|

A glance at a physical

map of the country will serve to show the relative position of the main

bodies of the North American forest, the division of the woods where the

wedge-shaped north-western corner of the plains comes in, and their

well-defined limit on the edge of the barren grounds, coincident with

the line of perpetual ground frost.

Characterised by a

predominance of coniferous trees, the great belt of forest country which

constitutes the hunting grounds of the Hudson’3 Bay Company, has its

nearest approach to the Arctic Ocean in the Mackenzie Valley, becoming

ever more and more stunted and monotonous until it merges at length into

the barren waste.

In its southern

extension, on meeting the northern extremity of the prairies, it

branches into two streams— the one directed along the Pacific coast line

and its great mountain chain; the other crossing the continent

diagonally between the boundaries of the plains and Hudson’s Bay towards

the Atlantic. On this course the forest soon receives important

accessions of new forms of trees, gradually introduced on approaching

the lake district, and loses much of its Sterner character.

The oak, beech, and

maple groves of the Canadas are equally characteristic of the forest

scenery of these regions, with the white pine or the hemlock spruce.

On approaching the

Atlantic seaboard, the forest is again somewhat impoverished by the

absence of those forms which seem to require an inland climate. In the

forests of Acadie many Canadian trees found farther westward in the same

latitude are wanting, or of so rare occurrence as to exercise no

influence on the general features of the country, such as the hickory

and the butternut. “In Nova Scotia,” says Professor Lawson, “the

preponderance of northern species is much greater than in corresponding

latitudes in Canada, and many of our common plants are in Western Canada

either entirely northern, or strictly confined to the great swamps,

whose cool waters and dense shade form a shelter for northern species.”

Though certain soils

and physical conformations of the country occasionally favour exclusive

growths of either, the woods of the Lower Provinces display a pleasing

mixture of what are locally termed hard and soft wood trees—in other

words, of deciduous and evergreen vegetation. Broken only by clearings

and settlements in the lines of alluvial valleys, roads, or important

fishing or mining stations, the forest still obtains over large sections

of the country, notwithstanding continued and often wanton mutilation by

the axe, and the immense area annually devastated by fire. The fierce

energy of American vegetation, if allowed, quickly fills up gaps, and

the burnt, blackened waste is soon re-clothed with the verdure of dense

copses of birch and aspen.

The true character of

the American forest is not to be studied from the road-side or along the

edges of the cleared lands. To read its mysteries aright, we must plunge

into its depths and live under its shelter through all the phases of the

seasons, leaving far behind the sound of the settlers axe and the

tinkling of his cattle-bells. The strange feelings of pleasure attached

to a life in the majestic solitudes of the pine forests of North America

cannot be attained by a merely marginal acquaintance.

On entering the woods,

the first feature which naturally strikes us is the continual occurrence

of dense copses of young trees, where a partial clearing has afforded a

chance to the profusely sown germs to spring up and perpetuate the

ascendancy of vegetation, though of course, in the struggle for

existence, but few of these would live to assert themselves as forest

trees. As we advance we perceive a taller and straighter growth, and

observe that many species, which in more civilised districts are mere

ornamental shrubs, throwing out their feathery branches close to the

ground, now assume the character of forest trees with clean straight

stems, though somewhat slender withal, engendering the belief that, left

by themselves in the Spen, they would offer but a short resistance to

wintry gales. The foliage predominates at the tree top; the stems

(especially of the spruces) throw out a profusion of spikes and dead

branchlets from the base upwards. Unhealthy situations, such as cold

swamps, are marked by the utmost confusion. Everywhere, and at every

variety of angle, trees lean and creak against their comrades, drawing a

few more years of existence through their support. The foot is being

perpetually lifted to stride over dead stems, sometimes so intricately

interwoven that the traveller becomes fairly pounded for the nonce.

This tangled

appearance, however, is an attribute of the spruce woods ; there is a

much more orderly arrangement under the hemlocks. These grand old trees

seem to bury their dead decently, and long hillocks in the mossy carpet

alone mark their ancestors' graves, which are generally further adorned

by the evergreen tresses of the creeping partridge-berry, or the still

more delicate festoons of the capillaire.

