|

In this chapter I

propose to treat of the resources of Her Majesty’s dominions in the

Pacific, comprising, as the reader already knows, the country between

the 49° and 54° 40' north latitude and the Rocky Mountains and Pacific

Ocean, Kith the islands of the coast comprised in those limits. In doing

so, I shall speak of the general condition of the country and its

probable future ; offering, at the same time, an account of the various

routes by which emigrants may reach it, with the approximate cost of

each. I shall also have occasion to speak of the routes that may

hereafter be opened up to the great gold-fields of the Pacific. In so

doing I shall not hesitate to avail myself of the information afforded

by Parliamentary papers, the labours of others, and the press; selecting

from these and more private sources such facts and suggestions as my own

experience of the country may lead me to approve.

The claims of the Hudson Bay Company to the possession of the territory

they have so long held by grants from the Crown, renewed from time to

time through a couple of centuries, have been so fully discussed in and

out of Parliament that it is needless for me now to enter upon this

subject. I think, however, that those who blame the Company’s rule do

not sufficiently consider the vast difficulties with which these traders

have had to contend. Living, as their assailants do, under the

protection of British law, they are little capable of appreciating the

absolute necessity of many apparently cruel acts, which however were

directly traceable to the instinct of self-preservation. I do not mean

for a moment to deny that there were acts of cruelty committed by the

Hudson Bay people, which even this consideration could not justify; hut

I do maintain that a handful of white men, hundreds of miles away from

the protection of their own flag, surrounded by a population, among whom

were many both fierce and treacherous, should not, in common justice, be

judged by the rules which apply to a more civilised state of existence.

One of the main charges against the officers of the Hudson Bay Company

in what was then Hew Caledonia is, that while their lease of the country

specified that offences above a certain degree should be tried by the

Courts of Canada, they, instead of sending criminals there, executed a

species of retaliatory justice themselves. But it was simply ridiculous

to expect any such slow and awkward machinery for the repression or

punishment of crime to be used. As it was, the Company, under that

instinct of self-preservation I have before put forward in their defence,

appointed the best men they had to the charge of them posts, and left

them to hold their own and maintain law and order among the Indians as

best they could. No one who has travelled much among the natives of

British Columbia can fail to be convinced that one result of the

Company’s rule has been that the white man is respected by them

everywhere. Even the missionaries —who complain of the little that has

been done during these many years for the spiritual welfare of the

Indian tribes— must admit that but for their familiarity with the

traders, and the opinion they have thereby gained of the honesty and

justice of the Englishman generally, their reception would be very

different to what it now is.

Again; the abuse which has been showered upon the long and undisturbed

monopoly of the trade of these regions enjoyed by the Hudson Bay Company

would have been more deserved had their possession of them been valued

or envied by others. As it was, the country was unheeded by emigrants,

neglected by the Government, and but for the Company’s tenure of it,

might have fallen into the hands of Russia, France, the United States,

or any other nation that cared to take it.

The time has undoubtedly come when their pretensions to its longer

possession should be rightly unheeded. But I think it should have been

resumed by the English Government with thanks for the Company’s care of

it, rather than with vague distrust and suspicion of their past

occupation. I for one feel convinced that I should have found it

impossible to travel about British Columbia with the ease and freedom

from danger which I felt, but for the influence of the Hudson Bay

Company exerted in my favour. The name of Mr. Douglas, as I have more

than once said, proved to be a talisman, wherever it was mentioned, that

secured me respect and help. The reports of Captain Palliser show also

that the success of his three years’ exploration in the Rocky Mountains

was owing, in no small degree, to the influence and assistance rendered

him by the Company. The following extract from one of his despatches

will, I think, serve to illustrate this sufficiently. One of a

deputation of Indians who waited upon him, an old chief, spoke thus:—

“I do not ask for presents, although I am poor and my people are hungry.

But I know that you have come straight from the great country, and we

know that no man from that country ever came to us and lied. I want you

to declare to us truthfully what the great Queen of your country intends

to do to us when she takes the country from the Fur Company’s people.

All around I see the smoke of the white men to arise. The Longknives

(Americans) are trading with our neighbours for their land, and they are

cheating and deceiving them.”

Who but the officers and men of this much-abused Company could have

inspired this spokesman of the Indian people with the trust in the word

of an Englishman which is here expressed?

Again; any one who knows the condition of the Indians in British

Columbia, and will take the trouble to compare it with that of the

tribes in American territory, must come to the conclusion that some

salutary influences—wanting there —have been at work among them.

Scarcely a paper reaches Victoria from Oregon or Washington states that

docs not contain an account of some brutal murder of whites by the

Indians, or some retaliatory deed of blood by the troops of the United

States. So confirmed, indeed, has their enmity become, that what is

little short of a policy of extermination is being pursued towards the

Aborigines.

But in British Columbia troops have not once been called upon to oppose

the Indians; and men of every class, from the Bishop on his visitation

to the friendless miner, travel among them in confidence and unmolested.

While, therefore, quite prepared to admit that in their government of

the country the Hudson Bay Company have been guilty of sins both of

commission and omission, I cannot, in common justice, forbear from

stating the good they have actually accomplished in British Columbia.

With respect to the routes to British Columbia, there are at present

five open :—

1st. By the Royal West India mail-steamers to Aspinwall, across the

Isthmus of Panama, and thence by American packets to San Francisco and

Victoria.

2nd. By the Cunard steamers to New York, and thence by American steamer

to Aspinwall; the rest of this route being by the same conveyance as the

last.

3rd. Round Cape Horn, or through Magellan Straits, and thence direct to

Victoria by the same ship all the way.

4th. Across the American continent, from Lake Superior or St. Paul’s to

Red River, and thence over the Rocky Mountains. Or, perhaps, it would be

better to say across the continent in British territory, as there are

several ways by which this may be done. And—

5th. Across the continent in American territory to California, and

thence by steamer to Victoria; or by land to Portland, in Oregon, and

from there by steamer to Victoria.

By the first of these routes the total expense of the journey may be

estimated at 90l. for first class, proportionately less of course for

second and third; the time occupied, if there are no delays on the way,

being under six weeks. Adopting this route, the traveller may embark at

Southampton on the 1st or 16th of any month, and Proceed direct to St.

Thomas, a passage of 12 or 14 days. At St. Thomas he takes an

intercolonial steamer, and in four to six days reaches Aspin-wall, the

port on this side of the Isthmus of Panama. Crossing the Isthmus by

rail, in oh hours Panama is reached. Here the great drawback to this

route is often experienced in the fact that there is no certainty of

finding a Pacific steamer ready to sail, and that very often the

traveller has to stop at Panama a week or ten days before one starts.

This delay, of course, adds considerably to the expense of the journey,

to say nothing of Panama being a most unhealthy place to stay in.

Arrangements, however, are said to be making to remedy this

inconvenience.

The passage to San Francisco occupies 14 or 15 days, and on the way the

steamer calls at Acapulco for coal. Arrived at San Francisco a further

delay takes place, and it is sometimes a week or ten days before the

steamer for Victoria leaves. Some arrangement has, I believe, lately

been entered into, however, which has made the line between San

Francisco and Victoria more regular.

By the second route the latter half of the journey is the same as the

first, the difference being that the traveller starts by the Cunard

steamer from Liverpool for New York.

At New York the traveller may have to stay a few days, but this is

better thau waiting at Panama, and then he goes to Aspinwall in a

regular line of American packets: the great advantage of this line being

that it is connected with the Pacific Mail Company’s steamers to San

Francisco, and therefore there is no chance of being—unless, indeed, the

Atlantic packet brings more passengers than the Pacific one can carry

away—kept eight or ten days 011 the Isthmus.

