|

I have left myself but

small space or time to speak of that which, is undoubtedly the

mainspring of British Columbia— its immense and apparently inexhaustible

yield of gold. At starting, however, a few remarks upon the various

methods of working mining-claims at the gold-fields may be found of

interest to the general reader.

As a rule, picking up gold is a mere delusive figure of speech. It has

to be dug and worked for hardly, with primitive appliances often ;

sometimes with all the resources of modern mechanism. Before attempting

to describe shortly the various processes of extracting the precious

mineral, I may say that they all require the aid of water and, with rare

exceptions, quicksilver. It is the abundant natural supply of water that

gives British Columbia so great an advantage over California. The

country is, as I have before said, and as a glance at the map will show,

intersected in every direction by streams and rivers, while lakes of

various size abound, the majority of which may be easily adapted to the

purposes of mining. The very height of the hills also, which may be in

other respects a disadvantage, proves in this case of use to the miner

who can divert to his purpose the torrents which course down their

sides. In California the want of water has been much felt, and the

methods resorted to for meeting it illustrate as much as anything else

in that marvellous country the enterprise and spirit of the American

settler. In Grass Valley, Nevada county, one of the richest quartz

districts in California, which I visited in 1860, and where 40

steam-mills were then at work, every drop of water used had to be

brought by “flumes,” from a distance of more than 40 miles!

Quicksilver has as yet always been found to exist in gold countries.

California is abundantly supplied. It has been discovered in several

places in Columbia; but as yet it has been found cheaper to procure it

from California than to work it there.

In 1860 I made the tour of some of the richest diggings in California,

with the view of seeing the various appliances in use there. In

describing these various methods of gold working, I shall have to speak

of several not yet in use in Columbia; some of them, indeed, being but

newly introduced into California.

The first task of the miner attracted to a new gold country or district,

by the report of its wealth, is “prospecting.” For this purpose every

miner, however light his equipment may otherwise be, carries with him a

“pan” and a small quantity of quicksilver; the latter to be used only

where the gold is very fine. Very little experience enables a miner to

detect that “colour” of the earth which indicates the presence of the

metallic sand in which gold is found. Wherever, as he travels through

the new country, he sees this, he stops at once to wash a pan of dirt,

and thus test its value. Although many diggings are found away from the

bank of a stream, the river-sides are the places where gold is generally

first looked for and worked. In saying this, of course I [except the

gold in quartz, of which I shall have to speak hereafter. The spots

first searched are generally those upon the bank of a river where the

deposit consists of a thick, stiff mud or clay, with stones. In some

cases this is covered with sand, so that the surface has to be removed

before the “pay dust” is revealed. All these workings on river-banks are

called “bars,” and are usually named after the prospecter, or from some

incident connected with their discovery.

When the Prospecter conies to dirt which looks as if it would pay, he

unslings his pan from his hack, and proceeds to test it. This he effects

by filling his pan with the earth, then squatting on the edge of the

stream, he takes it by the rim, dipping it in the water, and giving it a

kind of rotary motion stirring and kneading the contents occasionally

until the whole is completely moistened. The larger stones are then

thrown out, the edge of the pan canted upwards, and a continual flow of

water made to pass through it until, the lighter portion of its contents

being washed away, nothing but a few pebbles and specks of black

metallic sand are left, among which the gold, if there is any, will be

found. The rotary movement, by which the heavier pebbles and bits of

gold are kept in the centre of the pan, and the lighter earth allowed to

pass over its edge, requires considerable practice, and an unskilful

prospector will perhaps pass by a place as not being worth working that

an experienced hand will recognise as very rich. The specific gravity of

the black sand being nearly equal to that of the gold, while wet they

cannot be at once separated, and the nuggets, if any, being taken out,

the pan is laid in the sun or by a fire to dry. When dry the lighter

particles of sand are blown away; or if the gold is very fine it is

amalgamated with quicksilver. The miners know by practice how much gold

in a pan will constitute a rich digging, and they usually express the

value of the earth as “ 5/’ “ 10,” or “ 15 cent dirt,” meaning that each

pan so washed will yield so much in money. Panning, it may be remarked,

never gives the full value of the dirt, as may be imagined from the

roughness of the process. If the gold should be in flakes, a good deal

is likely to be lost in the process, as it will not then sink readily to

the bottom of the pan, and is more likely to be washed away with the

sand. In panning, as well as, indeed, in all the other primitive

processes of washing gold, the superior specific gravity of this metal

over others, except platinum, is the basis of operations; all depending

Aon its settling at the bottom of whatever vessel may chance to be used.

