|

For about nine miles

our course lay along the south bank of the Thompson, close by the

water’s edge. The scenery of the river resembled that of such parts of

the Fraser where the trail lay along its shore—a shelving bank of large

boulders, covered in the summer with water. Coming to the Nicowameen

River,—where, it is said, gold was first found in British Columbia by an

Indian who, stooping to drink, saw a rich nugget glittering in the

water, which he carried to Mr. McLean, the officer in charge of Fort

Kamloops,—we turned off, and, crossing a mountain on our right, found

ourselves in a long, narrow valley, in which I saw the first land I had

as yet found that seemed unmistakeably fit for agricultural purposes.

From this time all the way to Kamloops the aspect of the country had

completely changed from that of the Fraser below Lytton; and we passed

through a succession of valleys sufficiently clear of timber to make

settling easy, yet with enough for building purposes, well watered, and

covered with a long, sweet grass. There are no prairies in British

Columbia, but it consists of what is called rolling country—that is,

long valleys from one to three or four miles wide, divided one from the

other by mountain ridges. Through the centre of these runs usually a

river, and in some cases may be seen a chain of small lakes. In summer,

when the water is high, streams and lakes meet, and the valleys become

sheets of water, dotted with large islands. At such a time it is very

curious to see the same river flowing diverse ways, as you may at almost

all the watersheds or turning-points of the water.

After passing along the first of these valleys, in which many trees had

been felled, and two log-huts erected, most probably for the sake of

claiming pre-emption, we passed through a gorge of the mountains, and

came out in view of the Nicola River, flowing some 600 or 800 feet below

us. The view from this spot was one of the most lovely I ever saw in

British Columbia. It was a fine, clear May day. The sun shone brightly,

giving a warmth and freshness to the hill-side, which sloped to the

water’s edge, not in craggy, precipitous masses like those of the canons

on the Fraser River, but clothed with long, soft grass, and bright with

the numberless wild flowers which grow so luxuriantly in this country.

Unlike them, too, instead of terminating abruptly at the water’s edge,

they sloped down to it in plateaux a mile or so in breadth, terminating

sometimes in steep, perpendicular banks, but as often sweeping down

gradually to a neutral ground of reeds and swamp, yet always vying with

the hill-sides in fertility and luxuriance. Between these banks the

Nicola coursed with great rapidity, leaping over the many rocks which

check its progress, and sweeping round the numerous small islets that

dot its surface.

It is very difficult to impress the reader with the beauty of the view

on which we stood gazing, unwilling to tear ourselves from it. As yet we

had seen nothing at all equal to it in British Columbia. The shores of

the coast are lined with dense, almost impenetrable forests, while the

Fraser cuts its way through steep and rugged mountains. It is true that

between Forts Langley and Hope there is some level land on either side

of the river, but even there you see a mountain barrier rise in the near

horizon, and feel sure that it must be scaled before rich fertile land

like this can be readied.

It was about three in the afternoon when we reached the Nicola River.

Coming to where it should be forded, we found that we had to pay a heavy

price for the sunny weather that had seemed so welcome, but which had

melted so much snow among the mountains, as to swell the river and make

it nearly impassable. However, it must be crossed somehow; and now we

found the advantage of having horses with us. Removing their loads, two

of the Indians swam the horses across. So swift was the swollen stream,

that, although it could not have been more than 100 yards wide, they

were swept at least half-a-mile down the river before they could gain a

footing on the opposite shore. Next we crossed, only getting over one at

a time, as the other had to swim the horses back; and lastly the baggage

was taken over. It was rather a lengthy process, and by the time it was

all done night was setting in, and it was time to camp.

Next morning we followed the course of the Nicola Eiver, until, during

the second day, we came up with the Lake. Here for the first time I saw

mounted Indians of the interior. They were as yet uncontaminated by

intercourse with white men: indeed all they had ever seen were the

people of the Hudson Bay Company stationed at Fort Kamloops. When we

camped overnight, I had no idea that we were in the close proximity of

Indians, and upon waking in the morning I was not a little surprised to

see an old Indian on horseback looking into the tent. Tom at once

introduced him as N5-as-is-ticun, the chief of the Skowtous tribe, and a

connection of his own, and very soon a large number came riding up to

our encampment, all fairly mounted on light yet fleet horses. My new

friend with the long name was very friendly and sent one of his men to

his hut for a grouse, which he presented to us for breakfast, and which

Dr. Campbell and I ate with no little relish. It was one of the

willow-grouse, which is found commonly both in Vancouver Island and on

the mainland.

Coming out of the tent—(it was quite dark when we had camped the night

before)—I found that we were upon rising ground, with a river flowing

beneath us, and that beyond a wide valley of undulating land extended

for several miles, which was dotted with Indian villages, the smoke of

whose fires was rising into the clear air, while over it we could see

Indian horsemen galloping about in various directions. The old chief

informed me that these were the homes of his tribe, the Skowtous, and

that his domain extended as far as the Thompson River, which divided him

from the Shu swap Indians.

Upon my telling him whither I was going, the chief at once expressed a

desire to accompany us through his territory, and offered us horses for

the journey. These, for several reasons, we declined; but we accepted

the offer of his company, and in a little while he joined us with a

staff of eight or ten of his tribe, all well mounted. Passing through

another fine valley about ten o’clock, we came to the Nicola Lake. This

lake is about fourteen miles long by one to two wide, and lies nearly

north and south. Its Indian name is “Smee-haat-loo,” but it has long

been called the Nicola, after an old chief of the Shuswap Indians. Its

banks are low, except in one place on the west side, where a

perpendicular granitic cliff barred our progress and compelled the

horsemen of our party to take a considerable detour to avoid it. Upon

the west side of the lake the mountains approach it closely; but on the

east, northward of a mountain about 2000 feet high, called by the

natives Wha-hat-cliallso (Otter) Mountain, two rivers run into it from

large valleys, in which there appears to be, and according to my native

friend there is, some very good land. These rivers are called

respectively McDonald and Bodinion.

