|

HEADQUARTERS REMOVED TO

REGINA

The Usefulness of Fort

Walsh Disappears, and the Post is Abandoned—Several New Posts

Established—Fort Macleod Moved—The Construction of the Canadian Pacific

Railway—A Record in Track-laying and an Equally Creditable Record in the

Maintenance of Order— Extra Duties Imposed Upon the North-West Mounted

Police.

EVER since the

establishment of the Mounted Police there had been uncertainty as to the

best place for the establishment of permanent headquarters. It has been

related how, in 1874, Swan River near Fort Ellice was chosen as the site

for headquarters and the erection of barrack and other accommodation

begun. It has also been explained that Lieut.-Colonel French, the first

Commissioner, on the return march from the Pelly River, arrived at Swan

River, but on account of the unpreparedness of the buildings, and the

lack of winter forage, due to prairie fires, left only one division at

and near Swan River, and proceeded with headquarters and the remainder

of his force to Winnipeg, and later to Dufferin, Man.

The next spring the

headquarters of the force were, under orders from the Government, and in

spite of Lieut.-Col. French's opinion that the site was unsuitable,

established at Swan River, but in a few years, owing to the vital

importance of preserving order among the numerous tribes of Indians in

the vicinity of the International frontier, and the necessity of putting

a stop to illicit trading across the lines, headquarters were first

removed to Fort Macleod, and in 1879, to Fort Walsh.

The Mounted Police

Buildings in the North-West Territories in 187G were as follows:—

Swan River,

accommodation for 150 men and horses

Hattleford, accommodation for 50 men and horses

Fort Macleod accommodation for 100men and horses

Fort Walsh accommodation for 100 men and horses

Fort Calvary accommodation for 25 men and horses

Fort Saskatchewan accommodation for 25 men and horses

Shoal Lake accommodation for 7 men and horses

The buildings at Swan

River and Battleford were erected by the Department of Public Works;

those at the other posts by the Mounted Police.

To the outside observer

it began to look as though the headquarters of the Mounted Police were

destined to be a perambulatory institution, but as a matter of fact,

within the force, and particularly on the part of those responsible for

Us efficiency, the idea of establishing a satisfactory permanent

headquarters for the force was never lost sight of.

Wood and Anderson's Ranch, On site of Old Fort Walsh.

In his annual report

for the year 1880, dated January 1st, 1881, the Commissioner, referred

to this subject as follows:

"1 am perfectly well

aware of the many important considerations that require to be most-

carefully weighed before a point for the headquarters of the force can

be finally settled upon. It is a matter that cannot be looked at merely

from a military point of view. The future construction of public works

throughout the North-West Territories, the rapid immigration that may

safely be anticipated, and the settlement that will necessarily

accompany it, must, I presume, also prove important factors as regards

the permanent establishment of police headquarters. It would then be a

most grievous mistake to arrive at and hastily formed conclusion which

might, and the chances are would, be a source of never ending regret.

"I propose that in

future the headquarters of the force be a depot of instruction, to which

place all officers and men joining the force will be sent, where they

will remain until thoroughly drilled and instructed in the various

police duties. To carry out this plan successfully, it is indispensable

that a competent staff of instructors be at my disposal. A portion of

such a staff I can obtain by selection from officers and

non-commissioned officers now serving in the force. In addition to this,

however, I recommend that the services of three perfectly well qualified

non-commissioned officers and men be obtained from an Imperial Cavalry

Regiment. I am satisfied that the inducements we could hold out would be

the means of obtaining the best class of noncommissioned officers to be

had in England. I would not recommend that non-commissioned officers of

more than five years service be applied for. Old men, who have already

spent the best days of their life in the British service, would be quite

unfit for the work that in this country they would be called upon to

perform, nor would they be likely to show that energy and pride in their

corps which is desirable that, by example, they should inculcate into

others. Instructors of the class I have described, in addition to the

knowledge they would impart to others, would serve as models for

recruits, as regards soldierlike conduct and general bearing. The

importance of the benefits the "force would thus derive cannot, in my

opinion, be overrated."

In the same report the

following reference was made to the unsatisfactory condition of the

barracks at headquarters and elsewhere:—"Complaints continue to be made

regarding the condition of the police buildings, and the character of

the accommodation they afford in their present state of repair. It is

most desirable that the barracks should be as comfortable as possible,

but it is not deemed expedient to incur any considerable expenditure

upon them at present, not until the line of the Pacific Railway has been

finally determined, as upon that determination will depend the situation

of the permanent headquarters; and it may then be found convenient to

abandon a number of the existing posts and construct others elsewhere.

There were obvious disadvantages attaching to the custom of permitting

detachments to remain throughout the entire length of service at one

post, and during spring the system was inaugurated of moving them to new

stations at least once in two years. It is, of course, understood that

the headquarters staff do not come under the operation of this rule."

