I

'S ann as an tir's 'eachdraidh a chineas spiorad

cogail

The military spirit comes out of the land and its history

Ever since the first disbanded Highland soldiery and

displaced crofters settled on Canada's shores two hundred years ago, in

the 1760s and 1770s, Scottish Canadians have borne their full share of

the burden of Canada's defence. Soldiers and regiments bearing Scottish

names and wearing the bonnet, kilt and feather form a mighty array in

our history; they have fought in the snows of Canada, in the mud of

Flanders, in the mountains of Italy; they have inspired Canadians with

the military traditions of old Scotland, bravery and devotion, fortitude

in distress. Today there are over 2,000,000 people of Scottish descent

in Canada, although through intermarriage the Scottish blood flows in

the veins of many more Canadians than the census returns would suggest.

It is, indeed, sufficiently widespread that, despite dilution, it has

encouraged that mystic sympathy of Canada for Scotland which unites the

two lands in the unity of understanding. The Canadian soldier in World

War II was well aware of it, if only because

he seemed to feel more at home in Scotland than in the land of the

Southrons. Perhaps that understanding derives, in part at least, from

the fact that Canadian and Scot live in northern lands, to the south of

which there is a powerful, and too often dominating nation. Each knows

that his nation has always to be on the watch lest it lose its freedom

and its own distinctive nationality.

The Scottish military tradition is generally

associated with the Highlands, the country of the chief, clan and

cateran. This does not mean that the Lowlands were bare of men of

military virtue, of men ready and able to wield a spear or broadsword in

defence of their faith and their possession - the achievements of the

Cameronians contradicts that - but rather that the Highlands, by the

very nature of the countryside and the tribal feudalism

it nourished, tended to develop and perpetuate the military

characteristics of independence and combativeness more than did the land

and society of the Lowlands.

The country north and west of the Highland Line was,

and still is, in many respects, a wild, harsh, forbidding land of

violent tempests and uncertain climate. It is not a rich luxuriant land,

but one of bare mountains, bleak hills, heathered moors, coniferous

forests, lakes, streams and fens. There are only isolated and

disconnected patches of arable soil1

located in the sequestered straths, glens and islands which favoured the

settlement of family groups under their natural leaders or ceann-cinnidh.

Such a land was not of the nature to sustain a large and prosperous

agricultural population. The men who lived in the Highlands were the

sons of Esau. They lived on the fish they caught in the lochs, the deer

they hunted in the hills, and the herds they tended on their thin

mountain pastures or reaved from their Lowland neighbours. Only the

bold, the strong, the hardy and the independent survived in such a land,

men nursed in poverty, men whose needs were simple and basic. Geography

made the Scottish Highlander, and it made him good soldier material,

because it demanded those qualities which make men good soldiers;

hardihood, courage, endurance, self-reliance and loyalty to one's leader

and one's comrades.2

The history of the country, too, added its strength

to reinforce the fighting spirit of the men of Scotland. From the day

when Calgacus fell at the head of the Pictish host to the Roman,

Agricola, at Mons Graupius in 84 A.D., to the flight of Charles Edward

Stewart from the field of Culloden in 1746, Scottish history has been

one long, bloody brawl. But Culloden was the end - the end of seventeen

centuries of strife between warring tribes, warring religions, warring

nations. Did anything of value emerge from it beyond an unpopular union

with England bought with English gold? Does anything emerge from

Scottish history other than bloodshed and violence and sticky sentiment?

Beneath the surface will be found virtues as heroic as they sometimes

appear irrational, the virtues of independence, devotion and valour.

These are the saving virtues of the Scottish story and the backbone of

the Scottish military tradition.

II

Na Sassunaich a ghadhail cothrom air spiorad cogail na

Ghaidhail

The Southrons exploit the Scottish military spirit

The immediate British reaction to the Jacobite rising

of 1745-46 was an effort to break the spirit of the men who had served

the Jacobite cause. Rapine, slaughter and torture, all were used with

relentless vindictiveness by the king's son who commanded the British

government forces.3 Quarter was given

to no straggler or fugitive, except to the select few reserved for the

spectacle of a public execution. For the wounded who lay on the field of battle there was no compassion,

only the bullet and the bayonet when they were discovered. All men

suspected of rebel sympathies were herded into gaols, prison ships,

cellars or lofts, and left without food or water, or clothes to hide

their nakedness; even the doctor had his lancet taken from him lest he

be moved to blood some of the wounded in order to save their lives. To

His Grace of Newcastle, Lord Chesterfield wrote, "Starve the country by

your ships, put a price on the heads of the chiefs, and let the Duke put

all to the fire and sword."4 That was

exactly what "Bloody Butcher" Cumberland did. Through the glens and over

the hills, his patrols laid waste the land, plundered the houses, burned

the crofts, killed suspected Jacobites, raped the women and drove the

Highlanders' cattle to the military posts. When starving creatures

sought a handful of oatmeal they were driven away with the butts of

muskets; should any soldier or his wife show a little humanity, well,

Cumberland had said "they shall be first whipped severely . . . and then

put on meal and water in the Provost for a fortnight."5

Heartless and abhorrent as these reprisals were, the Duke considered

them inadequate. To Newcastle he wrote, three months after the battle of

Culloden, "I am sorry to leave this country in the condition it is in;

for all the good that we have done is a little blood letting, which has

only weakened the madness, but not at all cured it; and I tremble for

fear that this vile spot may still be the ruin of this island and of our

family."6

Such methods were not without results; but even more

effective in throttling the Highland spirit were the legislative

enactments, the laws that destroyed the clan system, that made the

playing of the old music and the wearing of the kilt and tartan criminal

offences. Every Highlander was required to surrender his arms. Failure

to do so might mean transportation for seven years. Restrictions too

were imposed upon the Episcopal Church, regarded by the authorities as

only slightly less ardent than the Roman Catholics in their support of

the House of Stewart. Most effective of all was the Act abolishing the

hereditary jurisdictions. For generations the inhabitants of the

Highlands had looked to their chiefs for direction and protection. Now

there were no more chiefs. Those who had supported the Jacobites in 1745

were, in some instances, executed, in others, outlawed, and in all

instances obliged to forfeit their estates. Those who had not been out

in '45 were ready to sell out, salvage what they could in golden

guineas, as compensation for what they had lost in giving up their

rights of "pit and gallows." They moved to Edinburgh and acquired an

English veneer. Thus, when he needed him most, the Highland clansman had

no chief. He was leaderless in a hostile world.

Two choices were open to him if he were to avoid

starvation. He could emigrate, leave the land of his forefathers and

find a new home elsewhere, or he could accept German Geordie's shilling

and serve in the army of the Hanoverian king. Both were unpalatable. But

the will to survive is stronger even than love of home or pride of

ancestry.7

Poverty was nothing new to the Highlander. Neither

was serving in the armies of foreign monarchs. He had

been doing it since the days of the Crusades. During the sixteenth

century licences had been granted to individuals to raise men in

Scotland for service in Denmark, Sweden and the Low Countries, a traffic

which increased during the seventeenth century. Donald MacKay raised

3600 men for Christian IV, and Gustavus Adol-pus

is said to have had 10,000 Scots under his command during the Thirty

Years' War. Others served the King of France as Archers of the Guard. At

a later date refugees from the forces of Dundee, Mar and Charles Edward

fought in the armies of France. The son of a Scottish Jacobite

schoolteacher became a marshal of France under Napoleon,

Etienne-Jacques-Joseph-Alexandre Macdonald, Duke of Taranto.