A small chain of lakes or ponds stretches eastward from the Nicola in an

almost unbroken line to the Thompson River. Passing these, we ascended

the side of a mountain called by the natives Skye-ta-ken, upon the

summit of which we were, as nearly as I could estimate, 3600 feet above

the sea. The view from hence was very extensive and beautiful, ranging

as far as the Semilkameen Valley and the Shuswap Lake, and disclosing a

fine tract of grass land which will some day become a noble grazing

country. Descending the mountain-side, we crossed a succession of low

grassy hills, coming in time to the Thompson River.

It was about 8 o’clock in the morning when we came here, and found

ourselves in sight of Kamloops. The view from where we stood was very

beautiful. A hundred feet below us the Thompson, some 300 yards in

width, flowed leisurely past us. Opposite, running directly towards us

and meeting the larger river nearly at right angles, was the North

River, at its junction with the Thompson wider even than that stream;

and between them stretched a wide delta or alluvial plain, which was

continued some eight or ten miles until the mountains closed in upon the

river so nearly as only just to leave a narrow pathway by the water’s

edge. At this fork and on the west side stood Fort Kamloops, enclosed

within pickets; and opposite it was the village of the Shuswap Indians.

Both the plain and mountains were covered with grass and early spring

wild flowers.

We descended to the river-side, and our Indian companions shouted until

a canoe was sent across, in which we embarked and paddled over to the

Fort. Kamloops differed in no respect from other forts of the Hudson Bay

Company that I had seen—being a mere stockade enclosing six or eight

buildings, with a gateway at each end. Introducing ourselves to Mr.

M‘Lean, the Company’s officer in charge of the fort and district, we

were most cordially received, and, with the hospitality common to these

gentlemen, invited to stay in his quarters for the few days we must

remain here.

At this time the only other officer at the Fort was Mr. Manson. With

them, however, was staying a Roman Catholic priest, who, having got into

some trouble with the Indians of the Okanagan country, had thought it

prudent to leave that district and take up his abode for a time at

Kamloops. The life which these gentlemen of the great Fur Company lead

at their inland stations must necessarily be somewhat dull and

uneventful; but they have their wives and families with them, and grow,

I believe, so attached to this mode of existence as rarely to care to

exchange it for another. As it happened we visited them just as the one

stirring event of the season was expected—the arrival of the great Fur

Brigade from the north.

It may be well if I pause here to describe, in as few words as possible,

the position of the Hudson Bay Company in these districts, of which

until lately, they formed the sole white population. Those who have seen

the “fur traders” only at their seaports, can form but a very inadequate

idea of the men of the inland stations.

Inland you find men who, having gone from England, or more frequently

Scotland, as boys of fourteen or sixteen, have lived ever since in the

wilds, never seeing any of their white fellow-creatures, but the two or

three stationed with them, except when the annual “Fur Brigade” called

at their posts. They are almost all married and have large families,

their wives being generally half-breed children of the older servants of

the Company. Marriage has always been encouraged amongst them to the

utmost, as it effectually attaches a man to the country, and tends to

prevent any glaring immoralities among the subordinates, which if not

checked would soon lead to an unsafe familiarity with the neighbouring

Indians, and render the maintenance of the post very difficult, if not

impossible.

In the Company’s

service there are three grades of officers —the “Clerk,” “Chief Trader,”

and “Chief Factor.” The clerk is paid a regular salary of 100?. to 150?.

per annum, and he has his mess found him, which is estimated by the

Company to be worth another 100?. a-year. In this grade they are usually

kept 14 or 15 years, though interest with the directors or great

efficiency sometimes enables a man to get his promotion in 10 or 12

years. He then becomes a chief trader, and, instead of being a salaried

servant, is a shareholder, his pay varying with the value of the year’s

furs from 400?. to as high as 700?. or 800?. The mode in which he

receives his share is somewhat peculiar. The accounts of the Company are

made up at intervals of four years, and no pay is given to the higher

servants—i. e. the shareholders—until this is done. Thus a man who is

made a chief trader in 1862, will get no pay till 1866, when the

dividends for the former year are declared. Of course in the long run

this is the same thing; as, if a man retires in 1862, he keeps on his

full pay till 1866, when he is paid his dividend for 1862; and no real

inconvenience is felt, as the Company always lends whatever moneys are

required, within certain limits, and indeed prefers its officers being

in its debt. The posts of chief factors are filled up as vacancies

occur, the number being limited. A man is generally a chief trader for

15 to 20 years before he reaches this—the highest step in the service

The chief factor’s share varies from 800l. to 1500'. per annum. Every

station is, as a rule, in charge of a chief trader, chief factors having

the control of several posts, or a district, as it is called, or being

stationed at head-quarters.