The busy occupation of

all available space in the American forest by a great variety of shrubs

and herbaceous plants, constitutes one of its principal charms—the

multitudes of blossoms and delicate verdure arising from the sea of moss

to greet our eyes in spring, little maple or birch seedlings starting up

from prostrate trunks or crannies of rock boulders, with wood violets,

and a host of the spring flora. The latter, otherwise rough and

shapeless objects, are thus invested with a most pleasing

appearance—transformed into the natural flower vases of the woods. The

abundance of the fern tribe, again, lends much grace to the woodland

scenery. In the swamp the cinnamon fern, 0. cinnamomea, with 0.

interrupta, attain a luxuriant growth; and the forest brook is often

almost concealed by rank' bushes of royal fern (0. regalis). Eocks in

woods are always topped with polypodium, whilst the delicate fronds of

the oak fern hang from their sides. Filix foemina and F. mas are common

everywhere, and, with many others of the list, present apparently

inappreciable differences to their European representatives.

There is a beauty

peculiar to this interesting order especially pleasing to the eye when

studying details of a landscape in which the various forms of vegetation

form the leading features. The luxuriant mosses and great lichens which

cover or cling to everything in the forest act a similar part. Even the

dismal black swamps are somewhat enlivened by the long beards of the

Usnea; fallen trees are often made quite brilliant by a profusion of

scarlet cups of Cladonia gracilis.

But now let us examine

further into the specific character of at least some of the individuals

of which the forest is composed. As we wander on we chance, perhaps, to

stumble upon what is called, in woodsman’s parlance, a “ blazed line ”—a

broad chip has been cut from the side of a tree, and the white surface

of the inner wood at once catches the eye of the watchful traveller; a

few paces farther on some saplings have been cut, and, keeping the

direction, we perceive in the distance another blazed mark on a trunk.

It may be a path leading from the settlement to some distant woodland

meadow of wild grass, or a line marking granted property, or it may lead

to a lot of timber trees marked for the destructive axe of the lumberer—perhaps

a grove of White Pine. This is the great object of the lumberer’s

search. Ascending a tree from which an extensive view of the wild

country is commanded, he marks the tall overbearing summits of some

distant pine grove (for this tree is singularly gregarious, and is

generally found growing in family groups), and having taken its bearings

with a compass, descends, and with his comrades proceeds on his errand

of destruction. In the neighbourhood of the coast, or on barren soil,

the pine is a stunted bushy tree, its branches feathering nearly to the

ground; but the pine of the forest ascends as a straight tower to the

height of some 120 feet, two or three massive branches being thrown out

in twisted and fantastic attitudes. As if aware of its proud position as

monarch of the forest, it is often found on the summit of a precipice ;

