|

Stepping out in 1885

THE Second Rebellion of

Louis Riel is a sermon on the words “Watch therefore, for ye know

neither the day nor the hour,” and illustrates the frightful rapidity

with which peace ends and war begins. In an opposition paper {The Globe)

of March 20th, appeared this small item:—

“Prince Albert, March 19th. Louis Riel, the hero of the ‘Red River

Rebellion,’ recently exiled from Manitoba, has created dissension among

the half-breeds and an outbreak is imminent. The situation is considered

critical.’’

The administration of the day went placidly on attending to other

matters and seeking to keep the public of eastern Canada from troubling

about the North West. Some of the government press rebuked the Globe,

others ignored it. The Canadian public was more interested in

Afghanistan than Saskatchewan.

Suddenly on Saturday, March 28th, the government organ itself The

Mail—-sounded the alarm and proclaimed a call to arms giving the

narrative of the defeat of Crozier, and saying in its editorial: “Up to

last evening the government had reasonable grounds for believing that

the disturbances fomented by Louis Riel in the Saskatchewan region were

of a comparatively insignificant character. That view must now be

abandoned."

On the morning of the same day eighty men of the infantry at the

barracks known as “C School," and two hundred and fifty each of the

Queen’s Own and Royal Grenadiers were called out, and at 10 a.m. on

Monday 30th marched out from the armoury and entrained for the North

West. General Middleton had already started for Qu’Appelle with the 90th

Battalion, the W nnipeg Battens mid some cavalry.

The militia authorities of that time seemed of a mind not to do too much

in one day and kept calling out the battalions picce-mcal instead of

mobilizing a strong force and at once forwarding it to General

Middleton. That the men he had to hand in the combats at Fish Creek and

Batoche proved sufficient for the work was part of the good fortune of

that rugged old fighter. But there was no margin of safety and not even

complete success can justify the principle of campaigning by driblets.

The turn of the 12th came on March 30th, when Col. Denison, the D.A.G.,

having just got word from Ottawa, issued an after dinner order at 8

p.m., calling out four companies of the Rangers along with four of the

Simcoe Foresters. The machinery for selecting this force is embodied in

a regimental order which we give in full:—

Toronto, March 30th. J88S.

Regimental orders by Lieut.-Col Wyndham, commanding 12th Battalion.

No 1. Four companies of the battalion being ordered for active service

the officers commanding companies will at once-assemble their companies

at then-respective company headquarters for inspection.

No. 2. Each company will furnish twenty men and one Sergeant. Companies

1, 3, 5 and 7 will furnish two Sergeants: the men must be inspected by

the Surgeon or Assistant Surgeon and the Adjutant.

No. 3. Surgeon Hillary will be in attendance at the headquarters of the

Newmarket Company, on the 31st, for the purpose of inspecting the men

belonging to the Newmarket and Sharon Companies, between the hours of 9

and 12, and at the headquarters of the Aurora Company, between the hours

of one land four.

No. 4. Assistant Surgeon Machell will inspect the Riverside, Parkdale,

Yorkville and Seaton Village Companies, during the evening of the 31st,

at their respective, company headquarters.

No. 5. The Adjutant will attend at Newmarket, Aurora, Parkdale, Seaton

Village, Yorkville and Riverside on the;£ame day, and at the same time

as the Surgeon and Assistant Surgeon for the purpose of selecting

suitable men.

No. 6. The 12th Battalion will furnish Quarter-Master Sergeant, and

Paymaster's Clerk.

No. 7. The following officers are detailed for active service in the

North West.

Major Wayling, in command of Newmarket and Sharon.

Capt. Smith, in command of Aurora and Sutton.

Capt. Brooke, in command of Yorkville and Seaton Village.

Capt. Thompson, in command of Parkdale and Riverside.

Lieut. J. K. Leslie, of No. 3 Company.

Lieut. C. Venn elf, of No. 5 Company.

Lieut. J. T. Symons, of No. 5 Company.

Lieut. T. W Booth, of No. 5 Company.

Lieut. Fleury, of No. 7 Company.

Lieut. J. A. W. Allan, of No. 8 Company.

Lieut. Geo. Sutherland, of No. 7 Company.

Quarter-master Smith.

By order

John T. Thompson, Captain and Adjutant.

So much for the formal order. The real message was by bugle. A copy from

a contemporary paper.

Rousing the Rangers

A Midnight Assembly on

the Bugle Call.

