|

THE MOOSE

{Alee, Hamilton Smith; Alee Americanus, Jardine.)

Muzzle very broad,

produced, covered with hair, except a small, moist, naked spot in front

of the nostrils. Neck short and thick; hair thick and brittle; throat

rather maned in both sexes; hind legs have the tuft of hair rather above

the middle of the metatarsus; the males have palmate horns. The nose

cavity in the skull is very large, reaching behind to a line over the

front of the grinders; the inter-maxillaries are very long, but do not

reach to the nasal. The nasals are very short.

In the foregoing

diagnosis, taken from “GraysKnowsley Menagerie,” are summed up the

principal characteristics of the elk in the Old and New Worlds. In

colour alone the American moose presents an unimportant difference to

the Swedish elk; being much darker; its coat at the close of summer

quite black, when the males are in their prime. The European animal

varies according Jo season from brown to dark mouse-grey. In old bulls

of the American variety the coat is inclined to assume a grizzly hue.

The extremities only of the hairs are black; towards the centre they

become of a light ashy-grey, and finally, towards the roots, dull

white—the difference of colour in the hair of the two varieties thus

being quite superficial. The males have a fleshy appendage to the

throat, termed the bell, from which and the contiguous parts of the

throat long black hair grows profusely. A long, erect mane surmounts the

neck from the base of the skull to the withers. Its bristles are of a

lighter colour than those of the coat, and partake of a reddish hue. At

the base of the hair the neck and shoulders are covered with a quantity

of very fine soft wool, curled and interwoven with the hair. Of this

down warm gloves of an extraordinarily soft texture are woven by the

Indians.

Moose hair is very

brittle and inelastic. Towards its junction with the skin it becomes

wavy, the barrel of each hair suddenly contracting like the handle of an

oar just before it enters the skin.

Gilbert White, speaking

of a female moose deer which he had inspected, says: “The grand

distinction between this deer and any other species that I have ever met

with consisted in the strange length of its legs, on which it was tilted

up, much in the manner of birds of the grallse order.” This length of

limb is due, according to Professor Owen, “to the peculiar length of the

cannon bones (metacarpi and metatarsi).”

The other noticeable

peculiarities of the elk are the great length of the head and ear, and

the muscular development of the upper lip; the movements of which,

directed by four powerful muscles arising from the maxil-laries, prove

its fitness as a prehensile organ. In form it has been said to be

intermediate between the snout of the horse and of the tapir. I am

indebted to Mr. Buck-land for the following description of a skull,

which had been forwarded to him from Nova Scotia :—

“This splendid skull

weighs ten pounds eleven ounces, and is twenty-four inches and a-half in

length. The inter-maxillary bones are very much, prolonged, to give

attachment to the great muscle or upper prehensile lip, and the foramen

in the bone for the nerve, which supplies the ‘muffle’ with sensation,

is very large. I can almost get my little finger into it. The ethmoid

bone, upon which the nerves of smelling ramify themselves, is very much

developed. No wonder the hunter has such difficulty in getting near a

beast whose nose will telegraph the signal of dangers to the brain, even

when the danger is a long way off, and the ‘walking danger' if I have

read the habits of North American Indians, is in itself of a highly

odoriferous character. The cavities for the eyes are wide and deep. I

should say the moose has great mobility of the eye. The cavity for the

peculiar gland in front of the eye is greatly scooped out. The process

at the back of the head for the attachment of the ligamentum nuchse—the

elastic ligament which, like an india-rubber spring, supports the weight

of the massive head and ponderous horns without fatigue to the owner, is

much developed. The enamel on the molar teeth forms islands with the

dentine somewhat like the pattern of the tooth of the common cow.”

The height of the elk

at the withers but little exceeds that at the buttock; the back

consequently has not that slope to the rear so often misrepresented in

drawings of the animal. The appearance of extra height forwards is given

by the mane, which stands out from the ridge of the neck, something like

the bristles of an inverted hearth-broom. The ears, which are

considerably over a foot in length in the adult animal, are of a light

brown, with a narrow marginal dark-brown rim; the cavity is filled with

thick whitish-yellow hair. The naked skin fringing the orbit of the eye

is a dull pink; the eye itself of a dark sepia colour. Under the orbit

there is an arc of very dark hair. The lashes of the upper lid are full,

and rather over an inch in length. A large specimen will measure six

feet six inches in height at the shoulder; length of head from occiput

to point of muffle, following the curve, thirty-one inches; from occiput

to top of withers in a straight line, twenty-nine inches ; and from the

last point horizontally to a vertical tangent of the buttocks, fifty-two

inches. A large number of measurements in my possession, for the

accuracy of which I can vouch, show much variation of the length of back

in proportion to the height, thus probably accounting for a commonly

received opinion amongst the white settlers of the backwoods that there

are two varieties of the moose.

The study of northern

zoology presents a variety of considerations interesting both to the

student of recent nature and to the palaeontologist. Taking as well

known instances the reindeer and musk-ox, there are’ forms yet

inhabiting the arctic and sub-arctic regions which may be justly

regarded as the remains of an ancient fauna which once comprised many

species now long since extinct, and which with those already named,

occupied a far greater southerly extent of each of the continents

converging on the pole than would be possible under the present climatal

conditions of the world. With those great types which have entirely

disappeared before man had recorded their existence in the pages of

history, including the mammoth (Elephas primigenius), the most abundant

of the fossil pachyderms, whose bones so crowd the beaches and islands

of the Polar Sea that in parts the soil seems altogether composed of

them, the Ehinoceros tichorinus, and others, were associated genera, a

few species of which lived on into the historic period, and have since

become extinct, whilst others, occupying restricted territory, are

apparently on the verge of disappearance. “All the species of European

pliocene bovidae came down to the historical period,” states Professor

Owen in his “British Fossil Mammals“ and the aurochs and musk-ox still

exist; but the one owes its preservation to special imperial protection,

and the other has been driven, like the reindeer, to high northern

latitudes." Well authenticated as is the occurrence of the rangifer as a

fossil deer of the upper tertiaries, the evidence of its association in

ages so remote, with Cervus Alces, has been somewhat a matter of doubt.

The elk and the reindeer have always been associated in descriptions of

the zoology of high latitudes by modern naturalists, as they were when

the boreal climate, coniferous forests, and mossy bogs of ancient Gaul

brought them under notice of the classic pens of Caesar, Pausanias, and

Pliny. And there is a something in common to both of these singular deer

which would seem to connect them equally with the period when they and

the gigantic contemporary genera now extinct roamed over so large a

portion of the earth's surface in the north temperate zone, where the

fir-tree—itself geologically typical of a great antiquity—constituted a

predominant vegetation.