The “pan” is hardly ever used except for prospecting, so that the

“rocker” or “cradle” may be described as the most primitive appliance

used in gold-washing. In the winter of 1859, when I first went up the

Fraser, the rocker was the general machine—the use of sluices not having

then begun. It was used in California as early as 1S4S, being-formed

rudely of logs, or the trunk of a tree. And yet, ungainly as they were,

they commanded, before saw-mills were established in the country,

enormous prices.

The rocker, then, consists of a box 34 to 4 feet long, about 2 feet

wide, and 14 deep. The top and one end of this box are open, and at the

lower end the sides slope gradually until they reach the bottom. At its

head is attached a closely-jointed box with a sheet-iron bottom, pierced

with holes sufficiently large to allow pebbles to pass through. This

machine is provided with rockers like a child’s cradle, while within

cleets are placed to arrest the gold in its passage. One of the miners

then, the cradle being placed by the water’s edge, feeds it with earth,

while another rocks and supplies it with water. The dirt to be washed is

thrown into the upper iron box, and a continual stream of water

being-poured in, it is disintegrated, the gold and pebbles passing-down

to the bottom, where the water is allowed to carry the stones away, and

the cleets arrest the precious metal.

'When the gold is very fine I have seen a piece of cloth laid along the

bottom box, covered with quicksilver to arrest the gold. When a party of

miners work with rockers, they divide the labour of rocking, carrying

water, if necessary, and digging equally among themselves. The rocker is

the only apparatus that can be at all successfully worked singlehanded;

and rough as it appears and really is, I have seen men make 30 to 50

dollars a day with it, while far greater sums have been known to be

realized by it. In these remarks I have assumed that my readers

generally are aware that quicksilver arrests whatever gold passes over

it, and, forming an amalgam with it, retains it until it is retorted

from it. In washing gold, quicksilver has to be used always, except

where the mineral is found very large and coarse. Even then the earth is

generally made to pass over some quicksilver before it escapes

altogether, in order to preserve the finer particles. I may here mention

that in a “sluice” of ordinary size 40 or 50 lbs. of quicksilver are

used daily; in a rocker perhaps 8 or 10 lbs. Of course the same

quicksilver can be used over and over again when the gold has been

retorted from it.

The first improvement on the “Rocker” was by the use of a machine called

the “Long Tom.” This, though common enough in California, I never saw

used in British Columbia. It consists of a shallow trough, from 10 to 20

feet long, and 16 inches to 2 feet wide. One end is slightly turned up,

shod with iron, and perforated like the sieve of a rocker. The trough is

placed at an incline, sieve-end downwards. A stream of water is turned

into the upper end of the Tom, and several hands supply it with earth,

which finds its way to the sieve, carrying along with it the gold, which

it washes or disintegrates in its passage. Immediately beneath the sieve

a box is placed, in which are nailed cleets, or as they are more

generally termed “Riffles,” which catch the gold as in the rocker. When

the gold is fine another box containing quicksilver is placed at the end

of the riffle, to catch the gold which passes it.

A man always attends at the end to clear away the “Tailings,” or earth

discharged from the machine, and also to stir up the earth in the Tom,

and keep the sieve clear of stones, an iron rake being used for the

purpose. By the use of the “Long Tom,” rather than the cradle, a great

saving is effected; the work being performed in a much more thorough

manner. It is estimated in California tliat the Tom will wash ten times

as much earth as a cradle, employing the same number of hands.

The next important method is “Sluicing.” This is by far the most

commonly used both in British Columbia and California, employing, I

suppose, one-half the mining population of both couutries.