The third route is, by the old way, round Cape Horn, or through the

Straits of Magellan. The drawback to this is the length of the

sea-voyage, which may be said to average five months, although it has

been done in four. The Hudson Bay barque, ‘Princess Royal,’ has for

years made a yearly trip out and home, leaving England in the autumn,

reaching Victoria in January 01* February, and returning home again by

the end of June. She still bears the palm for quick passages. Captain

Trivett, who has commanded her for years, says his great object always

is to get out well to westward after passing Cape Horn, not caring if he

have to go somewhat to southward in doing so, by which he finds he gains

greatly on those who fear getting too far westward, and hug the coast

rather than stretch far out. His quickest passages have been 118 days

out and 110 days home; his average of five passages out 133 days. This

route is by far the cheapest yet open, and indeed may be said to be the

only one within the reach of the poorer class of emigrants. The cost

varies considerably, but will get cheaper as passengers become more

numerous. The Hudson Bay Company’s charge has always been 70l, for first

class and 30l. for second class. Their charges for freight also have

always been high also, but vessels are constantly advertised to sail by

first-rate firms; and a line of clipper ships of 1200 tons is announced

to carry passengers at more moderate rates.

The fourth way lies across our own part of the continent. This route

must be for some time virtually impassable. The. fate of those emigrants

who, deluded by the misrepresentations of the bubble British Columbian

Overland Transit Company, started to make a supposed easy journey from

St. Paul’s across the Rocky Mountains, must still be fresh in the

recollection of my readers. The inducements held out by the so-called

Company, calculated as they undoubtedly were to deceive the public

generally, could impose upon no one who had any practical experience of

the country. For instance, one of their statements was, that above 1000

carts travelled annually along the line they proposed to follow. The

impression conveyed by this is that these carts crossed the Rocky

Mountains into British Columbia by the route proposed to be taken by the

Company; whereas the truth is, that they simply trade to the Red River

and the Saskatchewan country, and no further. That a waggon-road will

some day be carried over the passes of the Rocky Mountains that lie

beyond the Red River settlement, and between that point and British

Columbia, I have no doubt. It may be, indeed, that before very long the

whistle of the locomotive will be heard among them. But that as yet they

are impassable for waggons, and that they present great, and at times

almost insurmountable, difficulty to all save the experienced

unincumbered traveller, the following quotations from the reports of

Captains Palliser and Blakiston and Dr. Hector will, I think, be found

to contain conclusive proof.

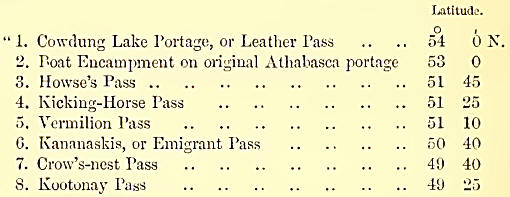

It will assist the reader in forming a judgment upon this matter if I

first give, from the report of Captain Blakiston, an account of the

passes of the Rocky Mountains by which British Columbia may be reached.

“In anticipation,” writes Captain Blakiston, “of the establishment of a

continuous route through British North America, it is proper here to

refer to the passes of the Rocky Mountains north of latitude 49, or, in

other words, in British territory. There are many points at which the

chain of these mountains can be traversed; but omitting for the present

that known as ‘ Peel’s River Pass,’ within the Arctic circle, and that

from Fraser Lake to Pelly

Banks, at the head-waters of the Youkon in latitude 62°, as well as one

from Cease’s House to Stickeen, and others only known to the hardy

fur-traders of the far north, we come to three: one of which crosses

from the Findlay branch of the Peace River to Babine River, the northern

boundary of the province of Columbia; while the other two, at the very

headwaters of Peace River, in latitude 55° north, connect with Fraser

River at its most northern bend, one of which was described, as long ago

as 1793, by that intrepid traveller, Sir Alexander Mackenzie. The

connection with these being, however, by water, and rather far north on

the east side, 1 shall pass on to enumerate the known passes more to the

southward, and which may be called the passes to British Columbia. In

commencing with the North, they stand thus:—

The first of these

connects the head-waters of Athabasca River with the great fork of the

Fraser, and has never been used except as a portage between these two

rivers.

“2. The second is that which, until the last few years, was used

regularly by the Hudson Bay Company for the conveyance of a few furs, as

well as despatches and servants, from the east side to the Pacific, by

the way of the Columbia River, and which, from the ‘ Boat Encampment,’

is navigable for small craft; but this, like the first, has not been

used in connection with any laud-route on the west side.

“3. The third was probably first used by either Thompson or Howse

(author of the Cree grammar), who, following up the north branch of the

Saskatchewan, crossed the watershed of the mountains to the north fork

of the Columbia, and thence to its source, the Columbia Lakes, where,

striking the Kootonay River, he followed it down to the south of 49°

north.

“4. The ‘Kicking-Horse Pass,’ so named by Dr. Hector, crosses the

watershed from near the head-waters of the Dow Diver to those of the

Kootonay, and may be reached by following up either the north or south

branches of the Saskatchewan by land.

“5. While another (see Parliamentary Papers, June 1859), the ‘Vermilion

Pass,’ likewise traversed and laid down by Dr. Hector during the summer

of 1858, occurs also on Bow River so near the last-named one, that it is

unfortunate that the western edge of the mountains was not reached, as

it would then have proved whether these passes can be of value in

connection with a continuous route across the country.

“6. The next pass which enters the mountains in common with the fifth on

Dow Diver, has been named the 'Kananaskis Pass’ (see Parliamentary

Papers, June 1859), and was laid down by latitude and longitude

observations during the summer of 1858 by Captain Palliser. This also

leads to the Kootonay River, passing near the Columbia Lakes. It is

generally supposed that this pass was only discovered last year, but a

description of it is to be found in £ An Overland Journey Round the

World,’ by Sir George Simpson, who, together with a party of emigrants,

50 in number, under the late 5Ir. James Sinclair, passed through, but

not with carts, as had been stated, to the lower part of the Columbia in

1841, besides which it has been used by other travellers. If we are to

consider its western extremity to the south of the Columbia Lakes, it is

a long and indirect route, but as yet it has only been used for

following the valley of the Kootonay, and thence into American

territory. In the event of the country west of the Columbia Lakes

proving suitable for a land-road, this, as well as the previous three,

would prove available for crossing from the Saskatchewan north of

latitude 51°.

“For 100 geographical miles of the mountains south of Bow River no pass

is at present known to exist until we come to the Mocowans, or Belly

River, a tributary of the Saskatchewan, on the branches of winch four

passes enter the mountains—the ‘Crow-nest,’ the ‘Kootonay,’ the

‘Boundary,’ and the ‘Flathead.’

“7. Of the first of these, we know only that its eastern entrance is on

the river of the same name, and that it emerges in the vicinity of the

Steeples, or Mount Deception, while neither of the two last are entirely

in British territory— hence the name of ‘Boundary Pass' for that which

has its culminating point north of 49°.

“8. The ‘Kootonay Pass,’ is the most southern, and, of those yet known,

by far the shortest in British territory.

“These passes, of which the altitudes are known, do not differ greatly;

and I refrain from commenting on their relative merits, because before

any particular one can he selected for the construction of a road, the

easiest land-route from Hope and the western bend of the Fraser River

should be ascertained, which, considering the distance, would be no very

great undertaking. In conclusion, I would only remark, that at present

no pass in British territory is practicable for wheeled-carriages.”

It should be remembered that Captain Blakiston wrote this before an

overland route was thought of. But he has since told me, that during his

explorations he came upon the remains of the waggons of Mr. Sinclair’s

party upon this side of the mountains, the idea of transporting them

farther having been abandoned at that spot.