The presence of the

remains of Cervus Alces in association with those of the mammoth, the

great fossil musk-ox (Ovibos), the fossil reindeer, and two forms of

bison in the fossiliferous ice-cliffs of Eschscholtz Bay, as described

by Sir John Eichardson, would seem to be an almost decisive proof of its

existence at a time when the temperature on the shores of the Polar Sea

was sufficiently genial to allow of a vegetation affording browse and

cover to the great herds of mammals which have left their bones there,

with Buried, fossilised trees, attesting the presence of a forest at. a

latitude now unapproached save by shrubs, such as the dwarf birch, and

by that only at a considerable distance to the south. The elk of the

present day, as we understand his habits, unlike the musk-ox and

reindeer, for which lichens and scanty grasses in the valleys of the

barren grounds under the Polar circle afford a sufficient sustenance, is

almost exclusively a wood-eater, and could not have lived at the

locality above indicated under the present physical aspects of the

coasts of Arctic America, any more than the herds of buffaloes, horses,

oxen and sheep, whose remains are mentioned by Admiral Yon Wrangell as

having been found in the greatest, profusion in the interior of the

islands of New Siberia, associated with mammoth bones, could now exist

in that icy wilderness. On these grounds a high antiquity is claimed for

the sub-genus Alces, probably as great as that of the reindeer.

As a British fossil

mammal, the true elk has not yet been described, though for a long time

the remains of the now well-defined sub-genus Megaceros were ascribed to

the former animal. There is a statement, however, in a recent volume of

the “Zoologist” to the effect that the painting of a deers head and

horns, which were dug out of a marl pit in Forfarshire, and presented to

the Royal Society of Edinburgh, is referable to neither the fallow, red,

nor extinct Irish deer, but to the elk, which may be therefore regarded

as having once inhabited Scotland. The only recorded instance of its

occurrence in England is the discovery, a few years since, of a single

horn at the bottom of a bog on the Tyne. It was found lying on, not in,

the drift, and therefore can be only regarded as recent.

Passing on to

prehistoric times, when the remains of the species found in connexion

with human implements prove its subserviency as an article of food to

the hunters of old, we find the bones of Cervus Alces in the Swiss lake

dwellings, and the refuse-heaps of that age; whilst in a recent work on

travel in Palestine by the Rev. H. B. Tristram, we have evidence of the

great and ancient fauna which then overspread temperate Europe and Asia

having had a yet more southerly extension, for he discovers a limestone

cavern in the Lebanon, near Beyrout, containing a breccious deposit

teeming with the debris of the feasts of prehistoric man—flint

chippings, evidently used as knives, mixed with bones in fragments and

teeth, assignable to red or reindeer, a bison, and an elk. “If,” says

the author, “as Mr. Dawkins considers, these teeth are referable to

those now exclusively northern quadrupeds, we have evidence of the

reindeer and elk having been the food of man in the Lebanon not long

before the historic period; for there is no necessity to put back to any

date of immeasurable antiquity the deposition of these remains in a

limestone cavern. And,” he adds, with significant reference to the great

extension of the ancient zoological province of which we are speaking,

“there is nothing more extraordinary in this occurrence than in the

discovery of the bones of the tailless hare of Siberia in the breccias

of Sardinia and Corsica.”

The first allusion to

the elk in the pages of history is made by Caesar in the sixth book “De

Bello Gallico”— “sunt item qiicB appellantur Alces” etc. etc., a

description of an animal inhabiting the great Iiercynian forest of

ancient Germany, in common with some other remarkable ferae, also

mentioned, which can refer to no other, the name being evidently

Latinised from the old Teutonic cognomen of elg, elch, or aelg, whence

also our own term elk. He speaks of the forest as commencing near the

territories of the Helvetii, and extending eastward along the Danube to

the country inhabited by the Dacians. “Under this general name,” says

Dr. Smith, “Caesar appears to have included all the mountains and

forests in the south and centre of Germany, the Black Forest, Odenwald,

Thiiringenwald, the Hartz, the Erzgebirge, the Eiesengebirge, etc., etc.

As the Eomans became better acquainted with Germany, ‘ the name was

confined to narrower limits. Pliny and Tacitus use it to indicate Jhe

range of mountains between the Thiiringenwald and the Carpathians. The

name is still preserved in the modem Harz and Erz.” Gronovius states

that the German word was Hirtsenwald, or forest of stags. In an old

translation of the Commentaries I find the word “alces” rendered a kind

of wild asses, and really a better term could hardly be applied, had the

writer, unacquainted with the animal, caught a passing glimpse of an

elk, especially of a young one without horns. But it is evident that

Caesar alludes to a large species of deer, and, although he compares

them to goats (it is nearly certain that the original word was

“capreis,” “caprea” being a kind of wild goat or roebuck), and received

from his informants the story of their being jointless—an attribute, in

those days of popular errors and superstitions, ascribed to other

animals as well—the very fact of their being hunted in the manner

described, by weakening trees, so that the animal leaning against them,

would break them down, involving his own fall, proves that the alee was

a creature of ponderous bulk.

The descriptive

paragraph alluded to contains one of the fallacies which have always

been attached to the natural history of the elk, ancient and modem; and,

even now-a-days the singular appearance of the animal attempting to

browse on a low shrub close to the ground, his legs not bent at the

joint, but straddling stiffly as he endeavours to cull the morsel with

his long, prehensile upper lip, might impart to the ignorant observer

the idea that the stilt-like legs were jointless. The fabrication of

their being hunted in the way described was, of course, based on the

popular error as to the formation of their limbs. “Mutilceque sunt

cornibus” may imply that Caesar, or more likely some of his men, had

either seen a female elk, or—as might be more acceptably inferred—a male

which had lost one horn, and consequently late in the autumn, as it is

well known that the horns are not shed simultaneously. Pausanias speaks

of the elk as intermediate between the stag and the camel, as a most

sagacious animal, and capable of distinguishing the odour of a human

being at a great distance, taken by hunters in the same manner as is now

pursued in the “skall” of north Europe, and as being indigenous to the

country of the Celtae; whilst Pliny declares it to be a native of

Scandinavia, and states that at his time it had not been exhibited at

the Roman games. At a later period the animal became better known, for

Julius Capitolinus speaks of elks being shown by Gordian, and Vopiscus

mentions that Aurelian exhibited the rare spectacle of the elk, the

tiger, and the giraffe, when he triumphed over Zenobia.

In these few notices is

summed up all that has been preserved of what may be termed the ancient

history of the European elk. An interesting reflection is suggested as

to what were the physical features of central Europe in those days. It

seems evident that ancient France, then called Gaul, was a region of

alternate forests and morasses in which besides the red and the roe, the

reindeer abounded, if not the elk; that in crossing the Alps, a vast,

continuous forest, commencing on the confines of modern Switzerland,

occupied the valleys and slopes of the Alps, from the sources of the

Rhine to an eastern boundary indicated by the Carpathian mountains, and

embraced, as far as its northern extension was known, the plateau of

Bohemia. Strange and fierce animals, hitherto unknown to the

Romans—accustomed as they had been to seeing menageries of creatures

brought from other climes, dragged in processions and into the arena

—were found in these forests. The urus or wild bull, now long extinct,

“in size,” says Cfaesar, “little less than the elephant, and which

spares neither man nor beast when they have been presented to his view.”