and these conspicuous positions, which it seems to prefer, have doomed

this noble specimen of the cone-bearing evergreens to ultimate

extermination as certain as that of the red man or the larger game of

this continent. Some half-century since, the pine was found on the

margins of all the large lakes and streams, but of late the axe and

devastating fires have, as it were, driven the tree far back into the

remoter solitudes of the forest, and long and expensive expeditions must

be undertaken ere the head-quarters of a gang of lumber-men can be fixed

upon for a winter employment. At the head waters of some insignificant

brook, and in the neighbourhood of good timber, these hardy sons of the

forest fell the trees, and cut and square them into logs, dragging them

to the edge of the stream, into whose swollen waters they are rolled at

the breaking up of winter and melting of the snow, to find their way

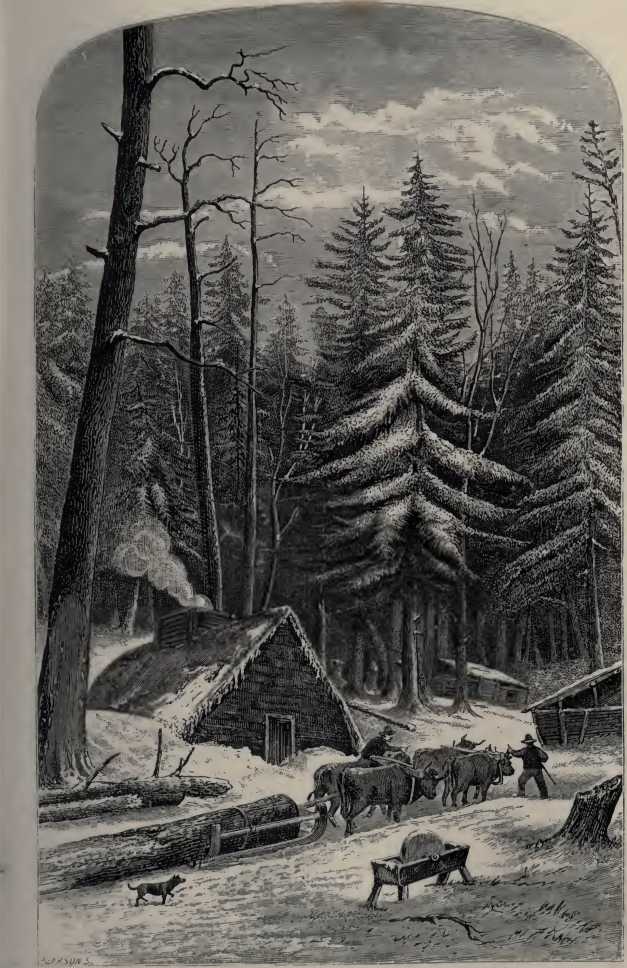

through almost endless difficulties to the sea. That most useful animal

in the woods, the ox, accompanies the lumberers to their remote forest

camps, and drags the logs to the side of the stream. It is really

wonderful to watch these animals, well managed, performing their

laborious tasks in the forest: urged on and directed solely by the

encouraging voice of the teamster, the honest team drag the huge

pine-log over the rough inequalities of the ground, over rocks, and

through treacherous swamps and thickets, with almost unaccountable ease

and safety, where the horse would at once become confused, frightened,

and injured, besides falling on

THE LUMBERER’S CAMP IN WINTER.

the score of

comparative strength. Slowly but surely the ox performs incredible feats

of draught in the woods, and asks for no more care than the shelter of a

rough shed near the lumberers’ camp, with a store of coarse wild hay,

and a drink at the neighbouring brook.

This aristocrat of the

forest, Pinus strobus, refuses to grow in the black swamp or open bog,

which it leaves to poverty-stricken spruces and larches, nor in its

communities will it tolerate much undergrowth. Pine woods are peculiarly

open and easy to traverse. Bracken, and but little else, grows beneath,

and the foot treads noiselessly on a soft slippery surface of fallen

tassels. A peculiarly soft subdued light pervades these groves—a ray

here and there falling on the white blossoms of the pigeon berry (Cornus

Canadensis) in summer, or, later, on its bright scarlet clusters of

berries, sets frequent sparkling gems in our path. That beautiful forest

music termed soughing in Scotland, in reference to the sound of the wind

passing over the foliage of the Scotch fir, is heard to perfection

amongst the American pines.

The white pine,

according to Sir J. Eichardson, ranges as far to the north ward as the

south shore of Lake Wini-peg. “ Even in its northern termination,” he

says, “ it is still a stately tree."

The Hemlock, or Hemlock

Spruce (Abies Canadensis of Michaux), is a common tree in the woodlands

of Acadie, affecting moist mossy slopes in the neighbourhood of lakes,

though generally mixing with other evergreens in all situations. It is

found, however, of largest growth (80 feet), and growing in large

groves, principally in the former localities, where it vies with the

white pine in its solid proportions. The deeply grained columnar trunk

throws off its first branches some 50 feet above the ground, and the

light feathery foliage clings round the summit of an old tree in dense

masses, from which protrude the bare twisted limbs which abruptly

terminate the column.

Perched high up in its

branches may be often seen in winter the sluggish porcupine, whose

presence aloft is first detected by the keen eye of the Indian through

the scratches made by its claws on the trunk in ascending its favourite

tree to feed on the bark and leaves of the younger shoots.

Large groves of hemlock

growing on woodland slopes present a noble appearance; their tall

columns never bend before the gale. There is a general absence of

undergrowth, thus affording long vistas through the shady grove of

giants; and the softened light invests the interior of these vast forest

cathedrals with an air of solemn mystery, whilst the even spread of

their mossy carpet affords appreciable relief to the footsore hunter.

