|

WHEN, in August, 1914, war burst suddenly

upon a peaceful world like distant thunder in a cloudless summer sky,

Canada, like the rest of the British Empire, was profoundly startled.

She had been a peace-loving, non-military nation, satisfied to develop

her great natural resources, and live in harmony with her neighbors;

taking little interest in European affairs, Canadians, in fact, were a

typical colonial people, with little knowledge even of the strength of

the ties that linked them to the British Empire.

Upon declaration of war by Great Britain Canada immediately, sprang to

arms. The love of country and empire which had been no obvious tiling

burst forth in a patriotic fervor as deep as it was spontaneous and

genuine. The call to action was answered with an enthusiasm the like of

which had rarely, if ever, been seen in any. British colony.

The Canadian Government called for 20,000 volunteers—-enough for a

single division—as Canada’s contribution to the British army. In less

than a month 40,000 men had volunteered, and the Minister of Militia was

compelled to stop the further enrolment of recruits. From the gold

fields of the Yukon, from the slopes of the Rockies on the west to the

surf-beaten shores of the Atlantic on the east; from workshop and mine;

from farm, office and forest, Canada’s sons trooped to the colors.

It will be the everlasting glory of the men of the first Canadian

contingent, that they needed no spur, either of victory or defeat: they

volunteered because they were quick to perceive that the existence of

their Empire was threatened by the action of the most formidable

nation-in-arms that the world had ever seen. They had been stirred by

the deepest emotion of a race—the love of country,

A site for a concentration camp was chosen at Valcartier, nestling among

the fine Laurentian hills, sixteen miles from Quebec, and convenient to

that point of embarkation. Within four days 6.000 men had arrived at

Valcartier; in another week there were 25.000 men. From centers all over

Canada troop trains, each carrying hundreds of embryo soldiers, sped

towards Valcartier and deposited their burdens on the miles of sidings

that had sprung up as though by magic.

The rapid evolution of that wild and wooded river valley into a model

military camp was a great tribute to the engineering skill and energy of

civilians who had never done the like before. One day an army of woodmen

were seen felling trees; the next day the stumps were tom out and the

hollows filled; on the third day long rows of tents in regular camp

formation covered the ground, and on the fourth day they were occupied

by civilian soldiers concentrated upon learning the rudiments of the art

and science of war.

Streets were laid out; miles of water pipes, sunk in machine-made

ditches, were connected to hundreds of taps and showier baths; electric

light was installed; three miles of rifle butts completed, and in two

weeks the camp was practically finished—the finest camp that the first

Canadians were destined to see. The building of Valcartier camp was

characteristic of the driving power, vision and genius of the Minister

of Militia, General Sir Sam Hughes.

Of the 33,000 men assembled at Valcartier, the great majority were

civilians without any previous training in warfare. About 7.000

Canadians had taken part in the South African war, fifteen years before,

and some of these, together with a few ex-regulars who had seen active

sendee, were formed into the Princess Patricia’s Light Infantry.

Otherwise, with the exception of the 3,000 regulars to be formed the

standing army of Canada, the men and most of the officers were amateurs.

It was therefore a feat that the Canadian people could well afford to be

proud of, that in the great crisis they were able, through their

aggressive Minister of Militia, not only to gather up these forces so

quickly but that they willingly and without delay converted their

industries to the manufacture of all necessary army equipment. Factories

all over the country immediately began turning out vast quantities of

khaki cloth, uniforms, boots, ammunition, harness, wagons, and the

thousand and one articles necessary for an army.

Before the end of September, 1914, the Canadian Expeditionary Force had

been roughly hewn into shape, battalions had been regrouped and

remodeled, officers transferred and re-transferred, intensive training

earned on, and all the necessary equipment assembled. On October 3,

1914, thirty-three Atlantic liners, carrying the contingent of 33,000

men, comprising infantry, artillery, cavalry, engineers, signalers,

medical corps, array service supply and ammunition columns, together

with horses, guns, ammunition, wagons, motor lorries and other

essentials, sailed from Gaspe basin on the Quebec seaboard to the

battle-field of Europe.

It was probably the largest convoy that had ever been gathered together.