The savage aurochs yet preserved in a Lithuanian forest, the elk and the

reindeer were their denizens, and formed the beef and venison on which

the fierce German hunters of old subsisted. “The hunting of that day”

may be well imagined to have been very different to the most exciting of

modern field sports, and continued down to the thirteenth century, as is

shown by the well-known passage from the Niebelungen poem, where the

hero, Sifrid, slays some of the great herbivorse—the bison, the elk, and

the urus— as well as “einen grimmen Schelch,” about the identity of

which so much doubt has arisen, though the conjecture has been offered

by Goldfuss, Major Hamilton Smith, and others, that the name refers to

no other than the great Irish elk or megaceros.

The recent notices of

the elk contained in some curious old works on the countries of northern

Europe and their natural history are valuable merely as indicating the

presence and range of the animal in certain regions. The errors and

extravagances of the classic naturalists still obtained, and tinged all

such writings to the commencement of the great epoch of modem natural

history ushered in by St. Hilaire and Cuvier. A confused account of the

animal is given by Scaliger, and it is mentioned by Gmelin in his

Asiatic travels. Olaus Magnus, the Swedish bishop, says, “The elks come

from the north, where the inhabitants call them clg or clges". SchefFer,

in his history of Lapland, published in 1701, speaks of that country “

as not containing many elks, but that they rather pass thither out of

Lithuania.” Other writers mention it, but, whenever a scientific

description is attempted it is full of credulous errors, such as its

liability to epileptic fits—a belief entertained not only by the

peasants of northern Europe, but likewise, with regard to the moose, by

the North American Indians; its attempt to relieve itself of the disease

by opening a vein behind the ear with the hind foot, whence pieces of

the hoof were worn by the peasants as a preventive against falling

sickness; and its being obliged to browse backwards through the upper

lip. becoming entangled with the teeth.* There are also ample notices of

the elk in the works of Pontoppidan and Nilsson; Albertus Magnus and

Gesner state that in the twelfth century it was met with in Sclavonia

and Hungary. The former writer calls it the equicervus or horse hart. In

1658 Edward Topsel published his te History of Fourfooted Beasts and

Serpents: to be procured at the Bible, on Ludgate-hill, and at the Key,

in Pauls Churchyard.” At page 165 he treats of the elk: “They are not

found but in the colder northern regions, as Eussia, Prussia, Hungaria,

and Illyria, in the wood; Hercynia, and among the Borussian Scythians,

but most plentiful in Scandinavia, which Pausanias calleth the Celtes ”

*Mr. Buckland,

referring to the above statement in “Land and Water,” says:—“Of course

some part of the elk was used medicinally. Our ancestors managed to get

a ‘pill et haustus’ out of all things, from vipers up to the moss in

human skulls. The Pharmacopoeia of the day prescribes a portion of the

hoof worn in a ring; ‘ it resisteth and freeth from the falling evil,

the cramp, and cureth the fits or pangs.' Fancy an hysterical lady being

told to take ‘elk’s hoof’ for a week, to be followed by ‘ hart’s horn.’

”

The accounts given by

the earlier American voyagers of Cervus Alces—there found under the

titles of moose (Indian) or Voriginal (French)—were also highly

exaggerated ; though, considering that they received their descriptions

from the Indians, who to this day believe in many romantic traditions

concerning the animal, they are excusable enough. From the writings of

Josselyn,1 Denys, Charlevoix, Le Hontan, and

others, little can be learnt of the natural history of the moose.

Suffice it to say, that they represented it as being ten or twelve feet

in height, with monstrous antlers, stalking through the forest and

browsing on the foliage at an astonishing elevation. It was consequently

long believed that the American animal was much larger than his European

congener ; and when the gigantic horns of the Megaceros were first

ascribed to an elk, it was to the former that they were referred by Dr.

Molyneux.

Commencing its modern

history, let us now briefly trace the limits within which the elk is

found in Europe, Asia, and—regarding the moose as at least congeneric—

America. It is to the sportsmen and naturalists who have recently

written on the field sports of the Scandinavian Peninsula that we are

indebted for nearly all our information on the natural history of this

animal, and its geographical distribution in northern Europe. The works

of Messrs. Lloyd and Barnard contain ample notices. “At the present

day,5' says the latter author, “ it is found in Sweden, south of the

province of East Gothland. Angermannland is its northernmost boundary.55

The late Mr. Wheelwright, in “ Ten Years in Sweden,55 which contains an

admirable synopsis of the fauna and flora of that country, places the

limits of the elk in Scandinavia between 58° North lat. and 64°. Mr.

Barnard states that “ it likewise inhabits Finland, Lithuania, and

Eussia, from the White Sea to the Caucasus. It is also found in the

forests of Siberia to the Eiver Lena, and in the neighbourhood of the

Altai mountains.55 Yon Wrangel met with the elk—though becoming scarce,

through excessive hunting and the desolation of the forest by fire—in

the Kolymsk district, in the almost extreme north-east of Siberia. Erman,

another eminent scientific traveller in Siberia, describes it as

abundant in the splendid pine forests which skirt the Obi, and mentions

it on several occasions in the narrative of his journey eastward through

the heart of the country to Okhotsk. It has been recently noticed

amongst the mammalia of Amoorland, and as principally inhabiting the

country round the lower Amoor. It is thus seen that the domains of the

elk in the Eastern Hemisphere are immensely extensive, lying between the

Arctic Circle—indeed, approaching the Arctic Ocean, where the great

rivers induce a northern extension of the wooded region—and the fiftieth

parallel of north latitude, from which, however, as it meets greater

civilisation in the western portion of the Russian empire, it recedes

towards the sixtieth.

In the New World, it

would appear from old narratives that the moose (as we must

unfortunately continue to call the elk, whose proper title has been

misappropriated to Cervus canadensis) once extended as far south as the

Ohio. Later accounts represent its southern limit on the Atlantic coast

to be the Bay of Fundy^ the countries bordering which—Nova Scotia, New

Brunswick, and the State of Maine—appear to be the most favourite abode

of the moose; for nowhere in the northern and western extension of the

North American forest do we find this animal so numerous as in these

districts. Absent from the islands of Prince Edward, Anticosti, and

Newfoundland, it is found on the Atlantic sea-board, and to the north of

New Brunswick, in the province of Gaspe; across the St. Lawrence, not

further to the eastward than the Saguenay, though it was met with

formerly on the Labrador as far as the river Godbout. The absence of the

moose in Newfoundland appears unaccountable; for, although a large

portion of this great island is composed of open moss-covered plateaux

and broad savannahs —favourite resorts of the cariboo or American

reindeer— yet it contains tracts of forest, principally coniferous, of

considerable extent, in which birch, willow, and swamp-maple are

sufficiently abundant to afford an ample subsistence to the former

animal, which is stated by Sir J. Richardson to ascend the rivers in the

northwest of America nearly to the Arctic Circle—as far, in fact, as the

willows grow on the banks.