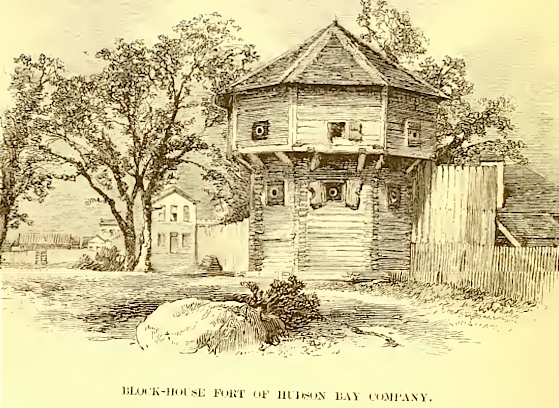

As all Hudson Bay posts are much alike, I will here describe them

generally. They are built usually in the form of a square, or nearly so,

of about 100 yards. This space is picketed in with logs of timber,

driven into the ground, and rising 15 to 20 feet above it. In two of the

corners is usually reared a wooden bastion, sufficiently high to enable

the garrison to see a considerable distance over the country. In the

gallery of the bastion five or six small guns—six or twelve pounders—are

mounted, covered in, and used with regular ports like those of a ship;

while the ground-floor serves for the magazine. Inside the pickets are

six or eight houses: one containing the mess-room for the officers at

the post, and their dwelling-lionse, where the number of them is small;

two or three others—the number of course depending on the strength of

the post,— which seldom exceeds a dozen men—being devoted to the

trappers, voyageurs, &c. Another serves for the Indian trading-store,

and one for the furs, which, as will be hereafter explained, remain in

store at the inland posts during the greater part of the year.

Some of these forts have seen some hard fighting, and have often been as

gallantly defended against Indians and the rival traders of the old

North-Western Company as military posts for the defence of which great

glory has been gained.

The day after our arrival at Kamloops we went across North River to the

Indian village, to pay a visit to the chief of the Shuswap tribe, who

was described to us as being somewhat of a notability. Here was the site

of the old fort of the Company, which some twelve years back, after the

murder of Mr. Black, the officer in charge of it, by the Indians, had

been removed by his successor to the opposite side of the river. No

doubt the old site was preferable to the new, which is subject to the

summer floods. Only the year before our visit, indeed, all the floors

had been started by the water, and the occupants of the fort buildings

had to move about in canoes.

We found the Shuswap chief located in a good substantial hut. The Indian

constructs but two kinds of abodes anywhere: one a permanent hut, in his

village ; the other a temporary one, to shelter himself when he is

moving about from place to place, fishing or collecting clams. In their

permanent houses the architectural peculiarity that strikes the observer

with most surprise is the solidity and size of the cross-beams. They

erect ten or twelve upright supports, according to the size of the hut,

the tops of which are notched to receive the beams; and it is a great

object with them to have as large a beam as possible, because, as it

must be raised by sheer strength and numbers, its size is supposed to

testify to the number and cordiality of the builders’ friends. The ends

of these huge beams—some of those I have seen being 40 to 50 feet long,

by two to three feet in diameter—are usually ornamented with the head of

some fish or animal, which, projecting beyond the wall, shows the crest

or distinguishing mark of the house. The sides of the building are

formed of large planks, wonderfully smooth considering that the Indians

use no plane, and until lately, indeed, had no axes. The interior of the

hut is divided into compartments, and, upon entering, you may see a fire

burning in each, uitli six or eight individuals huddled about it, their

dusky forms scarcely distinguishable in the cloud of white blinding

smoke, which has no other outlet than the door, or sometimes a hole in

the roof. Their temporary hut is constructed lightly of thin poles

covered with mats; but these, as I have said, are generally used only in

the summer, and upon their fishing-expeditions and travels. It is not,

however, unusual for the Indian to have a permanent residence in two or

three villages, in which case he usually makes one set of planks useful

for all, carrying them with him from place to place, and leaving only

the upright posts and beams stationary. They have been known, however,

from some superstitious reason, or because of sickness breaking out in a

place, to leave their villages with everything standing, and never to

return to them.

The building into which we were introduced was more like a regular

wooden house than an Indian hut. In the centre room, lying at length

upon a mattrass stretched upon the floor, was the chief of the Shuswap

Indians. His face was a very fine one, although sickness and pain had

worn it away terribly. His eyes were black, piercing, and restless; his

cheek-bones high, and the lips, naturally thin and close, had that

white, compressed look which tells so surely of constant suffering. Such

was St. Paul, as the Hudson Bay Company called him, or Jean Baptiste

Lolo, as he had been named by the Roman Catholic priests who were in

this district many years before. Behind him stood his wife, and

presently he summoned two handsome-looking Indian girls, whom he

introduced to us as his daughters. St. Paul received us lying upon his

mattrass, and apologized in French for not having risen at our entrance.

He asked Mr. M‘Lean to explain that he was a cripple. Many years back it

appeared St. Paul became convinced there was something wrong with his

knee. Having no faith in the medicine-men of his tribe, and there being

no white doctor near, the poor savage actually commenced cutting a way

to the bone, under the impression that it needed cleansing. In time, at

the cost of course of great personal suffering, he succeeded in boring a

hole through the bone, which he keeps open by constantly syringing water

through it. Mr. M‘Lean described him as a man of very determined

character, who had been upon many occasions most useful to him and his

predecessors at the fort. Although obliged to lie in his bed sometimes

for days together, his sway over his tribe is perfect, and, weak as he

is, he rules them more by fear than love. Upon my remarking casually

that I wondered he was not sometimes afraid of some or other of his

people taking advantage of his comparatively helpless condition, he

heard me with a grim smile, and for answer turned back his pillow, where

a loaded gun and a naked sword lay ready to his hand. Upon our rising to

leave Mr. M‘Lean whispered that our host would take it ill if he were

not asked to accompany us; and this being done, to my surprise St. Paul

at once assented. Being assisted to rise, he hobbled to the door on

crutches, and, having been with considerable difficulty got into the

saddle, rode about all the day with us.