The Call Responded to Promptly.

“The resonant tones of

a bugle sounding the assembly on Monday night, roused many a slumbering

citizen in the northern, western, and eastern parts of the city, between

midnight and dawn and large numbers of those acquainted with the meaning

of the call and who belonged to military organizations, hastily dressed

themselves and rushed out under the impression that was intended to

summon the remaining portions of the Queen’s Own and Grenadiers together

for sendee. Such, however, was not the case, the summons being intended

only for members of the 12th Battalion of York Rangers, companies of

which regiment have their headquarters in Parkdale, St. Paul’s Ward,

Seaton Village and Riverside. Col. Wyndham, who commands the Rangers

received orders to draft four companies out of his command to form one

wing of a battalion for active service, the other half of which will be

drawn from the 35th or Simcoe Foresters.”

As an example of how

the Rangers responded to the call we give the follow pen sketch:—

“The Parkdale Platoon assembled at the company armoury, at eight o’clock

yesterday morning and having been provided with their outfit fell into

line and were addressed by Lieut. Booth, who thanked them for their

prompt response to the call of duty. No. 1, or the Parkdale Company have

a brass band and headed by it matched out through the village and

afterwards returning to the armoury were dismissed for the day.”

The companies being paraded and the selections or rather rejections

being made, for all were pressing to go, the understanding was that the

companies were to be drilled daily at their headquarters until Saturday,

April 4th. On this date it was expected the whole York-Simcoe Battalion

would be assembled at the New Fort and dressed up and down prior to its

departure for the scene of war.

Here, however, this bi-county contingent received one of those spasmodic

impulses to the front that characterized the campaign. On Thursday,

April 2nd, the newly provisional battalion found itself aboard of two

trains bound for the North West. This new order caught the men before

they had time to affect that trimness of appearance which in the eyes of

many is the essence of soldierliness. An eyewitness reported, “It is

much to be feared that the departure of this battalion has been much too

hurried. Of the Toronto contingent at least it may be positively said

that they were not in a fit state to take the field. The clothing in

many instances is old and rotten, the knapsacks ill fitted and so badly

packed that a day’s march in them would be sufficient to break down a

Hercules. We shall see that nevertheless the regiment could march and

did.

Now if it had been designed to specially inure troops to the extremes of

comfort and hardship and accustom them to sudden transitions from the

easiest to the hardest modes of travel, a more appropriate route and

season could not have been selected than the then line of the Canadian

Pacific RaihvaA7, in the early days of April. The railway itself the men

found comfortable and its officials considerate and energetic. But the

section north of Lake Superior, one of the bleakest regions in the

world, had formidable gaps where the railway ceased—the “End of Iron”

they called it in those days.

The surmounting of these gaps by the first regiment to be sent,—the

Queen’s Own Rifles,—was the subject of much highly strained writing on

the part of certain correspondents who appeared to prefer a picturesque

luridosity of style to the reputation of their regiment for manliness

and endurance. The tender-souled public of Toronto were tortured with

pictures of the most frightful weather conditions and by representations

of their sons, frostbitten, sun-blistered, snow-blind and delirious. In

reality the Queen's Own Rifles and the next comers, the 10th, stood

their marches and as the saying is “stuck it out.”

The effect of all this “scare writing” on the men of the York-Simcoe

Battalion was that they made up their minds that, when they came to the

gaps that had to be marched, they would crush through in quicker time

than their predecessors, and they did.

The first gap, which began at Dog Lake, was crossed with sleighs

carrying twelve men apiece. At the end of this ride our contingent found

no train waiting and took their first experience of a bivouac. One of

them writes: “We had to lie out on a cold night without tents or any

cohering except a blanket on eighteen inches or two feet of snow and

recommence our journey next morning without breakfast on open

construction cars.” Another more fortunate got “a little bread and

coffee.”

Then came luxury and as the ancient histories would say, “the delights

of Capua”. They got a good supper at Fort Monroe. One who was billetted

with Mr. Samuel Allison slept (for the first time after leaving Toronto)

with some seventy others on the bare boards "with the whole of that

number in a room about 12 feet by 16 feet.”