Assuming that the moose

is still found in New Hampshire and Vermont, where it exists, according

to Audubon and Bachman, at long intervals, we may therefore define its

limits on the eastern coasts of North America as lying between 43° 30'

and the fiftieth parallel of latitude.

In following the lines

of limitation of the species across the continent, we perceive an easy

guide in considering its natural vegetation. As regards the general

features of the forests which the moose affects, we find them

principally characterised by the presence of the fir tribe and their

associations of damp swamps and soft open bogs, provided that they are

sufficiently removed from the region of perpetual ground-frost to allow

of the requisite growth of deciduous shrubs and trees on which the

animal subsists. The best indication, therefore, of the dispersion of

the moose through the interior of the continent is afforded by tracing

the development of the forest southwards from the northern limit of the

growth of trees.

The North American

forest has its most arctic extension in the north-west, where it is

almost altogether composed of white spruce (Abies alba), a conifer

which, when met with in far more genial latitudes, appears to prefer

bleak and exposed situations. Several species of Salix fringe the river

banks, and feeding on these we first find the moose, even on the shores

of the Arctic Sea, where Franklin states it to have been seen at the

mouth of the Mackenzie, in latitude 69°. Further to the eastward

Richardson assigns 65° as the highest limit of its range ; and in this

direction it follows the general course of the coniferous forest in its

rapid recession from the arctic circle, determined by the line of

perpetual ground-frost, which comes down on the Atlantic sea-board to

the fifty-ninth parallel, cutting off a large section of Labrador. To

the northward of this line are the treeless wastes, termed

barren-grounds, the territory of the small arctic cariboo.

The monotonous

character and paucity of species of the evergreen forest in its southern

extension continues until the valley of the Saskatchewan is reached,

where some new types of deciduous trees appear—balsam-poplar, and

maple—forming a great addition to the hitherto scanty fare of the moose.

Here, however, the forest is divided into two streams by the

north-western corner of the great prairies—the one following the slopes

of the Eocky Mountains, whilst the other edges the plains to the south

of Winipeg and the Canadian lakes. In the former district, and west of

the mountains, the Columbia river is assigned as the limit of the moose.

On the other course the animal appears to be co-occupant with the

wapiti, or prairie elk, of the numerous spurs of forest which jut out

into the plains, and of the isolated patches locally termed moose-woods.

Constantly receiving accession of species in its south-westerly

extension, the Canadian forest is fully developed at Lake Superior, and

there exhibits that pleasing admixture of deciduous trees with the

nobler conifers—the white pine and the hemlock spruce—which conduces to

its peculiarly beautiful aspect. This large tract of forest, which,

embracing the great lakes and the shores of the St. Lawrence, stretches

away to the Atlantic sea-board, and covers the provinces of New

Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward's Island, including a large

portion of the Northern States, has been termed by Dr. Cooper, in his

excellent monograph on the North American forest-trees, the Lacustrian

Province, from the number of its great lakes; it is chiefly

characterised by the predominance of evergreen coniferse. It was all at

one time plentifully occupied by the moose, which is now but just

frequent enough in its almost inaccessible retreats in the Adirondack

hills to be classed amongst the quadrupeds of the State of New York. The

range of the animal across the continent is thus indicated, and its

association with the physical features of the American forest. As before

remarked, the neighbourhood of the Bay of Fundy appears to be its

present most favoured habitat; and it seems to rejoice especially in the

low-lying, swampy woods, and innumerable lakes and river-basins of Nova

Scotia and New Brunswick.

The scientific

diagnosis of the Alcine groups (Hamilton Smith) having been detailed

already, we pass on to describe the habits of the American moose—the

result of a long period of personal observation in the localities last

mentioned. First, however, a few remarks on the specific identity of the

true elks of the two hemispheres seem as much called for at this time as

when Gilbert White, writing exactly a century ago, asks, “Please to let

me hear if my female moose” (one that he had inspected at Goodwood, and

belonging to the Duke of Richmond) “corresponds with that you saw; and

whether you still think that the American moose and European elk are the

same creature?” In reference to this interesting question, my own recent

careful observations and measurements of the Swedish elks at Sandringham

compared with living specimens of moose of the same age examined in

America, convince me of their identity; whilst the late lamented Mr.

Wheelwright, with whom I have had an interesting correspondence on the

subject, states in “Ten Years in Sweden:“ The habits, size, colour, and

form of our Swedish elk so precisely agree with those of the North

American moose in every respect, that unless some minute osteological

difference can be found to exist (as in the case of the beavers of the

two countries), I think we may fairly consider them as one and the same

animal”* The only difference of this nature that I ever heard of as

supposed to exist, consisted in a greater breadth being accredited to

the skull, at the most protuberant part of the maxillaries, in the case

of the European elk. This I find is set aside in the comparative

diagnosis at the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, in which no

grounds of distinction whatever are evidenced.

I consider that this

and the other arctic deer—the rangifers (excepting, perhaps, in the

latter instance the small barren-ground cariboo, which is probably a

distinct species)—owe any differences of colour or size, or even shape

of the antler, to local variation, influenced by the physical features

of the country they inhabit. There is more variation in the woodland

cariboo of America in i ’3 distribution across the continent than I am

able to perceive between the elks of the Old and New World. As migratory

deer, occupying the same great zoological province, almost united in its

arctic margin, we need not look for difference of species as we do in

the case of animals whose zones of existence are more remote from the

Pole, and where we find identical species replaced by typical.

The remark of an old

writer that the elk is a “melan-cholick beast, fearful to be seen,

delighting in nothing but moisture,” expresses the cautious and retiring

habits of the moose, and the partiality which it evinces for the long,

mossy swamps, where the animal treads deeply and noiselessly on a soft

cushion of sphagnum. These swamps are of frequent occurrence round the

margins of lakes, and occupy low ground everywhere. They are covered by

a rank growth of black spruce (Abies nigra), of stunted and unhealthy

appearance, their roots perpetually bathed by the chilling water which

underlies the sphagnum, and their contorted branches shaggy with usnea.

The cinnamon fern (Osmunda cinnamomea) grows luxuriantly ; and its

waving fronds, tinged orange-brown in the fall of the year, present a

pleasing contrast to the light sea-green .carpet .of. moss from which

they spring profusely.