This modern armada in three long lines, each line one and one-half miles

apart, led by cruisers and with battleships on the front, rear and

either flank, presented a thrilling spectacle. The voyage proved

uneventful, and on October 14th, the convoy steamed into Plymouth,

receiving an extraordinary ovation by the sober English people, who

seemed temporarily to have gone wild with enthusiasm. Back of that

demonstration was the conviction that blood had proved thicker than

water and that the apparently flimsy ties that bound the colonies to the

empire were bonds that were unbreakable. The German conviction that the

British colonies would fall away and the British Empire disintegrate

upon the outbreak of a great war had proved fallacious. It was,

moreover, a great demonstration of how the much-vaunted German navy had

already been swept from the seas and rendered impotent hy the might of

Britain’s fleet.

A few days later the Canadians had settled down on Salisbury Plain in

southern England for the further course of training necessary before

proceeding to France. There, for nearly four months in the cold and the

wet, In the fog and mud, in crowded, dripping tents and under constantly

dripping skies, they carried on and early gave evidence of their powers

of endurance and unquenchable spirit.

Lord Roberts made his last public appearance before this division and

addressing the men said in part: "Three months ago we found ourselves

involved in this war—a war not of our own seeking, but one winch those

who have studied Germany's literature and Germany’s aspirations, knew

was a war which we should inevitably have to deal with sooner or later.

The prompt resolve of Canada to give us such valuable assistance has

touched us deeply.

“We are fighting a nation which looks upon the British Empire as a

barrier to her development, and has in consequence, long contemplated

our overthrow and humiliation. To attain that end she has manufactured a

magnificent fighting machine, and is straining every nerve to gain

victory. . . It is only by the most determined efforts that we can

defeat her.”

And this superb German military organization, created by years of

tireless effort, was that which Canadian civilians had volunteered to

fight. Was it any wonder that some of the most able leaders doubted

whether men and officers, no matter how brave and intelligent, could

ever equal the inspired barbarians who, even at that very moment, were

battling with the finest British and French regulars and pressing them

steadily towards Paris.

In a short chapter of this kind attempting to deal with Canada’s effort

in the great war it is obviously impossible to go into detail or give

more than the briefest of historical pictures. Consequently much that is

fascinating can be given but a passing glance: for greater detail larger

works must be consulted. Nevertheless it is well to try and view in

perspective events as they occurred, in order to obtain some idea of

their relative importance.

In February, 1915, the first Canadian division crossed the Channel to

France, and began to obtain front-line experiences in a section of the

line just north of Neuve Chapelle.

While the first division had been going through its course of training

in England a second division had been raised in Canada and arrived in

England shortly after the first left it.

During that period the conflict in Europe had passed through eertain

preliminary phases—most of them fortunate for the Allies. The unexpected

holding up of the German armies by the Belgians had prevented the enemy

from gaining the channel ports of Calais and Boulogne in the first rush.

Later on the battle of the Marne had resulted in the rolling back of the

German waves until they had subsided on a line roughly drawn through

Dixmude, Ypres, Armentieres, La Bassee, Lens, and southward to the

French border and the trench phase of warfare had begun.

ON VIMY RIDGE, WHERE CANADA WON LAURELS

The Canadians took the important position

of Vimy Ridge on Easter Monday, April 9, 1917. They advanced with

brilliance, having taken the whole system of German front-line .trenches

hetween dawn and 6.30 a. m. This shows squads of machine gunners

operating from shell-craters in support of the infantry on the plateau

above the ridge.

Photo from Western Newspaper Union

GENERAL SIR ARTHUR CURRIE

Commander of the Canadian forces on the Western Front

The British held the section of front

between Ypres and La-B&ssee, ah out thirty miles in length, the Germans,

unfortunately, occupying all the higher grounds.

Shortly after the arrival of the Canadian division the British,

concentrating the largest number of guns that had hitherto heen gathered

together on the French front, made an attack on the Germans at Neuve

Cliapelle. This attack, only partially successful in gains of terrain,

served to teach both belligerents several lessons. It showed the British

the need for huge quantities of high explosives with which to blast away

wire and trenches and, that in an attack, rifle fire, no matter how

accurate, was no match for unlimited numbers of machine guns.