Sluicing is, moreover, an operation which can be carried on on any

scale, from two or three men upon a river bar, to a rich company washing

away an entire hill by the “Hydraulic” process. Whatever may be the

scale of the operations, however, “sluicing” is necessarily connected

with a system of “ flumes,” or wooden aqueducts of greater or less

extent, either running along the back of a river-bar, and supplying the

sluices at it, or cob webbing and intersecting the whole country as in

California. I have seen flumes on the Shady Creek Canal there, conveying

an enormous stream of water across a deep ravine at the height of 100 to

200 feet.

“Sluice-boxes” are of various sizes, but generally from 2 to 3 feet

long, by about the same width. These are fitted closely together at the

ends, so as to form a continuous strongly-built trough of the required

length, from 15 or 20 to several thousand feet, their make and strength

depending entirely upon the work they have to do. I will here describe

sluicing upon a moderate scale, as I found it in practice at Hill’s Bar

upon the Fraser during my visit there in 1858.

This bar was taken up in claims early in 1858, its size being then about

1½ mile, although it has since been much extended, the richness of the

soil proving, I believe, greater as it is ascended. In this place, then,

a flume was put up, carrying the water from a stream which descended the

mountain at its southern end along the whole length of the bar, and

behind those claims which were being worked. From this flume each miner

led a sluice down towards the river; his sluice being placed at such an

angle that the water

Would run through it with sufficient force to carry the earth, but not,

of course, the gold with it. Its strength, indeed, is so regulated as to

allow time for the riffles and quicksilver to catch the gold as it

passes. The supply of water from the flume to each sluice is regulated

by a gate in the side of the flume, which is raised for so much per

inch. The price paid for water of course varies greatly with the cost of

timber, engineering difficulties of making the flume, Ac. It is

ordinarily established by the miners, who meet and agree to pay any

individual or company who may undertake the work a certain rateable

rental for the water. Their construction, indeed, is one of the most

profitable of colonial speculations. The flume I am now speaking of cost

7000 or 8000 dollars, and each miner paid a dollar an inch for water

daily. Since that time it has become much cheaper, and the usual price

is about 25 cents (Is.) an inch, the width of the gate being 1 foot. The

sluice-boxes here were very slight, about inch-plank, as the dirt which

had to pass through them was not large. In the bottom of each box was a

grating, made of strips of plank nailed crosswise to each other, but not

attached to the box like the riffles. In the interstices of these

gratings quicksilver is spread to catch the fine gold, the coarse being

canght by the grating itself. The sluice is placed on tressels or legs,

so as to raise it to the height convenient for shovelling the earth in;

the water is then let on, and several men feed the sluice with earth

from either side, while one or two with iron rakes stir it up or pull

out any large stones -which might break the gratings.

Such is the working of ordinary sluices; but sluicing is also

inseparable from the grandest of all mining operations—viz., “Hydraulic

Mining.” Hydraulic mining, as I witnessed it at Timbuctoo in California,

is certainly a marvellous operation. A hill of moderate size, 200 to 300

feet high, may often be found to contain gold throughout its formation,

but too thinly to repay cradle-washing, or even hand-sluicing, and not

lying in any veins or streaks which could be worked by tunnelling or

ground-sluicing.

A series of sluice-boxes are therefore constructed and put together, as

described above; but in this case, instead of being of light timber,

they are made of the stoutest board that can possibly be got, backed by

cross-pieces, &c., so as to be of sufficient strength to allow the

passage of any amount of earth and stones forced through them by a flood

of water. The boxes are also made shorter and wider, being generally

about 14 inches long by 3 to 4 feet wide—the bottoms, instead of the

gratings spoken of above, being lined with wooden blocks like

wood-pavement, for resisting the friction of the debris passing over it,

the interstices being filled with quicksilver to catch the fine gold.

The sluice, thus prepared, is firmly placed in a slanting position near

the foot of the hill intended to be attacked.

To shovel a mass of several million tons of earth into these sluices

would prove a tedious and profitless operation. In its stead, therefore,

hydraulic mining is called into play, by which the labour of many men is

performed by water, and the hill worn down to the base by its agency.

