|

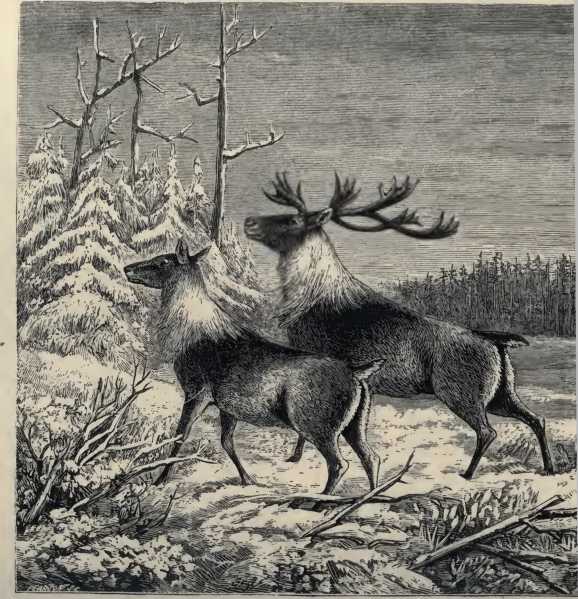

The cariboo of the

British provinces is only to be approached by the sportsman with the

assistance of a regular Indian hunter. In old times the Indians

possessed and practised the art of calling the buck in September, as

they now do the bull moose, the call-note being a short hoarse bellow;

this art however is lost, and at the present day the animal is shot by

stalking or “creeping” as it is locally termed, that is, advancing

stealthily and in the footsteps of the Indian, bearing in mind the

hopelessness of success should sound, sight or scent give warning of

approaching danger. As with the moose, the latter faculty seems to

impress the cariboo most with a feeling of alarm, which is evinced at an

almost incredible distance from the object, and fully accounted for, as

a general fact, by the size of the nasal cavity, and the development of

the cartilage of the septum. As the cariboo generally travels and feeds

down wind, the wonderful tact of the Indian is indispensable in a forest

country, where the game cannot be sighted from a distance as on the

fjelds of Scandinavia, or Scottish hills. Of course, however, on the

plateaux of Newfoundland and Labrador, and on the large cariboo-plains

of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, less Indian craft is brought into

play, and the sport becomes assimilated to that of deer-stalking.

It is almost hopeless

to attempt an explanation of the Indian’s art of hunting in the woods —

stalking an invisible quarry ever on the watch and constantly on the

move, through an ever-varying succession of swamps, burnt country, or

thick forest. A review of all the shifts and expedients practised in

creeping, from the first finding of recent tracks to the exciting moment

when the Indian whispers “Quite fresh; put on cap,” would be

impracticable. I confess that like many other young hunters or like the

conceited blundering settlers, who are for ever cruising through the

woods, and doing little else (save by a chance shot) than scaring the

country, I once fondly hoped to be able to master the art, and to hunt

on my own account. Fifteen years5 experience has undeceived me, and

compels me to acknowledge the superiority of the red man in all matters

relating to the art of “venerie ” in the American woodlands.

When brought up to the

game in the forest, there is also some difficulty in realising the

presence of the cariboo. At all times of the year its colour is so

similar to the pervading hues of the woods, that the animal, when in

repose, is exceedingly difficult of detection: in winter, especially,

when standing amongst the snow-dappled stems of mixed spruce and birch

woods, they are so hard to see, and their light gray hue renders the

judging of distance and aim so uncertain, that many escape the hunters

bullet at distances, and under circumstances, which should otherwise

admit of no excuse for a miss.

And now let us proceed

to our hunting ground.

The first light snow

had just fallen after two or three piercingly cold and frosty days

towards the close of November, when our party, consisting of us two and

our attendant Indian, the faithful John Williams, (than whom a more

artful hunter or more agreeable companion in camp never stepped in

mocassin) arrived at the little town of Windsor, at the head of the

basin of Minas, whence embarking in a small schooner, we were to cross

to the opposite side to hunt the cariboo in the neighbourhood of

Parsboro’. The distance across was but a matter of thirty miles or so,

and with light hearts we stepped on board, and stowed our camping

apparatus, bags of provisions, blankets and rifles in the hold of the

“Jack Easy,” when presently the rapidly ebbing tide bore us swiftly down

the course of the Avon into the dark-coloured waters of the arm of the

Bay of Fundy.

The first part of the

voyage was pleasant enough; a light though freshening breeze from the

eastward filled the sails ; and we swept on with the surging tide of red

mud and water past the great dark headland of Blomidon with its

snow-streaked furrows and crown of evergreen forest, enjoying both our

pipes and the prospect, and recalling the various interesting traditions

of this famed location of the old Acadians whose memory has been so

beautifully perpetuated by Longfellow. But on leaving the cape' and

standing across the open bay, we soon encountered a rougher state of

affairs. The dark murky clouds now commenced discharging a heavy fall of

damp snow, which froze upon everything as soon as it fell, rendering the

process of reefing, which had become necessary from the increasing

breeze, very difficult of accomplishment. The sheets were coated with a

film of ice, and frozen stiffly in the blocks, and the deck became so

wet and slippery that we were glad to retire below into the close little

cabin. We had embarked at sunset, as the tide did not suit until then,

and not even a small schooner of the dimensions of the “Jack Easy” can

leave the Windsor river until the impetuous tide of this curious bay

sweeps up, and, rising to the height of forty feet, bears up all the

craft around the wharves from their soft repose in the red mud. It was

now dark, and the storm increased; the wind, being against tide, raised

a tumultuous sea. Presently there were two or three vivid flashes of

lightning, followed by increased violence of the wind and dense driving

hail, and the little schooner lay heavily over. We, the passengers, were

huddled together in a cabin so small that it was with difficulty we

could keep our knees from touching the stove round which we crowded.