There was precedent too for serving King George. In

1725 the British government had raised a number of independent companies

to keep watch on the Highland clans and discourage the popular

activities of cattle lifting and blackmailing. These independent

companies were clad in a black, green and blue government tartan to

distinguish them from the regular troops and were known as the

Freiceadan Dubh, or Black Watch. Several years later, in the hope of

discouraging the growth of Jacobitism, the Lord President Duncan Forbes

of Culloden suggested to the British authorities that greater scope

might be given the natural military attributes of the Highlanders were

they to be recruited into several regiments commanded by English or

Scottish officers "of undoubted loyalty" and officered by chiefs and

chieftains "of the disaffected clans." "If Government pre-engage the

Highlanders in the manner I propose," he wrote, "they will not only

serve well against the enemy abroad, but will be hostages for the good

behaviour of their relatives at home, and I am persuaded it will be

absolutely impossible to raise a rebellion in the Highlands."8

Forbes's advice was followed only in

part. Not several but one regiment only was formed, and this by bringing

together the various independent companies of the Watch. In 1740 the new

regiment, numbered the 43rd (changed in 1749 to the 42nd) but still

bearing the name Black Watch, was embodied under the command of Sir

Robert Munro of Foulis, and officered by Highland gentlemen, a number of

whom were from the clans Munro, Grant and Campbell, whose Whig

sympathies met with the approval of the British government.9

In 1743 the Black Watch was ordered to England. It

was not a popular order, nor a popular move; the Highlanders had no wish

to serve so far from their own glens. However, they were told that the

move was simply to satisfy the curiosity of the German lairdie who sat

on England's throne and who had never seen a Highland regiment. When

they arrived in London the soldiers of the Black Watch learned that the

king had gone to Hanover and heard rumours that they were to be sent to

America. Regarding such deception as intolerable - many of those even in

private rank were gentlemen - they set out on their own for Scotland.

Overtaken at Northampton by a larger British force, the Scots

surrendered and were disarmed. A number of the so-called mutineers were

tried; three of them (all sons of Clan Chattan) were executed. Then the

expected blow fell, two hundred of the Watch were sent to the West

Indies; the remainder joined Cumberland's forces in Flanders, to

contribute their decisive strength to the victory of Fontenoy. During

the Jacobite rising of 1745-46 the Black Watch warmed their heels on the

shores of Kent; to send them north against their blood relatives in the

Highland host would hardly have been a politic act. After Culloden, they

went to Ireland on garrison duty where they remained, with one short

tour in Flanders, until the outbreak of the Seven Years' War against

France in 1756.

The bravery of the Watch at Fontenoy had made its

impression upon the British authorities. They therefore decided to

repeat the experiment of employing Highlanders in the British service.

In 1745 Campbell, the Earl of Loudoun, was commissioned to raise another

Highland unit.10 The time, however, was

critical, and the devotion of the recruits to the Hanoverian monarchy

suspect. There were desertions to the Jacobites, but for the most part

the officers and men remained true to their engagement. Nevertheless the

regiment did not see service as a unit. Three companies were at

Prestonpans only to surrender to Prince Edward when Cope's army was put

to flight. Some men of Loudoun's regiment were victims of the Rout of

Moy. Three companies were at Culloden. After a brief tour in the Low

Countries the regiment was disbanded in 1748.

It was the outbreak of the Seven Years' War with

France in 1756 that led to the policy which drained the Highlands by

sending Scotsmen to fight England's wars in Europe and North America.

William Pitt adopted Duncan Forbes's ideas with enthusiasm, and during

the period of the Seven Years' War no fewer than ten line regiments, the

77th (Montgomery's), 78th (Fraser's), 87th (Keith's), 88th (Campbell's)

89th (Gordon's), 100th, 101st (Johnstone's), 105th (Queen's), 113th

(Royal Highland Volunteers), and MacLean's, and two fencible regiments

(regiments for the internal defence), Argyll Fencibles and Sutherland

Fenci-bles, were recruited in the British interest.11 From

Britain's point of view it was sound military strategy to make the best

use of the Scottish military tradition, and good politics to get so many

sullen and resentful unemployed men out of their mountain fastness. It

was a policy which lesser men than Pitt were glad to continue when later

wars broke out in 1775 and 1793. The regiments raised during the

American Revolutionary War included 71st (Fraser's), 73rd (MacLeod's),

74th (Argyll Highlanders), 76th (Macdonald's), 77th (Atholl

Highlanders), 78th (Seaforths), 81st (Aberdeenshire Regiment), 2nd

Battalion, Black Watch. Additional regiments were raised on the outbreak

of the French Revolutionary War in 1793. The depopulation of the

Highlands may have been largely the result of the Highland clearances

and the emigration of the clansmen; but it was the result, too, of the

military exploitation of Scotland's human resources for the sake of

Britain's imperial ambitions. Of Britain's new Highland

regiments, three saw service in North America during the French war, the

42nd (Black Watch), the 77th (Montgomery's), and the 78th (Fraser's).

The two latter were raised in 1757 from the Jacobite clans, Frasers,

Macdonalds, Camerons, MacLeans and Macphersons in particular. The 77th

was commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Archibald Montgomery, afterwards

Lord Eglinton, and the 78th by Simon Fraser, son of the Lord Lovat who

had lost his head after Culloden for supporting Prince Charles.

The 42nd was the first Highland regiment ever to come

to North America. It arrived in New York in 1756 and promptly moved to

Albany. During the winter of 1756-57 it underwent serious training in

bush fighting in the Canadian manner. It was a kind of training much

needed by the Scots, for their traditional tactic of firing a volley and

then rushing forward with targe and broadsword to engage the enemy

hand-to-hand was of limited value against an elusive foe who knew how to

make good use of cover. Early in the summer of 1757, the regiment moved

to Halifax as part of the large force assembled for an attack upon

Louisbourg. Here it was joined by the 77th and the 78th. The Louisbourg

assault was not carried through in 1757. The delay in the arrival of the

naval component, the lateness of the season, and the arrival of

reinforcements in Louisbourg convinced Loudoun that the assault would

have to be postponed to a more opportune occasion and, leaving a number

of his troops at Halifax, he returned to New York with his three

regiments of Highlanders.

All three regiments played notable roles during the

campaign of 1758, albeit in three separate theatres of operations.12

In the spring, Fraser's Highlanders

joined Amherst's force for the postponed assault upon Louisbourg,

forming part of the brigade commanded by Brigadier-General Wolfe, who,

incidentally, had fought at Culloden and had shared in the ruthless and

unsavoury "pacification" of the Highlands. But Wolfe, who had formerly

distrusted the Highlanders, now recognized their worth, and used them

along with the light infantry in every action calling for the employment

of shock troops. After a siege of seven weeks the fortress surrendered.

The impatient Wolfe would have continued on to Quebec, but he was

compelled to limit his military activities to attacking Acadian

communities along the Atlantic shore.