A few swamp-maple

saplings, witlirod bushes (viburnum), and mountain-ash, occur at

intervals near the edge of the swamp, where the ground is drier, and

offer a mouthful of browse to the moose, who, however, mostly

frequenting these localities in the rutting season, seldom partake of

food. Here, accompanied by his consort, the bull remains, if

undisturbed, for weeks together ; and, if a large animal, will claim to

be the monarch of t1 e swamp, crashing with his antlers against the tree

stems should he hear a distant rival approaching, and making sudden mad

rushes through the trees that can be heard at a long distance. At

frequent intervals the moss is tom up in a large area, and the black mud

scooped out by the bull pawing with the fore-foot-found these holes he

continually resorts. The strong musky effluvia evolved by them is

exceedingly offensive, and can be perceived at a considerable distance.

They are examined with much curiosity by the Indian hunter (who is not

over particular) to ascertain the time elapsed since the animal was last

on the spot. A similar fact is noticed by Mr. Lloyd in the case of the

European elk, “grop” being the Norse term applied to such cavities found

in similar situations in the Scandinavian forest.

The rutting season

commences early in September, the horns of the male being by that time

matured and hardened. An Indian hunter has told me that he has called up

a moose in the third week of August, and found the velvet still covering

the immature horn ; however, the connexion between the cessation of

further emission of horn matter from the system owing to strangulation

of the ducts at the burr of the completed antler, with the advent of the

sexual season,, is so well established as a fact in the natural history

of the Cervinae that such an instance must be regarded as exceptional.

The first two or three days of September over, and the moose has worked

off the last ragged strip of the deciduous skin against his favourite

rubbing-posts—the stems of young hacmatack (larch) and alder bushes, and

with conscious pride of condition and strength, with clean hard antlers

and massive neck, is ready to assert his claims against all rivals. A

nobler animal does not exist in the American forest; nor, whatever may

have been asserted about his ungainliness of gait and appearance, a form

more entitled to command admiration, calculated, indeed, on first being

confronted with the forest giant, to produce a feeling of awe on the

part of the young hunter. To hear his distant crashings through the

woods, now and then drawing his horns across the brittle branches of

dead timber as if to intimidate the supposed rival, and to see the great

black mass burst forth from the dense forest and stalk majestically

towards you on the open barren, is one of the grandest sights that can

be presented to a sportsman's eyes in any quarter of the globe. His coat

now lies close, with a gloss reflecting the sun's rays like that of a

well-groomed horse. His prevailing colour, if in his prime, is jet

black, with beautiful golden-brown legs, and flanks pale fawn. The swell

of the muscle surrounding the fore-arm is developed like the biceps of a

prizefighter, and stands well out to the front. I have measured a

fore-arm of a large moose over twenty inches in circumference. The neck

is nearly as round as a barrel, and of immense thickness. The horns are

of a light yellowish white stained with chestnut patches; the tines

rather darker; and the base of the horn, with the lowest group of prongs

projecting forwards, of a dark reddish brown.

At this season the

bulls fight desperately. Backed by the immense and compact neck, the

collision of the antlers of two large rivals is heard on a still

autumnal night, like the report of a gun. If the season is young, the

palm of the horn is often pierced by the tines of the adversary, and I

have picked up broken fragments of tines where a fight has occurred.

Though at other seasons they rarely utter a sound, where moose are

plentiful they may be heard all day and night. The cows utter a

prolonged and strangely-wild call, which is imitated by the Indian

hunter through a trumpet of rolled-up birch-bark to allure the male.

The. bull emits several sounds. Travelling through the woods in quest of

a mate, he is constantly “talking,” as the Indians say, giving out a

suppressed guttural sound—quoh ! quoh! —which becomes much sharper and

more like a bellow when he hears a distant cow. Sometimes he bellows in

rapid succession; but when approaching the neighbourhood of the forest

where he has heard the call of the cow moose, and for which he makes a

bee line at first, he becomes much more cautious, speaking more slowly,

constantly stopping to listen, and often finally making a long noiseless

detour of the neighbourhood, so as to come up from the windward, by

which means he can readily detect the presence of lurking danger These

latter cautious manoeuvres on the part of the moose are, however, more

frequently exercised in districts where they are much hunted; in their

less accessible retreats the old bulls will often rush up to the spot

without hesitation. The suspicious and angry bull will often go into a

thick swamp and lay about him amongst the spruce stems right and left,

now and then making short rushes—the dead sticks flying before him with

reports like pistol shots. I have often heard a strange sound produced

by moose when “real mad,” as the Indians would say—a halfchoked sound as

if there was a stoppage in the wind-pipe, which might be expressed—hud-jup,

hud-jup ! When with his mate, his note is plaintive and coaxing—cooah,

cooah!

A veteran hunter, now

dead, well-known in Nova Scotia as Joe Cope—to be regretted as one of

the last examples of a thorough Indian, and gifted with extraordinary

faculties for the chase—thus described to me, over the camp-fire, one of

his earlier reminiscences of the woods—the subject being a moose fight.

It was a bright night

in October, and he was alone, calling, on an elevated ridge which

overlooked a great extent of forest land. “I call,” said he, “and in all

my life I never hear so many moose answer. Why, the place was bilin with

moose. By-and-by I hear two coming just from opposite ways—proper big

bulls I knew from the way they talked. They come right on, and both come

on the little hill at same time—pretty hard place, too, to climb up, so

full of rocks and windfalls. When they coming up the hill, I never hear

moose make such a shockin’ noise, roarin’, and tearin’ with their horns.

I just step behind some bushes, and lay down. They meet just at the top,

and directly they seen one another, they went to it. Well, Capten, you

wouldn’t b’lieve what a noise—just the same as if gun gone off. Well,

they ripped away, till I couldn’t stand it no longer, and I shot one of

the poor brutes; the other he didn’t seem to mind the gun one bit—no

more noise than what he been making and he thought he killed the moose ;

so I just loaded quick, and I shot him too. What fine moose them

was—both layin' together on the rocks! No moose like them now-a-days,

Capten.”

It is not long since

that an animated controversy appeared in the columns of a sporting paper

under the heading “Do stags roar?” It was decided, I believe, that such

was the case with the red-deer of the Scottish hills, by the testimony

of many sportsmen. I can testify that such is also a habit of the moose,

and many will corroborate this statement. On two occasions in the fall I

have heard the strange and, until acquainted with its origin, almost

appalling sound emitted by the moose. It is a deep, hoarse, and

prolonged bellow, more resembling a feline than a bovine roar. Once it

occurred when a moose, hitherto boldly coming up at night to the

Indians' call, had suddenly come on our tracks of the previous evening

when on our way to the calling-ground. On the other occasion I fallowed

a pair of moose for more than an hour, guided solely by the constantly

repeated roarings of the bull, which I shot in the act.