Everyone smoked, of course, and the strong black tobacco of the settlers

vied with the rushes of smoke, driven by the wind down the stove-pipe,

in producing in the den a state of atmosphere threatening speedy

suffocation, and we were glad to grope our way into the dark hold and

seek an asylum amongst the tubs, barrels, and potato sacks which were

rolling about in great uneasiness. At last it was over: a quieter state

of affairs, a great deal of stamping and slipping on deck, and, finally,

the long rattle of the cable, told us we were anchored off Parsboro’—a

fact which was corroborated by the captain opening the hatch and

lowering himself amongst us, one mass of ice and snow; his clothes

rattled and grated as he moved as though they were constructed of board.

There was no shore bed for our aching bones that night; the tide did not

suit to reach the wharf, the village was a mile and a half away, and the

night was still stormy, so we again sought soft spots pn the inexorable

benches around the stove in our den.

“Hurrah, John! ” said

I, as we followed the Indian up the ladder, and emerged into the cold

morning air; “here’s snow enough in all conscience—just the thing for

our hunting—step out now for the village, and let’s try and scare up a

breakfast somewhere.”

It was still snowing

heavily, and the country looked as wintry as it could do even in North

America. In the distance appeared the little white wooden houses and

church of the village, and behind them rose up the great grey form of

the Cobequid Hills. The brisk walk through the snow soon recalled warmth

to our benumbed frames, and, the village inn once reached, it was not

long ere the ample breakfast of ham and eggs and potatoes, pickles and

cheese, cold squash-pie, and strong black tea, was arranged before us.

“Will the Indian make

out with you, gents?” asked the exceedingly pretty innkeeper’s daughter.

We all glanced at John, who laughed as he anticipated our reply.

“Oh, of course, yes; we

are all on the same footing this morning, we guess. Come on, John, sit

up and give us some ham.”

The landlord—who

affected to be a bit of a sportsman, of course—told us there were lots

of cariboo back in the hills, and some moose, which he reckoned would be

the great object of our hunting; for, in this part of Nova Scotia, the

moose has only recently made his appearance, and the settlers look upon

him as far nobler game than the common cariboo. Presently a sleigh with

a stout pony appeared for us at the door, and, loading it with our

baggage, we left to the tune of a peal of merry bells which the pony

carried attached to different parts of the harness.

Our road lay through a

valley, skirted by the lofty wooded slopes of the Cobequids. These hills

are the great stronghold of the cariboo, and his last resort in Nova

Scotia; they extend through the isthmus which connects the province with

that of New Brunswick, and are covered with large hard-wood forests of

sugar and white maple, birch, and beech. On their broad tops and sides

the cariboo has an unbroken range of more than a hundred miles, and

their eastern spurs, descending into a flat district of dense fir

forests, with numerous chains of lakes, offer secure retreats in the

breeding season.

The country was new to

us, and its features novel: the evergreen forest, so characteristic of

the greater portion of the province, here almost entirely gave way to

hard-woods, narrow lines of hemlock or spruce springing up from some

deep gorge on the mountain side, here and there showing their dark

summits, and coursing like veins through the great rolling sea of

maples. The latter part of the storm had been unaccompanied by wind, and

the snow lay in heavy masses on the trees, giving the forest a most

beautiful aspect; it covered every branch and every twig, and was

thickly spattered against the stems, and all the complicated tracery of

the denuded branches was brought to notice, even in the deepest

recesses, by the white pencil of the snow-storm. In the fir forest the

effect of newly-fallen snow is very fine also, but the very masses which

cover the broad and retentive branches of the evergreens and clog the

younger trees until they seem like solid cones of snow, hinder and choke

the view; whereas in these lofty hard-woods, under which grows nothing

but slender saplings, a most extensive glimpse of their furthest depths

is obtained, and thousands of delicate little ramifications, before

unnoticed, now stand out in bold relief in the grey gloom of the

distance. And then, when the storm has passed by, and that beautiful

blue tint of a wintry sky, coursed by light fleecy scud, succeeds the

heavily laden cloud, how exquisitely the scene lights up! what a soft

warm tint is thrown upon the light-coloured bark of the maples and

birches, and upon the prominent dottings and lines of snow which mark

their forms, and how lovely is that light purple shade which continually

crosses the road, marking the shadows! As the sun increases in warmth,

or a passing gust of wind courses through the trees, avalanches of snow

fall in sparkling spray, and the new snow glitters in myriads of little

scintillations, so that the eye becomes pained by the intensity of

brilliancy pervading the face of nature.