The operation consists of simply throwing an immense stream of water

upon the side of the hill with hose and pipe, as a fire-engine plays

upon a burning building. The water is led through guttapercha or canvas

hoses, 4 to 6 inches in diameter, and is thrown from a considerable

height above the scene of operations. It is consequently hurled with

such force as to eat into the hill-side as if it were sugar. At the spot

where I saw this working in operation to the greatest advantage they

were using four horses, which they estimated as equal to the power of a

hundred men with pick and shovel. There is more knowledge and skill

required in this work than would at first sight be supposed necessary.

The purpose of the man who directs the hose is to undermine the surface

as well as wash away the face of the hill. He therefore directs the

water at a likely spot until indications of a “cave-in” become apparent.

Notice being given, the neighbourhood is deserted. The earth far above

cracks, and down comes all the face of the precipice with the noise of

an avalanche. By this means a hill several hundred feet higher than the

water could reach may easily be washed away.

The greatest difficulty connected with hydraulic work is to get a

sufficient fall for the water—a considerable pressure being, of course,

necessary. At Timbuctoo, for instance, a large river flowed close by,

but its waters at that point were quite useless from being too low; the

consequence was, that a flume had to be led several miles, from a part

of the river higher up, so as to gain the force required. Supplying

water for this and similar mining purposes has, therefore, proved a very

successful speculation in California. I am not able to give the exact

length of the longest flumes constructed there, but I know that it has

in some cases been found necessary to bring water from the Sierra

Nevada, and to tap streams that have their rise there. It is not at all

uncommon to bring it from a distance of 50 miles, and in some cases it

has been conveyed as far again.

The expense of this is, of course, enormous, and it is in the ready

supply of water at various levels, that the work of mining in British

Columbia will be found so much more easy than in California. So scarce

is it there, indeed, that it sometimes has been found cheaper to pack

the earth on mules and carry it to the river-side than to bring the

water to the gold-fields.

The difficulty of obtaining water in the early days of gold-digging in

California gave rise to a very curious method of extracting the mineral,

which, I believe, was only practised by the Mexicans. Two men would

collect a heap of earth from some place containing grain-gold, and pound

it as fine as possible. It was then placed in a large cloth, like a

sheet, and winnowed—the breeze carrying away the dust, while the heavier

gold fell back into the cloth. Bellows were sometimes used for this

purpose also.

While upon this subject, I will take the opportunity of describing the

most common appliance for raising water from a river for the use of a

sluice on its bank. The machinery used is known as the “fiutter-wheel,”

and the traveller in a mining country will see them erected in every

conceivable manner and place. It is the same in principle and very

similar in appearance to our common “undershot-wheel,” consisting of a

large wheel 20 to 30 feet in diameter, turned by the force of the

current. The paddles are fitted with buckets made to fill themselves

with water as they pass under the wheel, which they empty as they turn

over into a trough placed convenient for the purpose and leading to the

sluice. In a river with a rapid current, like the Fraser, they can be

made to supply almost any quantity of water.

There is a kind of intermediate process between that which I have just

described and tunnelling or “koyoteing,” partaking in a measure of both.

This is called “ground-sluicing,” and is quite distinct from “sluicing.”

The reader will better understand this process if I speak of

“koyoteing,” and “ground-sluicing” together, the latter having become a

substitute for the former.

As the miners in California began to gain experience in gold-seeking,

they found that at a certain distance beneath the surface of the earth a

layer of rock existed, on which the gold, by its superior specific

gravity, had gradually settled. Experience soon taught the miner to

discard the upper earth, which was comparatively valueless, and to seek

for gold in the cracks or “pockets” of this bed-rock, or in the layer of

earth or clay covering it. The depth of this rock is very various ;

sometimes it crops out at the surface, while at other times it is found

150 to 200 feet down. Where it is very deep, recourse must be had to

regular shaft-sinking and tunnelling, as in a coal or copper mine; but

when the rock is only 20 or 30 feet beneath the surface, tunnelling on a

very small scale, known as “koyoteing,” from its fancied resemblance to

the burrowing of the small wikl-clog common to British Columbia and

California, is adopted. These little tunnels are made to save the

expense of shovelling off the 20 or 30 feet of earth that cover the “

pay dirt ” on the bedrock, and their extraordinary number gives a very

strange appearance to those parts of the country which have been

thoroughly “koyote-ed.” I have seen a hill completely honeycombed with

these burrows, carried through and through it, and interlacing in every

possible direction. So rich is their formation, however, that after they

have been deserted by the koyote-ers they are still found worth working.