During 1881, the

contract for the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway was made by

the Dominion Government with the Montreal syndicate at the head of which

were Messrs. George Stephen and Donald A. Smith (now Lord Mount Stephen

and Lord Strathcona). The work of pushing the gigantic work to

completion was at once taken up energetically, and with the laying of

the rails across the prairies a new era dawned for the North-West and

the Mounted Police. It was realized that the exact location of the line

woidd have much to do with the future distribution of the force and the

location of the permanent headquarters. In his report at the end of the

year 1881, the Commissioner wrote:

"The distribution of

the force cannot well be satisfactorily laid down until the exact

location of the Canada Pacific Railway is known. In any case there is an

immediate necessity for having a strong force in the Macleod district,

which includes Fort Calgary. In the meantime the following will give a

fairly approximate idea as to what I consider a judicious distribution,

viz:— Qu'Appelle, 50 noncommissioned officers and men; Battleford, 50

noncommissioned officers and men; Edmonton, 25 noncommissioned officers

and men; Blackfoot Country, 200 non-commissioned officers and men;

Headquarters, 175 non-commissioned officers and men. Total 500. It will

be observed that this distribution is based upon the assumption that my

recommendation, as regards the increase of the force, will be acted on.

I make no mention of Wood Mountain; for this section of the country I

propose utilizing the fifty men shown as being stationed at Qu'Appelle.

I understand the Canada Pacific Railway will run south of our present

post known as 'Qu'Appelle.' The chances are therefore, I will hereafter

have to recommend that the location of this post be moved south. Were

this done we would then have control of the section of country in which

Wood Mountain post now stands. The location of the present post at

Battleford may not require to be changed for some time at all events.

Edmonton would be an outpost from Calgary. Our present post in the

Edmonton district is Fort Saskatchewan, which is situated some eighteen

miles east of Edmonton proper. It is, I think, actually necessary that

our post be moved to Edmonton.

"There is, to my mind,

no possible doubt but that the present headquarters, Fort Walsh, is

altogether unsuitable, and I would respectfully urge upon the Government

the necessity of abandoning this post with as little delay as possible.

In making this recommendation I am in a great measure prompted by the

knowledge of the fact that the Indian Department do not consider that

the farming operations at Maple Creek have been successful in the past,

and that they are still less likely to prove so in the future."

At the time this report

was penned, Col. Irvine believed that the main line of the C.P.R. would

pass considerably north of the Cypress Hills and of its actual location

; as was first proposed, in fact. During 1882, the Commissioner was

notified by Mr. C. E. Perry, the engineer in charge of the work, that

the southern route had been adopted, and that considerable supplies

would have to pass through, or in the immediate vicinity of the Cypress

Hills. In view of the change, the Commissioner received a letter from

Mr. Perry, on the subject of the syndicate parties receiving protection

from the police. He was at the same time informed that large quantities

of supplies were to be shipped through Fort Walsh, and a considerable

number of men were to be employed at once in and about Cypress Hills.

This being the case, the situation of affairs was essentially changed,

and Col. Irvine was compelled to somewhat modify his previous

recommendations, in so far as they related to the immediate abandonment

of Fort Walsh, as he saw that it was actually necessary to maintain a

force of police m that vicinity for the protection of the working

parties from United States Indians as well as Canadian ones, and also to

prevent smuggling and illicit whisky dealing being carried on from the

United States territory. He therefore recommended that Fort Walsh be not

abandoned until the authorities were positively informed as to the

location of the Canadian Pacific Railway line, by which time a suitable

site for a new post could be selected, possibly, he thought, near the

crossing of the South Saskatchewan River, about 3o miles north-west of

the head of the Cypress Hills. On ascertaining the final location of the

Canadian Pacific Railway line, the Commissioner communicated with the

Minister of the Interior recommending that the site for future

headquarters be decided upon at once, and a suitable post be erected

without delay. He based this recommendation upon the assumption that the

site would be selected at or near the crossing of the South Saskatchewan

River. He stated, however, that should the Government consider that

point too far west for headquarters, it would nevertheless be necessary

to erect a post in the vicinity of the Cypress Hills.

By a telegram of the

20th July, 1S82, Col. Irvine was informed of Sir John A. Macdonald's

decision of the Pile of Bones Creek (now Regina) being the headquarters

of the force, also of the number and dimensions of the section buildings

to be made in the Eastern Provinces and forwarded to Regina, for stables

and quarters. This telegram reached Colonel Irvine at Fort Macleod.

Soon after his return

from that post to Fort Walsh, he proceeded to Qu'Appelle; and after

having inspected "B" division, accompanied His Honour the Lieutenant

Governor, the Hon. Edgar Dewdney, to the Pile of Bones Creek. The

Commissioner, after looking over the ground, instructed Inspector

Steele, who had accompanied him, where the buildings were to be

situated, and immediately moved the headquarters of "B" division from

Qu'Appelle to Regina. At the end of October the sectional buildings

commenced to arrive, and building was proceeded with.

The headquarters of the

force was transferred from Fort Walsh to Regina 011 the 6th of December.

A recruiting depot,

with an establishment of one officer and ten men was, under authority of

the Minister established in Winnipeg in the spring of 1882.

Building was carried on

extensively during the year 1883, not only at the new headquarters but

at other posts. During the year in question the buildings at Pile of

Bones Creek (or Regina) were completed. New barracks at Fort Macleod to

replace those previously in use, were in course of erection New posts

were pushed forward towards completion at Medicine Hat and Maple Creek.