We stopped the sleigh

opposite a group of Indian bark wigwams, which stood a short distance

from the road; the noise of voices and curling wreaths of smoke from

their tops proved them to be occupied, and, as we required a second

Indian hunter, particularly one who was well acquainted with the

neighbourhood, we followed the track which led up to them, and entered

the largest. The head of the family, who sat upon a spread cariboo-skin

of gigantic proportions, was one of the finest old Indians I ever

saw—one of the last living models of a race now so changed in physical

and moral development that it may be fairly said to be extinct. An old

man of nearly eighty winters was this aged chief, yet erect, and with

little to mark his age save the grizzly hue pervading the long hair

which streamed over his broad shoulders, and half concealed the faded

epaulettes of red scalloped cloth and bead-work. A necklace of beads

hung round his neck, and, suspended from it, a silver crucifix lay on

his bare expansive chest. His voice, as he welcomed us, and beckoned us

to the post of honour opposite to the fire and furthest from the door,

though soft and melodious, was deep-toned and most impressive. Williams,

our Indian, greeted and was greeted enthusiastically; he had found an

old friend, the protector of his youth, in whose hunting camps he had

learnt all his science; the old squaw, too, was his aunt, whom he had

not seen for many years.

The chief was engaged

in dressing fox-skins: he had shot no less than twenty-three within the

week or two preceding, and whilst we were in the camp a couple of

traders arrived, and treated with him for the purchase of the whole,

offering two dollars a-piece for the red foxes, and five or six for the

silver or cross-fox, of which there were three very good specimens in

the camp. The skin of the fox is used for sleigh robes, caps, and

trimmings. The valuable black fox is occasionally shot or trapped by the

Indians, and the skin sold, according to condition and season, from ten,

even as high as twenty pounds. The coat of a good specimen of the black

fox in winter is of a beautiful jet black colour, the hair very long,

soft, and glossy; and, as the animal runs past you in the sunshine on

the pure snow, and a puff of wind ruffles the long hair, it gleams like

burnished silver. It appears that the whole of the black fox-skins are

exported to Russia, and are there worn by the nobility round the neck,

or as collars for their cloaks; the nose is fastened by a clasp to the

top of the tail, the rest of which hangs down in front.

The old man told us of

the curious method he used in obtaining his fox-skins. He would go off

alone into the moonlit forest, to the edge of some little barren, which

the foxes often cross, or hunt round its edges at night.

Here he would lie down

and wait patiently until the dark form of a fox appeared in the open. A

little shrill squeak, produced by the lips applied to the thumbs of the

closed hands, and the fox would at once gallop up with the utmost

boldness, and meet his fate through the Indian's gun.

He regretted that he

was too old to accompany us himself, but advised us to take a young

Indian who was at that time encamped on the ground to which we were

proceeding; and we left the old man's camp, and resumed our trudge on

the main road, after seeing him make a successful bargain for his

fox-skins.

That afternoon we had

reached our destination; the last few miles of the road had been more

and more wild and uneven, and at last we drew up before a tenement and

its outbuildings which stood on the brow of a hill and overlooked a wide

extent of country. It was the house of the last settler, and those great

undulating forests before us were to be the arena of our sport. Buckling

on the loads, we dismissed the sleigh, and turned at once into their

depths.

We had not far to carry

our loads, for the Indian camp was erected on a hard-wood hill, within

reach of the sounds of the last settler's clearing. This we found

afterwards to be a great comfort, as we often called on him for the loan

of his sleigh and trusty yoke of oxen, and drew large supplies of fine

mealy potatoes from his cellar; great luxuries they are, too, and

valuable additions to the camp fare, though they often have to be

omitted, when the distance of the hunting country from the settler's

house precludes any extra weight in the apportioned loads.

Noel Bonus, the owner

of the camp, was at home, just returned from his hunting, for an early

dinner, and to him we applied direct to act as our landlord and hunter.

I never saw a dirtier or more starved-looking Indian; selfishness and

cunning were plainly stamped on his tawny face, which was topped by the

shaggiest mass of long black hair conceivable ; he seemed irresolute for

some moments as to whether he should admit us, and take the dollar per

diem and his share of the meat, or whether he should continue to hunt on

his own account, and leave us to shift for ourselves.

We did not urge the

point, for we had a first-rate hunter, John Williams, with us, and

though he did not know the country, he would soon master that difficulty

; and, as to a camp, .we had all the requisite appliances for quickly

setting up on our own account. This became gradually evident to Master

Noel, who at last motioned us to take off our loads and come in—a

proceeding which we politely declined doing until a thorough renovation

and cleansing had taken place, and the dirty bedding of dried shrivelled

fir-boughs, strewed with bones and bits of hide and hoof, had been swept

out and replaced by fresh. It was a capital camp, strongly built, and

quite rain-proof, standing on a well-timbered hard-wood hill, the stems

of the smaller trees affording an unlimited supply of fuel; a small

spring trickled down the hill-side close by.

As we unpacked our

bundles to get at the ammunition (for we were determined to have a

cruise around before dark), Noel told us that he had, early that same

morning, missed a cariboo not more than a mile from camp. We started in

different directions, I with Noel, and my comrade with the older hunter.