On the far western front, Montgomery's Highlanders

pushed their way slowly towards Fort Duquesne as the main regular

component of Brigadier General Forbes's corps. At Loyalhanna, about 40

miles from their destination, the Highlanders' weakness in bush fighting

became all too apparent when a detachment of the 77th, under Major James

Grant, was badly cut to pieces by the French and the Indians. But the

French at Fort Duquesne, outnumbered and in no position to offer a

prolonged resistance to Forbes's men, in November blew up their defences

and withdrew. In honour of William Pitt, Forbes renamed the smoking ruin

Pittsburgh. Here the 77th spent the winter. In the following May it

moved to the central theatre of operations to join the 42nd on Lake

Champlain for a second attack upon Carillon (Ticonderoga).

The first assault upon the French position at

Carillon had ended in disaster for the Black Watch. With every

confidence in the world, the Highlanders had joined the mighty array

which was intended to strike north to the St. Lawrence - 16,000 men,

regulars, provincials, rangers and boatmen. What was there to halt them?

Only a poor stone fort on Lake Champlain manned by a force considerably

inferior in numbers. The British commander, James Abercromby, had all

the tools necessary for siege or open warfare. A quick look at the

French defences convinced him that Carillon could be carried by storm,

and, with a singular lack of imagination, he decided upon a frontal

attack. On the morning of July 8 the British assault troops, led by the

Grenadiers, deployed in the open area in front of the French defences;

four battalions, with the 42nd in support. When the Grenadiers failed to

penetrate the thick abbatis in front of the French breastworks, the

Scots impetuously rushed forward and began hacking their way through the

tangled branches. Safe behind their defences the French infantry cut

them to pieces with well-directed musketry. Time and again the brave

Highlanders surged forward, only to fall back in the face of a murderous

fire. A few men did succeed in reaching the French breastworks, but they

had no scaling ladders and when, after great exertion, Captain John

Campbell and several others forced their way over the French works, they

were stabbed to death by French bayonets. For four hours Abercromby kept

it up; then, finally, he gave the order to retreat. Despite their

losses, the Highlanders still sought vengeance for the death of their

comrades, and Abercromby was obliged to repeat his orders three times

before he could prevail upon the stubborn Scots to obey. The 42nd,

indeed, paid dearly for its intrepidity: 314 officers and men were

killed and 333 wounded in the battle, over half the strength of the

regiment. Despite its shattered condition Abercromby gave The Black

Watch the honour of covering the retirement, although in its weakened

state it is questionable whether the regiment could have beaten back a

determined attack had Montcalm been disposed to pursue the retreating

British. Abercromby may not have been a brilliant tactician, but at

least he knew how to humour the spirit of his Highlanders.

1759 was the decisive year of the war, and to the

British success in that year the Highlanders made a notable

contribution. The Black Watch, reinforced by a strong infusion of new

recruits, and Montgomery's Highlanders formed part of the army Jeffrey

Amherst led, methodically and laboriously, through the Lake George-Lake

Champlain entrance to Canada. Carillon and Fort St. Frederic (Crown

Point) were occupied without a battle. Had Amherst been less concerned

with rebuilding what the French had destroyed, he might have reached

Montreal and the St. Lawrence. As it was he got no further than Crown

Point before going into winter quarters. Thus it was Fraser's

Highlanders, not the 42nd or the 77th, which played the major role in

the reduction of Canada.

Occupying a position made formidable by nature and by

military engineering, Quebec was the key to Canada. Montcalm realized it

and chose to remain on the defensive. Let the British come to him. They

did, in the spring of 1759, under James Wolfe. But weeks went by and

Wolfe made little or no progress. Fraser's men shared in the ill-fated

attack on the French and Canadian position at Beauport in July, and in

the terrorist raids carried on by General Wolfe during the month of

August. Finally, almost as a last resort, Wolfe sought to gain a

lodgement to the west of the city on the Plains of Abraham. Fraser's

Highlanders were on the heels of the Light Infantry who first climbed

the cliff of Quebec in the early hours of September 13. A

French-speaking Highlander, Captain Donald Macdonald, a brother of

Clanranald, whose men had been out in '45, lulled the suspicions of the

French sentry and made possible the seizure of the plains. When the

British drew up their battle array, Fraser's were in the front rank.

After exchanging shots with the French, the Highlanders reverted to

their traditional tactics; they threw away their muskets, drew their

broad swords and swept forward, halting only when they reached the walls

of the city. Led by Brigadier-General Murray, they returned to the woods

on the left flank to oust the Canadians holding up the other pursuing

troops. Watching the whole thing with great interest was Montcalm's

aide-de-camp, the Chevalier Johnstone.13 He, too, had been out in '45, fighting alongside the

Glengarry Macdonells at Culloden. He would have recognized the names if

not the features of those who were killed or wounded at Quebec, such as

McNeil of Barra, Macdonell of Lochgarry, Macdonell of Keppoch, Fraser of

Inverlochy and Campbell of Barcaldine.

Fraser's Highlanders witnessed the surrender of

Quebec on September 18 by de Ramezay, a Frenchman of Scottish descent,

and then spent the winter in the ruined city. It was dreadfully cold,

cold enough to cause Malcolm Fraser to admit that "the Philibeg is not

at all calculated for this terrible climate."14 Canada was colder even than Scotland. In the spring the

78th marched out with Murray to face the French and Canadian army, led

by the Chevalier de Levis. Murray was defeated at Ste. Foye, a mishap

which elicited from Charles Stewart, who had served at Culloden, "from

April battles and Murray generals, good Lord deliver me!`15

Only the walls of Quebec and the timely arrival of British ships of war

saved Murray from surrendering in 1760 the fortress Wolfe had gained in

1759.

Following the capitulation of Canada in September,

1760, the Black Watch and the 77th were sent to the West Indies.

Subsequently they returned to assist in the suppression of the Indian

rising led by Pontiac. Meanwhile, the 78th contributed a detachment to

Colonel William Amherst's force, sent to recover St. John's,

Newfoundland, from the French in 1762. In 1763 the war was over and the

peace was signed. The Watch remained on the regular establishment, but

the 77th and 78th were ordered to be disbanded, the officers and men

being given the opportunity of settling in British North America if they

wished to do so. Rather than face sad memories and unemployment in

Scotland, many chose to remain in Canada, where each officer and man

received a grant of land according to his rank. Thus the disbanded

solidiery of Montgomery's and Fraser's Highlanders became the first

Scots to form an integral part of Canadian life and history. And they

were not the last. Others soon arrived in North America; destitute but

proud men, who settled in Prince Edward Island through the initiative of

John Macdonald, Eighth of Glenaladale; in Pictou, Nova Scotia, through

the inducements of a Lowland promoter; and the Mohawk Valley, through

the leadership of three Macdonell lairds, Aberchalder, Leek and

Collachie. By far the greater number of them were Jacobites: "ged chaidh

an sgadpdth air gach taobh, cha chaochail iad an gnaths," sang the

Gaelic bard.16 "Although they were scattered in every

direction, they did not change their ways."

III

Spiorad

cogail na Ghadhail a

tighinn do Chanada

The Scottish military spirit comes to Canada

Vergennes, the astute French ambassador to

Constantinople, is said to have predicted that England would quickly

repent having insisted upon the cession of Canada by France, if only

because it removed the American colonies' greatest inducement to remain

within the British Empire, the threat of French invasion. Peter Kalm had

said much the same thing twelve years before. Within another twelve

years, history proved both good prophets. By 1775 British soldiers and

American minutemen were exchanging shots at Lexington and a British

garrison was being besieged at Boston by 20,000 angry American militia.

