|

On the 12th of March we

left Portsmouth for Plymouth, getting away from England finally on the

26th of the same month. During our passage out we met with several

accidents, which had the effect of delaying our arrival at our

destination for a considerable while, but which would be of little if

any interest to the reader. I may say shortly, then, that after

springing a leak in the Bay of Biscay, which compelled us to run in to

Lisbon, and breaking the screw-shaft a few days later, which left us for

some time without the aid of steam, we reached Bio Janeiro on the 25th

of May. We were detained here until the necessary repairs could be

effected, leaving it on the 9th of July. After meeting with nothing more

remarkable than a heavy gale off the Rivei; Plate, we entered the

Straits of Magellan on the 29th of July, and were detained there by

stress of weather for three weeks. On the 19th of August, however, we

passed out, and picking up a fair wind, reached Valparaiso on the 28th

of the same month. Starting thence on the 8th of September, we arrived,

after a pleasant passage, at Honolulu, Sandwich Islands, on the 16th of

October.

Although our stay at Honolulu was short, opportunity was given us to see

a great deal of the place and neighbourhood. Of late years, from being a

mere Indian village, it has become an important harbour for the ships

engaged in whale-fishing in the North Pacific. This is conducted

principally by vessels of the United States; and the white population of

Honolulu, therefore, is almost exclusively American. It is no secret, I

believe, that great efforts have been made by these settlers and their

Government for the annexation of the Sandwich Islands. In this they have

been baffled by their own unpopularity, and the strenuous

counter-exertions of the advisers of King Kame-hame-ha II., who have

been hitherto selected from the few English and Scotch residents in his

dominions. Kame-hame-ha, indeed, is essentially English in his habits,

dress, the fashion of his residence, and in his system of government,

which is enlightened and progressive. He has for his chief adviser a

very worthy old Scotch gentleman, by name Wylie; and his queen is the

daughter of an Irish settler in his dominions, and a very pleasant,

sensible woman.

Personally this monarch with the unpronounceable name is a

well-educated, gentlemanly man, who speaks English and French fluently,

and who has travelled a good deal both in Europe and America. It is said

that, when travelling in the States, he was not allowed at some place to

join the table d’hote, on account of his having black blood in his

veins, although he is really little, if at all, darker than a sunburnt

Englishman. Considering the many temptations incidental to his position,

and that his royal father was, I believe, almost a savage, Kame-hame-ha

II. may, in extenuation of his evil habits, offer pleas which have

before now excused the much more glaring excesses of enlightened

European monarchs and gentlemen. Unfortunately, King Kame-hame-ha is not

without many social faults; but though addicted, as there is no doubt he

is, to the pleasures of the table and conviviality generally, I believe

him to be anything but the drunkard and debauchee that I have heard him

called by some of his guests and critics.

Something—much, I think—should be conceded to the influences of his

childhood, and the difficulties of his maturer years. Son of a father

who, although wild and uncultivated as any North American Indian, had

seen enough of the advantages of education to desire them for his son,

he was put under competent masters, and afterwards sent to travel; thus

European habits, tastes, and manners were engrafted upon his semi-wild

nature. Of course these placed a barrier for ever between him and his

native subjects. He could no longer associate with them, and he

naturally joined the only society that was in the least suited to

him—viz., that of the American residents. Among these he had offered him

the choice of the American missionaries or merchants. The former, though

most exemplary and useful men, who have done a great deal of good among

the natives and the crews of the whaling ships, led lives far too

austere and ascetic to please the young monarch. The others, however

ineligible associates for a young man with strong passions, had at least

the merit of being pleasant companions. It is therefore, perhaps, little

to be wondered at that he should have preferred their society.

The King may frequently be met at the houses of his foreign subjects, at

their balls, dinners, and supper parties; and although always treated

with a certain amount of deference, and placed in the seat of honour, it

sounds strange to hear a man say across the table, “King, a glass of

wine with you!” or, “Do you feel like brandy-and-water this morning,

King?” I believe in his heart, Kame-hame-ha is thoroughly sick of his

present life; but the task of reformation is no easy one, and he has no

one to help him in it. He has lately expressed a great desire that

England should assist him socially and morally, as she has done

politically. He has long desired the establishment of the Church of

England in his dominions. So anxious is he for this, that he has

postponed the christening of his child in the hope of being able to have

that ceremony performed by an English bishop. He endeavoured to enlist

the sympathies and obtain the services of the Bishop of British Columbia

for this purpose; and failing that, Queen Emma actually at one time

contemplated making the voyage to England with her child, with the

double object of having him baptised by episcopal hands, and of inducing

our gracious Queen to become his sponsor.