Dr. Hector, t he geologist accompanying Captain Palliser’s expedition,

upon reaching the Rocky Mountain house, in the most northerly of the

passes enumerated above, writes of it thus: “The mountain-house is at a

distance of not less than 100 miles from the main chain of the Rocky

Mountains, which are nevertheless distinctly seen from it as a chain of

snow-clad peaks. The principal chain is, however, screened by a nearer

range, distant about 45 miles......I made an attempt to reach this near

range, but failed in forcing a road through the dense pine-wood with

which the whole country is covered.’"

Of the Kananaskis Pass, the sixth of the above list, Captain Palliser

writes thus: “On the 18th of August I started to seek for the new pass

across the Rocky Mountains, proceeding up the north side of the

Saskatchewan or Bow River, passing the mouth of the Kananaskis River;

five miles higher lip we crossed the Bow River, and entered a ravine. We

fell upon Kananaskis River, and travelled up in a southwesterly

direction, and the following day reached the Kananaskis Prairie, known

to the Indians as the place ‘where Kananaskis was skinned but not

killed.’ On the 21st we passed two lakes about two miles long and one

wide. We continued our course, winding through this gorge in the

mountains among cliffs of a tremendous height, yet our onward progress

was not impeded by obstacles of any consequence; the only difficulty we

experienced was occasioned by quantities of fallen timber caused by

fires......On the 22nd August we reached the height of land between the

waters of Kananaskis River and a new river, a tributary of the Kootonay

River. Our height above Bow Fort was now 1885 feet, or 5985 feet above

the sea. Next morning we commenced our descent, and for the first time

were obliged to get off and walk, leading our horses down a precipitous

slope of 960 feet over loose angular fragments of rock. This portion of

our route continued for several days through dense masses of fallen

timber, destroyed by fire, where our progress was very slow—NOT owing to

any difficulty of the mountains, but on account of the fallen timber,

which we had first to climb over and then to chop through to enable our

horses to step or jump over it. We continued at this work from daybreak

till night, and even by moonlight, and reached the Columbia Portage on

the 27tli of August.

“On September the 6th I started to recross these mountains by the

Kootonay Pass (the eighth upon the above list). This is frequently used,

but not the general pass of the Kootonay Indians, who have a preferable

one in American territory.

“On the 7th of September we passed the height of land—a formidable

ascent, where we had to walk and lead the horses for two hours. This is

the height of land which constitutes the watershed. We encamped for the

night in a small prairie after making a considerable descent.

“On the 8th of September our course continued through woods and swamps,

for about 15 miles, till we reached another ascent. This was also a

severe ascent, though not so formidable as that of the day previous; we

reached its summit about four o’clock through a severe snow-storm (this

in September), the snow falling so fast as to make me very apprehensive

of losing the track. We descended that evening, and camped on the

eastern side, and next day arrived at the eastern extremity of the pass.

I regret that I cannot give the altitudes of this pass, as our barometer

was broken by one of the horses. It is, however, far from being so

favourable as the more northern, by which I entered on Kananaskis River,

which has but one obstacle, in the height of land, to overcome, and

where the whole line is free from swamps and marshes.”

Dr. Hector, accompanying the same expedition, in speaking of the

Vermilion Pass (the fifth upon the list), says of it: “On the 20th I

crossed Bow River without swimming the horses or unloading the packs,

and, after six hours’ march through thick woods, reached the height of

land the same afternoon. The ascent to the watershed from the

Saskatchewan is hardly perceptible to the traveller who is prepared for

a tremendous climb, by which to reach the dividing ridge of the Rocky

Mountains; and no labour would be required, except that of hewing

timber, to construct an easy road for carts, by which it might be

attained.”

Of the Beaver or Kicking-Horse Pass (fourth upon our list), he says:

“The bottom of the valley (that of the Koutanay River) is occupied by so

much morass, that we were obliged to keep along the slope, although the

fallen timber rendered it very tedious work, and severe for our poor

horses, that now had their legs covered with cuts and bruises.

On the 31st of August we struck the valley of the Kicking-Horse River,

travelling as fast as we could get our jaded horses to go and as I could

bear the motion [he had been badly kicked by a horse]. On the 2nd Sept.

we reached the height of land. In doing so we ascended 2021 feet. Unlike

the Vermilion River, the Kicking-Horge River, although rapid, descends

more by a succession of falls than by a gradual slope. Just before we

attained the height of land, ive ascended more than 1000 feet in about a

mile, down which the stream leaps in a succession of cascades.”

I cannot do better than conclude the consideration of this question of

an overland passage to British Columbia with the following extract from

the Report of Captain Palliser to the Secretary of State for the

Colonies, in 1859

“In answer to the third query contained in your Lordship’s letter, viz.,

‘What means of access exist for British immigrants to reach this

settlement?’ I think there are no means to be recommended save those via

the United States. The direct route from England via York Factory

(Hudson’s Bay), and also that from Canada via Lake Superior, are too

tedious, difficult, and expensive for the generality of settlers. The

manner in which natural obstacles have isolated the country from all

other British possessions in the East is a matter of considerable

weight; indeed it is the obstacle of the country, and one, I fear,

almost beyond the remedies of art. The egress and ingress to the

settlement from the east is obviously by the Bed Biver valley and

through the States.”

Further on the same subject Captain Blakiston writes: “In answer to the

fourth query contained in your Lordship’s letter, viz., ‘Whether,

judging from the explorations you have already made, the country

presents such facilities for the construction of a railway as would at

some period, though possibly a remote one, encourage Her Majesty’s

Government in the belief that such an undertaking, between the Atlantic

and Pacific Oceans, could ever be accomplished?’ I have no hesitation in

saying that no obstacles exist to the construction of a railway from Red

River to the eastern base of the Rocky Mountains; and probably the best

route would be found in the neighbourhood of the south branch of the

Saskatchewan. An amount of capital very small in proportion to the

territory to be crossed would be sufficient to accomplish the

undertaking so far; but the continuation of a railway across the Rocky

Mountains would doubtless require a considerable outlay.

“In my letter to Her Majesty’s Government, dated 7th Oct., 1858, I have

referred to two passes examined by myself and Mr. Sullivan, my

secretary, both of which I found practicable for horses right across the

chain of the Rocky Mountains to the Columbia River, and that a small

outlay would render the more northern one practicable for carts, and

even waggons.

“On the return of Dr. Hector from his branch expedition, I found he had

also crossed the mountains as far as the valley of the Columbia River,

by the Vermilion Pass, which leaves the valley of the Bow River nearer

to its source than the pass I had myself traversed. In that pass he had

observed a peculiarity which distinguishes it from the others we had

examined, viz., the absence of any abrupt step at the commencement of

the descent to the west, both ascent and descent being gradual. This,

combined with the low altitude of the greatest elevation passed over,

led him to report very favourably upon the facilities of this pass for

the clearing of a waggon-road; and even that the project of a railroad

by this route across the Rocky Mountains might be reasonably

entertained.”

Before taking leave of this subject, I think it but right to correct

another impression which appears likely to mislead the public. This is,

that the quantity of buffalo on the route proposed to be taken by the

bubble Overland Transit Company is so great as to render it impossible

for a man with a gun in his hand to starve. Now, although enormous herds

of buffaloes may be met with indeed Captain Palliser writes of them,

“The whole region as far as the eye could reach was covered with

buffaloes in bands varying from hundreds to thousands”—yet it is quite

possible for the traveller to die of slow starvation and exhaustion

without seeing one. Dr. Rae, the eminent Arctic traveller, informed me

that he spent three weeks in these plains with a party of gentlemen, and

that during that time they saw nothing larger than a beaver, and only

shot two. martens!