It showed the enemy what could be done with concentrated artillery

fire—a lesson that he availed himself of with deadly effect a few weeks

later.

Though Canadian artillery took part in that bombardment the infantry was

not engaged in the battle of Neuve Chapelle; it received its baptism of

fire, however, under excellent conditions, and after a month’s

experience iri trench warfare was taken out of the line for rest.

The division was at the time under the command of a British general and

the staff included several highly trained British staff officers.

Nevertheless the commands were practically all in the hands of

Canadians—lawyers, business men, real-estate agents, newspapermen and

other amateur soldiers, who, in civilian life as militiamen, had spent

more or less time in the study of the theory of warfare. This should

always be kept in mind in view of subsequent events, as well as the fact

that these amateur soldiers were faced hy armies whose officers and

men—professionals in the art and science of warfare—regarded themselves

as invincible.

In mid-April the Canadians took over a sector some five thousand yards

long in the Ypres salient. On the left they joined up with French

colonial troops, and on their right with the British. Thus there were

Canadian and French colonial troops side by side.

Toward the end of April the Germans reverted to supreme barbarism and

used poison gas. Undismayed, though suffering terrible losses, the

heroic Canadians fought the second battle of Ypres and held the line in

the face of the most terrific assaults.

When the news of the second battle of Ypres reached Canada her people

were profoundly stirred. The blight of war had at last fallen heavily,

destroying her first-born, but sorrow was mixed with pride and

exaltation that Canadian men had proved a match for the most

scientifically trained troops in Europe. As fighters Canadians had at

once leaped into front rank. British, Scotch and Irish blood, with

British traditions, had proved greater forces than the scientific

training and philosophic principles of the Huns. It was a glorious

illustration of the axiom “right is greater than might,” winch the

German had in his pride reversed to read “might is right.” It was

prophetic of what the final issue of a contest based on such divergent

principles was to be. So in those days Canadian men and women held their

heads higher and carried on their war work with increased determination,

stimulated by the knowledge that they were contending with an enemy more

remorseless and implacable than those terrible creatures which used to

come to them in their childish dreams. It was felt that, a nation which

could scientifically and in cold blood resort to poison gases— contrary

to all accepted agreements of civilized countries—to gain its object

must be fought with all the determination, resources and skill which it

was possible to employ.

Canada’s heart had been steeled. She was now in the war with her last

dollar and her last man if need be. She had begun to realize that

failure in Europe would simply transfer the struggle with the German

fighting hordes to our Atlantic provinces and the eastern American

states.

The famous Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry was originally

composed of soldiers who had actually seen service and were therefore

veterans. Incidentally they were older men and most of them were married

but the call of the Empire was insistent.

In the winter of 1914-15 the British line in Flanders was very thin and

the P. P. C. L. I’s. being a trained regiment was sent over to France

several weeks before the first Canadian division. It soon earned the

name of a regiment of extraordinarily hard-fighting qualities and was

all but wiped out before spring arrived. The immortal story of this

gallant unit must be read in detail if one wishes to obtain any clear

conception of their deeds of valor— of what it is possible for man to go

through and live. However, it was but one regiment whose exploits wore

later equaled by other Canadian regiments and it would therefore be

invidious to select any one for special praise. After operating as a

separate regiment for nearly two years and having been recruited from

the regular Canadian depots in England, it became in composition like

other Canadian regiments and was finally incorporated in the third

Canadian division.

In the spring of 1915, a Canadian cavalry brigade was formed in France

made up of Strathcona’s Horse, King Edward’s Horse, the Royal Canadian

Dragoons anti Canadian Mounted Rifles.

After the second battle of Ypres, the Canadians after resting and

re-organization, were moved to a section of the line near LaBassee. Here

they fought the battle of Festubert—a series of infantry attacks and

artillery bombardments, which gained little ground.

Shortly afterwards they fought the battle of Givenchy, equally futile,

as far as material results were concerned. Both of these battles had the

double object of feeling out the strength of the German line and of

obtaining the Aubers Ridge, should the attacks prove successful. In both

battles the Canadians showed great aptitude for attack, and tenacity in

their hold of captured trenches. They also learned the difficult lesson

that if an objective is passed by the infantry the latter enter the zone

of their own artillery fire and suffer accordingly.