In 1776 the American colonies declared their independence.

Once more the British government looked to the Scots

for help. More regiments were raised in Great Britain and old ones, like

Fraser's, were revived. More significantly, the practice of employing

Scotsmen as soldiers was extended to the British possessions in North

America. On June 12, 1775, General Thomas Gage issued orders to

Lieutenant-Colonel Allan Maclean, son of Maclean of Torloisk, Mull, to

raise a regiment consisting of two battalions, each of ten companies, to

be clothed, armed and accoutred like The Black Watch17 and "to be called the Royal Highland Emigrants."18

Maclean was appointed lieutenant-colonel commandant of the regiment, as

well as commanding officer of the 1st Battalion, with Donald Macdonald

as his major, while Major John Small, formerly of the 42nd, was placed

in charge of the 2nd battalion.

The idea was that The Emigrants should find their

recruits among former soldiers who had served in the 42nd, the 77th and

the 78th, and in the several Scottish settlements in America. As

inducements to enlist, each man was promised a grant of land at the

expiration of hostilities, and one guinea levy-money on joining. Even

so, recruits came in slowly. The recruiting parties of the 1st Battalion

found it difficult to get recruits safely and quietly out of the Mohawk

Valley without arousing the suspicions of Americans, and

it was some time before The Emigrants were brought up to strength. To

fill the gaps in the ranks, recourse was had to enlisting Irishmen from

Newfoundland and prisoners of war who were willing and ready to change

sides. Few of these latter were Scots, and few of them made reliable

soldiers.19 Initially,

detachments of The Emigrants were posted along the St. Lawrence and in

the Richelieu Valley and, under Maclean's command planned to relieve the

besieged Fort Saint Jean. With the defeat of Guy Carleton's co-operating

force from Montreal, Maclean hurried his Emigrants back to an almost

defenceless Quebec where they furnished the bulk of the "regular" (if

they could be called that) army of the garrison. During the siege of

Quebec by Montgomery and Arnold, The Emigrants played a notable part.

Captain Malcolm Fraser, formerly of the 78th, was the first to observe

the American signals on the night of December 31, 1775, indicating that

an attack was in the offing. Allan Maclean commanded the defenders under

Carleton and was, in large measure, responsible for the defeat of the

Americans.20 When General Burgoyne organized his

counter-attack force in 1777, Maclean's Emigrants were posted along the

line of communications and provided the garrison for Fort Ticonderoga.

As an indication of his satisfaction with their services, George III

instructed Sir Frederick Haldimand in 1779 to place The Emigrants upon

the regular establishment of the British army and to number them the

84th among the British line regiments.21 During its career

the 1st Battalion in Canada was plagued with desertions, mostly among

the Americans and Irish who had joined the regiment; it is worth noting

that not one native Highlander deserted, and only one man was brought to

the halberts during the time the regiment was embodied.22

In Nova Scotia, Major Small had less trouble

obtaining recruits than Maclean in Canada. The 2nd Battalion was not,

however, employed as a unit. Instead, it was broken up into detachments

and sent to garrison such posts as Annapolis, Cumberland, Saint John,

Windsor and Halifax, where American raiders might be expected to land.

The rest of the battalion, five companies, was sent to join Cornwallis

in the southern colonies where they fought with distinction at Eataw

Springs. The troops, however, resented being used piecemeal. It was with

disgust that Captain Alexander Macdonald wrote, "We have absolutely been

worse used than any one Regiment in America and have done more duty and

drudgery of all kinds than any other Battalion in America, these three

Years past, and it is but reasonable, Just and Equitable that we should

now be Suffered to Join together at least as early as possible in the

Spring and let some Other Regiment relieve the different posts we at

present Occupy."23

Both battalions of The Royal Highland Emigrants were

disbanded at the end of hostilities. Some of the officers and men

returned to Scotland, but the greater number took up their promised land

grants, the 1st Battalion in Canada and the 2nd in Nova Scotia, and

remained in British North America.

There were other Scotsmen who served the King in

British North America during the Revolutionary War besides those

commissioned or enlisted in the Royal Highland Emigrants. A considerable

number of Highlanders from Glengarry, Glen Urquhart and Strathglass had

emigrated during 1773 to the Mohawk Valley and settled on the lands of

Sir William Johnson, the Irish baronet, whose name was so closely

associated with the league of the Six Nations. Johnson liked the

Highlanders, cultivated them, and encouraged them to maintain their

customs. The tradition of the clan and the chief was still very much

alive among the Highlanders, and it was hardly surprising that Johnson

assumed, in the minds of his Scottish tenantry, something of the

character of a Highland chief. When Sir William died in 1774, this

attachment was transferred to his son, Sir John. This explains why, on

the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, when Sir John Johnson fled to

Canada early in 1776, he was accompanied by a considerable number of his

Highland followers. These were joined a year later by the remainder of

the Mohawk Valley Highlanders.

Scarcely had Johnson put a foot in Montreal when he

received a commission as colonel in the British army, and was authorized

to raise a regiment of Loyalists under the name of The King's Royal

Regiment of New York (KRRNY).24 With

his tenantry at his heels he had no problem in finding recruits,

particularly when he had the support of the Macdonell chieftains,

Aberchalder, Scotus and Leek, as his officers.

The 1st Battalion of the KRRNY saw action with St.

Leger's force in 1776 when they defeated the Americans at Oriskany.

However the failure to capture Fort Stanwix nullified this victory and

St. Leger did not join forces with Burgoyne. In the years which

followed, the "Royal Yorkers," as they were sometimes called, took part

in several notable raids into the Mohawk Valley. These actions not only

brought in additional recruits to the Yorkers, but also stripped the

region of supplies useful to the American rebels. Accordingly, Johnson

was authorized to form a 2nd Battalion in 1780,25 despite the fact that Canada's Swiss governor, Sir

Frederick Haldimand, was disposed to sneer at Johnson's regiment as "a

useful corps with the Ax," but "not altogether to be depended on with

the Firelock."26

Like the Royal Highland Emigrants, the officers and

men of the KRRNY were given land grants on demobilization in 1783. The

1st Battalion settled largely in what is now Glengarry and Stormont

counties; the 2nd Battalion, which contained fewer Scots and more

Germans, settled in the Bay of Quinte region.

During the American invasion of Canada at the time of

the War of 1812, few Scotsmen from Great Britain saw service in this

country. With the exception of the Royal Scots, no overseas Scottish

units were sent to Canada until the late summer of 1814, when the

Glasgow Lowland Division arrived from Ireland. And in the Royal Scots

few of the men were, in fact, Scottish-born; most of them were of

English, Irish and French nationality. The Scots who fought in the

Canadian War of 1812 were, therefore, most of them Canadian Highlanders

who lived on the banks of the St. Lawrence River, where

the disbanded Emigrants and Royal Yorkers had settled a generation

previously, and where their numbers had been reinforced by the arrival

from Scotland of the disbanded Glengarry Fencibles and their chaplain,

Father Alexander Macdonell, in 1803.