There had been very

special and particular reasons for building a new post at Fort Macleod.

in fact a new site had to be selected. January 18, 1881. the

Commissioner reported that the course of the "Old Man's" River at Fort

Macleod had changed, This river, at high water, at this date, deviated

from its original course in two places, the stream, after this

unexpected freak of nature, passing nunediately in front and rear of the

fort, the post thus being made an island in rear the water flowed within

a few feet of the west side of the fort The deviations made from the

original course of the river continued, becoming more and more

formidable, and it was probable that in the coming spring many of the

post buildings would be carried away if left in their actual positions.

Taking all these things

into consideration it was felt to be absolutely necessary that Fort

Macleod be removed from its original site. The Commissioner recommended

that a new site be selected at the police farm, which was situated some

30 miles south-west from where the fort originally stood.

It appears that the Old

Man's River changed its course by breaking through a narrow neck of land

that divided the main stream from a slough. In 1880, the river reverted

to its old bed, breaking through lower down, cutting off another large

portion of the island on which the fort was built, and causing the

demolition of several houses. The soil of the island was a loose mixture

of sand and gravel, and to show the strength and velocity of the

current, it might be mentioned that in one night one hundred and twenty

yards of the bank was washed away. To save the saw-mill from being swept

away it was necessary to move it from its old site. The whole lower

portion of the island, including a part of the farm, was inundated, and

the water rose so high as to approach within twenty yards of the fort

itself. The level of the flood was not five feet from the floors in the

fort.

Nothing was done about

the selection of a new site until March, 1883,when the Commissioner was

informed that the latest site which had been selected for the erection

of the new post at Fort Macleod had been approved, and that the erection

of a new post was to be commenced during the following summer. The site

chosen was about two and a half miles west of the old post, on the bench

land overlooking the "Old Man's" River, and on the south side of it.

Every care was taken in the selection of the site. The soil was dry and

gravelly, good drainage was obtainable, plenty of fresh water was near

at hand, there was good grazing ground in the immediate vicinity, and an

uninterrupted view was afforded.

Work on the post was at

once begun and pushed to completion. The principal buildings were laid

out in a rectangle, 484 ft. long by 254 ft. wide, with officers'

quarters on west side, barrack rooms facing them on the opposite side,

offices, guard room, recreation room, sergeants' mess and quarters, on

the north side, with stables, store rooms, harness room, opposite; the

remaining buildings were outside the "square".

The buildings were of

the same general construction. All buildings rested on foundation blocks

about 12 inches square, and placed at intervals of 6 feet. These blocks

had a firm bearing on the hard, gravelly soil, a thin layer of soil and

mould being removed. All sills were 8 in. square, floor beams, 2 in. by

8 in., and were 2 ft. apart; framing 2 in. by 6 m. and were 18 m. apart,

with 0 in. square corner posts. Plates of two 2 in. by 6 in. scantling,

firmly spiked joists, which were 2 in. by 8 in. by 6 in. strongly braced

and firmly attached to ceiling joists, which were 2 in. by 8 in.

Every precaution was

taken to strongly brace the framing and roofs, to prevent any damage

resulting from the high winds which prevail at Fort Macleod.

All outside walls were

of common 1 in. boarding covered with tar paper, and then sided up with

5-8 in. siding, 6 in. wide and lap of 7-8 in.

The floors throughout

were of two thicknesses, with tarred paper between. Roofs were shingled,

with felt paper between shingles and sheeting. The window casings and

door frames were of neat appearance. The officers' quarters, barrack

rooms, mess room, hospital, offices and recreation room, were all lathed

and plastered in the interior; the guard room and store houses were

lined with dressed lumber. All doors leading to the exterior were 3 ft.

by 7 ft. and 1J in. thick inside doors, 2 ft. 6 in. by 6 ft. 8 in and 1

in. thick; with the exception of the barrack rooms all the doors were 3

ft. 7 in. The windows in all the buildings had twelve lights, 12 in. by

16 in. except in the kitchens of the officers' quarters and store and

harness rooms, which were each of twelve lights, 10 in. by 12 in.

All buildings were

painted a light grey, and trimmed with a darker shade of the same colour.

The wood work and casings in the interior were painted the same colour.

Roofs were painted with fireproof paint.

Chimneys were of zinc,

14 in. square with a circular flue, 7 in. in diameter, thus giving a

large air space, which was utilized as a ventilator. They projected 4

in. above the peak of the roof, and passed through the ceiling.

Owing to the distance

from the railway, 138 miles, it was impossible to construct the chimneys

of brick. Where stovepipes were carried through partitions, they were

surrounded by three inches of concrete.

This new post was

considered a masterpiece at the time it was built.

On the 10th of May

last, 1884, the new barracks were taken over from the North-West Coal

and Navigation Company, and occupied shortly after by "C" division, a

small party only being left as caretakers in the old buildings.

Fort Calgary having

been created a district post, and "E" division removed there, under the

command of Superintendent Mcllree, the buildings were entirely

inadequate to accommodate the Division, and were so entirely useless and

out of repair that Col. Irvine gave instructions to that officer to

commence building at once on his arrival, and to retain for use during

the winter such buildings as, with little, or no expense, could be made

habitable for the winter The buildings to be erected were to be laid out

in a general plan for a new post.