During our stay at

Honolulu, the King’s brother, Prince Lot, acceded to our request to show

us a native dance, or Hula-hula, such as we had read of in the voyages

of the old explorers. It was common enough in the days of Cook and

Vancouver, but has gone out of fashion since quadrilles and champagne

have been introduced at Honolulu. Probably the missionaries have had

much to do with its abolition, and indeed no objection they may

entertain to it can be considered unreasonable.

A Hula is a festive entertainment which I find it somewhat difficult to

describe. The one we saw was held near a village some ten or twelve

miles from Honolulu, to which we all rode on the horses which are so

good and plentiful in this island. Some 200 or 300 natives were present.

Almost all the dancers were women dressed in a costume somewhat similar

to that of our European ballet-girl. The music was played by some

half-dozen men seated on their haunches at the far end of the room

behind the dancers, who sang a wild chant, accompanied by perpetual

rapping on small drums. Some of the dancers carried large shields made

of feathers bound up with very bright-coloured cloth—a gourd, fixed on

to the centre at the back, forming the handle. The gourds were filled

with pebbles, and were rattled with extraordinary vehemence as the

dancers became excited. The contortions into which they put themselves

are quite beyond my powers of description. There was, however, a certain

wild grace in all their movements, and they kept admirable time with

each other and to the music. The chants have a peculiar significance to

the islanders, and many of their traditions are, I believe, bound up iu

them. Dinner was provided before the dancing commenced, which latter was

kept up with wonderful spirit all through the night. We were entertained

exclusively on native dishes, spread on the ground in native fashion:

knives and forks, &c., with ale and wine, forming the only foreign

portion of the arrangements.

Among the dishes was chowdar—a preparation of fish stewed with

suet-pudding, well known in America—and several things cooked in a

manner peculiar, I believe, to the Pacific Islands, by being wrapped up

in palm-leaves and baked between two hot stones. This is called

“loo-ou.” Dog used to be a common article of diet in the Sandwich

Islands, but of late years it has gone out of fashion. But for a very

natural repugnance, that it might be difficult to master, these dogs

would be by no means disagreeable; for, as with frogs in France, they

are devoted early in life to culinary purposes, and are fattened as pigs

might be, and not allowed—as pigs often are—to eat flesh.

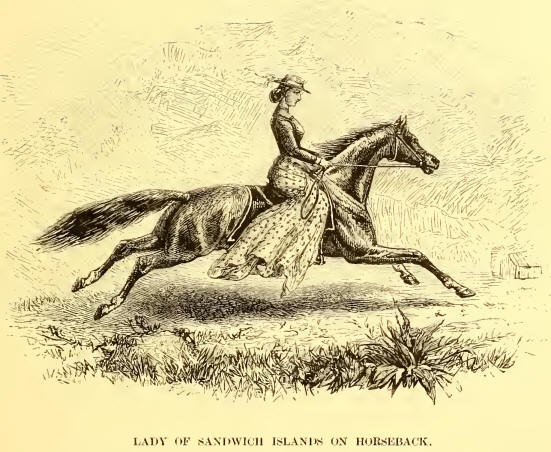

The Sandwich Islands horses are very good, and wonderfully cheap. Many

have been exported to Vancouver Island with great success. The women are

bold equestrians : the use of the side-saddle is entirely unknown to

them, and they ride en cavalier on the Spanish saddle, which is made by

the natives everywhere in the Pacific. They ride most pluckily, and by

no means ungracefully, wearing a roll of bright yellow or red cloth,

sufficiently long to reach below the feet; this is fastened at the

waist, and wrapped loosely round the lower limbs, so as to form a sort

of loose trowsers.

Before leaving Honolulu, I may mention the Sailors’ Home, to which the

residents liberally subscribe, from the king downwards. There is

accommodation in it for nearly eighty men, and in the season when the

whalers crowd into the harbour they manage to accommodate many more. The

sailors are charged five dollars a week, and the officers—for whom a

separate table is kept—eight dollars, for their hoard and lodging.