It was a bright, frosty afternoon, very calm, and the beautiful woods

still retained their oppressive loads of heavy snow, rendering it very

difficult to see game between the thickly-growing evergreens. Noel first

followed a line of marten traps of his own setting—little dead-falls

occurring every fifty yards or so in a line through the woods for nearly

a mile. There was nothing in them, though I saw several tracks of marten

on the snow. Fox-tracks, and those of the little American hare, commonly

called the rabbit, on which the fox preys, were exceedingly numerous,

and there was a fair sprinkling of the other tracks which are usually

found on the snow in the forest, such as lucifee or wild cat, porcupine,

partridge, and squirrel. Presently Noel gave a satisfactory grunt, and

pointed to the surface of the snow ahead, which was evidently broken by

the track of some large animal.

“Fresh track, caliboo,

thees mornm,” whispered he, as we came up to the trail of two cariboo,

which had gone down wind, and in the direction of some large barrens

which Noel said lay about a mile away. We might yet have a chance by

daylight, so on we went pretty briskly, though cautiously. Noel pointed

out several times small pieces which had been bitten off the lichens

growing on the stems of the hard-wood trees, of which they had taken a

passing mouthful. Who but an Indian could have detected such minute

evidences of their actions? There was no doubt but that they were making

for the barrens, or they would have stopped at these tempting morsels

longer, and here and there perhaps deviated from the line of march.

Probably they knew of companions, and were going to a rendezvous, .or

preferred the reindeer moss amongst the rocks on the barren.

The tall forest of

maples and birches was presently succeeded by a dense growth of

evergreens, which became more and more stunted as we approached the

barren, and here and there opened out into moist swampy bogs, into which

we sank ankle-deep at every step : finally, we brushed through the thick

shrubbery, drenched with the snow dislodged plentifully over us en

passant, and stood on the edge of a most extensive barren.

Such a scene of

desolation is seldom witnessed, except in these great burnt and denuded

wastes of the North American forest. As far as the eye could reach was a

wild undulating wilderness of rocks and stumps ; a deep indigo-coloured

hill showed the limits of the barren, and where the heavy fir forest

again resumed1 its sway. It appeared to be some ten miles or so in

length, and to slope from us in a gentle declivity towards the westward.

The average breadth might be four or five miles. Little thickets and

groves of wood dotted it in all directions ; sometimes a clump of

spruce, against which the white stem of the birch stood out in bold

relief; or, at others, a patch of ghost-like rampikes; whilst the brooks

in the valleys were marked by fringing thickets of alder.

Boulders of rock and

fallen trees were strewed over the whole surface of the country in the

wildest confusion; and the dark, snow-laden sky cast a shade over the

scene, investing it with the most forbidding and gloomy-appearance

imaginable.

Carefully scanning the

surrounding country, and not perceiving any signs of the game, we

proceeded on their tracks, which were soon increased in number by those

of three other cariboo, joining in from the southward. They led us

through some dense thickets, where we had to proceed with the greatest

caution, there being no wind, and on account of the uncertainty of the

moment or place where we might come upon them. I was getting tired of

the whole proceeding, when, as we were crossing an open spot amongst

rocks and sparsely-growing spruce clumps of about our own height, I saw

Noel, who was ahead, suddenly stop, with his hand held back, and slowly

subside in the snow, which proceedings of course I followed, without

question as to the cause or necessity.

“What is it, Noel?”

said I, gaining his side by slowly worming along in the snow, with

difficulty keeping the muzzle of my rifle above the surface.

“Caliboo lying down,”

he replied. “You no see them now? Better fire, I think.”

I could not for my life

see the cariboo, although I looked along the barrel of his gun, which he

pointed for me in the right direction. They are most difficult animals

to recognise unless moving, being so exceedingly similar in colour to

the rocks and general features of the barren, that only the eye of the

Indian can readily detect them when lying down. Noel had at once seen

the herd; and here was 1, unable to perceive them amongst the rocks and

bushes, though pointed to the exact spot, and knowing that they were

little more than one hundred yards distant. At last I saw the flapping

of one of their ears, and gradually the whole contour of the recumbent

animal nearest to me became evident.

I now did a very

foolish thing, and was determined to have my shot at the nearest cariboo,

lying down. The animal was in a hollow, deeply bedded in the snow, so

that very little of the back could be seen, and I aimed at the lowest

part visible above the snow. I pulled—a spirt of snow showed that the

dazzling surface had deceived me, and the bullet ricochetted harmlessly

over the back of the cariboo.

Up they jumped, five of

them, apparently rising from all directions around us, and, after a

brief stare, made off in long graceful bounds. I at once seized the old

musket which the Indian carried, but the hammer descended on harmless

copper—the cap was useless. “This is bad,” thought I ; for I hate

missing the first shot on a hunting excursion, particularly with game to

which one is not accustomed, as there is still more fear of becoming

unsteady, and missing, on the next chance presenting itself; and I

watched the cariboo with longing eyes, and a feeling of great

disappointment, as they settled down into a long, swinging trot, and

wound in file over the barren, towards the line of forest on the north

side. As for the hungry-looking Indian, I did not know whether to have

at him on the score of his excessive ugliness, or for not carrying

better caps for his gun.

“Get back to camp,

Noel, as quick as you can,” said I; “it will be dark in half an hour.

Why didn't you put up the cariboo on their legs for me before I fired?”

“Gentleman just please

himself,” replied the Indian. “You did very foolish; nice lot of caliboo,

them. Maybe other gentleman get shot, though.”