The mountain up which Mr. M‘Lean guided us was one of two standing side

by side opposite the fort, and about a mile from it. Its companion had

been named Roches des Femmes, from the fact that, in summer, many Indian

women were to be seen scattered about its sides gathering berries and

moss. From its summit, at a height of some 1500 feet, we had a very fine

view of the land along the banks of the Thompson and North Rivers. It

appeared to be very good, and in this opinion we were confirmed by Mr.

51-Lean, who further informed us that the land at the head of the

Thompson River, and southward of that point to the Semilkameen Valley,

was equally fertile and valuable. Descending the mountain, which we

christened Mount St. Paul, in honour of the old chief, we lunched with

him, returning to the fort for a tea-dinner. Tea is a beverage drunk

usually at this and other meals. Indeed, Mr. M‘Lean informed us that he

took nothing else. Nor had total abstinence disagreed with him. A finer

or more handsome man I think I never saw, with long beard and

moustaches, and hair hanging in ringlets down his shoulders. The

Indians, we heard, had given him the sobriquet of the Bearded Chief.

On the following day we went out to see the bands of horses driven in,

and those that were past work selected for food. There were some two or

three hundred horses, of all sorts and ages, at the station. Just

outside the Fort were two pens, or corrals as they called them, and into

these the horses were driven. A few colts were chosen for breaking in,

and then the old mares, whose breeding-time was past, were selected

and—for it was upon horse-flesh principally that the Fort people

lived—driven out to be killed, skinned, and salted down.

It was curious to note the close discipline in which the stud-horses of

each band kept their mares. There are generally three studs in each

band, and while they were in the corral they might be seen galloping

about, administering a kick here and a bite there. For a few minutes,

perhaps, one would stand still and look about him, then suddenly,

without the least perceptible cause or provocation, he would make a rush

at some unfortunate mare, and bite or kick her severely.

The mountain-sides in the neighbourhood of Kamloops are covered with a

bright yellow moss, called by the Indians Quillmarcar. It is much used

by them as a dye, and when boiled gives them that yellow which is so

familiar to those who have travelled among them in their dog-hair mats

and other native work. There is also a kind of lichen which grows here,

called by them “Whyelkiue,” and which is one of their most important

articles of food. In its natural state it somewhat resembles horse-hair,

and being boiled it is pressed into cakes, three or four inches thick,

looking not unlike our gingerbread. Its taste is very earthy and rather

bitter. Our companion, St. Paul, gave us this, which they call “Wheela,”

with milk, upon our return to his hut, but two or three mouthfuls were

all we cared to take.

While at the Port I learned that the rivers between Kamloops and

Pavilion on the Fraser, for which place I had determined to start, were

likely to be so swollen with the late thaw that we should not be able to

cross them without horses. Accordingly it became necessary to make

arrangements for mounting our party. We discovered that the best way of

effecting this would be to seek the aid of St. Paul, who happened to be

the possessor of a score or more horses. Willing as Mr. M‘Lean was to

render us every assistance, he could himself spare us no horses, a

message having been received from the officer in charge of the Fur

Brigade, which was expected to arrive daily, saying that he should

require all they could supply him with. Terms were accordingly made with

St. Paul, and upon their completion, to my surprise, the old chief said

that he should like to accompany us. We were very glad of this, if for

two reasons only. In the first place, Tom, my interpreter, had fallen

ill, and, as I have before said, his friend steadily refused to leave

him, so that we were without a guide, and the information we had lately

received convinced us that, without the aid of some one well acquainted

with the fords, it would he difficult, if not altogether impossible, to

cross the rivers that lay in our path. Secondly, St. Paul possessed

considerable influence with the Indian tribes through which we had to

pass, and we might feel pretty sure that he would, if he lived through

the journey, conduct us safely to its end.

On the morning of the 14tb May, then, into the Fort rode St. Paul, with

an escort of eight men mounted, and with led horses for Dr. Campbell and

myself. Four of these men were to have charge of our packages; the rest

formed his own bodyguards, two being the old chief’s sons. We were soon

ready to start, and, following the course of the Thompson for about

twelve miles, came to the river Tranquille. Here Mr. M‘Lean, who had

ridden so far, was compelled to part company with us, regretting that,

the hourly expected arrival of the Fur Brigade prevented his leaving

Kamloops for any length of time.

The plains that lay along the course of the Thompson seemed rather light

and sandy, but in spots good land was observable. Crossing the

Tranquille close to its mouth without any difficulty, the water being

little above our horses’ knees, and turning to the right, we mounted a

somewhat steep gorge leading to a long, narrow valley running nearly

parallel to the Thompson River, but quite out of sight of it. Emerging

from this pass, we descended to Lake Kamloops, along the side of which

we held until night, camping at a spot called the Coppermine, where the

Indians said they had found perfectly pure specimens of that metal. We

made a very careful examination of the place, and although there were

unmistakeable signs of the presence of copper, we saw nothing to cause

us to doubt that the Indian’s story was not, as usual, very much

overcharged.