Several times during the early years of the

nineteenth century, suggestions had been put forward that a regiment of

Canadian Highlanders should be raised as a force to supplement the

British regulars. But no one had heeded this advice until the threat of

war with the United States was so obvious that it could be ignored only

with peril. Finally, under the shadow of invasion, the Glengarry

Regiment of Light Infantry Fencibles was embodied in Upper Canada early

in 1812. Father Alexander Macdonell, assisted by "Red George" Macdonell

of Leek, fired the heather, and on May 12 a unit of some 400 men was

paraded for duty, just one month before the President of the United

States declared war on Great Britain and began to move troops towards

the Canadian frontier. The Glengarrians shared in many of the

significant engagements of the war, including Salmon River, Ogdensburg,

York, Fort George, Sackett's Harbour, Oswego, Fort Erie, Lyon's Creek

and Mackinac, as well as in the hardest fought battle of the war,

Lundy's Lane, where they protected the right flank of the British force

and were accorded the right to wear "Niagara '' on their colours. In

1816 the regiment was disbanded at Kingston.

The men from the Scottish counties also saw service

in the militia. In General Brock's opinion the militia along the St.

Lawrence, from the Bay of Quinte to Glengarry, were "the most

respectable of any in the province,"27 a statement borne out by the battle honours awarded the

militia regiments from Glengarry, Stormont and Dundas. The 1st Stormont

Regiment was at Salmon River, Ogdensburg, Crysler's Farm, and Hoople's

Creek, and the 1st Dundas at Toussaint's Island, Prescott, Salmon River

and Ogdensburg. Militiamen from these counties were also employed in

garrison and escort duty along the vital highway of the St. Lawrence,

the sole line of communication between Upper and Lower Canada.

The significant role of the Scots in the militia

during the War of 1812 is revealed by a glance at the names of the

officers who commanded the county units.28 Among them we find Colonel Neil Maclean, a former Royal

Highland Emigrant, of the 1st Stormont; Colonel William Fraser of the

1st Grenville; Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Fraser of the 1st Dundas;

Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander MacMillan of the 1st Glengarry; and

Lt.-Col. Allan Macdonell of Greenfield of the 2nd Glengarry.

Lieutenant-Colonel Allan Maclean of the 1st Frontenac became commanding

officer of the Battalion of Incorporated Militia. Lieutenant-Colonel

John Macdonell was A.D.C. to General Brock and died at Queenston Heights

with his superior officer. Colonel Archibald Macdonell commanded the 1st

Prince Edward Militia; Colonel John Ferguson, the 1st Hastings; Colonel

Matthew Elliott, the 1st Essex; Lt.-Col. William Graham, the 1st York;

and Captain William Mackay, the Michigan Fencibles. Mackay and Elliott

were officers of the Indian Department. The Adjutant-General of the

Canadian militia during the war was

Major-General Aeneas Shaw, a former officer of The Queen's Rangers.

The response of the Canadian Scots to the call to

arms was reminiscent of the old days in Scotland, and it was repeated

with the mustering of the militia during the troubles of 1837 and 1838.

If it was a Scot, William Lyon Mackenzie, who set out to establish a

Canadian republic in December, 1837, it was another Scot, Sir Allan

MacNab, who led the Loyalists who opposed him. In the Ottawa Valley, the

last Highland chief ever to play the traditional role, Archibald MacNab,

12th of MacNab, raised the local militia in Lanark and Renfrew; and in

Glengarry, Bishop Alexander Macdonell prompted the Highlanders to form

four battalions, one each from the townships of Charlottenburg,

Lancaster, Lochiel and Kenyon, commanded by Colonels Alexander Fraser,

Donald MacDonald, Alexander Chisholm and Angus Macdonell respectively.

In November, 1838, detachments of the militia from Stormont, Dundas and

Glengarry took part in the Battle of the Windmill, and other detachments

from the Glengarry and Stormont regiments formed part of Sir John

Colborne's corps employed in supressing the rebellion in Beauharnois. It

was not without justification that a British officer wrote in December,

1840, "I beg to state that the County of Glengarry has, on every

occasion, been distinguished for good conduct, and will, in any

emergency, turn out more fighting men in proportion to its population,

than any other in Her Majesty's Dominions."29

IV

That 'n

fhuil a tanachadh ach tha an spiorad treun

The blood grows thin but the spirit remains strong

Following the War of 1812 a number of Scottish line

regiments saw tours of garrison duty in Canada, including The Royal

Scots, the 71st Highland Light Infantry, the 70th Cameron Highlanders,

the 80th (Glasgow Lowland), and the 93rd Sutherland Highlanders. But the

days of the British garrison were numbered and by 1871 the last of the

British regiments had been withdrawn from Canada. The old county militia

units were also gone. In their place were the new volunteer territorial

units, which still form a considerable portion of Canada's present-day

military establishment. The Militia Acts of 1855 and 1859 provided for

the organization of volunteer regiments, and in November, 1859, the 1st

Battalion, Volunteer Militia Rifles of Canada, was organized in

Montreal. The following spring another battalion was formed, the 2nd

Battalion, Volunteer Militia Rifles, this time in Toronto. Thus began a

series of territorial infantry battalions which, prior to 1914, numbered

110.

The volunteer movement coincided, in date, with the

movement to eliminate the kilt as part of the military dress of British

regiments. Unable to find sufficient recruits in the

Highlands, the War Office had been compelled to fill the so-called

Scottish regiments with men of other nationalities, and the new recruits

were not only indifferent but sometimes hostile to the traditions the

kilt implied. With a home government cool towards the kilt it is hardly

surprising that few militia regiments in Canada were initially kilted

units. It was argued that Fraser's men had complained of the cold and

that the Glengarrians had willingly worn the uniform of the British

light infantry in 1812. Accordingly only two Highland units were

established, as such, in the 1860s and 1870s in Canada, both of them,

appropriately enough, in Nova Scotia: the 79th Colchester and Hants or

Highland Battalion of Infantry (later the Pictou Highlanders and today

the 1st Battalion Nova Scotia Highlanders), and the 94th Victoria

Highland Provisional Battalion of Infantry (later the Cape Breton

Highlanders and today the 2nd Battalion Nova Scotia Highlanders).30

But the kilt survived and was revived

in Great Britain in the 1880s, and in Canada the enthusiasm for the

Scottish military tradition was reflected in the formation of the 48th

Highlanders in Toronto in 1891; the 91st Highlanders (later the Argyll

and Sutherland Highlanders) in Hamilton in 1903; the 72nd Highlanders

(later the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada) in Vancouver in 1910; and the

79th Highlanders (later the Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada)

in Winnipeg in 1910. The 5th Battalion, organized in 1862 in Montreal,

was re-designated the Royal Scots Fusiliers in 1880. In 1906 it became

the Royal Highlanders of Canada, and in 1930, The Black Watch (Royal

Highland Regiment) of Canada.

Between 1899 and 1901 militia units provided men for

the Canadian battalions which served under British command during the

South African War, but it was not until the Great War of 1914-1918 that

Canadian troops were sent abroad in any very considerable numbers.

Following the declaration of war between Great Britain and Germany in

August, 1914, the Canadian Department of Militia and Defence, ignoring

existing militia units and the traditions they had developed, enlisted

men into a new series of numbered Canadian Expeditionary Force

battalions. Because the kilted units had demonstrated their popularity

in Canada, several of the CEF battalions were given Scottish

designations. It was almost as if Sir Sam Hughes and Sir Edward Kemp had

read the words of Duncan Forbes of Culloden or those of William Pitt.