23rd October, 1857.—Sailed from Honolulu this day, and on the 9th of

November entered the Strait of Juan de Fuca, which divides Vancouver

Island from the mainland of the American continent. In making the Strait

of Fuca, should the weather be clear enough for the navigator to see the

Flattery Bocks, he will at once know his position. These rocks, which

lie twelve miles south of Cape Flattery and extend some three miles off

shore, have a considerable elevation, and are sufficiently peculiar in

their aspect to be readily identified. In fair weather the entrance to

the Strait is plainly visible from them; and as they are passed, the

lighthouse upon Tatoosh, off Cape Flattery, opens in view.

All high northern latitudes are peculiarly liable to sudden changes of

weather, and in entering the Strait of Fuca all the knowledge and

experience of which the navigator is master will often be called into

requisition. The currents at the entrance of the Strait are not very

strong, varying from one to four knots; but their set is uncertain,

although when once fairly in the Strait the flood-stream will be found

to run in, and the ebb out. Captain Trivett, of the Hudson Bay Company's

service, who has made many voyages to Victoria, recommends that the

south coast of Vancouver Island should be avoided in light winds, as,

should it fall calm, the ship would be at the mercy of a heavy swell

that almost always sets in on the shore, and renders it at times

difficult to get off the coast. My subsequent experience, however, would

incline me, on the contrary, to hug the island-coast, as, although the

swell sets on to the island, the current appears almost invariably to

set to the southward. This southerly set nearly caused the loss of

H.M.S. ‘Hecate,’ in 1861, when, during a fog, she was drifted on to the

rocks inside Tatoosh Island, when we thought we were still well north of

it, Captain Stamp, an old seaman who, living at Barclay Sound, is in the

habit frequently of taking small schooners to and from Victoria, also

told me that he almost always experienced a southerly set at the

entrance of the Straits.

Off the shore of Vancouver Island a large bank, some fifteen miles in

breadth, extends the whole length of the island. It is, therefore,

advisable, as Captain Trivett in another place remarks, to be to the

northward rather than the southward in making the Strait. The edge of

this bank has been very accurately defined by the soundings of H.M.S.

‘Hecate,’ which have since been published; and as the depth of water

changes suddenly from 100 or 200 fathoms to no more than 40 or 50, the

soundings will serve as a capital guide for the approach.

The breadth of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, at its entrance between Cape

Flattery, its southern point upon American territory, and Bonilla Point

in Vancouver Island, is thirteen miles. It narrows soon, however, to

eleven miles, carrying this breadth in an east and north-east direction

some fifty miles to the Race Islands. The coasts are remarkably free

from danger, and may, as a rule, be approached closely. Upon either side

there are several convenient anchorages, which I shall shortly describe,

and which may be taken advantage of by vessels inward or outward bound.

They are well lighted, too, by both the countries interested in their

navigation; although, in this respect, the United States may be said to

carry off the palm. They have a small staff of officers whose duty it is

to attend to the lighthouses on the coast; and until the recent home

exigencies of the United States, a steamer, the ‘Shubrick,’ was

especially detailed for this service.

To return, however, to a description of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Upon

the northern side, from the shore of the island, densely-wooded hills

rise gradually to a considerable height; while on the southern, or

American shore, the rugged outline of the Olympian range of snow-clad

mountains, varying in elevation from, four to seven thousand feet, and

in breaks of which peeps of beautiful country may be seen, extend for

many miles. As the Strait is ascended the tides and currents, which at

its junction with the Pacific are of comparatively little strength,

become embarrassing, and often dangerous, to the navigator. In the

neighbourhood of the Race Islands, where the Strait takes au

east-north-east direction and meets the first rush of the waters of the

Gulf of Georgia, which have been pent-up and harassed by the labyrinth

of islands choking its southern entrance, the tidal irregularities

become so great and perplexing as to baffle all attempts at framing laws

calculated to guide the mariner. Fortunately, the course of the winds

can be ascertained with greater accuracy. At all seasons they blow up

and down the Strait of Fuca. During the summer the prevailing breezes

from north-west or south-west take a westerly direction within the

Strait; while the south-east gales of winter blow fairly out. The

mariner, however, running out of the Strait with a south-east gale, must

be prepared for a shift to the southward immediately he opens Cape

Flattery. This generally occurs, and it is of the first importance to be

ready for it; as, of course, the southerly wind catching a ship

unprepared drives her on to the dead lee-shore of the island, off which

it is no easy job to work. Upon her last voyage home the Hudson Bay

Company’s bark ‘Princess Royal,’ under the command of the Captain

Trivett I have before alluded to, was placed in great jeopardy for a

whole night from this cause.