In September, 1915, the Second Canadian Division arrived in Flanders and

took its place at the side of the First Canadian Division, then

occupying the Ploegsteert section in front of the Messines-Wytschaete

Ridge. The rest of the winter was spent more or less quietly by both

divisions in the usual trench warfare, and battling with mud, water and

weather.

It was here that the Canadians evolved the “trench raid,” a method of

cutting off a section of enemy trench, killing or taking prisoners all

the enemy inhabitants, destroying it and returning with little or no

loss to the attacking party. This method was quickly copied from one end

of the Franco-British line to the other; it proved a most valuable

method of gaining information, and served to keep the troops, during the

long cold winter months, stimulated and keen when otherwise life would

have proved most dull and uninteresting.

The Third Canadian Division was formed in January and February, 1916.

One infantry brigade was composed of regiments which, had been acting as

Canadian corps troops, including the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light

Infantry, and the Royal Canadian Regiment. The second infantry brigade

was made up of six Canadian mounted rifle regiments, which had comprised

part of the cavalry brigade. These two brigades, of the Third Division,

under the command of General Mercer of Toronto, almost immediately began

front-line work.

During this period, the Germans, making desperate efforts extending over

weeks of time, did their utmost to break through the French line at

Verdun and exhaust the French reserves. To offset these objects, a

fourth British army was assembled, which took over still more of the

French line, while a series of British attacks, intended to pin down the

German reserves all along the line, was inaugurated. One of these

developed into a fight for the craters—a terrible struggle at St. Eloi,

where, blasted from their muddy ditches, with rifles and machine guns

choked with mud and water; with communications lost and lack of

artillery support, the men of the Second Canadian Division fought gamely

from April 6th to April 20th, but were forced to yield the craters and

part of their front line system to the enemy.

Notwithstanding this the men of the Second Canadian Division at St. Eloi

fought quite as nobly as had their brothers of the First Division just a

year before, at the glorious battle of Ypres, a few miles farther north.

But it was a hitter experience. The lesson of failure is as necessary in

the education of a nation as that of success.

On June 2d and 3d, the Third Canadian Division, which then occupied part

of the line in the Ypres salient, including Hooge and Sanctuary Wood,

was smothered by an artillery bombardment unprecedented in length and

intensity. Trenches melted into irregular heaps of splintered wood,

broken sand bags and mangled bodies. Fighting gallantly the men of this

division fell in large numbers, where they stood. The best infantry in

the world is powerless against avalanches of shells projected from

greatly superior numbers of guns. The Canadian trenches were

obliterated, not captured.

By this time Britain had thoroughly learned her lesson, and now

countless shells and guns were pouring into France from Great Britain

where thousands of factories, new and old, toiled night and day, under

the inspiring energy of Mr. Lloyd George.

On June 13th, in a terrific counter-attack, the Canadians in turn

blasted the Huns from the trenches taken from them a few days before.

The First Canadian Division recaptured and consolidated all the ground

and trench systems that had been lost. Thus ended the second year of

Canadian military operations in the Ypres salient. Each of the three

Canadian divisions had been tried by fire in that terrible region, from

which, it was said, no man ever returned the same as he entered it.

Beneath its tom and rifted surface, thousands of Canadians lie, mute

testimony to the fact that love of liberty is still one of the most

powerful, yet most intangible, things that man is swayed by.

A very distinguished French general, speaking of the part that Canada

was playing in the war, said, “Nothing in the history of the world has

ever been known quite like it. My countrymen are fighting within fifty

miles of Paris, to push back and chastise a vile and leprous race, which

has violated the chastity of beautiful France, but the Australians at

the Dardanelles and the Canadians at Ypres, fought with supreme and

absolute devotion for what to many must have seemed simple abstractions,

and that nation which will support for an abstraction the horror of this

war of all wars will ever hold the highest place in the records of human

valor."

The Fourth Canadian Division reached the Ypres region in August, 1916,

just as the other three Canadian divisions were leaving for the Somme

battle-field farther south. For a while it occupied part of the line

near Kemmel, but soon followed the other divisions to the Somme, there

to complete the Canadian corps.