Thus the 13th Battalion CEF carried the name "The Royal Highlanders of

Canada," the 15th CEF was the "48th Highlanders of Canada," and the 16th

CEF "The Canadian Scottish." These three Scottish units were grouped

together in the 3rd Canadian Brigade. The 42nd (Royal Highlanders of

Canada) and the 43rd (Cameron Highlanders of Canada) were in the 7th and

8th brigades; the 38th (Cameron Highlanders), the 72nd (Seaforth

Highlanders of Canada), and the 85th (Nova Scotia Highlanders) were part

of the 12th Infantry Brigade. None of these battalions, although they

carried Scottish names and their officers and men wore the kilt, were

composed solely of Canadian Scots or Scots living in Canada. If the 16th

Canadian Scottish was anything to go by, they included almost all the

nationalities one could find in Canada; Scots, of course, but also

English, Irish, French, Americans, Italians, Dutch, Danes, Mexicans and

others.31

The first major battle involving a Canadian Scottish

unit was a trying ordeal. When the French colonial troops broke under

the German gas attach at Ypres early in 1915, the 3rd Canadian Infantry

Brigade was left dangling at its flank. It was this brigade, with its

three Highland units, which bore the initial brunt of the German attack.

All three regiments suffered heavy casualties at Ypres and St. Julien,

but all proved their worth in battle. They had gone to France green and

untried. In the crucible of Ypres they became the veterans who gave the

Canadian corps its strength and its reputation.

Manifestly it is impossible to tell the whole story

of the Canadian Scottish battalions in World War I within the compass of

a few paragraphs. It is sufficient here to record the battle honours

worn by the Scottish units on their colours - household names to an

earlier generation and all too unfamiliar to those who have followed -

Festubert, Mount Sorrel, Somme, Courcellette, Arras, Vimy, Passchendaele,

Amiens, Hindenburg Line, Dro-court-Queant,

Canal du Nord, Valenciennes. These names echo through the halls of our

history the contribution made by the Canadian Scottish battalions,

indeed of all Canadian battalions, which fought under General Sir Arthur

Currie's command. And there is further testimony, too, of the prowess of

Canadian Scots. Should we forget the name of Sir Archibald Macdonell,

that descendant of the Glengarry Macdonells who commanded the 1st

Canadian Division? Should we forget the fact that eight of the Canadian

winners of the Victoria Cross between 1914-1918 were members of the

Highland battalions of the Canadian Corps? Such men as these walk erect

among the shades of those heroic Scots who, if not necessarily their

progenitors, were the inspiration of the tradition which the Canadians,

as members of Scottish units, had willingly embraced.

Perhaps it was the fighting reputation which the

Highland units earned during World War I; perhaps it was the strong

pride Canadians had in the kilt; perhaps it was the affection which our

people generally have had for the pipes; whatever the explanation, there

was a remarkable increase in the number of Scottish-named units when the

Canadian militia was reorganized after peace had been established in

1919. Not that new units were established, but a considerable number of

old infantry militia regiments were redesignated as Scottish units. In

this way the 20th Regiment (1866) became The Lome Rifles (Scottish) in

1931 and, after amalgamation with the Peel and Dufferin Regiment, The

Lorne Scots in 1936; the 21st (1885) became The Essex Scottish in 1927;

the 29th (1866) became The Highland Light Infantry in 1915; the 42nd

became The Lanark and Renfrew Scottish in 1927; the 43rd (1881) became

The Ottawa Highlanders in 1922 and, in 1933, The Cameron Highlanders of

Canada; the 50th (1913) and the 88th (1912) amalgamated

to become The Canadian Scottish in 1920; the 59th became The Stormont,

Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders in 1922; the 82nd became The Prince

Edward Island Highlanders in 1927; and the 103rd became The Calgary

Regiment and later The Calgary Highlanders in 1924. The Mississauga

Regiment lasted a year before becoming The Toronto Scottish in 1921. A

whole new array of kilted units (only The Lorne Scots were trewed) was

thus added to the Canadian Militia List.

But the new regiments, as well as the old, had their

problems in the between-wars years. These were not propitious years in

Canada for things military; indifference and hostility towards the

militia and towards military training were characteristic attitudes both

in Parliament and out. The 1920s were the years of pacifist idealism and

the 1930s of economic realism. Short of men, short of equipment, working

with hand-me-down uniforms and hand-me-down weapons, the officers and

men who devoted their time, effort and money to the militia performed a

service for their country which was ill-appreciated at the time.

Then everything changed. War broke out in 1939. Men

and money were readily available, and the military virtues, for nearly

20 years derided or ignored, became a source of popular admiration. On

this occasion the Defence Department did not repeat the blunder of

ignoring the militia units. The regiments mobilized in 1939 and 1940

were those which already existed in the peace establishment; and they

included a considerable number of Canadian Highland units. Among those

which served overseas in Italy and Northwest Europe between 1939 and

1945 were the 48th Highlanders (1st Canadian Infantry Brigade), The

Seaforth Highlanders of Canada (2nd Brigade), The Essex Scottish (4th

Brigade), The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, and The

Calgary Highlanders (5th Brigade), The Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders

(6th Brigade), The 1st Battalion Canadian Scottish (7th Brigade), The

Highland Light Infantry of Canada, The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry

Highlanders, The North Nova Scotia Highlanders (8th Brigade), The Argyll

and Sutherland Highlanders (10th Brigade), The Cape Breton Highlanders

and the Perth Regiment (11th Brigade), and The Lanark and Renfrew

Scottish (12th Brigade). The Toronto Scottish and the Queen's Own

Cameron Highlanders of Canada served as divisional troops in the 2nd and

3rd Canadian Infantry Divisions. The Lome Scots provided defence and

employment units at formation headquarters in Italy and Northwest

Europe. In the North American zone, we find The Renfrew Scottish, the

2nd Battalion Black Watch, the 2nd Battalion Canadian Scottish, The

Prince Edward Island Highlanders and The Scots Fusiliers.

The blooding of General Andrew McNaughton's Canadian

Army in World War II began in August, 1942,

when the Essex Scots returned with only two officers and forty-nine

other ranks from the blood-stained beach of Dieppe. In the following

year the 48th and the Seaforths of the 1st Canadian Division landed in

Sicily and, joined later by The Cape Breton Highlanders of the 5th

Armoured Division, began the long, slow, push up the boot of Italy,

through the Hitler and Gothic Lines almost to the gates of Bologna.

Finally, after twenty months of separation, they rejoined the other

Canadian divisions in Northwest Europe. In June, 1944, the 3rd Canadian

Infantry Division landed on the channel coast of France to be joined

subsequently in the Normandy bridgehead by the 2nd Infantry and 4th

Armoured Divisions. Under the command of General H.D.G. Crerar, they

broke through the German defences between Caen and Falaise, pursued the

retreating foe across France and Belgium into Western Holland, and

secured a winter position on the river Maas. The Scottish units in these

three Canadian divisions, like the other Canadian regiments, paid

heavily for their victories, but none perhaps so heavily as The Black

Watch, which experienced near disaster at the Verrieres Ridge on July

25, thus imposing upon the Calgary Highlanders the heavy and almost

intolerable burden of carrying out not only their own responsibilities

but those of The Black Watch, until the Royal Highlanders could recover.