The human voice sounds as if confined within spacious and lofty halls.

Hawthorne, describing

the wooded solitudes in which he loved to wander, thus speaks of a grove

of these trees :—“These ancient hemlocks are rich in many things beside

birds. Indeed, their wealth in this respect is owing mainly, no doubt,

to their rank vegetable growths, their fruitful swamps, and their dark,

sheltered retreats.

“Their history is of an

heroic cast. Kavished and torn by the tanner in his thirst for bark,

preyed upon by the lumberman, assaulted and beaten back by the settler,

still their spirit has never been broken, their energies never paralysed.

Not many years ago a public highway passed through them, but it was at

no time a tolerable road ; trees fell across it, mud and limbs choked it

up, till finally travellers took the hint and went around ; and now,

walking along its deserted course, I see only the footprints of coons,

foxes, and squirrels.

“Nature loves such

woods, and places her own seal upon them. Here she shows me what can be

done with ferns and mosses and lichens. The soil is marrowy and full of

innumerable forests. Standing in these fragrant aisles, I feel the

strength of the vegetable kingdom and am awed by the deep and

inscrutable processes of life going on so silently about me.

“No hostile forms with

axe or spud now visit these solitudes. The cows have half-hidden ways

through them, and know where the best browsing is to be had. In spring

the farmer repairs to their bordering of maples to make sugar; in July

and August women and boys from all the country about penetrate the old

Barkpeeling for raspberries and blackberries; and I know a youth who

wonderingly follows their languid stream casting for trout.

“In like spirit, alert

and buoyant, on this bright June morning go I also to reap my

harvest,—pursuing a sweet more delectable than sugar, fruit more savoury

than berries, and game for another palate than that tickled by trout".

Hemlock bark,

possessing highly astringent properties, is much used in America for

tanning purposes, almost entirely superseding that of the oak. Its

surface is very rough with deep grooves between the scales. Of a light

pearly gray outside, it shows a madder brown tint when chipped. The

sojourner in the woods seeks the dry and easily detached bark which

clings to an old dead hemlock as a great auxiliary to his stock of fuel

for the camp fire; it burns readily and long, emitting an intense heat,

and so fond are the old Indians of sitting round a small conical pile of

the ignited bark in their wigwams, that it bears in their language the

sobriquet of “the old Grannie.”

The hemlock, as a

shrub, is perhaps the most ornamental of all the North American

evergreens. It has none of that tight, stiff, old-fashioned appearance

so generally seen in other spruces: the graceful foliage droops loosely

and irregularly, hiding the stem, and, when each spray is tipped with

the new season's shoot of the brightest Sea-green imaginable, the

appearance is very beautiful. The young cones are likewise of a delicate

green.

This tree has a wide

range in the coniferous woodlands of North America, extending from the

Hudson's Bay territory to the mountains of Georgia. The great southerly

extension of the northern forms of trees on the south-east coast, is due

to the direction of the Alleghanian range, which, commencing in our own

province of vegetation, carries its flora as far south as 35 degrees

north latitude, elevation affording the same conditions of growth as

distance from the equator.

It would appear that

this giant spruce has no analogous form in the Old World as have others

of the genus Abies found in the New. All the genera of conifers,

however, here contain a larger number of trees, which, though they are

exceedingly similar in general appearance, are specifically distinct

from their European congeners.

Under the Arctic

circle, as pointed out by Sir J. Richardson, and beyond the limits of

tree growth, but little appreciable difference exists in circumpolar

vegetation, and so we recognise in the luxuriant eryptogamous flora of

the forests we are describing most of the mosses and lichens found

across the Atlantic, which here attain such a noticeable development. As

with nobler forms, America, however, adds many new species to the list.

.