Calvary Barracks, erected in i888-89.

Superintendent Mcllree

immediately on his arrival commenced work Several of the old buildings

were pulled down to make way for the new ones, all the same logs being

utilized. A contract was at once let for the erection of a new barrack

room, 110 ft. long by 30 ft. wide, with (lining room, 30 ft. square, and

kitchen, 15 ft. square; attached, 1 guard room, 30 ft. by 50 ft., with

12 cells; 1 hospital, and 1 officers' quarters. These buildings were all

completed during 1882. The walls of the buildings throughout were 9 ft.

high and constructed of logs, with the exception of the officers'

quarters, which were frame. The cracks were filled with mortar. The

floors consisted of 7 inch planed lumber, tongued and grooved, while the

roof was of shingle laid in mortar. The buildings erected were good and

substantial ones, neat in appearance, well ventilated, and slited for

the requirements to which they were to be put. Much more commodious

barracks were erected at Calgary in 1888 and 1889.

For some considerable

time it had been the intention to abandon the old Fort Walsh post, which

had figured so prominently in the early history of the force, and

abandonment was desirable for many reasons. In the first place, the site

was, from a military point of view, a most objectionable one. The rude

buildings, always considered but a temporary refuge, had become utterly

dilapidated. The post, too, being some 30 miles south from the located

line of the Canadian Pacific Railroad, rendered a change of site

imperative, in addition to the fact of its being a temptation to

straggling bands of lazy Indians whose desire was to loiter about the

post, and when in a destitute condition, make demands for assistance

from the Government.

The Commissioner,

therefore, acting under usual authority, had the post demolished; the

work being performed by the police, commencing on the 23rd of May, and

concluding on the 11th of June. The serviceable portion of the lumber of

which the old buildings were composed, was freighted to the camp

established at Maple Creek, a point on the main line of the Canadian

Pacific Railroad, where the division previously stationed at Fort Walsh

was encamped during the summer.

Acting under the

direction of his Honour the Lieut.-Governor, a detachment, consisting of

one officer (Inspector Dickens) and twenty-five men, was, during the

month of September, 1883, stationed at Fort Pitt, and a police post

established there. This was done on account of reports which had reached

His Honour, to the effect that the Indians on reserves in that vicinity

were likely to give serious trouble.

At the end of 1882, the

Commissioner was able to report that the increase of the force, referred

to in an earlier chapter, had proved most judicious. The effect on the

Indians throughout the Territory had been to show them that the

Government intended that law and order should be kept, by both white men

and Indians alike, and that sufficient force was provided to accomplish

this. The cases of " Rig Bear" and of the trouble at the Blackfoot

Crossing, early in the preceding January, were sufficient to show that a

strong force was still necessary to enforce the law among the Indians.

The Commissioner was, owing to the increase of force, enabled to move a

sufficient force to Forts Macleod and Calgary, winch was urgently

required. At Fort Macleod there were the Blood and Piegan reservations,

numbering about four thousand people. The Sarcee reservation of about

five hundred was only ten miles from Calgary, and the Blackfoot reserve,

50 miles down the Bow River from that post. The fast growing settlements

about these posts, together with the large cattle ranches, rendered it

imperative that they should receive good police protection from such a

large body of Indians, in all about 7,000, as well as that order should

be kept among the Indians themselves.

Great vigilance was

required to prevent smuggling from Montana, U.S.

The following is a

return showing the amount of Customs duties collected by the North-West

Mounted Police, during the year 1882:—Port of Fort Walsh, up to 8th

December, $15,135.40; Port of Fort Macleod, up to 30th December.

S35.525.70; Port of Wood Mountain up to 31st December, $2,784.04; Port

of Qu'Appelle up to 31st December, $1,070.50—Total S52,522.30.

It can be readily

understood how largely the police work of the force was added to during

the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway. As the work neared the

eastern boundary of the Territories, the troubles then feared ma)- be

classified as follows:—

1st. Annoyance and

possible attack on working parties by Indians.

2nd. Difficulty of

maintaining law and order among he thousands of rough navvies employed;

and the prevention of whisky being traded in their midst md at all

points of importance along the line.

Fortunately, the

Indians were so kept in subjection hat no opposition of any moment was

encountered from them.