I remember looking at one in the Yuba county in California which

appeared so completely riddled that the pressure of a child's foot would

have brought it down. Upon my expressing my conviction that anyhow that

seemed worked out, a miner standing by at once corrected me. “Worked

out, sir?” he said—“not a bit of it! If you come in six months, you’ll

not see any hill there at all, sir. A company are going to bring the

water to play upon it in a few days.” “Will it pay well, do you

suppose?” “All pays about here, sir,” was the quick reply; “they’ll take

a hundred dollars each a-day.”

The Koyote tunnels are only made sufficiently high for the workman to

sit upright in them. They are generally carried through somewhat

stiffish clay, and are propped and supported with wooden posts, but, as

may be imagined in the case of such small apertures extending for so

great a length as some of them do, they are very unsafe. Not

unfrequently they “cave in” without the slightest warning. Sometimes,

too, the earth settles down upon the bed-rock so slowly and silently,

that the poor victims are buried alive unknown to them companions

without.

The danger of this work and its inefficiency for extracting the gold,

much of which was lost in these dark holes, gave rise, as the agency of

water became more appreciated, to “ground-sluicing.” This consists in

directing a heavy stream of water upon the bank which is to be removed,

and, with the aid of pick and shovel, washing the natural surface away

and bringing the “pay-streak” next the bed-rock into view.

Before proceeding to the subject of quartz-crushing, it will be well

perhaps to give the reader some further idea of the great extent of

those mining operations which, begun by a few adventurers, have become a

regularly organised system, carried on by wealthy and powerful

companies. As a striking monument of their courage and the extent of

their resources, I would instance the fact of their having diverted

large rivers from their channels so as to lay their beds dry for mining

purposes. This has been done at nearly every bend or shallow in the

numerous streams of California, and will doubtless be imitated in

Columbia ere long. The largest of these operations that I ever saw was

near Auburn, a large town in Placer county, on the American river.

Sometimes the water can be brought in a strongly-built flume from above,

and carried by a long box over the old bed of the river ; at other times

a regular canal has to be made and dams constructed upon a very large

scale. The result is that the bed of the river is laid dry, when its

every crevice and pocket is carefully searched for the gold which the

water has generally brought down from the bases of the hills and the

bars higher up the stream. These operations are frequently so extensive

as to occupy several successive seasons before the whole is worked, and

to employ hundreds of labourers besides the individuals composing the

company, who usually in such an enterprise number fifty or sixty.

Sometimes the premature approach of the rainy season, and consequent

freshets, carry away the whole of the works in a night. These works

occasionally yield immense returns, and it is not unfrequently found, on

renewing them alter the rainy season, that fresh deposits of gold have

taken place, almost equal in value to the first. On the other hand, no

amount of judgment can select with any degree of certainty a favourable

spot for “jamming” or turning a river, and, after months of hard labour,

the bed when laid bare may prove entirely destitute of gold deposits.

The long space of still water below a series of rapids will sometimes be

found in one spot to contain pounds of gold, while in another the

workers who have selected that portion of the river above the rapids

will find themselves in the paying place.

All gold operations, indeed, depend very much upon chance for success.