At this spot the trail by which the Fur Brigade would travel to Fort

Kamloops met that along which we were journeying, and St. Paul was very

anxious that we should deposit a note for the officer in command of it,

expressive of his, the chief’s, good wishes. I was rather puzzled what

to say, but St. Paul was so urgent that I should, as he expressed it,

“Bon jour Mr. Peter,” that I scrawled a few hurried lines; and when a

year later in Victoria I chanced to meet Mr. Peter Ogden, the officer

who had been in charge of the Brigade, I learnt that upon his arrival at

Coppermine he had found my note. It was not without regret that I missed

seeing the Pur Brigade. It is one of those old institutions of this wild

and beautiful country, which must give way before the approach of

civilisation. The time will come—soon, perhaps—when such a sight as a

train of some 200 horses, laden with fur-packages, winding their way

through the rough mountain-passes of British Columbia, will be

unfamiliar as that of a canoe upon its rivers. No doubt the change will

be for the better, but it is sometimes hard to believe it. Of course it

is much more practical to ascend the Fraser in a river steamboat than to

make the journey in an Indian canoe; and perhaps, taking the chances of

an explosion into consideration, equally exciting; but it will be long

before I should prefer the former method of locomotion to the latter

when the weather is fine. With all its many inconveniences, there is

something marvellously pleasant in canoe travelling, with its tranquil,

gliding motion, the regular, splashless dip, dip of the paddles, the

wild chant of the Indian crew, or better still the songs of the Canadian

Voyageurs, keeping time to the pleasant chorus of “Ma belle Rosa” or “Le

beau Soldat.” Miss the Fur Brigade we did, however, and next morning we

pursued our way along the shore of the Kamloops Lake. The scenery here

was very pretty, and the lake was, we found, perfectly navigable for

steamers. Indeed it has since been proposed to start steamers here, and

run them past Kamloops for some miles up the North and Thompson Rivers,

from the latter of which a small portage would connect them with another

line of steamers to be stationed on the Okanagan Lakes.

About half-way along the north side of Kamloops Lake the trail passes

round a very steep and dangerous cliff, overhanging the deep water

below. A ledge barely wide enough to give the horses footing is the only

pathway. This pass, known as the Mauvais Bocher, was one of the most

unpleasant places I had ever ridden over; and I was not at all surprised

to hear that several horses had, with their riders, been precipitated

into the lake below. St. Paul told us that he had discovered a way along

a narrow gorge in the rear, by which this might be avoided, but that it

required some labour to clear it before it could be used. There is also

a trail upon the other side of the lake by which the passage of the

Mauvais Kocher might be avoided; and a horse-ferry had just been

established at its west end, which was very generally used by the

American packers from Walla-Walla. But travelling northward as we were,

had we followed this trail we should have had to cross the Thompson

twice.

A little below Shu swap Lake the Buonaparte River joins the Thompson.

This river is said to have its rise in Loon Lake, some 40 or 50 miles

north of the Thompson. At this point we left the Thompson and camped for

the night, by the side of the Riviere de la Cache, a small stream

flowing into the Buonaparte.

Next morning’s work commenced with fording the Buonaparte. It cost us

some time to find a suitable spot, the floods having made the ordinary

ford impassable ; but at last we managed to cross, the horses being now

and then swept off their legs into deep water, and having to swim for

it. En passant, I would remark that it is by no means so easy to swim a

horse across a rapid stream as it may seem to a horseman who has not

tried it; the rolling motion given to the animal by the swift current

making the rider very apt to lose his balance.

The Buonaparte, however, was not the most difficult river we had to

cross on this day’s journey. For at the Riviere Defent the water was

found to be so deep as to make it necessary to swim the horses all the

way a toss, without the chance of their gaining a footing from shore to

shore. AVe were particularly anxious to avoid this necessity on account

of the instruments, which would infallibly be damaged, and after a long

search we came upon the trunk of a tree by which Indians were evidently

accustomed to cross. To our annoyance, however, the river had risen so

high that this rough bridge was at least two feet under the water, which

tore over it with the rapidity of a mill-stream; so that, unless a rope

could be carried over and fastened at the other side to form a

balustrade, it seemed quite impossible to get ourselves and the luggage

across safely. However, St. Paul seemed determined that this should be

done, and several of his men stripping to the work endeavoured gallantly

to cross the river. As often, however, as they managed to get to the

middle of the primitive bridge, the elasticity of the tree, together

with the velocity of the current, sent them spinning off, and they were

swept down the stream, having to swim vigorously for their lives. After

many successive failures, we had almost made up our minds that we should

have to loiter by the river’s side for a day or so, until its waters

should have subsided—for there were no trees handy large enough to frame

a bridge with—when St. Paul, whose anger had risen at the ill-success of

each fresh attempt, to our astonishment leapt up—we were in lying on the

ground watching the baffled Indians—and throwing off his clothes ran

forward to their aid. In his weak and exhausted condition, we made sure

that the effort and excitement of such an attempt would act most

injuriously if not fatally upon him, and did our best to dissuade him

from making it. Nor were we altogether unselfish in this, perhaps, since

we knew that, if the old chief lost his life in our service, it would

not only be most painful to us, but that we should lose all the Indians,

who would infallibly return to Kamloops with his corpse, to take part in

his wake. However, the spirit of the old man was roused, and breaking

from us he was soon standing mid-stream, the rope in his hand, yelling

to his men, and swearing in a French jargon peculiar to himself, with a

zeal and originality that would have inspired the members of Captain

Shandy’s troop in the Low Countries with admiring envy. Very much to our

relief, as may be supposed, St. Paul succeeded in scrambling over the

fragile bridge with the agility of a monkey, and, the rope being made

fast to the other side, we crossed with comparative ease. Not, however,

without getting thoroughly wet and spoiling one of the instruments about

which I felt so anxious. With all my care, when I came to look at my

sextant, I found that it had been under water, and that the pieces of

wood that kept it in its place in the case had been loosened and were

floating about. Fortunately, however, I had a pocket one with me, so

that its loss was not so important as otherwise it would have been. All

now fairly over, we halted for breakfast. I had found before leaving

Kamloops that when travelling with the officers of the Hudson Bay

Company, St. Paul was always admitted to their mess, and upon starting I

had of course invited him to join ours. The Indian is so quick at

observing and imitating the manners of those with whom he is brought

into contact, that the old chief had learnt to conduct himself with

perfect composure and decorum, and the beef with which he had provided

himself on starting, proved a welcome addition to our bacon.