At the Race Islands the Strait may be said to terminate, as it there

opens out into a large expanse of water, which forms a playground for

the tides and currents, hitherto pent up among the islands in the

comparatively narrow limits of the Gulf of Georgia, to frolic in.

Between Port San Juan, which is the first anchorage on the north side of

the Strait just inside the entrance, and the Pace Islands two good

anchorages occur. Sooke Inlet, the more westward of these, lies some

nine miles from the Pace Islands, and forms a splendid basin a mile and

a half square, and perfectly land-locked. The entrance, however, is so

narrow and tortuous, as to make Sooke Harbour of little practical value.

Some farms have, however, been established there, and what land there is

in its neighbourhood available for cultivation has been found to be good

and fertile.

Becher Bay lies between Sooke and the Race Islands, some four miles from

the latter. The depth of water at its entrance varies from twenty to

fifty fathoms, with a rocky and irregular bottom; and it cannot be

recommended as an anchorage, being too open to winds from the south and

west.

On the south side of the Strait is Neah Bay, four miles east-north-east

from Tatoosh Island, offering a safe and convenient anchorage to vessels

meeting south-west or south-east gales at the entrance of the Strait.

Indeed, it is very fairly sheltered from all but north-west winds, and

if threatened by them a vessel will generally be able to run out of the

bay inside the adjacent island of Wyadda, which is protected on the

north-east side. It was in Neah Bay, however, that the Hudson Bay

Company’s brig ‘Una’ was lost in 1857. She had come down from Queen

Charlotte Island, whither she had been sent to examine into some

reported gold discoveries, and was lying here when a heavy north-west

wind set in. Most of the crew were on shore at the Indian village, and

the ‘Una’ was anchored in deep water. The anchor could not be weighed,

and before they could get sail on ready for cutting the cable, she had

drifted so much that, when they tried to run through between the island

and the main, they grounded mi the point. The brig was totally lost, but

the crew were saved and treated kindly by the Indians, who muster here

in large numbers, owing to the quantity of cod, halibut, and other fish,

upon the bank which I have before referred to as running out from the

shore of the island. This fishery will no doubt, at some future time,

prove a source of considerable profit to the colony. It was for some

time doubted by the Governor and ^ others, whether the true cod was to

be caught upon this bank; but some years later, when we were here with

the ‘ Hecate,’ we settled this in the affirmative beyond a doubt. The

halibut runs here to an enormous size; it is a large flat fish, and I

have seen specimens caught that were six or seven feet long, by three or

four feet wide and six or eight inches thick. Fish of this size are very

coarse; but a small halibut is good eating. The Indians catch them with

the hook, their lines being made usually of the fibres of the

cypress-tree, or of the long kelp which abounds in these waters. They

now very generally use hooks purchased of the Hudson Bay Company, but

the native implement made of wood backed with bone may still be seen.

The canoes of these fishermen may always be met with off the entrance of

the Strait, tossing about in the chopping sea, with a coil of some fifty

or sixty fathoms of line wound round their bows. Their method of killing

large fish is particularly ingenious; they carry in their canoes a

number of bags of seal-skin made air-tight, to each of which is attached

a small harpoon barbed with iron, fishbone, or shell. A short line

connects the harpoon with the bag, and the handle being withdrawn after

the fish is struck he is allowed to play it out. He is often strong

enough to carry one or more of the seal-skin bags under the water, but

in time he comes to the surface, and is harpooned again and again, until

worn out he is towed to the shore.

Between Neah Bay and Admiralty Inlet, there are several anchorages more

or less to be recommended. The rugged coast is quite unfit, however, for

settlement; although behind the rocks that line the shore lies much rich

and fertile land, which, however, can only be reached from Admiralty

Inlet and Puget Sound.