That the Calgaries were able to do this speaks volumes for their grit,

training, and loyalty to their trust, and the determination of their

commanding officer, Donald MacLauchlan. Early in 1945, the final

offensive against the Germans began in the Reichwald. It continued, in

the face of determined and often suicidal opposition, until the crossing

of the Rhine. The final stage of the war saw the Canadians of both the

1st and 2nd Corps co-operating in the liberation of the whole of

Holland.

When we read the battle honours of the Scottish

regiments which formed part of the Canadian First Army, we read, in

effect, the battle honours of all Canadian overseas regiments - Moro

River, Ortona, Liri Valley, Hitler Line, Gothic Line, Coriano Ridge,

Savio Crossing, Caen, Bourguebus Ridge, the Scheldt, Walcheren, Breskens

Picket, Hochwald, Zutphen, Kusten Canal, Apeldoorn - these are only a

sampling of the names inscribed on the colours of the various units

which served in the Canadian army during World War II.

These and other names are today part of Canada's military

history, part of Canada's military tradition. It is a tradition which

has been purchased at a high price in torn bodies and mutilated minds,

and in determination, heroism, valour and self-sacrifice. It is a

tradition of which we can be proud.32

The immediate post-war period has witnessed the

organization of only two new Scottish regiments in Canada, or rather the

conversion of three infantry regiments into Scottish regiments, the Lake

Superiors, and the New Brunswick Rangers, which became respectively, the

Lake Superior Scottish and The New Brunswick Scottish, and The Perth

Regiment which became kilted in 1946. But other changes were in the

offing. Three Canadian Highland regiments, The Cape Breton, The Pictou

and The North Nova Scotia Highlanders were amalgamated into a single

regiment, The Nova Scotia Highlanders, with two battalions - in New

Brunswick, the New Brunswick Scottish and The Carleton and York became

the 1st Battalion of The Royal New Brunswick Regiment. Today some

eighteen Canadian regiments out of fifty-five in the post-war

Canadian Army List bear Scottish names.33 One of these, The Black Watch, was activated as a regular

regiment between 1953 and 1969. On the reduction to nil strength of the

regular battalions of The Black Watch, the militia battalion became once

again the perpetuating unit of what is the senior Highland regiment in

the Canadian armed forces.

V

Mairidh an cliu gu brath

May their names live forever

But there are clouds of doubt gathering on Canada's

military horizon. With the unification of the Canadian armed services

and the acceptance of the principle of uniformity, the question arises

as to what may be the future of Canada's Scottish regiments. To some

Canadians, these regiments appear as anachronisms, relics of a past that

is dead and gone. It is said that they no longer possess any ethnic

significance, since officers and men alike are drawn from all the

nationalities which now make up the composite Canadian population.

Others point out that active service had denationalized the Scottish

units in uniform as well as in personnel. They take the view that the

unsuitability of the kilt in modern warfare, apparent when the khaki

apron had to be introduced during the South African War and continued

during the War of 1914-18, became obvious even to the most stubborn Scot

when it had to be dropped entirely during World War II.

Modern combat uniform has no place for a tartan kilt or a

Glengarry bonnet. Efficiency must replace tradition, whether it be on

the field of battle or in the counting house.

Undoubtedly efficiency will have its way, if only

because it represents the future while tradition represents the past.

But if we ignore tradition, will we not lose those qualities which

tradition brings to us? Will we not sacrifice to the computer the

virtues which have been the strength of our military history? Can

efficiency provide an inspiration as moving and powerful as the memories

of the achievements of those who have gone before us? Does the skirl of

the pipes, the beat of the drum and the swing of the kilt no longer stir

the sluggish blood of the young Canadians, whether they be of Scottish

origin or not?

The end of the Scottish military tradition in Canada

will mean the end of an era that began centuries ago in the mountains

and glens of Scotland, that came to this country in the eighteenth

century in the haversacks of Fraser's and Montgomery's Highlanders, and

in the wooden trunks of those unhappy displaced Scotsmen seeking in

Canada the freedom and future their own land could not afford them after

"Butcher" Cumberland's "pacification."

NOTES

1. There is a further similarity between Canada and

Scotland. It is not always realized that Canada has only 3.9% of its

total area in arable land; 34.4% is in forest; 2.2% is in pasture; and

the remainder is in city, mountain, waste and water areas. This is in

contrast with the United States where 23.5% of the land is arable and

34.2% is pasture, with only 10% in city, mountain, waste and water

areas.

2. David Stewart of Garth, Sketches of the

Character, Manners and Present State of the Highlanders of Scotland

(Edinburgh: Constable, 1822) I, 218.

3. Lord Mahon, History of England from the Peace

of Utrecht to the Peace of Versailles

(London: Murray, 1853) iii, 324-327.

4. Quoted in John Prebble, Culloden (London:

Penguin, 1967), 163.

5. Ibid.,184.

6. Quoted in Mahon, iii,

327.

7. Gordon Donaldson, The Scots Overseas (London:

Hale, 1966), 32.

8. Quoted in Frank Adam and Sir Thomas Innes of

Learney, The Clans, Septs and Regiments of the Scottish Highlands

(Edinburgh and London: Johnson, 1952),p.440.

9. The colonel of The Black Watch was a Lowlander,

the Earl of Crawford and Lindsay, who had been raised in the Highlands

by the Duke of Argyll. For a list of the original officers of The Black

Watch see Stewart of Garth, I, pp. 227-228.

10. The Lieutenant-Colonel of the regiment was John

Campbell, later Duke of Argyll.

11. According to The Scots Magazine, 1973,

65,000 Scotsmen were enlisted, of which by far the greater number were

from the Highlands. See Adam and Learney, p.441.

12. See for instance A.G. Wauchope, A Short

History of The Black Watch Royal Highlanders 1715-1907 (London and

Edinburgh: Blackwood, 1908), and B. Fergusson The Black Watch and the

King's Enemies (London: Collins, 1950).

13. For James Johnstone's story see Memoirs of the

Chevalier Johnstone, trans. C. Winchester, (Aberdeen: 1871).

14. "Malcolm Fraser's Journal of the Operations

before Quebec, 1759," (Quebec Literary and Historical Society), 27.

Quoted in G.F.G. Stanley, New France: The Last Phase (Toronto:

McClelland and Stewart, 1969), p.243.

15. Stewart of Garth, I, 319. The battle of Culloden

was fought on April 16, 1746. The commander of the Highland host was

Lord George Murray.

16. C.W. Dunn, Highland Settler: A Portrait of the

Scottish Gael in Nova Scotia (Toronto: University of Toronto Press,

1953), p.64.

17. The sporrans were of raccoon rather than badger

heads, thus giving the unit a distinctive North American feature of

dress.

18. The Quebec Gazette, August 10, 1775. For

various documents relating to The Royal Highland Emigrants and the KRRNY

see A History of the Organization, Development and Services of the

Military and Naval Forces of Canada (Historical Section of the

General Staff, Ottawa, 1919-1920), Volumes II and III.

19. A History of the Organization etc.,

II, 167, 172: Caldwell to Murray, June

15,1776.

20. Ibid., ii, 143: Memorial of Malcolm

Fraser, March 31, 1791.