It may be stated here that though a fifth Canadian division was formed

and thoroughly trained in England, it never reached France. Canada,

until the passing of the Military Service Act on July 6,1917, depended

solely on voluntary enlistment. Up to that time Canada, with a

population of less than 9,000,000, had recruited 525,000 men by

voluntary methods. Of this number 356,9S6 had actually gone overseas.

Voluntary methods at last, however, failed to supply drafts in

sufficient numbers to keep up the strength of the depleted reserves in

England, and in consequence conscription was decided upon. By this

means, 56,000 men were drafted in Canada before the war ended. In the

meantime, through heavy fighting the demand for drafts became so

insistent that the Fifth Canadian Division in England had to be broken

up to reinforce the exhausted fighting divisions in France.

It would be an incomplete summary of Canada's part in the war that did

not mention some of the men who have been responsible for the success of

Canadian arms. It is obviously impossible to mention all of those

responsible; it is even harder to select a few. But looking backward one

sees two figures that stand forth from11 all the rest—General Sir Sam

Hughes in Canada, and General Sir Arthur Currie commander of the

Canadian corps.

To General Sir Sam Hughes must be given the credit of having foreseen

war with Germany and making such preparations as were possible in a

democracy like Canada. He it was of all others who galvanized Canada

into action; he it was whose enthusiasm and driving power were so

contagious that they affected not only his subordinates but the country

at large.

Sir Sam Hughes will be remembered for the building of Valcartier camp

and the dispatch of the first Canadian contingent. But he did things of

just as great importance. It was he who sought and obtained for Canada,

huge orders for munitions from Great Britain and thereby made it

possible for Canada to weather the financial depression, pay her own war

expenditures and emerge from the war in better financial shape than she

was when the war broke out. It was easy to build up a business once

established but the chief credit must go to the man who established it.

Sir Sam Hughes was also responsible for the selection of the officers

who went overseas with the first Canadian contingent. Among those

officers who subsequently became divisional commanders were General Sir

Arthur Currie, General Sir Richard Turner, General Sir David Watson,

Generals Lipsett, Mercer and Hughes.

Of these generals, Sir Arthur Currie through sheer ability ultimately

became commander of the Canadian corps. This big, quiet man, whose

consideration, prudence and brilliancy had won the absolute confidence

of Canadian officers and men alike, welded the Canadian corps into a

fighting force of incomparable effectiveness—a force which was set the

most difficult tasks and, as events proved, not in vain.

When Canada entered the war she had a permanent force of 3,000 men. When

hostilities ceased on November 11, 1918, Canada had sent overseas

418,980 soldiers. In addition to this about 15,000 men bad joined the

British Royal Air Service, several hundred physicians and veterinarians,

as well as 200 nurses, had been supplied to the British army, while many

hundreds of university men had received communications in the imperial

army and navy.

In September, October and November, 1916, the Canadian corps of four

divisions, which had been welded by General Byng and General Currie into

an exceedingly efficient fighting machine, took its part in the battle

of the Somme—a battle in which the British army assumed the heaviest

share of the fighting and casualties, and shifted the greatest burden of

the struggle from the shoulders of the French to their own. The British

army had grown vastly in power and efficiency and in growing had taken

over more and more of the line from the French.

The battle of the Somme was long and involved. The Franco-British forces

were everywhere victorious and by hard and continuous fighting forced

the Hun hack to the famous Hindenhurg line. It was in this battle that

the tanks, evolved by the British, were used for the first time, and

played a most important part in breaking down wire entanglements and

rounding up the machine gun nests. The part played in this battle by the

Canadian corps was conspicuous, and it especially distinguished itself

by the capture of Courcelette. Although the battles which the Canadian

corps took part in subsequently were almost invariably both successful

and important, they can be merely mentioned here. The Canadian corps now

known everywhere to consist of shock troops second to none on the

western front, was frequently used as the spearhead with which to pierce

particularly tough parts of the enemy defenses.