Following the course of the Buonaparte until its junction with the

Chapeau, we turned up the valley through which that river flows. There

is much good land along the Buonaparte; the whole being clothed with

long grass, of which the horses seemed very fond. We carried no fodder

with us on this expedition, turning the horses loose at night to graze.

They never strayed far. One of course was hobbled, and at daybreak an

Indian caught and mounted him, driving in the others.

We followed the course of the Chapeau until it opened into a large

valley running southward, in which the river rises, and through which

also another small river runs to join the Fraser, some 20 miles above

Lytton. Through this valley the Indians told us there was a trail by

which Lytton might be reached in two days.1 Taking a northerly

direction, we passed a small lake called Lake Crown, and soon came to

the Pavilion Lake. The mountains here are of limestone and rise abruptly

from the lake’s edge, causing the trail to be somewhat narrow and

dangerous. But this place and the Mauvais Boeher on the Shuswap Lake

were the only spots upon the whole of our route from Kamloops to

Pavilion, along which waggons might not have travelled with ease. Of

course in saying this I suppose the rivers bridged.

Lake Pavilion is six miles long by one wide. On its south bank there is

a mountain some 3000 or 4000 feet high, which is topped with a very

remarkable peak, not at all unlike a watch-tower built there to keep a

look-out over the Fraser. The Indians call this Skillipaalock, which

being interpreted means a finger or joint.

Just beyond the Pavilion Lake we passed a log hut, near which a farmer

was ploughing—it was the first time I had seen such an implement in use

in British Columbia—very diligently with two horses. This farm, of which

I shall have occasion to speak hereafter, had, we found, been occupied

by a couple of Americans for more than a year. They described their land

as good, and spoke well of their prospects. Their principal occupation

at present consisted in growing vegetables, &c., for the miners. The

Pavilion River ran close by their hut, giving them a plentiful supply of

water. It is a small stream flowing from the lake, and discharging

itself into the Fraser at Pavilion.

Altogether we were five days making the journey from Kamloops to

Pavilion, although the distance is a little under 100 miles. We had been

much impeded, however, by the swollen state of the rivers, and had

ridden very leisurely, constantly stopping to take bearings and make

observations generally. Pavilion stands upon a terrace very similar to

that upon which Lytton is situated, but some 100 feet or so higher. It

consisted at that time of a score or so of miners’ huts, and had gained

its name from the fact of an Indian chief having been buried here, over

whose grave, after the fashion of this people, a large white flag had

been kept flying. It has since become a much more important place,

forming a sort of head-quarters for the miners and the mule-trains, who

from Pavilion, branch north and south to the diggings at Alexandria,

Cariboo, and Kamloops.

We wished much to have pushed on from Pavilion to Alexandria, although

at that time the diggings at Cariboo and Quesnelle were unthought of,

and Alexandria was only known as a more distant station of the Hudson

Bay Company. But poor St. Paul was knocked up by the efforts he had

already made, and in such suffering that it was quite impossible to

expect him to accompany us further. Almost all the way, indeed, he had

been obliged to ride his horse in side-saddle fashion, and his exertions

at the Defant River had used up what little strength he had, besides

aggravating the pain he always suffered from his wounded knee.

Accordingly, these considerations, coupled with the expense of preparing

a new party for the trip, and the fact that we had already done more and

gone farther than had been marked out for me in the Governor’s programme

of instructions, determined us to return by the Harrison-Lilloett route

to the mouth of the Fraser. After staying three days at Pavilion, Durine:

which time the wind blew and the dust tormented us much as it had done

at Lytton, we bade St. Paul and his party adieu, starting for Cayoosh,

or as it is now called Lilloett.

I may say here that while at Pavilion we experienced the only trouble

with Indians I have ever had while travelling. A half-breed who was

journeying with us, although not of our party, having a bullock to sell,

disposed of it for 200 or 300 dollars, purchasing with part of its price

a keg of whisky. Upon the contents of this he very soon got drunk, and

must needs reduce the rest of our party to the same plight; so that in

the dead of the night I was roused by the sound of scuffling going on

outside the tent, and became aware of what all who have had any

experience in camping will agree with me in calling a very disagreeable

sensation, caused by a number of men tumbling over the tent-ropes. Going

out, we found that St. Paul and one of his sons were the only sober men

of our escort. Fortunately my gun was the only one belonging to the

party, and most of the knives were in St. Paul’s tent, or the

consequences might have been serious. As it was, the offending

half-breed was driven away, two or three of the more refractory Indians

knocked down, and peace re-established, in a way we, without St. Paul,

would have found it very difficult to accomplish.

It may be interesting to note that when I was at Pavilion, flour was

selling at 35 cents (Is. 5Jd.) the pound, and bacon at 75 cents (3s.) A

few months earlier in the winter these high prices had been more than

double. The charges for the carriage of goods were also very high, as

much as 25 cents per lb., being paid from Pavilion to Kamloops, while to

Big Bar, a place only 18 miles distant, the rate was 8 cents, or 1d.

We were now left without any attendants, but as we knew that there were

regular mule-trains on the Harrison-Lilloett route, we determined only

to engage two horses to take our baggage as far as Lilloett, and thence

to accompany a train down to Port Douglas.

We started on the morning of the 23rd May, and proceeded towards

Fountain, keeping the left bank of the Fraser, and passing along a fair

trail over very good land; our party consisting of our two selves, a

couple of horses, and one man, who served as guide, driver, and packer.