The Black Spruce is one

of the most conspicuous and characteristic 1 forest trees of

North-Eastern America, forming a large portion of the coniferous forest

growth, and found in almost every variety of circumstance. Sometimes it

appears in mixed woods, of beautiful growth and of great height, its

numerous branches drooping in graceful curves from the apex towards the

ground, which they sweep to a distance of twenty to thirty feet from the

stem, whilst the summit terminates in a dense arrow head, on the short

sprays of which are crowded heavy masses of cones. At others, it is

found almost the sole growth, covering large tracts of country, the

trees standing thick, with straight clean stems and but little foliage

except at the summit. Then there is the black spruce swamp, where the

tree shows by its contortions, its unhealthy foliage, and its stem and

limbs shaggy with usnea, the hardships of its existence. Again on the

open bog grows the black spruce, scarcely higher than a cabbage sprout

—the light olive-green foliage living on the compressed summit only,

whilst the grey dead twigs below are crowded with pendulous moss; yet

even here, amidst the cold sphagnum, Indian cups, and cotton grass, the

tree lives to an age which would have given it a proud position in the

dry forest. Lastly, in the fissure of a granite boulder may be seen its

hardy seedling; and the little plant has a far better chance of becoming

a tree than its brethren in the swamp; for, one day, as frost and

increasing soil open the fissure, its roots will creep out and fasten in

the earth beneath.

In unhealthy situations

a singular appearance is frequently assumed by this tree. Stunted, of

course, it throws out its arms in the most tortuous shapes, suddenly

terminating in a dense mass of innumerable branchlets of a rounded

contour like a beehive, displaying short, thick, light green foliage.

The summit of the tree generally terminates in another bunch. The stem

and arms are profusely covered with lichens and usnea. As a valuable

timber tree the black spruce ranks next to the pine, attaining a height

of seventy to a hundred feet. Being strong and elastic, it forms

excellent material for spars and masts, and is converted into all

descriptions of sawed lumber—deals, boards, and scantlings. From its

young sprays is prepared the decoction, fermented with molasses, the

celebrated spruce beer of the American settler, a cask of which every

good farmer’s wife keeps in the hot, thirsty days of haymaking. To the

Indian, the roots of this tree, which shoot out to a great distance

immediately under the moss, are his rope, string and thread. With them

he ties his bundle, fastens the birch-bark coverings to the poles of his

wigwam, or sews the broad sheets of the same material over the ashen

ribs of his canoe.

For ornamental purposes

in the open and cultivated glebe the black spruce is very appropriate.

The numerous and gracefully curved branches, the regular and acute cone

shape of the mass, its clear purplish-grey stem, and the beautiful bloom

with which its abundant cones are tinged in June, all enhance the

picturesqueness of a tree which is long-lived, and, moreover, never

outgrows its ornamental appearance, unless confined in dense woodland

swamps.

The bark of the black

spruce is scaly, of various shades of purplish-grey, sometimes

approaching to a reddish hue, hence, doubtless, suggesting a variety

under the name of red spruce, which is in reality a form depending on

situation. In the latter, the foliage being frequently of a lighter

tinge of green, strengthens the supposition. No specific differences

have, however, been detected between the trees.

The White Spruce or Sea

Spruce of the Indians (Abies alba, Mich.) is a conifer of an essentially

boreal character. Indeed in its extension into our own woodlands it

appears to prefer bleak and exposed situations. It thrives on our rugged

Atlantic shores, and grows on exposed and brine-washed sands where no

other vegetation appears, and hence is very useful, both as a shelter to

the land, and as holding it against the encroachment of the sea. Its

dark glaucous foliage assumes an almost impenetrable aspect under these

circumstances. I have seen groves of white spruce on the shore, the

foliage of which was swept back over the land by prevailing gales from

the south-west, nearly parallel to the ground, and so compressed and

flattened at the top that a man could walk on them as on a platform,

whilst the shelter beneath was complete.

The Balsam Fir growing

in these situations assumes a very similar appearance in the density and

colour of its foliage and trunk to the white spruce, from which,

however, it can be quickly distinguished, on inspection, by the pustules

on the bark and its erect cones. In the forest the white spruce is rare

in comparison with the black, whose place it however altogether usurps

on the sand hills bordering the limit of vegetation in the far

north-west. The former tree prefers humid and rocky woods.