Having thus reposed in close order, the troops were next day permitted

to extend themselves in a series of marches alternated with rides on

sleighs and flat cars. One of the 12th fortunately wrote down to his

“chum” in Toronto, while the impressions were fresh. We quote his words;

“On the morning of the 7th we had breakfast and proceeded to march on

the Lake (Superior) from Fort Munro to MacKellar’s Harbour distant 25

miles. It rained all the time and we were up to our ankles in ice water,

but in spite of the strong wind which also prevailed not a man fell out

and we made the distance seven and a half hours. I can assure you I felt

very tired and cold, being drenched through. Here we had to cut wood and

build fires in the open air and each man was served with a biscuit.

“We remained for about six hours trying to dry our clothes, but it

stopped raining and commenced to freeze and while one’s back was

freezing he would be burning in front. We left by flat cars about twelve

o’clock to go fifteen miles further to Jackfish Bay. Had supper about

two a.m., hard tack and pork.”

Treading on the heels of the 65th

“At Jackfish Bay we overtook the 65th, a Montreal Regiment, and as a

consequence had a day to dry up and recruit ourselves.” This

deliberation of the 65th caused some controversy as to whether that

regiment “had balked at the gaps.” Whether that fine regiment was not a

little influenced by racial reluctance to take part against the Metis,

is one of the historic questions of the campaign that are not now worth

solving. That the 65th could march and endure was abundantly proved

later on.

Having crossed the third gap partly on foot and partly with the sleighs

that had returned from conveying the 65th, the York-Simcoes were huddled

together on flat cars and rode some sixty-five dismal miles to Nipegon,

Where they arrived at 10 p.m. of April 9th, to commence the march across

the last, the shortest and the weariest of the gaps. The exquisite

nature of the fatigue incurred was carefully set down bv one who seems

to have ached with the very recollection. he says:

“And this though the shortest was the most trying march of the whole. We

started about ten o’clock at night and in the dark tramped about fifteen

miles over the lake on the ice. You may realize what these marches on

the ice mean when I tell you that there was from twelve to eighteen

inches of snow covering it and the track we had to walk in was simply

gutters made by the runners of the transport sleighs. In daylight when

you could see to place your feet there was a tendency in them to slide

together all the time from the sloping sides of the gutter and at night

this tendency was increased ten fold. To add to the discomfort the track

in the first and last marches was partly filled with water from the

melted snow. In the first march during the prevailing rain it was from

six to eight inches deep.”

The appearance of the regiment after it came through and arrived at

Winnipeg on the morning of April 11th, was noted in the Winnipeg Times:

“The experiences of the men have been similar to the other troops who

came by the Lake Superior division, but despite the discomforts

attendant upon the several fatiguing marches the battalion impresses one

very creditably. The men are a robust class and their demeanour and

deportment are irreproachable. They have been on the road nine days,

having left Toronto a week ago Thursday last. At Jackfish Bay, they

overtook the 65th Battalion, but were delayed there by the limited

transport accommodation. The weather for many days was wet and cold, and

the roads almost impassable. Although sinking deep in the mud, one march

of twenty-six miles was made in eight hours, and not one of the men

faltered, a record which the battalion points to with pride. No sickness

or accidents of any kind occurred, and the entire body are in splendid

spirits. Upon arrival here the men were furnished breakfast at the C.P.R.

dining hall. In the battalion are a number of the old Mounted Police

Force, who are to form a detachment for service as scouts. The

battalion, in accordance with orders from Ottawa, are to go into

barracks here for several days, and at noon orders were issued for them

to go into camp on the west side of Main Street, just beyond the railway

track.”

Any expectation that

was forming in the men’s minds of being allowed to relax themselves in

Winnipeg was rudely dispelled by the battalion being entrained <m the

night of Sunday the 12th, and carried westerly over three hundred miles

to Qu’Appellls Station or Troy, where they arrived on Tuesday the 14th.

Here the 12th pitched camp and remained until Friday the 17th, when they

were marched to Fort Qu’Appelle, a distance of some eighteen miles,

through the mud.

This march, mud and all, seemed so light compared to the gaps that the

boys found food for merriment in many trifling episodes on the way. For

example, Private Theobald in the military phrase “Look on scarlet,” or

in other words left off his overcoat. It is a rule among the military

that this should be done on a set day by order formally issued. This

unauthorized action of Private, Theobald making himself conspicuous by

his red coat among all the dark overcoats, incensed one of the transport

oxen, “and it caught Private Theobald in the bosom of his pants with its

horns and landed him in a pond of water yelling at the top of his

voice". On April 21st, the 35th rejoined the 12th at Fort Qu’Appelle,

“and the 12th gave them a hearty cheer and one of the boys had a fiddle

and came in playing it at the head of the battalion. The York Rangers

pitched their tents for them.” From this time until the 13th day of May,

“the Direction'' kept the York-Simcoes eating their hearts out at Fort

Qu’Appelle.