Again we have seen that Dr. Hector was glad to travel 21 out of 24 hours

for want of food; and in a letter of Captain Falliser, written in the

midsummer of 1858, he says: “On my arrival at the Bow Fort, I found my

hunters waiting for me. They had been out in every direction, but could

not fall in with buffalo. They had also found elk and deer very scarce.”

In the same letter we also find him writing: “Owing to the absence of

buffalo during the winter, my hunters, as well as those belonging to the

Fort, have had to go to great distances in order to get meat, which they

obtained in such small quantities, that the Hudson Bay Company’s officer

in charge of this post was obliged to scatter the men, with their

families, all over the plains in search of food. Even Dr. Hector and Mr.

Sullivan were obliged to leave this post and go to Forts Pitt and

Edmonton in order to lessen the consumption of meat, of which the supply

there was quite inadequate. Fortunately, however, the winter has been an

unusually mild one, otherwise the consequences might have been very

serious indeed.”

Speaking of the mountains on the west side, Captain Palliser also

remarks: “The fact is, the knowledge the Indians possess of the

mountains is very small; and even among those said to 'know the

mountains,’ their knowledge is very limited indeed. This is easily

accounted for by the scarcity of the game, which offers no inducement

for the Indians to go there.”

Dr. Hector also writes: “While traversing this valley, since coming on

the Kootanie River, we have had no trail to follow, and it did not seem

to have been frequented by Indians for years. This makes the absence of

game all the more extraordinary. The only animal which seemed to occur

at all was the panther. The Indians saw one; and in the evening we heard

them calling, as they skirted round our camp, attracted by the smell.”

To this testimony of others, I may add my own experience. I have

travelled 600 miles in British Columbia without seeing anything larger

than grouse, or having the chance of more than half-a-dozen shots at

them. I have also had occasion to speak of death by starvation among the

Indians. This has been by no means uncommon of late, since they have

neglected the culture of their land for the more alluring search after

gold. If, then, the native of these plains finds it impossible to

support life upon the wild animals frequenting it, what chance, under

similar circumstances, could the artisan or the peasant, fresh from the

loom or plough, be expected to have?

The last of the routes which I have to consider is that across the

continent in American territory. A way between New York and San

Francisco has been for some time open, and so regular and speedy is the

transmission of mails by it, that the American postal subsidy has been

taken away from the Panama Steam Company, and given to the Overland. The

traveller by this route proceeds by rail to St. Louis on the border of

Illinois and Missouri. Thence by stage across Missouri to St. Joseph, by

the Missouri River to Omaha city, and from there across Nebraska and

Utah to the Great Salt Lake city. From Utah the route passes southward

of the Humboldt Mountains to Carson city and into California. A

telegraph now runs along the whole of this line, while a stage-coach

goes three times and the pony-express twice a week—the latter making the

journey in about seventeen days. The whole distance from New York to San

Francisco is about 8000 miles, of which 900 are travelled over by rail.

From San Francisco the traveller can reach his destination by land

through California and Oregon to Portland, and thence by steamer to

Victoria: or via the Columbia River to Walla-Walla and thence through

Okanagan across to the Thompson River, and so direct to the mines. This

route across the continent is considered pretty safe, and I know a lady

who crossed by it; but the mails are sometimes waylaid by Indians, and

the passengers murdered or ill-treated.

Before treating of the mineral resources of British Columbia, I wall

endeavour to describe its physical aspect. The coast of British Columbia

is fringed with dense forest, sometimes growing on low ground, but

generally covering mountain-ridges of all shapes, which terminate in

numbers of irregular peaks shooting up in every possible form and in

heights varying from 1000 to 10,000 feet. All these ridges and peaks

have the same general appearance, being composed of trappean or granitic

rocks and covered with pine-trees to the height of 3000 or 4000 feet,

and sometimes higher. Here and there the constant fires caused by the

carelessness of the Indians have stripped the branches from all the

trees on a hill-side, leaving nothing but scorched trunks standing on

the blackened rock; while in other places they appear stripped in the

same way from top to bottom of a mountain, the whiteness of the trunk,

however, forbidding the notion of fire. The reason of this phenomenon,

which was of frequent occurrence in the inlets, caused us much

speculation. The conclusion arrived at was, that it was caused by a

slide of frozen snow from the mountain’s summit. These mountain-ridges

are divided at intervals all along the coast by the long inlets of which

I have before spoken.

Behind all these minor ranges and inland of the heads of the inlets, the

Cascade Range rims nearly parallel with the coast, and at a distance of

60 to 100 miles from it, forming a barrier but too effectual to shut out

intruders into the Eldorado that lies beyond it. The highest peak of

this range is Mount Baker, situated hi latitude 48° 44' N. and

consequently upon American territory. Its height is 10,700 feet, and it

forms a prominent feature in the view from any part of the Strait of

Fuca or Gulf of Georgia. Though, as I have mentioned when describing the

inlets of the coast, there is usually a valley, sometimes of

considerable extent, at the head of these sea-arms, the Cascade

Mountains, as far as explorations have yet been carried, appear always

to bar approach to the country beyond. Sometimes they recede from the

coast so much that it is possible to steam 40 or 50 miles inland; but in

time the mountains are sure to be found closing in and barring farther

progress. The valley of the Fraser River forms the single exception to

this rule. Here the river has certainly mastered the rocks, and,

attacking them from the rear, cut itself a devious way to the sea. But

it has done no more, the rocks so closing in upon its course that, as in

the canons I have described, there is hardly footing left for a goat

along the high precipitous banks.

These coast-mountains have as yet been imperfectly examined, and little

therefore is known of their geological formation or mineral resources.

Hr. Wood, who, it will be remembered, accompanied me on my excursion

inland from Jervis Inlet, says of those we passed on that occasion, “On

the right side of the upper arm of Jervis Inlet the mountains, against

whose sides the sea washes, give indications of being composed of

porphyritic granite; the granite rocks generally are deeply imbued with

copper oxides; their veins of white quartz are frequently seen

intersecting the granite. The rocks forming the sides of the second

inlet, some six or eight miles distant, are more rugged and precipitous,

and consist generally of a strongly micaceous quartzose granite. A

mountain-stream which we crossed, presented in the granite and trap

boulders, which formed its bed, singularly rich specimens of iron

pyrites without any observable indications of other metals. Upon another

mountainous stream which we crossed, I saw the largest boulder of quartz

(transported) I ever witnessed; it must have been four or five tons’

weight, and was deeply stained on one side with oxides of iron.” During

this journey, I perceived indications of nothing but trap and granite,

with here and there thin veins of quartz. Indeed, I may say, that all

the inlets surveyed by the ‘Plumper’ presented the same geological

characteristics. Texhada Island, which lies off the entrance of Jervis

Inlet, is, however, an exception: nearly the whole of the northern end

being limestone, mostly blue, but some white and comparatively soft; the

blue being very hard. I found a few small outcrops of limestone in the

entrance of Jervis Inlet afterwards, but they were only thin veins,

round which the igneous rock had hardened. Clay-slate frequently occurs

in the inlets, but usually in very small outcrops. I have remarked its

occurrence also in the canons of the Fraser River, and Lieut. Palmer,

ILL. when in the same range (Cascade) on the Harrison-Lilloett route,

says, “From the cursory view I was enabled to take of the general

geological character of the country, trappean rocks appear to prevail,

consisting principally of greenstone, dense clay-slate (here and there

presenting a laminated structure), and compact hornblende. The exposed

surfaces of the rocks are generally covered with felspar, and are

occasionally stained red with iron, forming an agreeable contrast in the

landscape. Quartz-veins permeate the clay-slate in many places, of an

average thickness of one to twelve inches; the formation, in fact, would

suggest the high probability of metalliferous deposits. The mountains

rise bold, rugged, and abrupt, with occasional benches on their sides,

on which are found quantities of worn rounded boulders, principally of

coarse-grained granite, occasionally porphyritic. The granite contains

golden-coloured and black mica in large quantities. The crystals of

felspar in the porphyritic granite are very numerous, but small. The

soil appears in many places to have been formed by the decomposition of

granite, it being light and sandy and containing much mica.