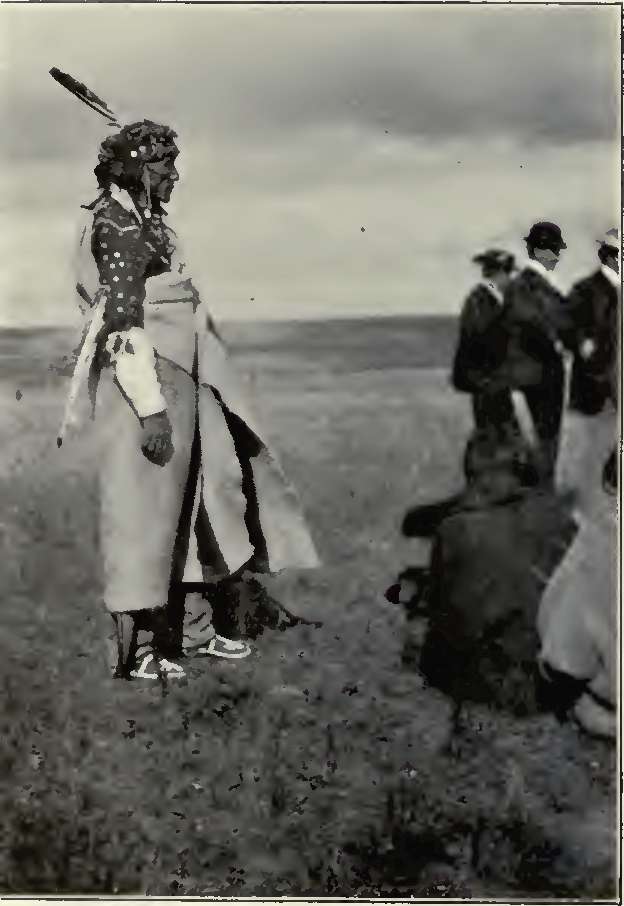

His Old Order and the New—An Indian at a Celebration of Whites near a

North-West Town.

As originally expected,

numerous and continued efforts were made to smuggle in whisky, at almost

I) points along the construction line. This taxed ie resources and

vigilance of the force to the utmost; but these labours were successful.

In the construction of

the railway during 1882, upwards of 4,000 men were employed during the

whole summer, some of them exceptionally bad characters, •wing, however,

to there being no liquor obtainable, very little trouble was given the

police, the contractors, the settlers, or anybody else, by them. Where

large amounts of money are being expended among such men as railway

navvies it is to be expected that many attempts will be made to ftp ply

them with liquor, and such attempts were made in the west in 1882. Had

this not been effectually stopped, the historian of the period would

have had to report a large number of depredations as having been

committed. It is probably unparalleled in the history of railway

building in an unsettled, unorganized western country that not a single

serious crime had been committed along the line of work during the first

year of operations, and this fact certainly reflected great credit on

those responsible for the enactment and carrying out of the laws.

The following is a copy

of a letter the Commissioner received from W. C. VanHorne, Esq., General

Manager of the Canadian Pacific Railway, just as he was preparing his

annual report:—

"Canadian Pacific

Railway,

Office of the General Manager,

Winnipeg, 1st Jany., 1883.

"Dear Sir.—Our work of

construction for the year of 1882 has just closed, and I cannot permit

the occasion to pass without acknowledging the obligations of the

Company to the North-West Mounted Police, whose zeal and industry in

preventing traffic in liquor, and preserving order along the line under

construction have contributed so much to the successful prosecution of

the work. Indeed, without the assistance of the officers and men of the

splendid force under your command, it would have been impossible to have

accomplished as much as we did. On no great work within my knowledge,

where so many men have been employed, has such perfect order prevailed.

"On behalf of the

Company, and of all their officers, I wish to return thanks, and to

acknowledge particularly our obligations to yourself and Major Walsh.

(Signed) W. C.

VaxIIorne. Lieut.-Col. A. G. Irvine,

Commissioner of

North-West Mounted Police, Regina."

The next year, 1S83,

the work of railroad construction was accompanied by increased duties

and troubles for the Mounted Police.

Track-laying on the

Canadian Pacific Railroad ceased in the month of January, at a point

some twelve or thirteen miles eastward of the station now known as Maple

Creek. Several parties of workmen employed by the railway company

wintered in the

Cypress Hills, cutting

anil getting out timber. These men, ignorant of Indian habits, were on

different occasions needlessly alarmed by rumours that reached them of

the hostile intentions of the Indians in the vicinity. On one occasion,

a timid attempt was made by a few Indians to stop their work, such

attempt at intimidation being prompted on the part of the Indians by a

desire to procure presents of food from the contractors. On

representation being made to the officer commanding at Fort Walsh,

prompt and effectual steps were taken to secure quietude, and prevent

any similar occurrence. On this subject Superintendent Shurfliffe

reported to Col. Irvine as follows:

"On the 7th inst., Mr.

LaFrance, a railway contractor, who was cutting ties in the

neighbourhood of Maple Creek, came to me and complained that a body of

Indians, under 'Front Man,' had visited his camp and forbidden them to

cut any more timber, saying that it was the property of the Indians, and

that they had also demanded provisions from them. Mr. La France and his

men being thoroughly frightened, at once left the bush and repaired to

the police outpost at Maple Creek and claimed protection. On hearing Mr,

LaFranec's complaint, I sent for 'Front Man.' and explained that it was

a very serious matter to interfere with any men working in connection

with the railway, and convinced him that it would not be well for him or

any other Indian to do anything having a tendency to obstruct the

progress of the road. On being assured that he would have 110 further

trouble, Mr. LaFrance resumed work."

The Pie-a-pot incident

, is one of the traditions of the force, for have not gifted pens

embalmed it.

The work of

construction was being rushed across the prairies west of Swift Current,

and right in the line of the engineers, directly where the construction

camps would soon be located with their thousands of passionate,

unprincipled navvies—the flotsam and jetsam of humanity—Pie-a-pot and

his numerous tribe had pitched their tents, and brusquely announced that

they intended to remain there.