Young moose of the

second and third year are later in their season than the old bulls.

Before the end of October, when their elders have retired, though they

will generally readily answer the Indians' call from a distance, they

show great caution in approaching—stealthily hovering round, seldom

answering, and creeping along the edges of the barren or lake so as to

get to leeward of the caller, making no crashing with their horns

against the trees as do the older bulls, and always adopting the;

moose-paths. In consequence they are seldom called up.

When the moose wishes

to beat a retreat in silence, his suspicions being aroused, he can

effect the same with marvellous stealth. Not a branch is heard to snap,

and the horns are so carefully carried through the densest thickets that

I believe a porcupine or a rabbit would make more noise when alarmed.

In the fall the bull

moose, forgetting his hitherto cautious habits of moving through the

forest, seems, on the contrary, bent on making himself heard, “sounding”

(as the Indians term it) his horns against a tree with a peculiar

metallic ring. Sometimes the ear of the hunter, intently listening for

signs of advancing game, is assailed by a most tremendous clatter from

some distant swamp or burnt-wood, “just (as my Indian once aptly

expressed it) as if some one had taken and hove down a pile of old

boards.” It is the moose, defiantly sweeping his forest of tines right

and left amongst the brittle branches of the ram-pikes, as the scathed

pines, hardened by fire, are locally termed. The resemblance of the

sound of the bull when he'answers at a great distance off to the

chopping of an axe is very distinct; and even the practised ear of the

sharpest Indian is often exercised in long and’anxiously criticising the

sound before he can make up his mind from which it emanates. There are

of frequent occurrence, in districts frequented by these animals, what

are termed moose-paths — well-defined lines of travel and of

communication between their feeding grounds which, when seeking a new

browsing country, or when pursued, they invariably make for and follow.

These paths, which in some places are scarcely visible, at other times

are broad enough to afford a good line of travel to a man; they are also

used by bears and wild cats. Sometimes they connect the little mossy

bogs which often run in chains through a low-lying evergreen forest; at

others they traverse the woods round the edges of barrens, skirting

lakes and swamps. I have often observed that moose, chased from a

distance into a strange district, will at once and intuitively take to

one of these moose-paths.

With the exception of

the leaves and tendrils of the yellow pond lily (Nuphar advena), eaten

when wallowing in the lakes in summer, and an occasional bite at a tus-sack

of broad-leaved grass growing in dry bogs, the food of the moose is

solely afforded by leaves and young terminal shoots of bushes. The

following is a list of trees and shrubs from which I picked specimens,

showing the browsing of moose, on returning to camp one winter’s

afternoon. Eed maple, white birch, striped maple, swamp maple, balsam

fir, poplar, witch hazel, mountain ash. The withrod is as often eaten,

and apparently relished as a tonic bitter, as the mountain ash; but the

young poplar growing up in recently burnt lands in small groves, with

tender shoots, appears to form the most frequently sought item of diet.

In winter young spruces are often eaten, as, also, is the silver fir; in

the latter case the Indians say the animal is sick. The observant eye of

the Indian hunter can generally tell in winter, should drifting snow

cover up its tracks, the direction in which the moose has proceeded,

feeding as he travels, by the appearance of the bitten boughs; as the

incisors of the lower jaw cut into the bough, the muscular upper lip

breaks it off from the opposite side, leaving a rough projection

surmounting a clean-cut edge, by which the position of the passing

animal is indicated. The wild meadow hay stacked by the settlers back in

the woods is never touched by moose, though I have seen them eat hay

when taken young and brought up in captivity. A young one in my

possession would also graze on grass, which, vainly endeavouring to crop

by widely straddling with the forelegs he would finally drop on his

knees to eat, and thus would advance a step or two to reach further, and

in a most ludicrous manner.

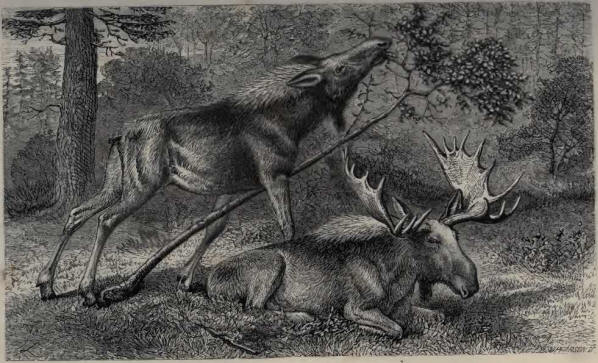

To get at the foliage

out of reach of his mouffle the animal resorts to the practice of riding

down young trees, as shown in the accompanying woodcut.

The teeth of the moose

are arranged according to the dental formula of all ruminants, though I

once saw a lower jaw containing nine perfect incisors. The crown of the

molar is deeply cleft, and the edges of the enamel surrounding the

cutting surfaces very sharp and hard as adamant—beautifully adapted to

reduce the coarse sapless branches on which it is sometimes compelled to

subsist in winter, when accumulated snows shut it out from seeking more

favourable feeding grounds. I have often heard it asserted by Indian

hunters that a large stone is to be found in the stomach of every moose.

This, of course, is a fable ; but a few years since I was given a

calculus from a mooses stomach which I had sawn in two. The concentric

rings were well defined, and were composed of radiating crystals like

needles. The nucleus was plainly a portion of a broken molar tooth which

the animal had swallowed. A short time afterwards I obtained another

bezoar taken from a moose. The rings were fewer in number than in the

preceding case, but the nucleus was a very nearly perfect and entire

molar.

MOOSE RIDING-DOWN A TREE.

The young bull moose

grows his first horn (a little dag), of a cylindrical form, in his

second summer, i.e., when one year old. Both these and the next year’s

growth, which are bifurcate, remain on the head throughout the winter

till April or May. The palmate horns of succeeding years are dropped

earlier, in January or February—a new growth commencing in April. The

full development of the horn appears to be attained when the animal is

in its seventh year.*

As a means of judging

age, no dependence is to be placed on the number of the tines, but more

upon the colour and perfect appearance of the antler. In an old moose,

past his prime, the horns have a bleached appearance, and the tines are

not fully developed round the edge of the palm. It is my impression that

when moose are much disturbed, and are not allowed to “breed” their

horns in quiet, contorted and undersized horns most frequently occur.