During this enforced stay at Fort Qu’Appelle the officers were not idle

and provided a sufficiency of drill and tactical work for those under

their command. Sergt. Bert Smith of the 12th, in a letter written April

27th, gives an idea of what was going on. “We have had the Toronto Body

Guards also the Winnipeg and Quebec Body Guards with us for four or five

days, but most of them have gone on to the front. About 3 a.m. Saturday

last, I heard Capt. Thompson trying to wake me up. When I got awake he

said he wanted four of the best men in my tent to go on a march that we

thought had been postponed. We sent ninety good men and twenty cavalry,

but the boys were back since Sunday noon, for they failed to capture

anything. It was some of Riel’s supplies they were after. Everything is

quiet around here.”

On May 6th the camp had an experience which is a necessary part of

military training. We may give it in the words of Capt. Campbell, of the

Simcoe Foresters.

“Last night (Wednesday) our camp had a genuine rouse. We had a picket

posted at a ford down the river about 800 yards from the camp, there

being a sergeant’s guard at the place. About 11 o’clock the sentry

thought he saw four men with some horses at a little distance from him.

He gave the challenge, but there was no answer and the parties attempted

apparently to get under cover. The sentry at once fired and called out

the guard. This of course was heard in camp and immediately the bugle

sounded the Assembly and then there was a rushing to arms and mounting

in hot haste. In about two minutes every available man in the regiment

was under arms and ready to fight. The companies were rapidly placed in

fighting order round our camp, some being sent out to assist the picket

and others to defend the bridge."

“This was all done without noise or confusion. After the first shot some

of the other pickets and sentries answered and for a short time the

firing was pretty lively and everything had the sound and appearance of

a genuine attack.”

On May 18th, acting under urgent orders, Lieut.-Colonel O’Brien set his

battalion to a forced march to Humboldt.

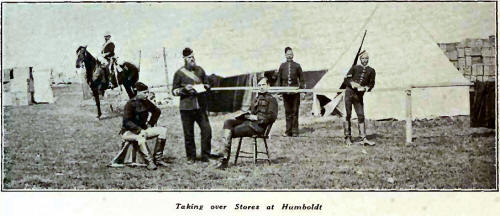

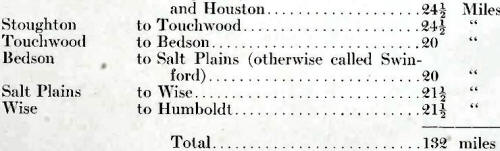

The distances given in the line of march for troops as arranged by Capt.

Bedson in charge of the transport were as follows:

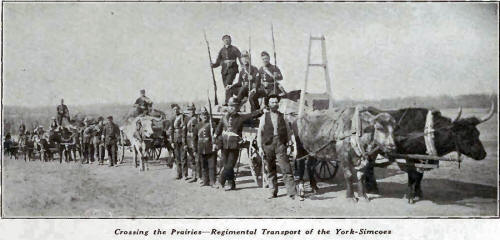

This distance the York-Simcoes

devoured in seven days. When we figure that this makes practically an

average daily march of 19 miles and compare it with the normal 13½ miles

of European infantry it is borne in on us that these volunteers were in

haste to get to the front.

The first day’s march is described in the diary of a Simcoe Forester:

"May 13th, we left Fort Qu’Appelle at six a.m. under command of Col.

O’Brien, M.P. On climbing the hill at Fort York, we halted and the

troops were photographed. We marched about 18 miles when we halted for

dinner, and took up a company that was stationed here under command of

Major Wayling. Here was erected a very nice fort which we christened

Fort Wayling. We arrived at Howden, at seven p.m., distant from

Qu’Appelle about 28 miles.”

This strenuous stepping out was also a test of discipline and enabled

the battalion to rid itself of one or two weak characters with a taste

for malingering. On the second day, one Private Fontaine incurred

courtmartial by a difference with Col. O’Brien, as to the magnitude and

importance of the blisters on Fontaine’s legs. The colonel was a tall

grim man who might have sat for a portrait of one of Wellington’s

generals. He could and generally did walk all day; and inaccessible to

fatigue himself wasted no pity on others and was the very man to make a

young battalion kick the miles out behind it. In addition he was a

fluent and convincing public speaker with great powers of expression.