Eight miles north of the Race Islands is the harbour of Esquimalt, and

three miles northward of that lies Victoria, the capital of Vancouver

Island, and the present seat of government for both that colony and

British Columbia. As a harbour, Esquimalt is by far the best in the

southern part of the island, or mainland. It offers a safe anchorage for

ships of any size, and although the entrance is perhaps somewhat narrow

for a large vessel to beat in or out of with a dead foul wind, it may

usually be entered easily and freely. It is moreover admirably adapted

to become a maritime stronghold, and might be made almost impregnable.

Its average depth is from five to seven fathoms, and in Constance Cove,

on the right-hand side as the harbour is entered, there is room for as

large a number of ships as we are ever likely to have in these waters to

take refuge in if necessary. As yet the want of fresh water in the

summer time is felt as an inconvenience ; but there are several large

lakes a little up the country, at a level considerably above that of the

harbour, and from them, when the resources of the colony are developed,

water can easily be brought down to the ships.

Each new admiral that is appointed to the North Pacific station appears

to be more and more impressed with the evident value and importance of

Esquimalt as a naval station. It is to be regretted, indeed, that more

land in the neighbourhood of the harbour has not been reserved by the

Government, and that steps were not long ago taken to develop its

resources. Had, for instance, a floating dock been built here in 1858,

it would by this time have more than paid for its construction; and we

should not be dependent, as we are now, upon the American dock at Mare

Island, San Francisco, for the repair of our ships of war. During the

four years of my service on this station, such a dock would have been

used on five occasions by Her Majesty’s ships, and at least a dozen

times by merchant-vessels, who, as it was, were put to great

inconvenience and even danger. For instance, when H.M.S. ‘Hecate’ ran

ashore in the autumn of 1861, we were a fortnight at Esquimalt patching

her up, before we ventured to take her to San Francisco, whither after

all we had to be convoyed by another man-of-war. This occurred too, as

it may be remembered, at a time when war with the United States seemed

imminent. Had it broken out, the ‘ Hecate ’ must have been trapped, and

the services of a powerful steamer would have been lost to the country.

Esquimalt has seen, and is still likely to see, many startling changes.

I found it altered very much from the time when as a midshipman, I first

made its acquaintance in 1849. In that year, when we spent some weeks in

Esquimalt Harbour on board H.M.S. ‘Inconstant,’ there was not a house to

be seen on its shores; we used to fire shot and shell as we liked about

the harbour, and might send parties ashore and cut as much wood as we

needed Without the least chance of interruption. Now, as we entered, I

wTas surprised to catch sight of a row of respectable, well-kept

buildings on the southeast point of the harbour’s mouth, with pleasant

gardens in front of them, from which a party of the crew of the

‘Satellite,’ who had been expecting us for some time, received us with a

round of hearty cheers. This was, we found, a Naval Hospital erected in

1854, when we were at war with Russia, to receive the wounded from

Petropaulovski, and since that time continued in use. Opposite the

hospital, our attention was directed to a very comfortable and, standing

where it did, a rather imposing residence, which was the house of

Mr. Cameron, Chief Justice of Vancouver Island, and in which I have

since spent many a pleasant hour. At the head of Constance Cove, at the

east end of the harbour, might be seen through the trees the buildings

of Constance farm, in the occupation of the Puget Sound Company; and as

we held on beyond the hospital, we came in view of the site of the

present town of Esquimalt, whose growth is of a more recent date than

that of which I am now writing.

Nor were other signs of the already growing importance of Esquimalt

wanting. It must be remembered that as yet gold, although known by some

to exist both upon the island and mainland, had attracted no notice; but

the colony was growing slowly yet surely without its stimulating aid.

Further up the harbour stood another building, named Thetis Cottage, and

at the north entrance of Constance Cove the new bailiff of the Puget

Sound Company was building a house. So, everywhere ashore, there were

changes and improvement visible. Nine years back, we had to scramble

from the ship’s boat on to the most convenient rock: now Jones’s

landing-place received us; and in the stead of forcing a path over the

rocks and through the bush to the Victoria Inlet, whence, if a native

should happen to be lounging about in the Indian village of the Songhies,

and should see us or hear our shouts and bring a canoe over, we might

hope to reach Victoria, a broad carriage-road, not of the best, perhaps,

and a serviceable bridge, were found connecting Esquimalt Harbour with

Victoria.