No one can ever 'calculate with any degree of certainty on the run of

the “lode” underground, or in the “pay streak” near the surface. Thus it

is ever a lottery. As an instance of this on a large scale, I remember

when I was at Grass Valley, “Nevada county,” going to see the working at

the “ Black Bridge ” tunnel there. The first shaft for this tunnel was

sunk five years before my visit, and up to that time nothing had been

taken, though it had been constantly worked and wTas nearly 20,000 feet

long. It was commenced in 1855 by a company, who sunk a shaft nearly 250

feet, to strike, as they hoped and expected, a lode from the opposite

side of the valley. The original company consisted of five men, and in

the course of the five years some of them gave up and others joined,

part of them working at other diggings to get money for provisions,

tools, &c., to keep their firm going. At length, just before my visit,

all the original projectors, and about three sets of others who had

joined at different periods, gave the enterprise up as hopeless after

carrying it, as I have said, nearly four miles. A new company then took

possession of it and summoned the miners of the valley to a

consultation. The meeting decided that they had not gone deep enough,

and the shaft was accordingly sunk 50 feet lower, when the gold was at

once struck. I tried to ascertain what had been expended upon this

tunnel, but it had passed through so many hands that it was impossible

even to estimate it. The gentleman who showed me over it, and who was an

Englishman and the principal man of Grass Valley (Mr. Attwood), said it

would cost the new company 12,000 or 14,000 dollars (3000Z.) before they

took out anything that would repay them. The recklessness with which

money is risked and the apparent unconcern with which a man loses a

large fortune, and the millionaire of to-day becomes a hired labourer

to-morrow, is one of the most striking characteristics of the American

in these Western states. It is owing in a great degree to the mere

accident which gold-working is. The effect of this upon society is of

course most injurious. The poor miner, hobbling along the street of San

Francisco or Sacramento trying to borrow—for there are no beggars in

California—money enough to take him back to the mines from which ague or

rheumatism have driven him a few months before, knows that a lucky hit

may enable him in a very short time to take the place of the gentleman

who passes by him in his carriage, and whose capital is very probably

floating about in schemes, the failure of which will as rapidly reduce

him to the streets, or send him back again to the mines as a labourer.

The spirit, too, which these changes of fortune are borne is wonderful.

I travelled once in California with a man who was on his way to the

mines to commence work as a labourer for the third time. He told me his

story readily: it was simple enough. He had twice made what he thought

would enrich him for life, and twice it had gone in unlucky

speculations. An Englishman under these circumstances would probably

have been greatly depressed: not so my fellow-traveller. He talked away

through the journey cheerfully, describing the country as Ave passed

through it, speaking of the past without anything like regret, and

calmly hopeful for the future.

To return to the gold-working, however. I have described the various

processes of extracting it from the earth or the rock-surface. I come

now lastly to the more arduous work of collecting it from the rock

itself, known as quartz-crushing. Some very rich specimens of quartz

have been found in British Columbia, near Lowkee Creek, Cariboo, and in

other places. But while the surface-diggings continue to yield such rich

returns and transport is so dear, it can scarcely be expected that

quartz-crushing, which requires the use of ponderous machinery, will be

commenced. The richest quartz district in California is Grass Valley, in

Nevada county, which place, as I have before observed, I visited in

1860. In this valley there are forty steam-mills at work, drawing the

earth from tunnels, crushing quartz, &c. The average value of the quartz

there is 60 or 70 dollars a ton, though it sometimes runs as high as 200

dollars per ton. The Helvetia mill, which is one of the best, crushes on

an average 30 tons daily, making therefore nearly 2000 dollars (1007).

The quartz is picked or blasted out in the usual way, and then conveyed

on mules or by tramway to the mill, where it is broken by hand into

pieces about the size of an egg.

The machinery is placed under a large shed or wooden building of some

kind. It consists of a series of heavy stampers, made of iron, or wood

shod with iron, the lower ends of which fit into boxes in which the

quartz is placed. The stampers are moved by cogs connected with a

revolving wheel, which lifts them and lets them fall into the boxes. The

Helvetia mill works thirty-four of these stampers. The stamping-boxes

are supplied with water by a hose or pipe on one side, while at the

other side is a hole through wdrich the quartz, as it is crushed, passes

out in the form of a thick white fluid. As it comes out it is received

upon a framework, placed at such an angle that it passes slowly over it:

on this frame are several quicksilver riffles, which catch and

amalgamate the gold as it glides along. Beyond this again is another

frame, over which is spread a blanket, which arrests any fine particles

which escape the quicksilver. Even with all this care there is

considerable waste, and the “tailings” or refuse is generally worth a

second washing. No way has yet been found of obviating this waste.

