were required. However, owing to the severe

floods m Manitoba, which temporance suspended the railway traffic, as

well as the unsettled state of Indian affairs at Fort Walsh, the

original intention was changed and the recruits were taken up via Lake

Superior and the Northern Pacific Railway to Bismarck. Dakota, where

they embarked on the steamer "Red Cloud," and proceeded up the River

Missouri to Coal Banks, where they were met by Supeimtendent Mellree

with transport, and taken by him to Fort Walsh, distant about 120 miles.

They arrived on the 11th June. Superintendent McKenzie, who left Toronto

in command of the recruits, was shortly after taken ill and left at

Prince Arthur's Landing, where he died in a few days. The command was

taken over by Inspector Dowhng. In all, 187 recruits arrived, as well as

Surgeon Jukes and Inspector Prevost.

A small number of

recruits were also this year engaged at Winnipeg. 37 in all. These

recruits were taken on to Qu'Appelle and attached to "B" Division. Later

on, 12 more were taken up by1 Inspector Meele. In all 63 recruits

arrived at Qu'Appelle.

The total number of

recruits posted to the force in 1S82 was 2f)0, of whom 200 were the

increase of the force, and (he remainder to till vacancies, discharged

men, etc.

The recruits who

arrived at Fort Walsh were posted to "A " "C" and "H" Divisions. The

larger proportion of these recruits were excellent men, but some,

according to the Commissioner's report, were mere lads, physically unfit

to perform the services required. Colonel Irvine recommended most

strongly that the minimum age at which a recruit be accepted for service

be fixed at 21 years of age.

In speaking on this

same subject, Surgeon Jukes gave his experience in his annual report in

the following words: —"The examination papers given me when I was

examining recruits for admission to the force in May last, left me no

power to reject men otherwise eligible between the ages of IS and 40

years. This rule applies well to the regular army, where men enlist for

a longer period, where the duties ordinarily required are far less

severe; but for short periods of service, say 5 years, attended with

much exposure, and demanding considerable powers of endurance, the age

of IS is too young."

|