21. lbid.,iii, 103: Germain to Haldimand,

April 10, 1779.

22. John Keltie, A History of the Scottish

Highlands, Highland Clans and Highland Regiments (Edinburgh:

Fullarton, 1879) II, 566.

23. Quoted in J.P. MacLean, An Historical Account

of the Settlements of Scotch Highlanders in America prior to the peace

of 1783, together with Notices of the Highland Regiments and

Biographical Sketches (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co.,

1968), 318. Captain Alexander Macdonald's

letter book will be found in The Collections of the New York

Historical Society, 1882. For an account of the 2nd Battalion, R.H.E.,

together with the muster roll, see Jonas Howe, "The Royal Emigrants,"

Acadiensis (Saint John, N.B., 1904), pp.

50-75.

24. A History of the Organization etc.

II, 179: Carleton to Germain, July 8, 1776.

25. Ibid., iii, 162: Haldimand to Johnson,

July 13, 1780.

26. Ibid., iii, 109: Haldimand to Clinton, May

26, 1779.

27. Quoted in G.F.G. Stanley, "The Contribution of

the Canadian Militia during the War of 1812," in P.P. Mason, ed.,

After Tippecanoe - Some Aspects of

the War of 1812-15 (Toronto: Ryerson, 1963), p.31.

28. See L.H. Irving, Officers of the British

Forces in Canada during the War of 1812-15 (Welland: Tribune, 1908).

29. Quoted in R.M. Barnes (In collaboration with C.K.

Allen), The Uniforms and History of The Scottish Regiments 1625 to

the Present Day (London: Seely Service, 1956), p.316.

30. For the various changes in names and organization

of Canadian regiments, see C.E. Dornbusch, Lineages of the Canadian

Army, 1855-1961 (Cornwallville: Hope Farm Press, 1961).

31. H.M. Urquhart, The History of the 16th

Battalion (The Canadian Scottish) Canadian Expeditionary Force in the

Great War 1914-1919 (Toronto: Macmillan, 1932), p. 15.

32. Among the various regimental histories of

Canadian Scottish regiments are E.J. Chambers, The 5th Regiment Royal

Scots of Canada Highlanders (Montreal: Guertin, 1904); K. Beattie, 48th Highlanders of Canada 1891-1928 (Toronto, 1932); and

Dileas, History of the 48th Highlanders 1925-1956 (Toronto, 1957);

W. Boss, The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders 1783-1951

(Ottawa: Runge Press, 1952); F. Farran, The History of The Calgary

Highlanders 1921-1954 (Toronto, 1955); D.W. Grant, Carry On - A

History of The Toronto Scottish (n.p., 1949), H.M. Jackson, The

Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada (Montreal, 1953); R.

Roy, Ready for the Fray, The History of the Canadian Scottish

(Vancouver, 1958); C.B. Topp, The 42nd Battalion CEF (Montreal, 1931).

See The Regiments and Corps of the Canadian Army prepared by the Army

Historical Section, Volume I of the Canadian Army List (Ottawa, 1964).

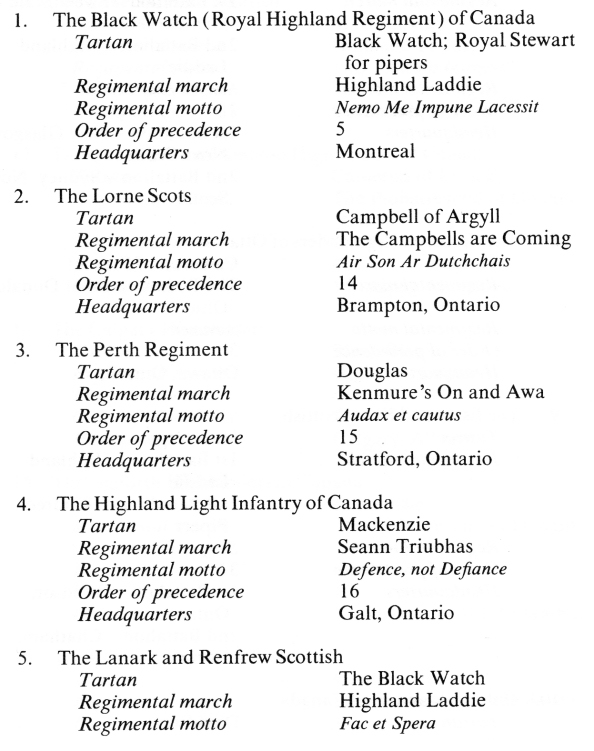

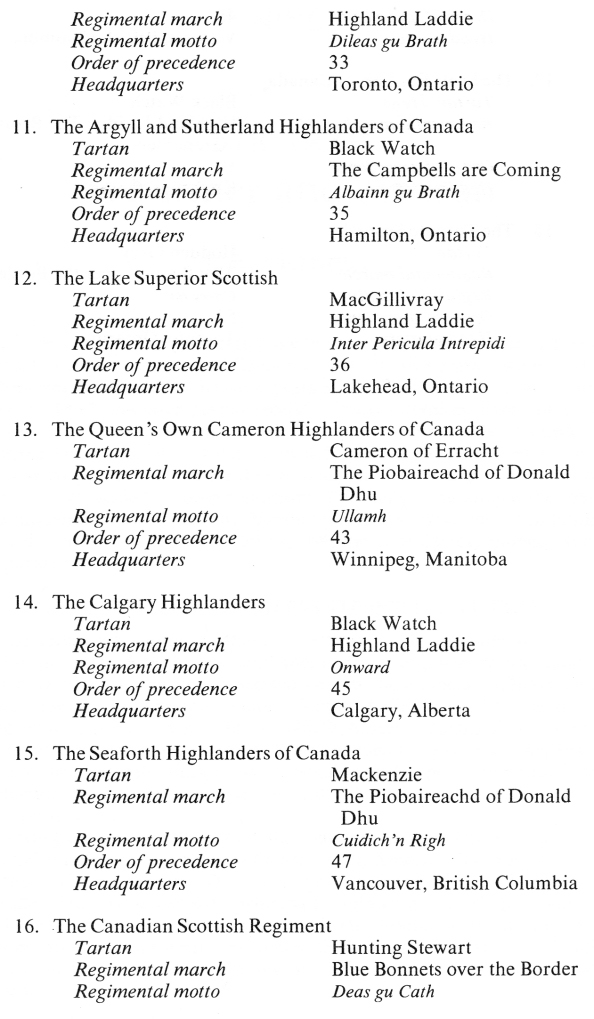

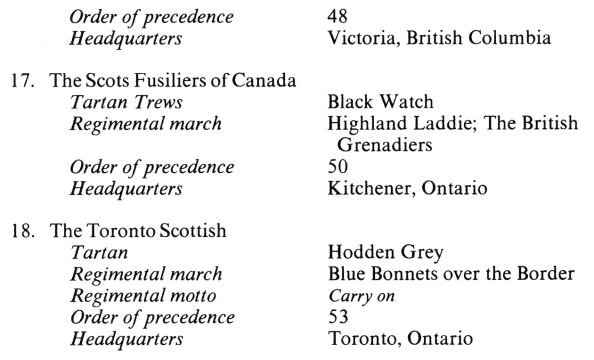

APPENDIX

Scottish Regiments in the current Canadian Army List