There is a more primitive method of quartz-crushing called the “rastra,”

or drag, which, though it will only crush about a ton a day, does its

work more perfectly than the stampers. For this purpose a circular

trough is made, and paved at the bottom. In the centre of this an

upright post is fixed, with a spindle fitted into a frame at the top, so

that it can be turned round. Through the lower part of this a horizontal

pole is passed, one end of which plumbs the edge of the trough, while

the other projects some way beyond it. To the short end a couple of

heavy stones are attached; a mule or horse being harnessed to the other.

The quartz is then put into the trough, being first broken up small, and

ground by the friction of the stones, which are dragged round by the

mule. A small stream of water is kept constantly flowing into the

trough, and quicksilver is sprinkled in at intervals to amalgamate with

the gold. After a certain time the water is turned off, the entire

pavement of the trough taken up, and the amalgam carefully collected and

retorted. Of course these are worked chiefly by parties who do not

possess sufficient capital to construct steam-mills.

With respect to the existence of the precious mineral in North America,

the theory which Sir Roderiek Murchison maintains is that the matrix

will be found extending the whole way along the slopes of the chain of

mountains lying between the Rocky Mountains and the Coast Ridge. This

theory is borne out by the discoveries in Rock Creek and Cariboo, which

lie in the line attributed to it. All the river bars or “placers,” as

surface-diggings are called, which have been worked as yet are

undeniably the alluvial deposits brought down by the streams on whose

banks they are found. And nearly all these rivers take their rise in the

chain of mountains spoken of, which form an almost unbroken line between

Bock Creek and Cariboo. The Cariboo Lake and some of the rich Cariboo

diggings, as Iveithley’s Creek, Cottonwood River, &c., are on the west

side of this ridge; while Antler Creek, Canon Creek, and others lie on

the east, showing that the gold is common to both slopes. This has

probably tended to make the Fraser River bars much richer than they

otherwise would have been, as all the small streams which rise on the

eastern side of these mountains also run into the Fraser, which comes up

from the southward behind them, till, as I have before shown, it is

turned southward by the height of the land between it and the Peace

River.

The few adventurers who have crossed this barrier to the Peace River

report all the appearances of an extremely rich auriferous region there;

and Mr. Kind tells me that it is generally believed at Cariboo that the

richest diggings will be found in that direction. This fact undoubtedly

confirms Sir E. Murchison’s theory, as the Peace River Valley stretches

northward in the same direction till it meets the Finlay River in lat.

56 N.

It would be simply waste of space to quote the accounts of the richness

of the gold-fields of British Columbia, given at intervals in the

journals of the day. New and more startling discoveries are being so

constantly made, that the marvels of one day are always likely to be

eclipsed by the still more extraordinary reports of the next. We have

also yet to receive the accounts of this summer’s work at the

gold-fields. I will give, however, from the Times of February 6, 1862,

the estimate which its correspondent forms of the approximate gross

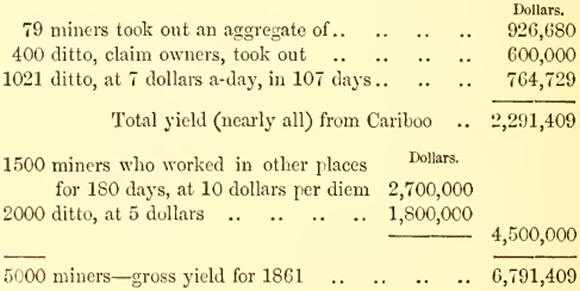

yield of gold for 1861:—

“It is impossible to give a return of the ‘yield ’ of gold produced by

British Columbia in the aggregate with certainty. I shall merely attempt

an approximation of the gross yield from the best data within my reach.