On April 9th to 13th, 1917, the Canadian corps, with some British

support, captured Vimy Ridge, a point which had hitherto proved

invulnerable. When a year later, the Germans, north and south, swept the

British line to one side in gigantic thrusts they were unable to disturb

this key point, Vimy Ridge, which served as an anchor to the sagging

fine. The Canadian corps was engaged at Arleux and Fresnoy in April and

May and was effective in the operations around Lens in June. Again on

August 15th, it was engaged at Hill 70 and fought with conspicuous

success in that toughest, most difficult, and most heart-breaking of all

battles - Passchendaele.

In 1918, the Canadian Cavalry Brigade won distinction in the German

offensive of March and April. On August 12, 1918, the Canadian corps was

engaged in the brilliantly successful battle of Amiens, which completely

upset the German offensive plan. On August 26th to 28th the Canadians

captured Monchy-le-Preux, and, in one of the hammer blows which Foch

rained on the German front, were given the most difficult piece of the

whole line to pierce—the Queant-Drocourt line. This section of the

famous Hindenburg line was considered by the enemy to be absolutely

impregnable, but was captured by the Canadians on September 3d and 4th.

With, this line outflanked a vast German retreat began, which ended on

November 11th with the signing of the armistice.

To the Canadians fell the honors of breaking through the first

Hindenburg line by the capture of Cambrai, on October 1st to 9th. They

also took Douai on October 19th, and Dena on October 20th. On October

26th to November 2d they had the signal honor of capturing Valenciennes

thereby being the first troops to break through the fourth and last

Hindenberg line.

It surely was a curious coincidence that Mons, from which the original

British army—the best trained, it is said, that has taken the field

since the time of Caesar—began its retreat in 1914, should have been the

town which Canadian civilians were destined to recapture. The war began

for the professional British army— the Contemptibles—when it began its

retreat from Mons in 1914; the war ended for the British army at the

very same town four years and three months later, when on the day the

armistice was signed the men from Canada re-entered it. Was it

coincidence, or was it fate?

During the war Canadian troops had sustained 211,000 casualties, 152,000

had been wounded and more than 50,000 had made the supreme sacrifice.

Put into different language this means that the number of Canadians

killed was just a little greater than the total number of infantrymen in

their corps of four divisions.

The extent of the work involved in the care of the wounded and sick of

the Canadians overseas may be gathered from the fact that Canada

equipped and sent across the Atlantic, 7 general hospitals, 10

stationary hospitals, 16 field ambulances, 3 sanitary sections, 4

casualty clearing stations and advanced and base depots of medical

stores: The personnel of these medical units consisted

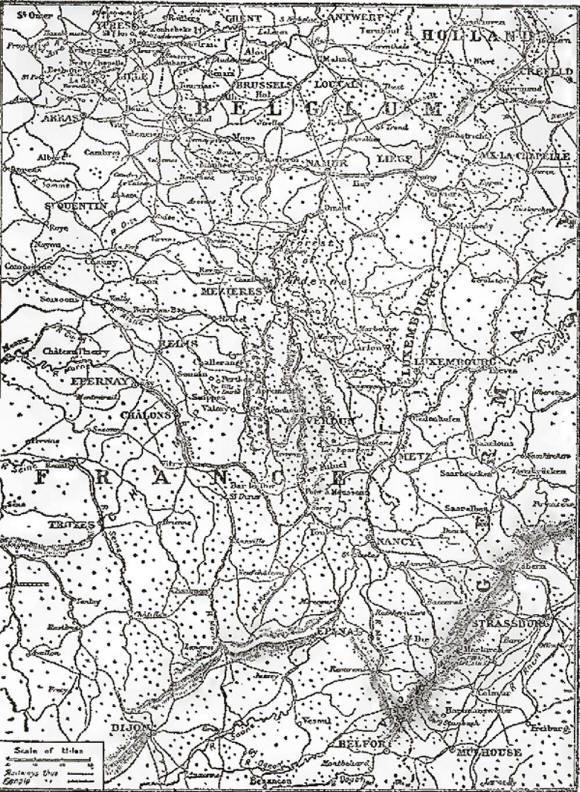

FROM THE VOSGES MOUNTAIN'S TO YPRES

Map showing the Northeastern frontiers of France, and neutral Belgium

through which the German armies poured in 1914. The battle line held

straight from Belfort to Verdun, with the exception of the St. Mihiel

salient, bove Verdun the line veered to the west, north of Rheims,

marking a wide line toward St. Quentin and Arras and bending back to

Ypres, held by the Canadians throughout the war.

of 1,612 officers, 1,994 nursing sisters

and 12,382 of other ranks, or a total of about 16,000. This will give

some conception of the importance of the task involved in the caring for

the sick and wounded of about 90,000 fighting troops, some 60,000

auxiliary troops behind the lines and the reserve depots in England.