Fountain is a flat at a sharp turn in the river 12 miles below Pavilion,

and derives its name from a small natural fountain spouting up in the

middle of it. It is a much prettier site than Pavilion, and the

river-bend shelters it from the gusty north and south winds which I have

mentioned as being so very uncomfortable both at Lytton and Pavilion.

About three miles below Fountain, and on the opposite side, the Bridge

River (or Hoystien, as the Indians call it) joins the Fraser. This river

takes its English name from the fact of the Indians having made a bridge

across its mouth, which was afterwards pulled down by two enterprising

citizens, who constructed another one, for crossing which they charge

the miners twenty-five cents. Bridge River rises in some lakes 50 or 60

miles from its mouth. I have never visited them, but from information

obtained at various times from Indians, I believe that the Bridge,

Lilloett, Squaw-misht, and Clahoose Rivers, all of which will be

mentioned hereafter, take their rise in these same lakes, which, so far

as I could ascertain, lie very high up in a mountain-basin, nearly north

of Desolation Sound.

The Bridge River also runs through two lakes about 40 miles from its

junction with the Fraser. I once met a miner who told me he had visited

these lakes, and thought the land round them very good and well adapted

for agriculture. A man at Pavilion also told me he had travelled from

Chilcotin Fort to these lakes by a valley parallel to the Fraser, and

had then descended the river. I am inclined, however, to doubt whether

these lakes lie so far as 40 miles up the river, as I have found that

travellers almost always overestimate distances when going up a rapid

river.

Just before coming to the Bridge River our guide pointed to a deserted

bar opposite, and said, “Last summer I and two others made 600 dollars

(200l.) each in a week there.” “Why did you leave it?” I asked. “Oh, we

thought we had done enough,” was the reply; “and went to Victoria and

spent it all in two or three weeks: and when I came up the river again I

hadn’t a cent, and so I took to packing.” This is the story nearly every

miner has to tell. If you question him, you will find that at some time

or other he was worth several thousand dollars. He may still, perhaps,

have a gold watch, or a large brooch stuck in the front of his

mining-shirt, as a memento of that time, but all the rest has gone.

About a mile and a half below the Bridge River, at a place called French

Bar, is a ferry, which we crossed. After crossing we came upon a fine

flat, lightly timbered with small trees, which continued to Lilloett,

which is about two miles from the ferry.

Lilloett is a very pretty site, on the whole decidedly the best I saw on

the Fraser River. It stands upon a plateau some hundred feet above the

river. On the opposite side of the Fraser is another large plateau on

which the Hudson Bay Company were building a fort when I was there,

which was to be named Fort Berens, after one of their directors.

Lilloett has now grown into a somewhat important town, situated as it is

at the north end of the Harrison-Lilloett route, at its junction with

the Fraser.

The Inkumtch River runs in at the south end of the flat on which the

town stands. It is a rapid stream, 40 or 50 yards wide at its mouth, and

not fordable in summer.

At Lilloett we found that the pack-trains came up to Port Anderson at

the south end of the lake of that name, and that we must take boat

across it and Lake Seton. We procured two or three Indians to carry our

baggage and instruments to Lake Seton, which was about four miles off;

but finding upon calculation that the expense of conveying our

cooking-utensils, &c., would be considerably more than their original

cost, are determined to leave them behind for the benefit of any

travellers who might pass that way. We knew we could not starve, as

there were several “restaurants” on the trail down; still Ave took some

bread with us in case of accidents. It is very awkward at first when you

have to make any purchases at these places, getting your change in

gold-dust. There is little or no coin in use among the miners, and they

pay and transact all business in gold-dust. For a purse every one

carries a chamois-leather bag containing the dust. If you offer coin,

they take out their scales and weigh you off your change. I have

mentioned the fact of there being “restaurants” all along the Lilloett

portages, and I should have meutioned their existence in the canons of

the Fraser also. All such places in this country are called

“restaurants,” although they are simply huts, where the traveller can

obtain a meal of bacon, beaus, bread, salt butter, and tea or coffee,

for a dollar; while, if he has no tent with him, he can select the

softest plank in the floor to sleep on. Of course these places vary with

their situation. At those on the Lower Fraser meals can uoav, I believe,

be had for half-a-dollar, and sometimes eggs, beef, and vegetables can

be got. On the other hand, at those far up the river I paid a dollar and

a half for the bare miner’s fare of bacon, beans, and bread. Miners

suffer a great deal from inflamed mouths, which is very generally

attributed to their constant diet of bacon. By some, however, it is

attributed to the water of the river.

We started for Lake Seton on the afternoon of the same day that we

reached Lilloett, and, turning off from the Fraser River, followed the

Inkumtch, up a deep narrow valley between two magnificent mountains some

5000 feet high. About half-way to Lake Seton are found that the river

divided; one branch coming from the lake and the other down a gorge on

the left. This branch is said to take its rise in a lake some miles

below Lilloett, and between the lake of that name and the Fraser River.

After walking about four miles we emerged from the mountain-pass and

came out on Lake Seton. Here we had to get a canoe to cross the river,

as the boatmen’s huts were on the other side of it. We crossed, and, as

it was late, pitched our tent and made arrangements for a boat with four

men to take us over the lake in the morning.

In the morning accordingly we started, and had a most tedious cold pull

of four hours’ duration. On this lake, and, indeed, on all the chain of

lakes, it blows almost incessantly from the southward during the day,

the wind commencing at nine or ten and dying away at four or five,

leaving the mornings and evenings calm. Lake Seton and Lake Anderson are

very like each other, although the latter trends much more to the

southward than the former. Both are very deep, and bounded by mountains

of 3000 to 5000 feet, which rise so abruptly from the water as to leave

no room for a road even along their banks without a good deal of

blasting and levelling. These mountains are densely wooded, like those

along the coast. The two lakes are each 14 or 15 miles long, and are

separated by a neck of land a mile and a half in extent, with a stream

of 20 or 30 yards wide running through it. There is a small restaurant

at the south end of Lake Seton, and another larger one at the south end

of Lake Anderson, for the entertainment of the muleteers, &c., who sleep

there after coming from Port Pemberton; returning on the following day.