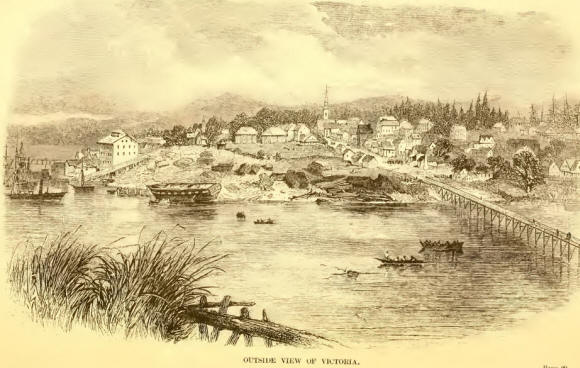

Victoria, too, was altering for the better, though slowly. The Hudson

Bay Company’s fort was still the most imposing building in the town, and

its officers the chief people there; but it had grown into a more

important station of the great Fur Company than of yore, and Mr.

Finlayson, whom we had left chief in command nine years before, we now

found Mr. Douglas’s lieutenant.

As the capital of the island, Victoria undoubtedly owes its pre-eminence

to Mr. Douglas, the present governor. As far back as 1843, when it was

considered desirable by the Company to establish a station in the

island, Victoria had been selected by him for that purpose; and later,

when the Oregon boundary question was settled, and the mouth of the

River Columbia, on which Fort Vancouver, the principal station of the

Company in Western America, stood, fell into the hands of the United

States, it was to Victoria that their head-quarters were transferred by

Mr. Douglas, who was then, and had been for some time, their chief agent

in the countries west of the Rocky Mountains. Mr. Douglas was guided in

his selection of Victoria simply by its possessing qualities which met

the requirements of the Company he represented. No one ever dreamt then

of the mineral wealth of the valleys that sloped from the Rocky

Mountains to the sea; or that in a few years cities (I should say,

perhaps, their promise) would spring up upon shores almost unknown to

the civilised world. But, long before the present rush of immigrants to

these regions, Victoria, as a port, had been virtually superseded by the

adjacent harbour of Esquimalt. The entrance to Victoria is narrow,

shoal, and intricate; and with certain -winds a heavy sea sets on the

coast, which renders the anchorage outside unsafe, while vessels of

burden cannot run inside for shelter unless at or near high water.

Vessels drawing 14 or 15 feet may, under ordinary circumstances, enter

at high water, and ships drawing 17 feet have done so, although only at

the top of spring-tides. But it is necessary always to take a pilot, and

the channel is so confined and tortuous that a long ship has

considerable difficulty in getting in. With every care, a large

proportion of vessels entering the port run aground. No doubt steps

might be taken to improve the harbour of Victoria, but it is highly

problematical whether it can ever be made a safe and convenient port of

entry for vessels even of moderate tonnage at all times of the tide and

weather. Under the most favourable circumstances, accidents happen

constantly. Last year, and again this spring, the 'Princess Royal,’ a

vessel of but 600 tons’ burden, which goes from London to Vancouver

Island every year, in the service of the Hudson Bay Company, grounded in

entering Victoria, although she was commanded by a very able man,

thoroughly acquainted with the place, and was towed at the time by a

steamer which plied in and out of the harbour two or throe times at

least every week. Nor when she was brought into the harbour was there

sufficient depth of water to allow her to get alongside the wharf, and

her cargo had to be discharged into lighters. Under these circumstances,

therefore, although Victoria is, no doubt, quite well adapted for the

vessels trading up the Fraser River, and the many small craft that will

be required among the islands and ports of the coast, ships of larger

tonnage mud always prefer Esquimalt. I cannot imagine any sensible

master of an ocean ship endeavouring to wriggle his vessel into Victoria

with the larger and safer harbour of Esquimalt handy.

Very possibly, could the future have been foreseen, Victoria would not

have been selected as the chief commercial port of Vancouver Island. But

the selection has been made, the town is built or building, the commerce

already attracted. The fact must be regarded as accomplished beyond the

possibility of change ; and the only thing that can now be done is to

connect it with the harbour of Esquimalt, towards which .task the

natural formation of the country lends itself admirably.

In the way of this, however, stand several obstacles, and chief among

them, perhaps, is the jealousy of the landholders of Victoria, who,

believing that the elevation of Esquimalt into the harbour of the colony

would lower the value of their property, have persistently opposed such

a project. Nor have the landholders of Esquimalt been altogether free

from blame. Irritated by the opposition of Victoria, and convinced that

in the end their demands must be conceded, they have placed a value upon

their land which is quite exorbitant. Many of the merchants of Victoria

would, I believe, long-ago have been glad to transfer their wharves to

Esquimalt, could they have obtained the necessary land at anything like

a fair price.