“Below the soil is very generally found a white compact mass, very hard

and approaching to a conglomerate, containing pebbles of every

description in a matrix of decomposed clay-slate. Lime seems wanting

even in the conglomerate, and I saw no traces of limestone or sandstone

all along the route, though I understand there is plenty of the former

at Pavilion.”

Along the coast, between Jervis Inlet and Desolation Sound, the

appearance of the rocks changes somewhat, and quartz and slate

predominate.

Speaking of Desolation Sound, Mr. Downie says, “This is the first time I

have seen pure veins of sulphuret of iron, which looks very much like

silver. I came across a number of seams of the same kind; it lies in

quartz, the same as gold. I have no idea that the gold is confined to

the Fraser River alone; and if it can only be found from the seaboard,

or on the rivers at the head of some of these inlets, the country will

soon be prospected.” At the head of the same inlet, he says, “ I have

seen more black sand here in half a day than I did in California in nine

years; it looks clear and bright, as if it came from quartz.” f Seeing

it was out of the question to proceed farther, we put back, and came

down along shore, breaking and trying the rocks, finding much iron

pyrites and sulphuret of iron, but no gold.

In Knight’s Inlet I have mentioned plumbago as having been found; and on

Queen Charlotte’s Island (which may be regarded, in common with the rest

of these islands, as chips off the coast), gold-bearing quartz and coal.

Of the geological features of the interior little is yet known. Wherever

I have been, the same trappean rocks predominate as on the coast, except

at and around Pavilion, 220 miles up the Fraser, where limestone occurs

in large quantities. In the Cariboo district Mr. Hind, the Gold

Commissioner, says lie has observed “masses of quartz;” and when

travelling near the Antler Creek, in the valley of which some of the

richest diggings occur, he says, “The streams I passed were very

numerous; and where it was possible, from the falling in of the ice and

snow, to observe their beds, I noticed the same characteristics of large

quartz boulders and a kind of slate-rock, covered with red gravel, said

to bear a close resemblance to the rich auriferous beds of the streams

of the southern mines of California.

Of the Semilkameen district, in the southern part of the colony,

Lieutenant Palmer, R.E., in his Report quoted before, writes:—“The

geological character of the several districts (Fort Hope and Fort

Colville) is throughout very uniform, the rocks belonging principally to

the igneous and metamorphic series. The bulk of Hanson Mountain appears

to be granite, tipped with slate; here and there presenting particles of

white indurated clay, found, on examination, to contain fragments of

white quartz.

“This formation may be said to consist of granite, with its felspar

decomposed and reduced to a state of indurated clay; it extends to the

dividing ridge of the Cascades, and partly into the valley of the

Tulameen. In the latter valley may be seen vast masses of white quartz;

in all probability the exposed face of the rock, which, with granite,

constitutes a large portion of the district, extending into the

Semilkameen valley.

“On approaching the summit of the Tulameen range, the quartz partially

disappears, and is replaced by a species of variegated sandstone, in

which traces of iron occur. To what extent the sandstone prevailed I had

no opportunity of judging, the weather being snowy while I was there,

and the rocks, as a rule, imbedded in peaty turf.

“As we leave the Tulameen Mountains, and descend into the valley below,

indurated clay appears to predominate to a considerable extent. This

clay varies in character as we approach the Vermilion Forks; a portion I

noticed near that point being a white silicate of alumina mixed with

sand. On one specimen which I picked up were the fossil remains of the

leaves of the hemlock.

“Further down, in the Semilkameen valley, the clay acquires a slaty

texture, and becomes stained with iron, to a greater or less extent.

Blue clay also exists, only, however, in small quantities.

“The mountains bordering the Semilkameen consist chiefly of granite,

greenstone, and quartz, capped with blue and browui clay-slate. The beds

of both the Tulameen and Semilkameen are covered with boulders of

granite, of every description and colour; of greenstone and of trap, and

vary in form and size.

“Boulders of the same character prevail on the river-bottoms, to a

greater or less extent. Like that of most of the other explored parts of

British Columbia, the geological character of this region appears to

indicate the high probability of auriferous deposits. In the lower

portion of the Semilkameen, and near the ‘Big Bend,’ gold was discovered

shortly after I passed through, by some of the men attached to the

United States Boundary Commission. Beport pronounced the discovery a

valuable one, as much as 40 dollars to the hand being taken out in three

hours, without proper mining-tools; but I cannot speak positively as to

the truth of this statement, neither could I discover whether the place

spoken of was in British or American possessions. Probability would

suggest the former. Beyond Osoyoos Lake I did not deem it necessary to

pay much attention to the geological character of the country, the route

lying almost entirely in American possessions. Suffice it to say that

but few features of interest presented themselves, and that in no place

did I see any sign of stratified rocks.”

The only part of the country which can be said to have been geologically

surveyed, is the neighbourhood of the Harrison Lake and the portage

which lies between Port Douglas and Lilloett. In the summer of 1860, Dr.

Forbes, of H.M.S. ‘Topaze,’ undertook this service; and his Report

contains, among other things, much valuable information as to the

existence of silver there. Of the Harrison Lake, he says: “At the mouth

of the stream (on the east side of the lake) and extending on both sides

along the shore of the lake, were water-worn boulders of granitic and

quartzose rocks; gneiss, with garnets; mica-schist, with garnets; pieces

of good roofing-slate, together with masses of a pure white quartz,

containing excellent indications of metal. The mountain, the top of

which is somewhat rounded in its outline, having a flat surface to the

westward, and a remarkable pinnacle or finger-like rock at its immediate

base, is composed of trap; having resting upon it, and tilted at a high

angle, micaceous, talcose, and horn-blendic schists, all highly charged

with iron, the oxidation of which has produced disintegration of these

rocks. At a point 500 yards from the mouth of the stream, on its proper

right bank, a mass of trachytic rock has been erupted, shattering the

surrounding rocks, itself much shaken and shattered; great masses,

dislodged by weather and other causes, having slipped and rolled to the

bottom of the ravine.

“In this rock, of volcanic origin, was found a mass of quartz, of a

beautiful white colour, containing good indications of silver and

copper; which indications proved true, for, on assaying a specimen by

the reducing process, a globule of each of these metals showed itself.

The mass or vein of quartz dips northerly, beneath the overlying

trachytic rocks. It is wedge-shaped, the thickness increasing with the

depth. From it, in all directions, radiate veins of quartz; which,

guarded on each side by a fissile rock, of a French-grey colour,

permeate the mass of trachyte in all directions. Those only which run

north and south are metalliferous; the east and west veins, or cross

courses, are barren.

. . . . I proceeded to examine the veins, seriatim, as they radiated

from the great central mass. Rising in a northwesterly direction is a

quartz-vein, running through or along with the fissile rock above

alluded to, containing ores of silver; and to the right, having the same

north-west and south-east direction, about 200 yards above the ‘mother

vein,’ a quartz-vein shows itself in the broken precipitous face of the

continuing trachytic rock. It runs between two great bands of

French-grey coloured rock, separated from it by masses of partially

decomposed pyrites; which besides, in a band about three inches in

thickness, accompanies the quartz-vein throughout its course.