Double and even treble palms, folded back one layer upon the other, are

not uncommon; and sometimes an almost entire absence of palmation

occurs, in which case I have seen a pair of moose horns ascribed to the

cariboo. Structural irregularity of the antler is frequently the result

of constitutional injury. A friend in Nova Scotia, well known there as

“the Old Hunter,” recently gave me a pair of horns of most singular

appearance, the original possessor of which he had shot a few falls

previous. They were of a dead-white colour, without palmation, and with

immense and knotted burrs and long bony excrescences sprouting from the

shafts of the antlers like stalactites. The horn matter, instead of

flowing evenly over the surface, had been impeded in its course, and had

burst out at the base of the horn. The animal, an unusually large and

old bull, when shot showed evident signs of having been in the wars

during the previous season. Several of his ribs were broken, and the

carcass bore many other marks of injury. The very bones appeared

affected by disease, and were dried up and marrowless.

Even when badly

wounded, the moose is seldom known to attack a man unless too nearly

approached. There are instances, however, recorded to the contrary. An

old Indian, long since dead, called “ Old Joe Cope” (not the Joe

previously mentioned), was for years nearly bent double by a severe

beating received from the forefoot of a wounded moose which turned on

him. For safety, there being no tree near, he jammed himself in between

two large granite boulders which were near at hand. The aperture did not

extend' far enough back to enable him to get altogether out of the reach

of the infuriated bull.

Whatever may be said

about the mild eyes of the dying moose, a wounded animal, unable to get

away, assumes a very “ ugly ” expression. The little hazel eye and

constricted muscles of the mouffle speak volumes of concentrated hate.

Such scenes I have lost no time in terminating by a quick coup de grdce.

When the moose faces the hunter, licking his lips, it is a caution to

stand clear.

Portions of skeletons,

the skulls united by firmly locked antlers, are not unfrequently found

in the wilderness arena where a deadly fight has occurred, and the

unfortunate animals have thus met a lingering and terrible death, to

which may be applied the well-known lines of Byron in illustration—the

contest, indeed, being prolonged beyond the original intention :—

“Friends meet to part:

love laughs at faith;

True foes, once met, are joined till death !”

A splendid pair of

locked horns of the American moose now adorn the Museum of the Royal

College of Surgeons.

In hot weather the

moose appears much oppressed and lazy; he will scarcely stir, and a

little exertion causes him to pant and the tongue to hang out. Cold

weather, on the contrary, braces him up, and we always find that on a

frosty night and morning in the fall of the year the moose is more

inclined to travel and answer the hunters call than on a close night,

though in the height of the season. The best time for calling is on a

cold frosty morning just before sunrise, when a rime frost whitens the

barrens, and the air holds a death-like stillness, the constant hooting

of the cat-owls (Bubo Yirginianus) portending the approach of a storm.

Except in the height of

the rutting season, the great ear of the moose is ever on the alert to

detect danger ; the slightest snap of a dead bough trodden on by the

advancing hunter, and he is off in a long swinging trot for many a mile.

He readily perceives the difference of sounds occasioned by the presence

of his human foe to those produced by the animals or birds of the

forest, or by the approach of his own species. “The only way you can

fool a moose" says my Indian, “is when the drops of rain are pattering

off the trees on to the dead leaves; then he don’t know nothing.”

The presence of the

moose is so difficult to detect, except by tracks and signs of browsing,

that habitual silence and caution in walking through the forest becomes

a leading trait in the moose hunter, whose eyes are ever glancing around

through the forest. By observing this strictly, and from long habit, I

shot my last moose unexpectedly. On our road to the calling ground, a

picturesque little open bog of a hundred acres or so in the middle of a

heavily-wooded evergreen forest, we had passed through a descending

valley under tall hemlock woods on the soft mossy carpet which makes

travelling easy and grateful to the moccasined foot. Not a word had been

spoken save in cautious undertones, and debouching on the bog, we walked

up to a little pile of rocks and dead trees near the centre, where we

were to try our luck with the moose-call on the approach of evening, and

quietly deposited our loads—blankets and camp-kettle. Lighting our

pipes, we sat still for a few moments, scanning the edges of the woods.

It was perfectly calm ; not a sound except the cry of the jay or the

woodpecker’s tap. Presently the Indian, who lay in the bushes close by,

gave a little warning “hist;” and, looking up, I saw a fine moose

standing about eighty yards off, and slowly looking about him. He had

come out of the woods close to our point of exit, and we must have been

passed by him quite handy. I was capped; and in a few minutes crowds of

moose-birds had assembled to share the hunter’s feast. But for our

caution we should never have seen or heard him.

In November, the

rutting season over, the bull moose again seeks the water and recovers

his appetite : remaining, nevertheless, in poor condition throughout the

winter. He may be now seen standing listless and motionless for hours

together, and seeming to take but little notice of the approach of

danger unless his nostrils are invaded by the scent of a human being,

which will start a moose under any circumstances. About this time the

cows, young bulls, and calves congregate in small parties of three to

half a dozen, and affect open barrens and hill sides, where there is a

plentiful supply of young wood of deciduous trees, constituting what is

termed a “moose-yard.” If undisturbed they will remain on such spots,

feeding round in an area more or less limited in extent, for several

weeks; when, the supply of provender failing, they break up camp and

proceed in search of fresh ground. When the weather and state of the

snow permits, these shifts are practised throughout the winter. In

Canada, however, and in Northern New Brunswick, the moose is a far less

migratory animal than he is in Nova Scotia, owing to the great depth of

the snow; once he chooses his yard he has to remain in it, and is quite

at the mercy of the hunter who may have discovered the locality, and who

can invade his domains at any time and at his own convenience. The old

bulls become very solitary in their habits, and, indeed, seem to avoid

the society of their species, living in the roughest and most

inaccessible districts, on hill sides strewn in the wildest confusion

with bleached granite boulders, and windfalls where some forest fire has

passed over and left the land thus desolate.

In severe snow-storms

the moose seeks shelter from the blinding drift (poudre) in fir

thickets. In the yard, the animal spends the day in alternately lying

down for periods of about two hours, and rising to browse on the bushes

near at hand. About ten o’clock in the morning, and again in the

afternoon, they may generally be found feeding, or standing, chewing the

cud, with their heads listlessly drooping. At noon they always lie down

; and the Indian hunter knows well that this is the worst time of day to

approach a yard, as the animal is then keenly watching, with its

wonderful faculties of scent and hearing on the alert, for the faintest

taint or sound in the air which would intimate coming danger. I have

waited motionless for an hour at a time, knowing the herd was reposing

close at hand, and anxiously expecting a little wind to stir the

branches so as to cover my advance, which would otherwise be quite

futile. The snapping of a little twig, or the least collision of the

rifle with a branch in passing, or the crunching of the snow under the

moccasin, though you planted your footsteps with the most deliberate

caution, would suffice to start them.

The moose is not easily

alarmed, however, by distant sounds, nor does he take notice of dogs

barking, the screams of geese, or the choppings of an axe—sounds,

emanating from some settler’s farm, which are borne through the air on a

clear frosty morning to an astonishing distance in America. Indeed, I

once was lying in the bushes in full view of a magnificent bull when the

cars passed on a provincial railway at a distance of four or five miles,

and the deep discordant howl of the American engine-whistle, or rather

trumpet, woke echoes from the hill-sides far and near. Once or twice he

raised his ears and slowly turned his head to the sound, and then

quietly and meditatively resumed the process of rumination.