Some efforts had,

however, been made to connect the two places. As I have before said, in

1849 the country between them was impassable, and the only communication

possible was by creeping round by the shore and crossing the head of the

inlet in a canoe; but now we found a broad road carried from Victoria to

the Naval Hospital, passing through what has since become the site of

Esquimalt town, with branch ways to several important points of the

harbour. At that time this road fulfilled its purpose moderately well;

but later, when the rush to British Columbia commenced, it broke down

miserably, and it was, in the autumn of 1861, when I left, a disgrace to

the colony. In the winter it was practically almost useless, and the

waggons had to fake to the grass by the side, with what result may

easily be imagined; and when the mails were expected, the express-men

and waggon-drivers had to go over the ground the day before and patch it

up sufficiently to enable them to get to Victoria at all.

Very few words need be given to the description of Victoria. Reaching it

by the road just mentioned, the traveller passes the Hospital, supported

by voluntary contributions, and first established by the Rev. E. Cridge,

who was the Hudson Bay Company’s chaplain at Victoria for some years,

and did much good in many unobtrusive ways before the arrival of the

present bishop. Beyond, situated upon a point of land that juts out

between the first and second bridges, has since been built a foundry,

about' which, in the winter season, may generally be seen miners busy

building flat-bottomed boats, raising the gunwales of old canoes, and in

other ways making preparations for crossing the Gulf of Georgia and

ascending the Fraser River early in the spring. Further on, across the

first bridge, the road ascends a little hill, on the summit of which

lies the Indian village of the Songhies, once the sole inhabitants of

this place. The close contiguity of these Indians to Victoria is

seriously inconvenient, and various plans for removing them to a

distance have been discussed both in and out of the colonial

legislature. In consequence of their intercourse with the

whites—chiefly, of course, for evil—this tribe has become the most

degraded in the whole island, having lost what few virtues the savage in

his natural state possesses, and contracted the worst vices of the

settlers. It is scarcely possible to walk along the road by which their

village lies without stumbling upon half-a-dozen or more, lying

dead-drunk upon the ground; and it is no uncommon thing at night to

hear a ball whizz past your head, fired, not at the traveller, but from

a hut on one side of the road to one on the other in some drunken

squabble. Altogether, what with the drunkenness and the gambling—for

Indians are great gamblers, and numbers may be seen squatted on their

haunches by the roadside playing for whatever they have earned or

stolen—this village of the Songhies presents one of the most squalid

pictures of dirt and misery it is possible to conceive. To the right of

these, and stretching fiir along the northern side of the harbour, are

the tents of the tribes who come down several hundred miles from the

northernmost part of our West American possessions to barter furs, buy

whisky, and see the white men.

The Company’s fort, long the chief feature of the place, is situated on

the north-east skip of the harbour. Upon my first visit to Victoria in

1849, a small dairy at the head of James Bay was the only building

standing outside the fort pickets, which are now demolished. But shortly

after, upon Mr. Douglas’s arrival, he built himself a house on the south

side of James Bay; and Mr. Work, another chief factor of the Company,

arriving a little later, erected another in Bock Bay, above the bridge.

These formed the nucleus of a little group of buildings, which rose

about and between them so slowly that even in 1857 there was but one

small wharf on the harbour’s edge. Still, the least experienced eye

could see the capabilities of the site of Victoria for a town, and that

it was capable, should the occasion ever arise, of springing into

importance as Melbourne or San Francisco had done. As it was, the place

was very pleasant, and society— as it is generally in a young

colony—frank and agreeable. No ceremony was known in those pleasant

times. All the half-dozen houses that made up the town were open to us.

In fine weather, riding-parties of the gentlemen and ladies of the place

were formed, and we returned generally to a high tea, or tea-dinner, at

Mr. Douglas’s or Mr. Work’s, winding up the pleasant evening with dance

and song. We thought nothing then of starting off to Victoria in

sea-boots, carrying others in our pockets, just to enjoy a pleasant

evening by a good log-fire. And we cared as little for the weary tramp

homeward to Esquimalt in the dark, although it happened sometimes that

men lost their way, and had to sleep in the bush all night. |