Now Pie-a-pot and his

band had not just then that wholesome respect for the law of "The Big

White Woman" and the red-coated guardians thereof which a few months

additional acquaintance were to confer. Moreover it is as true with the

aborigines as with other people that "Evil communications corrupt good

manners." and in spite of the efforts of the police, Pie-a-pot's band,

or individual members thereof, had been just enough ii) communication

with the railway construct ion camps to be decidedly corrupted. The

craze for the whiteman's money and whisky raged within the numerous

tepees of Pie-a-pot's camp. In fact, just then Pie-a-pot's band fairly

deserved the appellation of "Bad Indians," and even the possibility of

the massacre of some of the advanced parties engaged in the railway work

was darkly suggested As the army of navvies advanced towards the Indian

camp, and the latter remained sullen and defiant, the railway officials

appealed to t he Lieutenant-Governor for protection. His Honour promptly

turned the appeal over to the Mounted Police, and, with just as much

promptitude, means w ere taken to remove the difficulty. Pie-a-pot had

hundreds of well-armed braves spoiling for a fight, with him, but it is

not the custom in the North-West Mounted Police to count numbers when

law and duty are on their side. Soon after the order from headquarters

ticked over the wires, two smart, red-coated members of the force, their

pill-box forage caps hanging jauntily on the traditional three hairs,

rode smartly into Pie-a-pot's camp, and did not draw rein until in front

of the chief's tent.

Two men entrusted with

the task of bringing a camp of several hundred savages to reason! It

appeared like tempting Providence—the very height of rashness.

Even the stolid Indians

appeared impressed with the absurdity of the thing, and gathering near

the representatives of the Dominion's authority, began jeering at them.

One of the two wore on his arm the triple chevron of a sergeant, and

without any preliminary parley he produced a written order and proceeded

to read and explain it to Pie-a-pot and those about him. The Indians

were without delay to break camp and take the trail for the north, well

out of the sphere of railway operations. Pie-a-pot simply demurred and

turned away.

The young bucks laughed

outright at first, and soon ventured upon threats. But it did not

disconcert the two redcoats. They knew their duty, and that the written

order in the sergeant's possession represented an authority which could

not be defied by all the Indians in the North-West. The sergeant quietly

gave Pie-a-pot warning that he would give him exactly a quarter of an

hour to comply with the order to move camp, and to show the Indian that

he meant, to be quite exact with his count, he took out his watch.

Again Pie-a-pot

sullenly expressed his intention to defy t he order, and again the young

braves jeered. They entered their tepees, and when they returned they

had rifles in their hands. The reports of discharged lire-arms sounded

through the camp, a species of Indian bravado. Some turbulent characters

of the tribe mounted 'heir ponies and tried to jostle the mounts of the

two redcoats as they calmly held their positions in front of Pie-a-pot's

tepee, some young bucks firing off their rifles right under the noses of

the police horses. Men, women and even children, gathered about jeering

and threatening the representatives of law and order.

They knew that the two

men could not retaliate. Pie-a-pot even indulged in some coarse abuse at

the expense of his unwelcome visitors, but they sat their horses with

apparent indifference, the sergeant taking an occasional glance at his

watch.

When the fifteen

minutes was up he coolly dismounted, and throwing the reins to the

constable, walked over to Pie-a-pot's tepee. The coverings of these

Indian tents are spread over a number of poles tied together near the

top, and these poles are so arranged that the removal of a particular

one. called the " key-pole." brings the whole structure down. The

sergeant did not say anything, but with impressive deliberation kicked

out the foot of the key-pole of Pie-a-pot's tepee, bringing the grimy

structure down without further ceremony. A howl of rage at once rose

from the camp, and even the older and quieter Indians made a general

rush for their arms.

The least sign of

weakness or even anxiety on the part of the two policemen, or a motion

by Pie-a-pot. would have resulted in the speedy death of both men, but

the latter were, apparently, as calm as ever, and Pie-a-pot was doing

some deep thinking.

The sergeant had his

plan of operations mapped out, and with characteristic sang-froid

proceeded to execute it. From the collapsed canvas of Pie-a-pot's tepee

he proceeded to the nearest tent, kicked out the key-pole as before, and

proceeded to methodically kick out the key-poles all through the camp.

As W. A. Fraser, the

brilliant Canadian novelist, writing of this remarkable incident, put

it, Pie-a-pot had either got to kill the sergeant—stick his knife into

the heart of the whole British nation by the murder of this unruffled

soldier—or give in and move away. He chose the latter course, for

Pie-a-pot had brains."

During the month of

December, 1883, a very serious strike occurred on the Canadian Pacific

Railway line, the engineers and firemen refusing to sign such articles

of agreement as were proposed and submitted to them by the railway

authorities; these workmen making demands for increased rate of pay,

which, being refused by the Company, led to the cessation of work by

engineers and firemen all along the line. It at once became apparent

that the feeling between the Company and their employees was a bitter

one. This being the case, and the Company further finding that in

addition to its being deprived of skilled mechanical labour, and also

that secret and criminal attempts were being made to destroy most

valuable property, the services of the N.W.M.P. were called into demand.

