|

Push on the York

Volunteers

THIS is not the attempt

to re-tell the battle of Queenston Heights, which has often been written

with enthusiasm, yea and even with eloquence and occasionally with

accuracy. It is merely to tell why as his last order Brock saw fit to

push on the York Volunteers.

Well on the morning of October 13th, 1812, a miniature British army was

defending a frontier of some thirty-six miles from Fort Erie to

Niagara-on-the-Lake, its commander, General Isaac Brock, being obliged

by his instructions from Sir George Prevost to adopt purely defensive

measures. In a letter of September 18th, Brock had written his brother

Savory: “You will hear of some decided action in the course of a

fortnight or in all probability we shall return to a state of

tranquility. I say decisive because if 1 should be beaten the province

is inevitably gone; and should I be victorious, I do not imagine the

gentry from the other side will care to return to the charge.”

He lay in some, force at Fort George, which he had equipped to silence

the American Fort Niagara, expecting that the movement of invasion would

be around his left flank, while Fort Niagara would effect a diversion

with its guns.

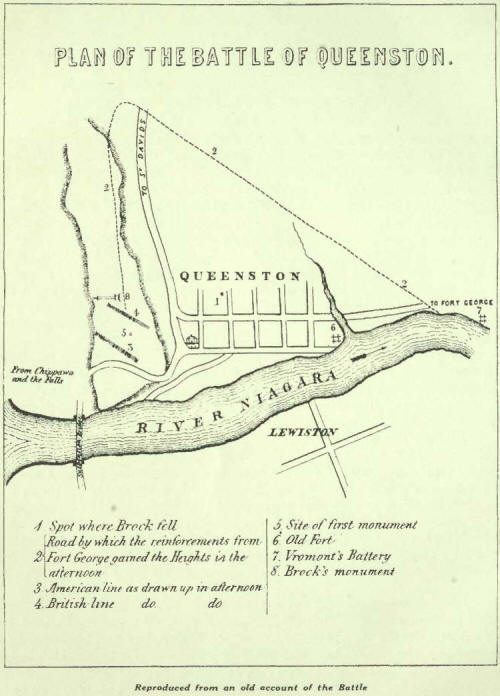

The seven miles of river from Fort George to Queenston he had picketed

with what history has dignified as batteries. Thus at the Heights about

half-way down the hill was the Redan Battery (armed with an eighteen

pounder) with Capt. Williams' flank company of the Green Tigers (the

49th Regiment). In the village of Queenston was the other flank company

under Major Dennis, along with Chisholm and Hatt's Militia Companies and

a brass six pounder and two three pounders handled by a small detachment

of artillery. Of the Yorks, Howard's Company, under Lieut. Robinson and

Cameron’s Company were stationed at Brown’s Point two miles below

Queenston. At night Robinson acted as an extra guard to the Battery at

Vroonian’s Point nearer Queenston and returned in the morning to the

command of his senior, Capt. Cameron, at Brown’s Point.

General Van Rensselaer did not attack Fort George, probably for the

reason that he felt he w«m expected there. But, merely demonstrating in

that quarter, he secretly concentrated at Fort Gray opposite Queenston

and proceeded to drive a wedge through the centre of the thinly held

line of British. Ilis boats were received on the Canadian shore with a

vigour that surprised them; some being sunk and those who landed getting

it hot and dry from musket and bayonet; the survivors being sent under

escort to Fort George. The guns in Fort Gray and the Redan on Queenston

kept up a furious cannonade that sent the news down the River to Cameron

and Brock.

Capt. Cameron was not a

professional soldier and was not instructed for this emergency. But with

a correct instinct he decided to march to the sound of the guns and put

his two companies of York Volunteers upon the road towards Queenston. On

their way a single horseman overtook and passed them at a gallop, waving

his hand to them and urging them as Robinson writes: “to follow with

expedition.” This was Isaac Brock on his way to his last battle. Soon

after, that darling of Canadian soldiery, Col. Macdonell galloped by,

also to meet his fate; and with him rode Capt. Glegg, Brock’s other

aide-de-camp.

It is a matter of history, fittingly commemorated by the tall monument

that towers above the heights he strove to regain,1 that Brock met his

end as he had won his victories by attempting the desperate to ward off

the seemingly inevitable. Nor was the attempt in vain; for the fury of

the contest and the boat loads of wounded returning to the American

shore had that moral effect on the adversary, Which decided the victory

of the afternoon.

Twice Brock strove to gain the heights with every soldier he could spare

from Queenston and twice he failed. But the words, “Push on the York

Volunteers,” whether spoken by him just before or after he was struck

were not heroics nor melodrama but a plain military order to throw into

the issue his one available reserve, namely, the two companies under

Capt. Cameron which following the trail of their general were panting up

the road to Queenston.

Col. Macdonell rode to his death on the left flank of the York

Volunteers and when he fell mortally wounded Capt. Cameron carried him

off amid a shower of musketry. The shattered remains of these much tried

pickets were rallied about a mile below the heights and marching through

the fields back of Queenston joined themselves to the centre of

Sheaffe’s advancing column. Nor did the gruelling punishment of the

morning prevent their earning their place in that famous dispatch of

General Sheaffe, in which he says:

“Lieut-Cols. Butler and Clark of the militia; and Capts. Hatt, Durand,

Howe, Applegarth, James Crooks, Cooper, Robert Hamilton, McEwen, Duncan

Cameron, and Lieuts. Richardsons and Thomas Butler, commanding flank

companies of the Lincoln and York militia led their men into action with

great spirit.''

The great spirit with which that day they led on their men and General

Sheaffe led his, was that of Isaac Brock. e shall see that this spirit

evaporated from some of the generals if not from their juniors, and that

soldiers who under Brock’s influence were intrepid, like Sheaffe and

Proctor, became soon afterwards vacillating, disheartened and timorous.

|