Our Silver Fir (Abies

balsamea, Marshall) is so like the European picea that they would pass

for the same species were it not for the balsam pustules which

characterise the American tree. Both show the same silvery lines under

the leaf on each side of the mid-rib, which, glistening in the sun as

the branches are blown upwards by the wind, give the tree its name. We

find it in moist woods—growing occasionally in the provinces to a height

of sixty feet where it has plenty of room—a handsome, dark-foliaged

tree; short-lived, however, and often falling before a heavy gale,

showing a rotten heart.

The silver fir is

remarkable for the horizontal regularity of its branches, and the

general exact conical formation of the whole tree. An irregularity in

the growth of the foliage, similar to that occurring in the black

spruce, is frequently to be found in the fir. A contorted branch,

generally half-way up the stem, terminates in a multitude of interlaced

sprays which are, every summer, clothed with very delicate, flaccid,

light-green leaves, forming a beehive shape like that of the spruce. It

may be noticed, however, that whilst this bunch foliage is perennial in

the case of the latter tree, that of the fir is annually deciduous. Up

to a certain age the silver fir in the forest is a graceful shrub. Its

flat delicate sprays form the best bedding for the woodman's couch; the

fragrance of its branches, when long cut or exposed to the sun, is

delicious, and their soft elasticity is most grateful to the limbs of

the wearied hunter on his return to camp. The bark of the larger trees,

peeling readily in summer, is used in sheets to cover the lumberer's

shanty, which he now takes the opportunity to build in prospect of the

winter’s campaign.

The large, erect,

sessile cones of the balsam fir are very beautiful in the end of May,

when they are of a light sea-green colour, which, changing in June to

pale lavender, in August assumes a dark slaty tint. They ripen in the

fall; and the scale being easily detached, the seeds are soon scattered

by the autumnal gales, leaving the axis bare and persistent on the

branch for many years. In June each strobile is surmounted with a large

mass of balsam exudation.

A casual observer, on

passing the edges of the forest, cannot help remarking the brown

appearance of the spruce tops in some seasons when the cones are

unusually abundant. They are crowded together in bushels, and often kill

the upper part of .the tree and its leading shoot, after which a new

leader appears to be elected amongst the nearest tier of branchlets to

continue the upward growth. From such a crop the Indians augur an

unusually hard winter, through much the same process of reasoning as

that which the English countryman adopts in prophesying a rigorous

season from an abundant crop of haws and other autumnal hedge fruits,

and generally with about the same chance of fulfilment.

No less majestic than

the coniferse are many of the species of deciduous trees, or “hard

woods,” which, intermingled with the former, impart such a pleasing

aspect to the otherwise gloomy fir forests of British North America.

Growing, as the firs, with tall straight stems, and struggling upwards

for the influence of the sunlight on their lofty foliage, the yellow and

black birches aspire to the greatest elevation, attaining a height of

seventy or eighty feet. Mixed with these are beeches and elms; and in

many districts the country is covered with an almost exclusive growth of

the useful rock or sugar-maple.

In these <e mixed

woods,” as they are locally termed (indicative, it is said, of a good

soil), the prettiest contrast is afforded by the pure white stems of the

canoe birch (Betula papyracea) against the spruce boughs; and, as these

are generally open woods, the latter come sweeping down to the ground.

The young stems of the yellow birch (B. excelsa) gleam like gilded rods

in sunlight; their shining yellow bark looks as though it had been fresh

coated with varnish.

These American birches

are a beautiful family of trees, particularly the canoe or paper birch,

so called from the readiness with which its folds of bark will separate

from the stem like thick sheets of paper. Smooth and round, without a

knot or branch for some forty feet from the ground, is the tree which

the Indian anxiously looks for; it affords him the broad sheets of bark

which cover his wigwam and the frame of his canoe, and long journeys

does he often undertake in search of it. The bark is thick as leather,

and as pliable, and in the summer can readily be separated for any

distance up the stem. From it the Indians make the boxes and

curiosities, by the sale of which these poor creatures endeavour to earn

a livelihood. Their fanciful goods cannot, however, compete with the

useful productions of civilised labour, and are only bought by the

stranger and the charitable. The white birch of the forest is as closely

connected with the interests of the Indian as the pine is with those of

the lumberer, and the former dreads the ultimate comparative scarcity of

the birch as the latter does that of the noble timber-tree.