A detachment of police,

consisting of two officers and thirty-five men, was placed under orders

to proceed to Moose Jaw. On the evening of the 10th December, Mr. Murray

of the C.P.lt. reached Regma with an engine and car, and the detachment

proceeded forthwith to Moose Jaw, which was the end of a division, and

40 miles west of headquarters. On arrival at Moose Jaw, Superintendent

Herchmer, commanding the detachment, placed a guard on the railway round

house at that place. From the assistance rendered by the police the

railway company was enabled to make up a train, which left for the east

on the following morning with passengers and mails. By this train Supt.

Herchmer, with nineteen men, proceeded to Broadview, the eastern end of

the same rail way division.

Colonel S. B. Steele, C. B., etc., formerly Inspector and later

Superintendent in the North-West Mounted Police.

During the year 1884,

the progress of the Canadian Pacific Railway construction, then

approaching the mountain section from across the prairie, was made as

uninterruptedly as heretofore. The large influx of miners and others

into the vicinity of the mines in the mountains on the resumption of the

train service in the spring (the service wras suspended during the

winter), necessitated a material increase in the strength of the Calgary

division, the headquarters strength of which it was advisable to

diminish as little as possible.

In March, Inspector

Steele, who was commanding at Calgary, in the absence of Superintendent

Mcllree, on leave, reported that preparations were on foot for the

illicit distillation of liquor in the mountains, and in June called

attention to the difficulty of checking illegal importations into

British Columbia under the narrow latitude imposed by the Peace

Preservation Act applying to the vicinity of public works. This latitude

was subsequently extended to twenty miles on each side of the railway

track. On the 10th of May, in consequence of a message from the manager

of construction, anticipating trouble at Holt City and its neighbourhood,

Sergt. Fury and ten men were posted there for duty, two being retained

at the 27th siding, and a corporal and four men at Silver City, and

these men, for the time, maintained order amidst the rowdy element in a

highly creditable manner. On the 5th June, Superintendent Herchmer

assumed command of the Calgary district, being accompanied from

headquarters by a reinforcement for "E" division, of two non-connnissioned

officers and 22 men. On the 21st June, a detachment of mounted men was

dispatched to the Columbia River, to protect the railway company's

property and interests at that point.

A detachment of the

force under Inspector Steele, was employed in the maintenance of law and

order on that part of the Canadian Pacific Railway under construction in

the mountains, during the early part of 1885. The distribution of this

detachment was as follows:—Laggan, 3 men; 3rd Siding, 2 men; Golden

City, 8 men, 7 horses; 1st Crossing, 4 men, 2 horses; Beaver Creek, 2

men, 1 horse; Summit of Sell.irks, 2 men, 1 horse: 2nd Crossing, 4 men,

2 horses. A little later, as construction proceeded, Golden City was

left with three men and one horse, the balance being moved on to Beaver

Creek. In the absence of gaol accommodation for the district of Kootenav,

cells were constructed at the 3rd Siding, Golden City, 1st Crossing,

Beaver Creek, Summit or Selkirks and 2nd Crossing. A mounted escort of

four constables was detailed to escort the Canadian Pacific Railway

paymaster whenever he required it.

Inspector Steele

reported:

"About the first day of

April, owing to their wages being in arrears, 1,200 of the workmen

employed on the line struck where the end of the track then was, and

informed the manager of construction that unless paid up in full at

once, and more regularly in future, they would do no more work. They

also openly stated their intention of committing acts of violence upon

the staff of the road, and to destroy property. I received a deputation

of the ringleaders, and assured them that <f they committed any act of

violence, and were not orderly, in the strictest sense of the word, 1

would inflict upon the offenders the severest punishment the law would

allow me. They saw the manager of construction, who promised to accede

to their demands, as far as lay in his power, if they would return to

their camps, their board not to cost them anything in the meantime. Some

were satisfied with this, and several hundred returned to their camps.

The remainder stayed at the Beaver (where there was a population of 700

loose characters), ostensibly waiting for their money. They were

apparently very quiet, but one morning word was brought to me that some,

of them were ordering the bricklayers to quit work, teamsters freighting

supplies to leave their teams, and bridgemen to leave their work. I sent

detachments of police to the points threatened, leaving only two men to

take charge of the prisoners at my post. I instructed the men in charge

of the detachments to use the very severest measures to prevent a

cessation of the work of construction.

"On the same afternoon.

Constable Kerr, having occasion to go to the town, saw a contractor

named Behan, a well known desperado (supposed to be in sympathy with the

strike), drunk and disorderly, and attempted to arrest him. The

constable was immediately attacked by a large crowd, of strikers and

roughs, thrown down and ultimately driven off. He returned to barracks,

and on the return of Sergeant Fury, with a party of three men from the

end of the track, that non-commissioned officer went with two men to

arrest the offending contractor, whom they found in a saloon in the

midst of a gang of drunken companions. The two constables took hold of

him and brought him out, but a crowd of men, about 200 strong, and all

armed, rescued hi ml in spite of the most resolute conduct on the part

of the police. The congregated strikers aided in the rescue, and

threatened the constables if they persisted in their efforts.