“Oh, it’s the fresh

steak for supper you are thinking of,” thought I to myself, feeling as

discontented and generally uncharitable as possible. “I hope sincerely

they have not, though;” and I trudged after the Indian homewards in an

unenviable mood. Fortunately there was an old road leading across the

barren towards the settlements, and, presently striking it, we obtained

easy walking. A couple of hours, the latter part by moonlight, brought

us to our camp. No smoke issued from the top, and everything was as we

left it. The others had not returned, and we made up a fire and cooked

the meal we so much needed.

“I was almost afraid

you were lost, John,” said I, as the blanket which covered the entrance

was withdrawn by the returning hunter and my companion, very late in the

evening; “any sport?”

“Never fear,” replied

Williams, laughing, as he lugged in a great sack of potatoes, and

produced a bottle of new milk, and some loaves of home-made bread;

“here’s our game. We just had first-rate dinner at settler’s; good old

man, that old Harrison.”

They, too, had fired at

cariboo, and wounded a young one slightly. It had led them a race of

some miles, and finally, having joined a fresh herd, had escaped through

the confusion of tracks. However, we retired to our repose on the soft

bed of fir-boughs that night, quite satisfied and hopeful. We were in a

fine country, evidently full of game, and we looked forward to our

future shots with confidence, satisfied, from what we had seen, that the

cariboo was one of the finest deer, for sport, in the wide world.

What a hearty meal is

breakfast in the winter camp of a party of hunters in the American

backwoods! The pure air which enters freely and circulates round the

camp, heated by the great log fire in the centre, round which we range

ourselves for sleep, regardless of the cold without (except, perhaps, on

some especially severe passage of cold, when actual roasting on one side

will scarcely keep the opposite from freezing), conduce to sound and

healthy repose, and a feeling of wonderful freshness and activity on

awakening and throwing off the blanket or buffalo robe early in the

morning.

The Indians are already

up, one cleaning the guns, or “fixing” a moccasin, whilst the other is

holding the long-handled frying-pan, filled with spluttering slices of

bacon, over the glowing embers. Their toilet amounts to nil; when well

they always look clean, though they seldom wash; though they never use a

comb their long, shining, raven-black hair is always smooth and

unruffled. We, with our combs, brushes and towels, step out into the

cold morning air and betake ourselves to the little brook for ten

minutes or so, and then return with appetites whetted either for venison

or the flesh of pig, washed down by potations of strong black tea, which

has simmered by the embers, perhaps, for the last halfhour.

“John,” said I, as we

reclined on our blankets at breakfast the morning after our unsuccessful

cariboo hunt, “did you hear the wild geese passing over to the southward

last night? I heard their loud ‘honk! honk! several times, and the

whistling of their wings as they flew over the camp. It froze pretty

sharp, too; the trees cracked loudly in the forest.”

“I hear ’urn, sure

enough,” replied the Indian. “Guess winter set in pretty hard up to

nor’rerd. I got notion some of us have luck to-day, capten. I dreamin'

very hard last night. When I dream so always sure sign we have luck next

day. I think it will be you ; me and the other gentleman must go back

and try to get the wounded caliboo calf.”

“Very well, then: Noel

hunts with me again to-day,” said I, looking at the younger Indian, who

nodded assent and drew on his moccasins. “Come on, Noel; put a biscuit

in your pocket, and let us be off for the barrens.” It was a lovely

morning when we left the camp; not a breath of wind, and the sun shone

through the trees, lighting with extraordinary brilliancy the sparkling

snow which had been sprinkled during the night with rime frost. All

nature seemed to rejoice at the warming influence of the sun's rays. The

squirrel raced up the stems with more than usual activity, and the

little chickadee birds darted about amongst the spruce boughs in merry

troops, dislodging showers of snow, and continuously uttering the

cheerful cry which has given them their local sobriquet. The tapping of

the woodpecker resounded through the calm forest, and the harsh warning

note of the blue jay gave notice of our approach to his comrades and the

forest denizens in general. Here and there a ruffed grouse started with

boisterous flight from our path, as we disturbed his meditations on some

sunlit stump; and, soon after entering the barren, a red fox jumped from

the warm side of a clump of bushes where he had been basking, and made

oft’ at racing speed—a far handsomer animal than our English Reynard,

whose fur is quite dingy compared with the bright orange-red coat of the

American.

“Ah! I don't like to

see this" said Noel, pointing out some large tracks in the snow; “these

brutes been huntin' about here some time. You see that track?— that

wolf-track—two of them; them tracks we seen yesterday, when we thought

dogs were chasing moose, them was wolf-tracks."

The day before we had

noticed the tracks of what we chen thought had been dogs chasing a young

calf-moose. At one place—a very deep, swampy bog—they had nearly run

into him, for, on the snow, we saw hair which they had pulled from his

flanks. It seems that about ten years ago wolves made their appearance

in this province in considerable numbers from New Brunswick, and their

nightly howlings caused the farmers to look closely after the safety of

their stock and folds for some time in certain settlements. They are,

however, now rarely heard of.