From the mountains of

Virginia, on the south-east, this important tree ranges northwardly in

Atlantic America far into the interior of Labrador, whilst in the

extreme north-west it ascends the valley of the Mackenzie as far as 69

degrees N. lat.

In travelling the

forest in summer it is quite refreshing to enter the bright sheen of a

birch-covered hill, exchanging the close resinous atmosphere of heated

fir-woods for its cool open vaults. The transition is often quite sudden

—the scene changing from gloom to brightness with a magical effect. Such

a contrast is presented to the marked lights and shades of the pine

forest! The silvery stems with their light canopy of sunlit leaves,

through the breaks in which the blue sky shows quite dark as a

background, the innumerable lights falling on the light green

undergrowth of plants and shrubs beneath, and the general absence of

appreciable lines of shadow everywhere, stamp these hard-wood hills with

an almost fairyland appearance.

If at all near the

borders of civilisation, we soon strike a “hauling road,” leading from

such localities into the settlements—a track broad enough for a sled and

pair of oxen to pass over when the farmer comes in winter to transport

his firewood over the snow. And a goodly stock indeed he requires to

battle with the cold of a North American winter in the backwoods; logs,

such as it would take two men to lift, of birch, beech or maple, are

piled on his ample hearth; the abundance of fuel and the readiness with

which he can bring it from the neighbouring bush, is one of his greatest

blessings. He deserves a few comforts, for perhaps his lifetime, and

that of his father, has been spent in redeeming the few acres round the

dwelling from the fangs of gigantic stumps and boulders of rock. A patch

of potatoes, an acre or so of buckwheat, and another of oats, and a few

rough-looking cattle, are his sources of wealth, or perhaps a rough saw

mill, constructed far up in the forest brook, and the whirr of whose

circular saw disturbs only the wild animals of the surrounding woods.

How vividly is recalled

to my memory the delight experienced on many occasions by our tired,

belated party, returning from a hunting camp through unknown woods, on

finding one of these logging roads, anticipating in advance the kindly

welcome of the invariably hospitable backwoods farmer, towards whose

clearings it was sure to trend. Perhaps for hours before we had almost

despaired of quitting the forest by nightfall. On sending the Indians

into tree-tops to reconnoitre, the disheartening cry would be, “Woods

all round as far as we can see.” Further on, perhaps, we should hear

that there were “Lakes all round!” Worse again, for then a wearisome

detour must be made. But at last some one finds signs of chopping, then

a stack of cord-wood, and then we strike a regular blazed line. Now the

spirits of every one revive, and we soon emerge on the forest road with

its clean-cut track, corduroy platforms through swamps, and rude log

bridges over the brooks, which brings us within the welcome sound of

cattle bells, and at length to the broad glare of the clearings.

Before leaving the

woods, however, we may not omit to notice those characteristic trees of

the American forest, the maples, particularly that most important member

of the family, the rock or sugar maple—Acer saccharinum. Found generally

interspersed with other hard-wood trees, this tree is seen of largest

and most frequent growth in the Acadian forests on the slopes of the

Cobequid hills, and other similar ranges in Nova Scotia, often growing

together in large clumps. Such groves are termed “Sugaries,” and are

yearly visited by the settlers for the plentiful supply of sap which, in

the early spring, courses between the bark and the wood, and from which

the maple sugar is extracted. Towards the end of March, when winter is

relaxing its hold, and the hitherto frozen trees begin to feel the

influence of the sun, the settlers, old and young, turn into the woods

with their axes, sap-troughs, and boilers, and commence the operation of

sugar-making. A fine young maple is selected; an oblique incision made

by two strokes of the axe at a few feet from the ground, and the pent-up

sap immediately begins to trickle and drop from the wound. A wooden

spout is driven in, and the trough placed underneath; next morning a

bucketful of clear sweet sap is removed and taken to the boiling-house.