“It is generally conceded that, including Chinese, there were 5000 men

engaged in gold-digging this year. The various Government returns of

Customs duties and of interior tolls of roads charged on the passage of

merchandise collected, justify this assumption, while the miners’

licences issued tend to corroborate it. The mining population in the

Cariboo country, including within this division the Forks of Quesnelle

River (50 miles below) is put down on general testimony (of miners,

travellers, other residents, and Government returns) at 1500 men. To

work out the earnings of this aggregate of 5000 miners, I adopt a

statement of names and amounts, made up from miners’ information, of 79

men who together took out in. Cariboo 926,680 dollars. The general

opinion of the miners is, that (in addition to the ‘lucky ones’ who made

‘big strikes,’ and which I limit to the above number of 7 9) every man

who had a claim or a share in a claim made from 1000 to 2000 dollars. Of

these there were at the least 400, and taking their earnings at a medium

or average between the two sums mentioned—say at 1500 dollars to

each—they would produce 600,000 dollars. There remain 1021 men to be

accounted for. Putting their earnings at 7 dollars a day each, which is

the lowest rate of wages paid for hired labour in the Cariboo mines, and

assigning only 107 working days as the period of their mining operations

during the season, to make allowance for its shortness by reason of the

distance from the different points of departure and of bad weather, they

would have taken out 764,729 dollars. These several sums added would

make the yield of Cariboo and Quesnelle 2,291,409 dollars to 1500 men

for the season, by far the greater portion, or nearly all, in fact,

being from Cariboo; although the north fork of Quesnelle is also very

productive and so rich as to induce its being worked by fluming this

winter by about 100 miners, who have remained for the purpose.

“The remaining 3500 of the mining population who worked on Thompson’s

River, the Fraser, from Fort George downwards; Bridge River, Semilkameen,

and Okanagan (very few), Rock Creek, and all other localities throughout

the country, I shall divide into two classes: the first to consist of

1500, who made 10 dollars a-day for—say 180 days (Sundays thrown off),

and which would give 2,700,000 dollars for their joint earnings; the

second and last class of 2000 men, who were not so lucky, I shall assume

to have made only 5 dollars each a-day for the same period, and which

would give 1,800,000 dollars as the fruit of their united labour.

“The three last categories, which number 4521 men, include the many

miners who in Cariboo were making 20 to 50 dollars a-day each, as well

as those who, in various other localities, were making from 15 dollars

to 100 dollars a-day occasionally, so I think my estimate, although not

accurate, is reasonable and moderate. The Government people think I have

rather understated the earnings of the miners in these three classes of

4521 men ; and the Governor himself, who takes an absorbing interest in

the affairs of this portion of his government, and to whose ready

courtesy I am indebted for some of the information given in this letter,

as well as for much formerly communicated in my correspondence, thinks

my estimate is a very safe one.

“But I must finish this long letter with a recapitulation, for I dread

the inroads I have made upon your space:—

“This does not include

the native Indians, as I have no means of estimating their earnings.

They are beginning to ‘dig,’ in imitation of the white men, in some

parts, and will eventually increase the yield of gold, as the desire for

wealth grows upon them. As a proof of their aptitude and success in

this, to them, new field of labour, I may mention that the Bishop of

Columbia found a gang of them 'washing’ on Bridge River last summer, and

that he had the day’s earnings of one Indian weighed when he ceased his

labours, and found it to contain one ounce of gold. His Lordship

purchased it of him, paying him 16 dollars 50 cents, the current issue,

and carried it away as a souvenir.”

The return of the assays of Cariboo gold, given by the same gentleman,

are also of permanent interest, as showing the value of the dust. The

highest assayed by Messrs. Marchand and Co., from whom the return is

obtained, from Davis Creek, was 718 fine, value per ounce 18 doll. 97.64

c., or about 31.19s. The lowest, which came from Williams Creek, was 810

fine, value per ounce 16 doll. 74.42 c. (about 31. 9s. Id.). The average

value of all Cariboo dust is 854 fine, value per ounce 17 doll. 65.37 c.

(3/. 13s. 6d.).

In conclusion, I have merely to add, that I remained with the 'Hecate’

at San Francisco until she was repaired, when, on the 21st October,

1861, I left that place in the United States mail steamer 'Orizaba,’ and

on the 27th November arrived “home.” |