We had not been long on

the barren ere we came on last night's tracks of five cariboo, and we at

once commenced creeping in earnest. Presently we found their beds,

deeply sunk in the snow, the surface quite soft, and evidently just

quitted. Their tracks showed that they had, on rising, commenced feeding

along very leisurely on the mosses of the barren; to get at which they

had scraped away the snow with their broad hoofs. It was now a capital

morning for creeping, as the surface of the snow on the barren was quite

soft, loosened by the power of the sun. Now we enter a little bog, with

scattering clumps of spruce growing from its wet, mossy surface ; at

every step we sink ankle deep into the yielding moss, and the chilling

snow-water soaks into our feet. We look anxiously ahead for the game,

but they have crossed the bog ; nor are they on the next, which we can

scan from our present position. They must be in that dark patch of woods

just beyond, which skirts the barren, for we have followed them up to

its northern edge. What a pity! for the snow under the shade of the

forest is still hard and crusted, and its crunching sound, under the

pressure of our moccasins, step we ever so lightly, cannot escape the

ear of the cariboo. Yes, they have entered the wood, and just as we

prepare to follow them, and gently open our way through the outlying

thickets, I hear a light snap of a bough within, which sends my heart

nearly to my mouth. Another step, and Noel at once points to game, and I

see some shadowy forms moving among the trees, at about fifty yards'

distance. Now is the time; an instant more and we should be discovered,

and the cariboo bound off scatheless, with electric speed. The quick

crack of my rifle is followed by the roar of the Indian’s gun (which I

afterwards ascertained contained two balls, and about four drachms of

powder), and the branches loudly crash in front as the herd starts in

headlong flight.

There was blood on the

snow, as we came up to the spot whence they had fled: a broad trail of

it led from the spot where the animal I had fired at had been standing.

Presently I saw the cariboo ahead, going very slowly, and making round

for the barren again, having left the herd. The poor creature’s doom was

sealed; for, as we emerged from the woods, we saw it lying down, and a

fawn, which had accompanied it, made quickly off on seeing us approach.

I would have spared the latter, but the Indian brought it down at once

by a good shot at eighty yards. Mine proved to be a very fine doe, with

a dark glossy skin, and in excellent condition.

“Plenty fresh meat in

camp now,” says Noel, who really looked as if he could have eaten the

whole cariboo then and there. He did roast a good junk of it as soon as

he could get a fire alight, and the fellow had brought out some salt in

a piece of paper in case of an emergency like the present. Whilst Noel

was making up the meat with the assistance of the little axe and

hunting-knife which are invariably suspended from the hunter’s belt, I

lighted my pipe and heaped on the dead logs, which lay •everywhere under

the surface of the snow, until we had a roaring fire that would have

roasted a cariboo whole with great ease and dispatch. I never saw fatter

meat than that of the largest cariboo when the hide was removed ; the

whole saddle was snow-white with fat, which covered the meat to the

depth of an inch and a half. Having stacked the quarters in a compact

pile, and deeply covered them with a coating of snow, we started for

home, leaving the offal for the Canada jays and crows; the former were

exceedingly impudent, hopping about within a few yards of us, and

screaming most impatiently for our departure. Noel of course carried a

goodly load of the meat, including many delicate morsels for our camp

frying-pan.

Numerous droves of

cariboo had crossed the barren since the morning, and, as we were on our

way, we saw a small drove of four passing across at a distance of about

500 yards from us. They appeared scared, walking very

ON THE BARRENS.

briskly, and

occasionally breaking into a trot. Most probably they had been started

by the rest of the party in the woods to the southward. One of them was

of a very light colour—the lightest, I think, I ever saw— being of a

pale, tawny hue all over; the others were, as usual, dull grey,

variegated with dingy white. Sport must have fallen to the lot of anyone

who had remained concealed in some central thicket on the barren this

afternoon, from the number that must have passed at different times, as

appeared by their tracks. Though it was still early in December we had

only as yet seen one buck who retained his horns; the does still wore

theirs. The one I had just killed had an exceedingly neat little pair,

which, but for her untimely end, would have graced her until the ensuing

March.

On return to camp, I

found that my friend had not been so fortunate; they had not been able

to discover the wounded cariboo, and had started two herds without

getting a shot. This was owing to the frozen state of the snow in the

woods. We had determined to exchange Indians next morning; but, in

consequence of his not yet having had success, I agreed to start again

with the second hunter, Noel, and leave to my friend the undisturbed

possession of the barrens, my direction being the Buctegun plains, which

were distant some eight miles or so to the westward. Noel, of course,

ate until he could eat no more that night—in fact, I never saw such

gluttony as was displayed by this Indian whenever he got a chance. The

settler s wife had told me, a few days since, that he made a common

practice of going into one house after another along the road, and at

each representing himself as starving. His appearance not generally

belying his assertion, he has succeeded in getting a dinner at each of

four different places on the same day. “But,” she said, “they found him

out; and he finds it rather hard to get asked out, or rather in, to

dinner now-a-days.” On one occasion, on returning with me to camp, after

an unsuccessful morning, a good deal before the usual time for dining,

he complained of a severe attack of indigestion, and adopted, as an

unfailing remedy, a hearty meal of fried pork—the fattest he could pick

out of the bag. He expressed himself to the effect that lubrication was

the best remedy for such complaints.