The work of the Canadian Red Cross Society included the building and

equipping of auxiliary hospitals to those of the Canadian Army Medical

Corps; providing of extra and emergency stores of all kinds, recreation

huts, ambulances and lorries, drugs, serums and surgical equipment

calculated to make hospitals more efficient; the looking after the

comfort of patients in hospitals providing recreation and entertainment

to the wounded, and dispatching regularly to every Canadian prisoner

parcels of food, as well as clothes, books and other necessaries: The

Canadian Red Cross expended on goods for prisoners in 1917 nearly

$600,000.

In all the Canadian Red Cross distributed since the beginning of the war

to November 23, 1918, $7,631,100.

The approximate total of voluntary contributions from Canada for war

purposes was over $90,000,000.

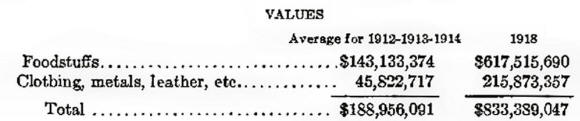

The following figures quoted from tables issued by the Department of

Public Information at Ottawa, show the exports in certain Canadian

commodities, having a direct bearing on the war for the last three

fiscal years before the war (1912-13-14), and for the last fiscal year

(191S); and illustrates the increase, during this period, in the value

of these articles exported:

As practically all of the increase of food

and other materials went to Great Britain, France and Italy, the extent

of Canada’s effort in upholding the allied cause is clearly evident and

was by no means a small one.

The trade of Canada for 1914 was one billion dollars; for the fiscal

year of 1917—IS it was two and one-half billion dollars.

Approximately 60,000,000 shells were made in Canada during the war.

Shortly after the outbreak of hostilities a shell committee was formed

in Canada to really act as an agent for the British war office in

placing contracts. The first shells were shipped in December, 1914, and

by the end of May, 1915, approximately 400 establishments were

manufacturing shells in Canada. By November, 1915, orders had been

placed by the Imperial Government to the value of $300,000,000, and an

Imperial Munitions Board, replacing the shell committee, was formed,

directly responsible to the Imperial Ministry of Munitions.

During the war period Canada purchased from her bank savings

$1,669,3S1,000 of Canadian war loans.

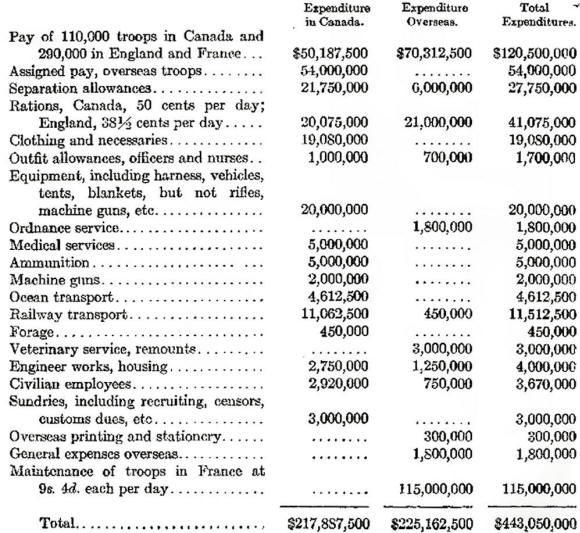

Estimates of expenditures for the fiscal year ending March 31, 1919,

demonstrated the thoroughness with which Canada went to war. They

follow:

Canada's Part in the Great War

2nd edition, July 1919 (pdf)

Electric Scotland Note:

The author of this account also published a report...

The Chemistry of Wheat Gluten

By Geo. G. Nasmith, B.A.

He also wrote the 2 volume...

Canada's Sons in the World War

A complete and authentic history of the commanding part played by Canada

and the British Empire in the World's Greatest War

Volume 1 |

Volume 2 |