“Besides these masses and bands of iron pyrites, masses of a dark-green

chlorite rock occur; and nodules containing sulpkuret of silver are

clearly discernible, both in the veir itself and the rock through which

it passes.

“Following the ravine, and at the same time ascending, 1 found, at an

elevation of about 600 or 700 feet, another quartz-vein, of the same

character, dipping in the same direction, and belonging to the same

system; and, from the numerous angular fragments of quartz and quartzose

rocks everywhere scattered about, I believe there are numerous other

veins, which I had not time to look for or explore. I worked into the

quartz-matrix and its ramifying veins, and satisfied myself of the

existence of silver at this spot, which, however, will require somewhat

extensive mining-operations to procure in paying quantities. The

geological character of this locality affords a good type of the general

formation of the whole eastern side of the lake, and may here be briefly

described as a region of primary, metamorphic, and volcanic rocks,

crossed and recrossed by trappean dykes and veins, and seams of

metalliferous quartz and quartzose rocks. The primary and igneous rocks,

which form the central axis of the mountain-range, have on then* flanks

transverse ridges and spurs of trappean rock, bedded and jointed;

resting on which, at various angles, lie the metamorphic schistose

rocks, which, again broken through, disturbed, and shattered by

successive intrusions of volcanic rock, have in many instances undergone

a second metamorphosis, and show an amorphous, crystalline structure,

accompanied by segregation of metal into the permeating veins.”

Speaking of the country that lies farther up the lake, he says: “The

great mass of debris in all the slips was composed of plutonic, trappean,

and quartz rocks; all of them full of beautiful groups and strings of

crystals of iron pyrites, both massive and in cubes, and all possessing

good indications of the proximity of valuable mineral.”

Of the road between Douglas and Lilloett, he observes: “The

argentiferous rock is of a pale-blue colour, with masses and strings of

quartz running through it. Sulphuret of silver, argentiferous pyrites,

and some specks of gold, were to be seen along with iron pyrites in

cubes and masses. The vein runs through trap, which, when in contact

with the vein, is of a trachytic character. Great volcanic disturbances

have taken place, numerous faults existing in the trappean range, which

runs in parallel ridges north and south, slips and slides having taken

place in the planes of bedding; and the bluff in which this

metalliferous rock is found appears to be the result of a great slip

from the boundary range of the valley on its eastern side.” Of the whole

way to the Hot Springs on the Douglas road, 23 miles from Port Douglas,

lie says: “The geological formation is trap of various characters in

reference to its crystallization and bedding; in some cases both these

characteristics very perfect, in others less so. Metamorphic rock,

altered and disturbed by its intrusion, permeating quartzose veins, in

some cases metalliferous, in others not so, run through the whole

formation. Near the Hot Springs an erupted granite-rock, having a highly

crystalline trap on both flanks, occurs, which extending eastward has

relation to the granitic rock developed in the argentiferous formation

at Fort Hope, if indeed it be not the same.

“Trap rises in lofty precipices on the western side of the river (Lilloett

River), and continues on the east, resting on a rocky range of white-coloured

stone, which, on examination, proved to be a silicious rock, containing

a few indications of copper. The formation on the western side of the

river indicates that these veins (quartz) pass along a ravine which dips

to the river-bed, under which they pass to rise again. The most

promising vein is a quartzose mass, 6 feet in thickness, bedded in and

running along with a silicious rock, having masses and fragments of

talcose schist in the immediate vicinity. The quartz contained strings

of sulphuret of silver, and is, I believe, the outcrop of a valuable

mine.”

Summing up these indications, Dr. Forbes remarks : “ The elevation of

all these ranges is due to the action of volcanic forces, causing, in

the first place, in this north-west and south-east line, a slow and

gradual upheaval of the primary and igneous rocks composing the crust of

the earth. Then, as these forces increased in intensity, upheavals and

disturbances of the mountain masses occurred, both generally and

locally, until the geographical features of the country assumed their

present aspect, viz. great mountain-chains, running north-west and

south-east, having, at right-angles to their axis of elevation, trappean

rocks running east and west in transverse spurs and ridges. Resting on

these spurs, tilted by them at various angles, are detached and broken

masses of metamorphic rock of various kinds, such as clay-slate,

micaceous, hornblendic, talcose, and chlorite schists, all permeated by

dykes and veins of erupted rock, which, in many instances, have changed

the metamorphic rocks at the points of contact into 'amorphous

semi-crystalline masses.”

I have before mentioned the discovery of coal at other places than

Nanaimo, where it is now worked. All the north end of Vancouver Island,

indeed, contains coal-measures, and some quantity has been taken out a

little way to the northward of Fort Rupert. The specimens we had on

board when we were there were considered quite equal to Nanaimo coal,

and the Indians brought some from the mainland opposite, which was also

very good. In 1859, coal was found in Coal Harbour, Burrard Inlet, and

we took six bags from the outcrop there, upon the quality of which the

engineer reported very favourably. It is no exaggeration, indeed, to say

that coal exists all along the shores of both colonies; and, when any of

the inlets become of sufficient importance to make the work

remunerative, there is no doubt it will be found in working position and

sufficient quantities. At Nanaimo the seams have lately been tested by

bores with the most satisfactory result; and, quite lately, it has been

found close to the water’s edge on one of the islands 40 or 50 miles

north of that place. In the beginning of last year, Mr. Nicol, the

manager of the coal-mines at Nanaimo writes: “We have got the coal in a

bore nearly 5 feet thick. I have now fully proved 1,000,000 tons. A

shaft 50 or 52 fathoms deep will reach the coal; dip, 1 in 7; a very

good working seam. I have no doubt there is another seam underlying this

one, of an inexhaustible extent. I have got the outcrop inland, and,

from dip to strike, I am sure it is about 30 fathoms below; so that by

continuing the same shaft, if necessary, another larger seam containing

millions will be arrived at; but the first seam will last my life, even

with very large works. With about 5000/. or 8000/. I could get along

well, and start a business doing from 60,000 to 100,000 tons a year. The

price is 25s. to 28s. alongside the ship.”

It will give a better idea of the comparative cheapness of this coal if

I say that at San Francisco the Nanaimo coal sells from 12 to 15 dollars

(21. 8s. to 3/.), while the cheapest good English coal cost, when I was

there, 20 dollars, or 4/. a ton, and it had been worth more than that.

At Panama the U. S. frigate ‘ Saranac ’ had to lay in some coal, and

paid 35 dollars (7/.) a ton for it. I happened to be in San Francisco

later, when the same vessel came there to be docked. The coal was taken

out to lighten the ship, and it was so bad and dusty that it was not

considered worth taking on board again.

Mr. Bauermann, the geologist of the Boundary Expedition, says of the

Nanaimo coal: “Two seams of coal, averaging 6 or 8 feet each in

thickness, occur in these beds, and are extensively worked for the

supply of the steamers running between Victoria and Fraser River. The

coal is a soft black lignite, of a dull earthy fracture, interspersed

with small lenticular bands of bright crystalline coal, and resembles

some of the duller varieties of coal produced in the South Derbyshire

and other central coalfields in England.

“In some places it exhibits the peculiar jointed structure, causing it

to split into long prisms, observable in the brown coal of Bohemia. For

economic purposes these beds are very valuable. The coal burns freely,

and yields a light pulverescent ash, giving a very small amount of slag

and clinker.”