The owls hooted most

dismally in the forest that night —a sure sign, as Williams said, of an

approaching storm; and, as the sky looked threatening all the latter

part of the day, we retired to sleep, trusting to see a fall of fresh

snow in the morning, which was much wanted, to obliterate the old

tracks, and soften the surface of the crust.

Fresh falls of snow are

necessary to continue and ensure sport in the winter hunting-camp,

especially in the earlier part of the season. A few bright days thaw the

surface so that the night-frost produces a disagreeable crust, which

crunches and roars under the moccasin most unmusically; and then, unless

the forest trees are shaken by little short of a gale, you may give up

all idea of getting within shot of game. Day after day is often thus

spent listlessly in camp; the same calm, frosty weather continuing to

prevent sport, and the evil of the crust on the snow gradually becoming

worse; the Indians shaking their heads at the proposition to hunt and

uselessly disturb the country, and betaking themselves to cutting

axe-handles, mending their moccasins, or constructing a hand-sled

perhaps, whilst you lazily fall back amongst the blankets, and snooze

away far into the bright morning, till the noon-day sun strikes down on

your face through the aperture in the top of the camp. Then you are told

by the dusky cook and steward of the camp that the “pork's giving out"

or the “sweetening is getting short," and all things remind you that

“it's hard times and no fresh meat, and all for want of a nice little

fall of snow. However, there lies a great ball of a thing, all covered

with quills, like a hedgehog, in the cook's corner, and the cook

recommends that a “bilin" of soup should be instituted; so Master

Porcupine is scraped, and skinned, and chopped, and, with an odd bone or

two which turns up from the larder, a little rice, and lots of sliced

onions, he is converted into a broth, and another day in the woods is

cleared by the pork thereby saved. At last, when the bitter reflection

of having to return from the woods empty-handed presents itself to you

some morning on awakening, the joyous flakes are seen gently falling

through the top of the camp, and hissing as they meet the embers of the

fire. “Now's your time," says the party all round, and the camp is all

bustle and animation—such tying on of moccasins, and buckling on of

ammunition-belts, and knives, and axes; not forgetting to provide for

the mid-day refreshment, by filling of flasks, and stowing away of

biscuits and lumps of cheese. Presently the wind rises, and the storm

thickens; the new covering of snow seems to draw out the frost from the

old crusted surface, and the moccasin now steps noiselessly in the

tracks of the game. That day, or on the next, there is no need of

porcupine soup, for huge steaks hang from the camp-poles, and a rich and

savoury odour pervades the camp, whilst the hissing frying-pan tops the

logs.

The want of a fresh

fall of snow had thus interrupted our sports in the Parsboro’ country

for some days, when the welcome flakes at last came down one wild stormy

night, and covered the forest and barren with a clean mantle of three or

four inches, obliterating the old tracks, and softening the crust so

that it again became practicable to stalk the wary cariboo. Many times

had we started small herds on the barren, and in the greenwoods, without

sighting them; the first token of their proximity, and of their having

taken alarm, being the crashing of the branches which they breasted in

flight.

It was a beautiful

hunting morning on which, after the new fall of the previous night, we

trudged along the forest-path leading from our camp to the barrens, and

made sure of shots during the day, for the change of wind, and the

storm, would cause a movement among the deer. A mile or so from camp the

snow was ploughed up by a multitude of fresh tracks; a herd of cariboo

had just crossed it; there could not have been less than thirty of them,

all going south from the barrens. We at once struck into the woods after

them, and followed for about an hour, when the herd divided into two

streams. One of these we followed, the tracks every moment becoming

fresher, until, on passing through a dense alder thicket which grew over

water, treacherously covered with raised ice, the ice gave way with a

crash, and we at the same moment heard the game start. We rushed on as

fast as possible, for they had not seen or winded us, and might possibly

think the noise proceeded merely from the ice falling in, ,as it often

does when suspended over water and laden with snow. Presently the tracks

showed they were walking, and on entering a thick covert of young

spruces, whose lower branches, thickly covered with snow, prevented our

seeing far ahead, the Indian said, “There—fire!” and a bounding form or

two flashed through an opening in the bush with such rapidity that we

could scarcely say that we had seen them. Our barrels were levelled and

discharged, but, as might be expected, without effect. The deer had been

lying down, and had seen our legs under the lower branches before the

Indian was aware of their presence.

Williams said, “I 'most

afraid we couldn't get shot. Caliboo very hard to creep when shiftin'

their ground : don't stop and feed much, and when they lie down they

watchin' all the time, and then up agen 'most directly. I know them

caliboo makin' for some big barrens, five or six mile away.''

We then turned back to

the northward, and, recrossing the road, made for the barrens where my

dead cariboo were lying. The place was marked by the great pile of snow

which we had shovelled over them, and by the skins suspended on a

rampike hard by; no wild animals had disturbed the meat, though great

numbers of moose-birds and jays were screaming around, apparently

distressed that the fresh snow had covered up their little pickings in

the shape of offal, which had been left around. Here we sat down on a

log, after clearing off the snow, to eat our biscuit and broach the

flasks (for we had trudged many miles since breakfast, and the sun was

past the south)—the Indian, always restless, and perhaps anxious to take

a survey of the country unimpeded by followers, going off towards the

greenwoods, distant a few hundred yards, munching as he went.