The diarist records that “he spoke to the officers in a very harsh

manner while on the march.” His manner to the privates may, therefore,

have appeared to lack sympathy. When Fontaine appealed to the colonel to

allow him to ride he said that if Fontaine asked him again he would flog

him. The upshot was that Fontaine was sentenced for insubordination and

deserted during the night along with another malingering rascal.

Next morning Col. O'Brien addressed the whole battalion on the subject

of desertion and his listeners vouch that if his words were not exactly

a privilege to hear they were at least not difficult to remember.

Twice during the seven days the battalion was overtaken by terrific

thunder storms accompanied by hail-stones of a size unknown in Ontario.

As their great coats and oil sheets were on the wagons behind, the men

were soaked to the skin, but seem to have taken no hurt. On the

19th-they made Humboldt, and met an escort of the Body Guard with White

Cap and his band of prisoners, Mrs. White Cap riding astride of Lieut.

Fleming’s horse.

The appearance of the battalion when it struck Humboldt was described by

a newspaper correspondent.

“The 35th and 12th have just reached camp, Col. O’Brien in command. They

marched- actually marched—from Fort Qu’Appelle, doing the 127 miles

since Wednesday morning last,—seven days in all. The men came in as

lively as crickets and are now resting half a mile along the trail south

of the Body Guard. Col. Tyrwhitt, senior Major in command, marched the

entire distance permitting his servant to ride his horse.”

Among the members of

the 12th, there was none on (and more often off) the strength who saw

more than Staff-Sergt. Brown. Originally picked to go with the

contingent he was deemed medically unfit and on his way to the station

was ordered by Capt. Thompson to fall to the rear. He obeyed, but

smuggled aboard the train and after various vicissitudes and making

himself useful in various capacities he reached Winnipeg. Here he got

himself attached to the Brigade Staff, from April 13th to the 30th, when

he rejoined the battalion at Fort Qu’Appelle, Here for a time his

presence was ignored, but on May 11th, he was made sergeant of a guard

of twelve men, one corporal and one mounted soldier. This guard was kept

on duty for forty-eight hours without relief and then without sleep

compelled to undergo the march that began on May 13th, with the result

that three men of the guard collapsed. On May 20th, Brown was again

taken off the strength and attached to the Supply Officer in Humboldt, a

quaint inebriate familiarly known as “Micky Free". In this capacity he

remained at Humboldt, enjoying the festivities that celebrated the

Queen’s birthday, and making the highest score in the battalion rifle

match, until hearing on June 30th that a telegram had arrived to hold

the troops in readiness for home he applied for leave of absence. Under

leave, Brown proceeded as far as Regina, where by the favor of an

acquaintance in the North West Mounted Police, he was permitted to see

Louis Riel marching up and down taking exercise in the jail paddock and

carrying a ball and chain in his arms. His picture of Riel, jotted down

at the time is not that of the shifty and loquacious demagogue he was

sometimes painted:

“Riel is a big burly fellow and stands about five feet ten inches high;

very broad shouldered; 190 pounds; dark complexion, black long hair and

beard; high cheek bones and very large nose. With a down and sullen

look; very polite to guards, and looked like a farm labourer returning

from work without a coat on.”

Having accomplished what no other of the 12th for all their marching

succeeded in doing, namely, having a look at the Rebel Leader, Brown got

back to Qu’Appelle in time to see the York-Simcoes march in, which they

did, having adhered throughout the distance from Humboldt to Qu’Appelle

to the Body Guard and earned from Col. Derision the name of his “Foot

Cavalry.”

The journey home of the regiments from the North West was a series of

receptions. At Port Arthur the troops embarked for Collingwood and

entrained for Toronto. At Barrie the good feeling that prevailed between

the 35th and the 12th was evidenced by the presentation of a sword and

belts to Lieut.-Col. Trywhltt of the 35th, on behalf of the 12th

officers. The celebrations held in Toronto on July 22nd and 23rd will

long be remembered and the York-Simcoe Battalion received its official

order to “Dismiss ” on July 24th, 1885. It had not got into action; like

Wellington’s Sixth Division which was nicknamed “the Marching Division,”

because of its continuous marching up and down without the fortune of a

battle. But for the Sixth Division, there came at last the opportunity

of Salamanca, and who knows what the future holds.

|