These beds were first brought to notice in 1850 by the Indians bringing

some coal to one of the Hudson Bay Company’s agents. This was found on

Newcastle Island, in the harbour, and they said they had seen the same

on the mainland. It proved to come from the outcrop of the Douglas seam,

which was afterwards found to cross the harbour to the island mentioned,

where some of the best coal is now taken out. Since its discovery it has

been worked by a Company known as the Nanaimo Coal Company, which,

however, was really under the management of the Hudson Bay Company’s

officials. Quite recently, however, a new Company has been formed, who

have purchased good-will, stock and fixtures. It is to be hoped that

better fortune will attend this enterprise. Strange enough, whatever

else than furs the Hudson Bay Company meddle with appears almost

invariably to prove a failure. They mismanaged affairs at Nanaimo,

certainly. Good and expensive machinery was sent and fixed, but

sufficient capital to work it was not forthcoming; so that the managers

were impeded at the outset and, not enabled to develop the resources of

the place.

The greatest objection to the Nanaimo coal is its dust and dirt. It

burns well, however, and HAIS. ‘Satellite’ was able to get better steam

with it than with any other coal. We used it constantly in the ‘Plumper’

for four years without having any other reason of complaint than the

dirt arising from it. One of the originators of the new Company which

has taken these mines assures me that one valuable quality of this coal

is its adaptability for making gas. At San Francisco and in Oregon it is

preferred for this purpose to any other coal, on account of its being so

highly bituminous. It may be remarked, that the deeper the workings at

Nanaimo are earned the better the quality of the coal becomes.

The natural resources of British Columbia, however, independently of its

mineral wealth, are such as to make it well worthy of the consideration

of agricultural settlers.

After the Cascade Range is passed, or from Lytton upwards, the country

assumes an entirely different aspect from that of the coast. The dense

pine-forests cease, and the land becomes open, clear, and in the spring

and summer, time covered with bunch-grass, which affords excellent

grazing for cattle. Although this country may rightly be called open,

that word should not be understood in the sense in which an Australian

settler, for instance, would accept it. There are no enormous prairies

here, as there, without a hill or wood to break the monotony of the

scene far as the eye can reach. It is rather what the Californians term

“rolling country,” broken up into pleasant valleys and sheltered by

mountain-ridges of various height. These hills are usually well clothed

with timber, but with little, if any, undergrowth. The valleys are

generally clear of wood, except along the banks of the streams which

traverse them, on which there is ordinarily a sufficiency of willow,

alder, &c., to form a shade for cattle. The timber upon the hills is

very light, compared with its growth upon the coast; indeed, there is

nothing more than the settler requires for building, fuel, and fencing.

Several farms are now established in different parts of the country. I

have mentioned one at Pavilion in the account of my journey there, and

since there have been greater facilities for obtaining land many others

have, I believe, been started. Mr. McLean, who was in charge of Fort

Kamloops, when I visited it, has since left the Company’s service, and

cultivates a farm near the Chapeau River. He has been many years in the

country, and at Kamloops carried on considerable farming operations on

behalf of the Company. Governor Douglas, speaking of this district, over

which I travelled in 1859, viz. that of the Thompson, Buonaparte, and

Chapeau rivers, says :—

“The district comprehended within those limits is exceedingly beautiful

and picturesque, being composed of a succession of hills and valleys,

lakes and rivers, exhibiting to the traveller accustomed to the endless

forests of the coast districts the unusual and grateful spectacle of

miles of green hills crowning slopes and level meadows, almost without a

bush or tree to obstruct the view, and even to the very hilltops

producing an abundant growth of grass. It is of great value as a grazing

district,—a circumstance which appears to be thoroughly understood and

appreciated by the country packers, who are in the habit of leaving

their mules and horses here when the regular work of packing goods to

the mines is suspended for the winter. The animals, even at that season

are said to improve in condition, though left to seek their own food and

to roam at large over the country: a fact which speaks volumes in favour

of the climate and of the natural pastures. It has certainly never been

my good fortune to visit a country more pleasing to the eye, or

possessing a more healthy and agreeable climate, or a greater extent of

fine pasture-land; and there is no doubt that, with a smaller amount of

labour and outlay than in almost any other colony, the energetic settler

may soon surround himself with all the elements of affluence and

comfort. Notwithstanding these advantages, such have hitherto been the

difficulties of access that the course of regular settlement has hardly

yet commenced.

“A good deal of mining-stock has been brought in for sale, but, with the

exception of eight or ten persons, there are no farmers in the district.

One of those, Mr. McLean, a native of Scotland, and lately of the Hudson

Bay Company’s service, has recently settled in a beautiful spot near the

debouche of the Hat River, and is rapidly bringing his land into

cultivation. He has a great number of horses and cattle of the finest

American breeds; and, from the appearance of the crops, there is every

prospect that his labour and outlay will be well rewarded. He is full of

courage, and as confident as deserving of success. He entertains no

doubt whatever of the capabilities of the soil, which he thinks will,

under proper management, produce any kind of grain or root crops. The

only evil be apprehends is the want of rain, and the consequent droughts

of summer, which has induced him to bring a supply of water from a

neighbouring stream, by which he can at pleasure irrigate the whole of

his fields.”

Again; Mr. Douglas, in speaking of the farm at Pavilion, which I

mentioned in my account of that place, says :—

“I received an equally favourable report from Mr. Reynolds, who

commenced a farm at Pavilion in 1859, and has consequently had the

benefit of two years’ experience. His last crop (1860), besides a

profusion of garden vegetables, consisted of oats, barley, turnips, and

potatoes, and the produce was most abundant. The land under potatoes

yielded 375 bushels to the acre. The turnip-crop was no less prolific;

one of the roots weighed 26 lbs., and swedes of 15 lbs. and 16 lbs. were

commonly met with.4 He could not give the yield of oats and barley, the

greater part having been sold in the sheaf for the mule-trains passing

to and from the mines ; but the crop, as was manifest from the weight

and length of the straw, which attained a height of fully four feet, was

remarkably good. He generally allows his cattle to run at large, and

they do not require to be housed or fed in winter. The cold is never

severe; the greatest depth of snow in 1859 was 12 inches, and the

following winter it did not exceed 6. Ploughing commences about the

middle of March. The summers are generally dry, and Mr. Reynolds is of

opinion that irrigation will be found an indispensable application in

the process of husbandry in this district. In the dry summer of 1859 he

kept water almost constantly running through his fields, but applied it

only twice during the summer of 1860, when the moisture of the

atmosphere proved otherwise sufficient for the crops.”

Although the irrigation spoken of as necessary may appear a great

drawback, it is not so really; for so numerous are the streams all over

the country, and in such a variety of directions do they run, that very

little care will enable a man so to lay out his fields that he may

always have plenty of water at his command. The Governor remarked this.

“The numerous streams,” he says, “which permeate the valleys of this

district afford admirable facilities for inexpensive irrigation. So

bountiful, indeed, has Nature been in this respect, that it is hardly an

exaggeration to say that there is a watercourse or rivulet for every

moderate-sized farm that will be opened in the district.”

I think it will be found, however, that, as civilization advances, as

the hill-tops are denuded of trees, and the soil of the valleys is

broken up, artificial irrigation will not be so necessary as it now is.

Experience elsewhere shows that the climate changes as a country becomes

settled; and already this is felt in other parts of this colony. Last

year the rain fell in the summer time much more abundantly than it had

been known to do before ; while the winter, in which hitherto all the

rain had fallen, was drier. I think that Victoria has seen the last of

the regular wet and dry seasons that used to set in, and that henceforth

there will be rain throughout the year as in England. The rain also

becomes much less partial as settlement progresses. A few years ago we

used to have rain at Victoria when not a drop fell at Esquimalt, three

miles off; and I have seen it rain hard on shore on one side of the

harbour, when there was none falling on the other. This, however, seldom

happens now.