“A capital fellow is

old John,” said I to my comrade. “I'll bet you what you like he comes

back with some news. I’ve often seen him go off in this manner whilst

you are eating, or resting, or smoking, and uncertain what to do, and

come back in half an hour or so, apparently having learnt more of the

whereabouts of the game than he had when in your company during the

whole morning’s hunt.”

We were not detained

very long, however—indeed, had hardly finished the biscuit—when, on

looking towards the edge of the forest, which he had entered a few

minutes previously, we saw John emerge, and make his way back to us with

unusual celerity; and, seeing there was game afoot, we picked up the

guns and advanced to meet him.

“Come on,” says John,

“just see three or four of 'em walking quietly along inside the

woods—didn’t start ’em, I guess. Be easy, now; lots of time.” And off we

go after John, as quietly as he would have us, and soon find the track

of the cariboo. John leads rapidly forward, bending almost double to get

a glimpse of them through the branches ahead ; but no, they have left

the woods, and taken to the open again, and we follow into a swamp

thickly sprinkled with little fir trees of about our own height. The bog

is very wet, having never frozen, and we sink up to our knees in the

swamp, through the wet surface-snow, withdrawing our feet and legs at

each step, with a noise like drawing a cork. It is hard work getting

along, and already we are rather out of breath; but we must keep on, for

cariboo are smart walkers, and until they come to a place where they

have an inclination to loiter and browse, are apt to lead one a dance

for many hours, particularly when they have taken a notion to shift

their country. Ha! there goes one of them; his black muzzle and dusky

back just showing above the bushes at the further end of the swamp—and

another, and another. “Bang” goes a barrel a-piece from each of us, and

the nearest one falters, either wounded or confused, as they sometimes

become by the firing. He is again making off, and passing an opening;

the other guns floundering forward in hopes of getting nearer, when,

steadying myself, and taking good aim, he falls instantaneously to my

second barrel. John, with a yell, rushes up, and getting astride of the

struggling beast, quickly terminates his existence with his long

hunting-knife. It was a fine doe cariboo, with a very dark hide, and in

fair condition. The others having never begun fairly within shot, we

were satisfied, and after the usual process returned to camp, our path

being enlivened by the bright rays of a lovely moon. We all agreed that

no finer sport could be obtained amongst the larger game than cariboo-shooting.

This deer is so wary, such a constant and fast traveller, and so quick

in getting up and bounding out of range when started in the woods, that

an aim as rapid and true as in cock-shooting is required; and, when he

is down, every pound of the meat repays for backing it out of the woods,

being, in my opinion, far finer wild meat than any other venison I have

tasted.

The next day I walked

with the other Indian (Noel) to the Buctouktdegun plains, some ten miles

distant from our camp—great plains of miles and miles in extent, covered

with little islands of dwarf spruces of a few feet in height. This is a

great place of resort for cariboo; they come out from the forest on to

the plains on fine sunny mornings, and scrape up the snow to get at the

moss. Having passed a night in a lumberer’s camp, we proceeded next

morning to the plains, which the Indian would scan from a tall spruce,

to see if there were game on them; and having bagged my cariboo, and

given part of it to the lumberers, who seemed very thankful, we made up

the hind quarters and hide into two loads, and arrived in camp the same

evening. My companion, whose shots I had heard the day previous, had had

excellent sport on the barrens, having killed four cariboo; and the

following day I killed a magnificent buck, which weighed nearly four

hundred-weight, after a long chase of six miles through the green woods

from the spot where I had first wounded him, the Indian (it was

Williams) keeping on his track, though it had passed through multitudes

of others, with unerring perseverance.

Then comes the hauling

out the meat. Old H-, the last settler, whose house is not far from our

camp, is sent for, and contracts for the job, and one fine morning his

voice, as he urges on his patient bullocks towards the camp, and the

grating of the sled upon the snow, are heard as we sit at breakfast.

Leaving his team munching an armful of hay in the path, he comes to the

camp door, and, pushing aside the blanket which covers the entrance,

accosts us,—

“Morning, gents. Ah!

Ingines, how d’ye make out— most ready to start? We’ve got a tidy spell

to go for the cariboo by all accounts, and my team aint noways what you

may call strong. However, I suppose we must manage it somehow, and

accommodate a gentleman like you appear to be”

“All right, my good

man, we are ready; and John and Noel will go ahead and haul out the

cariboo from the barren to the road;” and off we go, a merry party,

following the ox sled, whilst the old settler shouts unceasingly to his

cattle, “Haw! Bright—Gee! Diamond; what are ye ’bout there, ye lazy

beasts?” and the great strong animals go steadily forward, occasionally

bringing their broad foreheads in violent contact with a tree; but

proceeding, on being set right, with perfect unconcern, till we come to

the edge of the barren. Here the Indians had already hauled out two of

the cariboo by straps fastened to the horns, drawing the carcases easily

over the surface of the snow, and in a couple of hours we were again en

route for home, with everything packed up, guns in case, and nine

cariboo as trophies.

The frozen carcases

were pitched down into the hold of the little schooner, the same one

which had brought us across before; and in a few hours, with a fresh

breeze following us, we grated safely through the floating field of ice

which nearly blocked up the basin of Minas, and landed at Windsor, Nova

Scotia, and so to Halifax. |