In April, about the

time of the sap ascending in trees, the moose horns begin to sprout, the

old pair having fallen two months previously. The latest date that I

have ever seen a bull wearing both horns was on the 29th of January. The

cylindrical dag of the moose in his second year, and the two-pronged and

still impalmate horn of the next season are, however, retained till

April. In the middle of this month the coat is shed, and for some time

the moose presents a very rugged appearance. Towards the end of May the

cow drops one or two calves (rarely three), by the margin of a lake,

often on one of the densely-wooded islands, where they are more secure

from the attacks of the black bear or of the bull moose themselves. It

has been affirmed as one of the distinctive traits of the Arctic deer

that the fawns are not spotted. Though faint, there are decided dapples

on the sides and flanks of the young moose; in the cariboo they are

quite conspicuous. In May the plague of flies commences, driving the

more migratory cariboo to the mountains and elevated lands, and inducing

the moose to pass much of his time in the lakes, where they may be

frequently seen browsing on water-lilies near the shore, or swimming

from point to point. Besides the clouds of mosquitoes and black flies (Simulium

molestum) which swarm round everything that moves in the woods, there

are too large Tabani, or breeze flies, that are always about moose, a

grey speckled fly, and one with yellow bands. The former is locally

termed moose-fly, and is very troublesome to the traveller in the woods

in summer, alighting on an exposed part, and quickly delivering a sharp

painful thrust with its lance-like proboscis. A tick (Ixodes) affects

the moose, especially in winter and early spring. The animal strives to

free itself from their irritation by striding over bushes and brambles.

The ticks may often be seen on the beds in the snow where moose have

lain down, and whence they are quickly picked up by the ever-attendant

moose birds, or Canada jays (Corvus canadensis). These vermin will

fasten on the hunter when backing his meat out of the woods. The Indian

says: “Bite all same as a piece of fire.”

So many are the Indian

tales illustrating the supposed power that the moose possesses of being

able to hide himself from his pursuers by a complete and long-sustained

submergence below the surface of the water, that one is almost inclined

to believe that the animal is gifted with an unusual faculty of

retaining the breath. I know that moose will feed upon the tendrils and

roots of the yellow pond lily by reaching for them under water. An

instance occurring in the same district in Nova Scotia that I was

hunting in, and at the same time, which was related to me, will serve as

a sample of the oft-repeated stories bearing on this point. We had

crossed a fresh moose track of that morning’s date on proceeding to our

hunting grounds on the Cumberland hills in search of cariboo. Not caring

to kill moose we left it; but shortly after the track was taken up and

followed on light new-fallen snow by a settler. Having started the

animal once or twice without getting a shot, he followed its track to

the edge of a little round pond in the woods whence he could not find an

exit of the trail. Sitting down to smoke his pipe before giving it up to

return, his gun left against a tree at some distance, he was astonished

to see the animal’s head appear above the surface in the middle of the

pond. On jumping up, the moose quickly made for the opposite shore, and,

emerging from the water, regained the shelter of the forest ere he could

get round in time for a shot. The Indians have a tradition that the

moose originally came from the sea, and that in times of great

persecution, some half-century since, when no moose tracks could be

found in the Nova Scotian woods, they resorted to the salt water, and

left for other lands. An old hunter, now dead, told me he was present

when his father shot the first moose that had been seen since their

return; that great were the rejoicings of the Indians on the occasion,

and that two were shot on the beach by a settler who had seen them

swimming for shore from open water in the Bay of Fundy. I can vouch for

an instance of a moose, when hunted, taking to the sea and swimming off

to an island considerably over a mile from the mainland. Such tales are

evidently intimately connected with the powers of the animal in the

water, in which, as has been previously stated, it passes much of its

existence during the hot weather. A similar hunter’s story to the one

related above is quoted by Mr. Gosse in the “Canadian Naturalist.”

In conclusion, it is

with regret that the conviction must be expressed that this noble

quadruped, at no very distant period, is destined to pass away from the

list of the existing mammalia. The animal has fulfilled its mission ; it

has afforded food and clothing to the primitive races who hunted the

all-pervading fir forests of Central Europe and Asia to subarctic

latitudes, whilst, until very recently, its flesh, with that of the

cariboo, formed the sole subsistence of the Micmacs and other tribes

living in the eastern woodlands of North America. To these the beef of

civilisation—wenju-teeamwee, or French moose-meat, as the Indian calls

it—but ill and scantily supplies the place of their once abundant

venison. It has enabled the early and adventurous settler to push back

from the coast and open up new clearings in the depths of the forest.

With a barrel of flour and a little tea, rafted up the lakes or drawn on

sleds over the snow to his rude log hut, he was satisfied to leave the

rest to the providence of nature ; and the moose, the salmon, and the

trout, with the annual prolific harvest of wild berries, contributed

amply to the few wants of the fathers of many a rising settlement. With

but few and exceptional instances, the moose or the elk has not become

subservient to man as a beast of burden as has the reindeer; neither is

it, like the latter, still called upon to afford subsistence to nomade

tribes of savages who live entirely apart from civilisation. Being an

inhabitant of more temperate regions, it is brought more constantly

within the influences of the permanent neighbourhood of man, and thus,

whilst its extinction is threatened by slaughter, a sure but certain

alteration is being effected in the physical features of its native

forest regions. The often purposeless destruction of woods by the axe,

and the constant devastation of large areas of forest by fires, too

frequently the result of carelessness, are reducing the moisture of the

American wilderness, removing the sponge-like carpet of mosses by which

the water was retained, and rendering the latter a less fitting abode

for the moose. Destruction of his domains and constant disturbance are

undoubtedly slowly dwarfing the species. We no longer hear of examples

of the monster moose of the old times of which Indian tradition still

speaks, and when the well-authenticated diminution in the size of the

red deer of the Scottish hills is remembered, an appearance of less

exaggeration than is usually attributed to them marks the tales of the

early American voyageurs concerning the moose.

When the Russian

aurochs and the musk-sheep of Arctic America shall have disappeared, it

is to be feared that Cervus Alces of the Old and New Worlds, his fir

forests levelled, his favourite swamps drained, and unable to exist

continuously in the broad glare and radiation of a barren country, will

follow, to be regretted as one of the noblest and most important mammals

of a past age; his bones will be dug from peat-bogs by a future

generation of naturalists, and prized as are now those of the Great Auk

of the islands of the North Atlantic, or of the Struthiones of New

Zealand, which have perished within the ken of the scientific record of

modern natural history. |