The country lying south-east of the district we have been considering,

is perhaps even richer and more open. I have never visited it myself;

but every one whom I have heard speak of it called it the best

agricultural district in the colony. It is usually called the

Semilkameen country, from the river of that name which runs through it;

and it extends from the Nicola River and head-waters of the Thompson, at

the Shuswap Lake, down by the Okanagan Lake and River to the boundary

line. This region has lately been opened up by a trail cut from Fort

Hope through a gorge in the Cascade range of hills, which at that point

are called Manson Mountains; and thence descending upon the Semilkameen

and Okanagan Rivers. Beneficial as this trail will be to that district,

like most of the mountain-trails of the country, it will only be

available from four to six months of the year from the depth of snow in

the gorge through which it passes.

In September, 1859, Lieutenant Palmer, R.E., was sent to examine this

trail and, the country adjoining it; and although he reports very

favourably on the soil and general capabilities of it, he thinks the

difficulty of obtaining provisions, &c., will deter settlers for some

time. Of the soil he says: “The grass is generally of a good quality,

the prickly-pyar and ground-cactus, the sore enemy to the moccassined

traveller, being the surest indication of an approach to an inferior

quality. Timber is for the most part scarce, but coppices appear at the

sharp bends of the river tolerably well wooded, and abounding in an

underbush of willow and wild cherry, while near the base of the

mountains it exists in quantities easily procurable, and more than

sufficient for the requirements of any settlers who might at some time

populate the district. The soil is somewhat sandy and light, but free

from stones, and generally pronounced excellent for grazing and farming;

and though the drought in summer is great, and irrigation necessary,

many large portions are already well watered by streams from the

mountains, whose fall is so rapid as greatly to facilitate such further

irrigation as might be required. In corroboration of my expressed

opinion relative to the yielding properties of the soil, I may mention

that in spots through which, perchance, some small rivulet or spring

wound its way to the river, wild vegetation was most luxuriant, and

grass, some blades of which I measured out of curiosity, as much as nine

feet high, well rounded and firm, and a quarter of an inch in diameter

at its lower end. The river throughout its course is confined to a

natural bed, the banks being steep enough to prevent inundation during

the freshets (a favourable omen for agriculture), and its margin is

generally fringed with a considerable growth of wood of different

kinds.”

In concluding his report he says: “The present undeveloped state of

British Columbia, and the absence of any good roads of communication

with the interior, would probably render futile the attempt to settle

the Semilkameen and other valleys in the vicinity of the 49th parallel.

Extensive crops, it is true, might probably be raised, but the immigrant

would have to depend for other necessaries of life either on such few as

might from time to time find their way into the country from Washington

territory, or on such as might, during four months in the year, be

obtained from Fort Hope and other points on the Fraser River, and either

of which could not be obtained but at prices too exorbitant for the

pocket of the poor man. It would seem, therefore, that the Buonaparte

and Thompson River valleys are the natural starting-points for

civilization and settlement. Starting from these points, civilization

would gradually creep forward and extend finally to the valleys of the

frontier.”

While quite agreeing with Lieutenant Palmer that the Buonaparte and

Thompson valleys have at present the advantage of the Semilkameen, I

think he overestimates some of the difficulties of settling the latter.

The great advantage possessed by the former is in the fact of their

lying on the road to the richest diggings now worked in the country (Cariboo).

This, of course, enables the farmer to find a near and convenient,

market for his produce; as, for instance, in one of the reports from

which I have quoted, Mr. Reynolds, a farmer there, is said to have sold

all or nearly all his oats and barley in the sheaf to the mule-trains

trading to the mines. Just now the Semilkameen country, in which very

rich diggings were discovered, has been deserted for the superior

attractions of Cariboo; but a lucky find, which is likely to occur at

any time, will bring the miners hurrying back again, to the profit, of

course, of the settlers farming there. In proof of the probability of

this occurring, it may be mentioned that in May 1861, Mr. Cox (the Gold

Commissioner at Rock Creek) reports: “We prospected nine streams, all

tributaries of the lake (Okanagan), and found gold in each, averaging

from thirty to ninety cents a pan.” He then mentions other good

prospects which have not been nude public, “as it would only lead to bad

results just at present. The miners in this (Rock Creek) neighbourhood

would be easily coaxed off, and the mines now in preparatory condition

for being worked, abandoned; improvements going on in buildings or farms

would be checked; town lots would be almost unsaleable; in fact, the

expected revenue receipt would be seriously interfered with.”

As to the necessaries and even the luxuries of life, there is no doubt

that the settlers in the Semilkameen districts could command them

cheaper and more readily than those upon the Upper Fraser, obtaining

them as they might across the boundary from Walla-Walla and Colville

upon the Columbia River. I have before mentioned that this fact of the

Americans carrying on a trade across the frontier was a great cause of

complaint to the British merchants, who, having to take their goods up

the Fraser River, found themselves undersold by their more fortunate

rivals. To remedy this, in December I860, an order was issued

prohibiting the transmission of goods across the frontier except at a

high rate of duty, and then only “pending the completion of the

communications in British Columbia.” This prohibitory proclamation was

issued because when the Governor visited New Westminster in October

1860, “there was much depression in business circles, and a marked

decrease of trade; .... a casualty generally attributed by business men

to the growing overland trade with the possessions of the United States

in Oregon and Washington territory, which now supply, on the southern

frontier of the colony, a large proportion of the bulky articles, such

as provisions and bread-stuffs, consumed in the eastern districts of

British Columbia.” This clearly shows that the southern districts of the

colony can be more easily supplied than any others: while, for

agricultural purposes, the advantages of climate there will be a

consideration of great weight.

In the northern part of the colony, from Alexandria upwards, although

the soil, wherever it has been tried by the Hudson Bay Company’s people,

has been found good, the country is too cold and liable to frost, in the

early summer, to offer the attractions as a producing district possessed

by the country farther south.

Mr. McLean, however, who lived many years at Alexandria, told me that he

had known a bushel of wheat planted there yield forty bushels; but this

was considerably more than an average produce. Of the Upper posts, Mr.

Manson, who was seven years at Fort St. James, told me the soil is good,

but the crops, except barley, are almost always nipped by frost. During

the whole of his residence there, they only got two crops of potatoes.

At Fraser Fort, which is in nearly the same latitude as Fort James, but

considerably to the westward of it, vegetation thrives much better, and

barley, peas, turnips, and potatoes, almost always yield good crops. The

country southward of Fraser Fort and down to the Chilcotin River, I was

told by Mr. McLean, as well as by a settler whom I met at Pavilion,

contained very good farming-land, bnt on most of it there are two or

three feet of snow every winter: so that these regions will not yet vie

with those before spoken of; for at Pavilion, in the northern part of

the Thompson River district, Mr. Reynolds, as I have before mentioned,

said they had only twelve inches of snow in the winter of 1859-60, and

only six inches in 1860-61. Moreover, in the north the cattle must

always be stall-fed in winter.

Of the banks of the Lower Fraser, between the mouth of the river and

Fort Hope, the Governor writes: “The banks of this river are almost

everywhere covered with woods. Varieties of pine, and firs of prodigious

size, and large poplar-trees, predominate. The vine and soft maple, the

mid apple-tree, the white and black thorn, and deciduous bushes in great

variety, form the massive undergrowth. The vegetation is luxuriant,

almost beyond conception, and at this season of the year presents a

peculiarly beautiful appearance. The eye never tires of ranging over the

varied shades of the fresh green foliage, mingling with the clustering

white flowers of the wild apple-tree, now in full blossom and filling

the air with delicious fragrance. As our boat, gliding swiftly over the

surface of the smooth waters, occasionally swept beneath the overhanging