"As the sergeant did

not desire to use his pistol, except in the most dire necessity, he came

to me, (I was on a sick-bed at the tune) and asked for orders. I

directed him to go and seek the offender, and shoot any of the crowd who

would interfere. He returned, arrested the man, but had to shoot one of

the rioters through the shoulders before the crowd would stand back. 1

then requested Mr Johnston, to explain the Riot Act to the mob, and

inform them that I would use the strongest measures to prevent any

recurrence of the trouble. I had all the men who resisted the police, or

aided Behan, arrested next morning, and fined them, together with hnn,

S100 each, or six months hard labour.

"The strike collapsed

next day. The roughs having had a severe lesson, were quiet. 1 he

conduct of the police during this trying occasion was all that could be

desired. There were only five at the Beaver at the time, and they faced

the powerful mob of armed men with as much resolution as if backed by

hundreds.

"While the strike was

in progress I received a telegram from His Honour the

Lieutenant-Governor of the Xorth-West Territories, directing me to

proceed to C'algarv at once with all the men, but in the interests of

the public service I was obliged to reply, stating that to obey was

impossible until the strike was settled.

"On the 10th day of

April the labourers had been all paid, and I forthwith proceeded to

Calgary, leaving the men in charge of Sergeant Fury until everything was

perfectly satisfactory."

On the 7th of April,

this year, a constable found in the Moose Jaw Creek the dead body of a

man named Malaski, with a heavy chain attached. The same night Sergeant

Fyffe arrested one John Connor on suspicion of being the murderer. An

examination of Connor's house showed traces of blood on the walls and

floor, an attempt having been made to chip the stains off the latter

with an axe, and further examination revealed the track of the body,

which had been dragged from the house to the creek.

The murder had

evidently been committed with an axe, while the murdered man was lying

on the bed, probably asleep, there being three deep wounds on the side

of the head. Connor was convicted of the murder before Colonel

Richardson, Stipendiary Magistrate, and a jury, on the 2nd May, and was

executed at Regina on the 17th July. The prisoner made no statement of

any kind with respect to his guilt.

During the construction

of the prairie sections of the C. P. R. the duties of railway mail

clerks in the North-West were performed by members of the force. During

1884, from Moose Jaw westward, all the mail via the Canadian Pacific

Railway was conveyed to and fro in charge of members of the force, their

number varying with the alteration in the train service. Three

constables from headquarters performed this duty between Moose Jaw and

Medicine Hat, two of the Maple Creek division from Medicine Hat to

Calgary, and two of the Calgary division from that place to Laggan.

These men were sworn as

officials of the Postal Department, and in the absence of aught to the

contrary, carried out their duties to the satisfaction, no less of the

Postal Department, than of their own officers.

In his annual report

for 1884 the Commissioner pointed out the need of a further increase in

the number of non-commissioned officers and men in the force, to enable

him to comply with the daily increasing requirements of advancing

settlement and civilization. Colonel Irvine suggested that 300

additional men should be obtained as soon as possible, these to be

recruited in Eastern Canada, and to be men of undeniable physique and

character, accustomed to horses, and able to ride. With such men, the

Commissioner explained, the necessary training, including a course of

instruction in police duties, could be more rapidly completed than if

equitation, in addition to the rudiments of foot and arm drill, had to

be taught.

We obtain a good idea

of the class of men composing the North-West Mounted Police at this time

from a very readable and well written book published by Sampson Low &

Co., London, 1889, entitled "Trooper and Redskin in the Far North-West;

Recollections of Life in the North-West Mounted Police, Canada, from

1884 to 1888," by John G. Donkin, late Corporal X. W. M. P. The author,

in a chapter directly concerning the personnel of the Mounted Police

wrote: "After having been about two months in the corps, I was able to

form some idea of the class of comrades among whom my lot was cast. I

discovered that there were truly "all sorts and conditions of men." Many

I found, in various troops, were related to English families in good

position. There were three men at Regina who held commissions in the

British service. There was also an ex-officer of militia, and one of

volunteers. There was an ex-midshipman, son of the Governor of one of

our small Colonial dependencies. A son of a major-general, an ex-cadet

of the Canadian Royal Military College at Kingston, a medical student

from Dublin, two ex-troopers of the Scots Greys, a son of a captain in

the line, an Oxford B. A., and several of the ubiquitous natives of

Scotland, comprised the mixture. In addition, there were many Canadians

belonging to families of influence, as well as several from the

backwoods, who had never seen the light till their fathers had hewed a

way through the bush to a concession road. They were none the worse

fellows on that account, though. Several of our men sported medals won

in South Africa, Egypt, and Afghanistan. There was one, brother of a

Yorkshire baronet, formerly an officer of a certain regiment of foot,

who as a contortionist and honcoinique was the best amateur I ever knew.

There was only an ex-circus clown from Dublin who could beat him. These

two would give gratuitous performances nightly, using the barrack-room

furniture as acrobatic properties."

This aggregation of

"all sorts and conditions of men," already proved to be efficient in

many a tight corner, was about to undergo the supreme test of service in

actual warfare. |