Sometimes two or three hundred trees are tapped at a time, and require

the attention of a large party of men. At the camp, the sap is carefully

boiled and evaporated until it attains the consistency of syrup. At this

stage much of it is used by the settlers under the name of “maple honey,

or molasses.” Further boiling; and on pouring small quantities on to'

pieces of ice, it suddenly cools and contracts, and in this stage is

called “ maple-wax,” which is much prized as a sweetmeat. Just beyond

this point the remaining sap is poured into moulds, in which as it cools

it forms the solid saccharine mass termed “maple sugar.” Sugar may also

be obtained, though inferior in quality, from the various birches; but

the sap of these trees is slightly acidulous, and is more often

converted into vinegar.

White or soft maple (A.

dasycarpum), and the red flowering maple (A. rubrum), are equally common

trees. Both contribute largely to the gorgeous colouring of the fall,

and the latter species clothes its leafless sprays in the spring almost

as brilliantly with scarlet blossoms. Before these fade, a circlet of

light green leaves appears below, when a terminal shoot has a fitting

place in an ornamental bouquet of spring flowers.

As a rule, all the

Aceracese are noted for breadth of leaf, and, being even more abundant

than the birches in the forests of Acadie, the solid appearance of the

rolling hard-wood hills is thus accounted for. These great swelling

billows in a sea of verdure form the grandest feature of American forest

scenery. In Vermont and New Hampshire, to the westward of our provinces,

they become perfectly tempestuous. The black arrow-heads of the spruces,

or the slanting tops of the pines, pierce through them distinctly

enough, but the summits of the hard-woods are blended together in one

vast canopy of light green foliage, in which the eye vainly seeks to

trace individual form.

Amongst the varieties

of scenery presented by our wild districts, I would notice the burnt

barrens. These sometimes extend for many miles, and are most dreary in

their appearance and painfully tedious to travel through. Years ago,

perhaps, some fierce fire has run through the evergreen forest, and its

ravages are now shown in the spectacle before us. Gaunt white stems

stand in groups, presenting a most ghost-like appearance, and pointing

with their bleached branches at the prostrate remains of their

companions, which, strewed and mixed with matted bushes and briars, lie

beneath, rendering progress almost impossible to the hunter or traveller.

In granitic districts,

where the scanty soil—the result of ages of cryptogamous vegetation and

decay—has been clean licked up by the fire, even the energetic power of

American vegetation appears utterly prostrated for a period, as if

hopeless of again assimilating the desert to the standard of surrounding

features.

As a contrast to such a

scene, and in conclusion to our dissertation on the forests, turn we to

the smiling intervale scenery of her alluvial valleys, for which Acadie

is so famous. Many of the rivers, coursing smoothly through long tracts

of the country, are broadly margined by level meadows with rich soils,

productive of excellent pasture. The banks are adorned with orange

lilies; and the meadows, which extend between the water and the uplands,

shaded by clumps of elm (Ulmus americana).

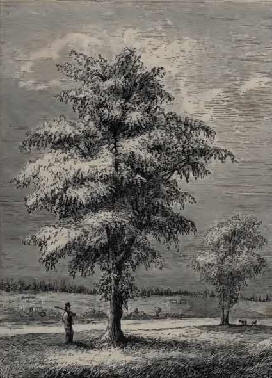

Almost the whole charm

of these intervales (in an artistic point of view) is due to the groups

of this graceful tree, by which they are adorned. Its stem, soon forking

and diverging like that of the English hornbeam, nevertheless carries

the main bulk of the foliage to a good elevation, the ends of the middle

and lower branches bending gracefully downwards. The latter often hang

for several yards, quite perpendicularly, with most delicate hair-like

branchlets and small leaves. We have but one elm in this part of

America; yet no one at first sight would ever connect the tall trunk and

twisted top branches of the forest-growing tree with the elegant form of

the dweller in the pasture lands.

Whether from

appreciation of its beauty, or in view of the shade afforded their

cattle, which always congregate in warm weather under its pendulous

branches, the settlers agree in sparing the elm growing in such

situations.

These long fertile

valleys are further adorned by copses of alders, dogwood, and willows—favourite

haunts of the American woodcock, which here alone finds subsistence, the

earth-worm being never met with in the forest.

ELMS IN AN INTERVALE.

|