We were lucky enough to find a mule-train starting next morning, and

arranged to accompany it. At this time the charge was eight cents (4bd.)

per pound for packing goods along this portage, the length of which is

about 25 miles. This portage, which extends from Port Anderson to Port

Pemberton on the Lilloett Lake, was at first called the Birkenhead

Portage, but since has acquired the much more appropriate name of

Mosquito Portage. When I passed along it the trail was on the whole

good, though in some parts very indifferent. But this summer will

probably see a waggon-road constructed from one end to the other. The

valley through which the road lies averages about 1500 yards in width.

At Port Anderson, however, where it is widest, it is about two miles

broad. There is a stream running the whole way along it, having a

watershed at the Summit Lake about nine miles from Port Anderson. From

this lake, when the water is high, the rivers run either way, one into

Lake Anderson and the other into the Lilloett River, just above Port

Pemberton. When the waters are out the north branch only runs from the

lake, the true source of the south branch being a few yards from it. The

Summit Lake is, as nearly as I could estimate it, 800 feet above Lake

Anderson and 1800 above the sea. The banks of the river are low and

covered with willows, &c., and there are a number of small streams

running into it at intervals all the way along. There are only two of

these of any size, which come down rather large valleys. The mountains

on either side range from 1000 to 5000 feet high, and are generally very

steep. All the level spots are covered with wild peas, vetches, lettuce,

and several sorts of berries. The mosquitoes along the portage were more

troublesome than I had ever found them (at that time) elsewhere.

Five or six miles before reaching Port Pemberton the valley opens out,

and there are several miles of splendid grass-land on the right, through

which the Lilloett River runs into the lake of the same name. On this

occasion I had not much opportunity for observing these Lilloett

meadows, as they are called, but upon my next visit I came upon them by

the Lilloett Valley, and walked all over them. Several agricultural

settlers were already there, and it is a lovely spot for settlement. The

river here divides into several small streams, which run through the

plain in all directions, cutting it up into fine fields, and greatly

adding to its beauty.

Port Pemberton is at the north end of Lilloett Lake, and consists of a

couple of restaurants and half-a-dozen huts, occupied by muleteers and

boatmen. The great objection to its site is that there is a large flat

off it, which in winter dries the whole way across the lake, so that

even boats cannot get to the town, and all goods have to be landed a

quarter of a mile below it. This is, however, quite unavoidable, as

there is no place further down the lake on which to build a town, the

mountains rising nearly perpendicularly from the water. When the road

was in contemplation Captain Grant, R.E., who had command of the men at

work upon it, examined the meadows with a view of seeing if it would

answer better to take the road from the other side of the lake, but he

decided against it. This lake is in appearance much like the others I

have described.

We got across the Lilloett Lake the same afternoon, sleeping that night

at Port Lilloett. Early next morning we again set out. It rained the

whole night while we were at Port Lilloett, and we were informed that

this was the first rain that had fallen since the beginning of the year.

This illustrates the partiality of the rain in this region, where

January, February, March, and April had passed without a shower, while

at Victoria it had rained almost incessantly for the first half of that

period.

Next morning we started for Port Douglas. At the time I first went along

this—which I have before said is called the Douglas Portage—there was

only the trail which had been cut by the party who had volunteered for

the purpose. Having no engineer with them, they gave themselves a vast

deal more trouble than there was any occasion for, by making the trail

pass over all sorts of ridges which might have been avoided. Eight miles

from Port Lilloett the traveller comes to a very curious hot spring,

called St. Agnes’ Well, so named from one of the Governor’s daughters.

It runs in a small stream out of a mass of conglomerate into a natural

basin at its foot, overflowing which it finds its way into the Lilloett

River. Here have been built a restaurant and bathhouse. On my first

visit I stopped to bathe, and found the water in the basin hotter than I

could bear. Unfortunately my thermometer was only marked to 120°, up to

which the mercury flew instantly. I believe its temperature has since

been ascertained to be 180° Fahr.

I have said that the Lilloett River runs down nearly to Port Douglas.

When I passed down no canoes were able to ascend, though some went down

the stream. In winter, however, a good deal of traffic is carried on by

the river, at a cost less than the land-carriage. This river varies

greatly in width, ranging from 50 to 150 yards. About nine miles below

Port Lilloett a large stream, called by the Indians the Amockwa, joins

it; and about the same distance above Port Douglas another river, called

the Zoalklun, runs into it, coming, it is said, from a lake called

Zoalkluck. Two large hills have to be crossed on this portage, which

have been named Sevastopol and Gibraltar; the latter rises just before

entering Port Douglas, and on its south side are the finest cedars I saw

in the whole country. There is a stream running down a gorge in this

hill, and a large water-mill has been erected about half-a-mile from the

town, so that I dare say considerable havoc has been made among the

cedars by this time.

The scenery on the Harrison Lake is much finer than on the upper ones.

It is also much longer, being 45 miles in length, and four or five

broad. There are several islands upon it, and some large and apparently

fertile valleys running into it. In some of these silver has been found,

and one or more companies have been started to work it.

During our journey we found the change of temperature very great and

sudden. I have seen the thermometer 31° in the shade in the morning, 95°

at noon, and 40° again the same evening.

On the 19th June we rejoined the .‘Plumper’ at Esquimalt. |