|

THE LITERATURE OF

EASTERN AND CENTRAL CANADA.

THE heroic age in

Canada is not lacking in subjects worthy of the pen of the historian,

novelist or poet, or the pencil and brush of the artist. Some of our

most noted American writers explored the untrodden field of native lore

for original subjects, and their laurels were won in revealing the

heroism of savages, the gracefulness and beauty of swarthy maidens, the

stirring deeds of a period supposed by many to be a barren waste, and

the strength and purity of intellect and Imagination, and the deep

religious spirit of the red men hidden in their mythology and customs.

Albert Gallatin laid the foundation of our study upon this continent of

the Indian languages, the results of his studies being embodied in his

great work, "Synopsis of the Indian Tribes of North America." He was

followed by two scholars eminent in the field of native lore —Peter S.

Duponceau and the Moravian missionary, John Heckewelder. The most

industrious of all investigators in the study of the customs, traditions

and languages of the red men was Henry B. Schoolcraft, who devoted more

than thirty years to the amassing of information and the publication of

works relating to the languages and folk-lore of the natives of the

northern part of the continent. He published "Oneota," "Algic

Researches," which was afterwards issued as "The Myth of Hiawatha,"

"Notes on the Iroquois, "Personal Memoirs of a Residence of Thirty Years

with the Indian Tribes," and his greatest work "History, Condition and

Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States." This last work was

published by the American Government in six quarto volumes, and has been

characterized by Parkman as "a, singularly crude and illiterate

production, stuffed with blunders and contradictions, giving evidence on

every page of a striking unfitness either for historical or scientific

inquiry, and taxing to the utmost the patience of those who would

extract what is valuable in it from its oceans of pedantic verbiage."

The chief merit of Schoolcraft's works has been the preservation of

valuable documents. He was lacking in critical power, unable to select

wisely, but was intensely in earnest in collecting facts and fancies,

which he oftentimes erroneously interpreted.

Longfellow's poem on

Hiawatha was based on the myth which Schoolcraft had dug from the

folk-lore of the Ojibways, and the success of the poem directed the

reading public to the intensely interesting character of the legendary

lore of the natives of the New Continent. Fenimore Cooper followed in

the train of these investigators, weaving facts and fancies into

stirring works of fiction, which found a numerous host of readers in the

Old and New Worlds, and seem to be as popular as when written. The

interest awakened by Heckewelder and Cooper in the red men aroused other

writers to employ their pens in this special field of romance, and among

the numerous novels produced were Simm's stirring story, "The Yemassee,"

and the pathetic tale, "Ramona," by Helen Hunt Jackson, aptly named the

Uncle Tom's Cabin of the American Indian race.

The heroic age in

Canada is not a barren period, but abounds in subjects for the writer of

prose and the maker of poetry. The French period is prolific in

materials relating to the life of the forest rangers and voyageurs. The

adventures of Du Lhut, the Robin Hood of the Canadian greenwood, after

whom the City of Duluth is named, would make a stirring volume for the

youth of our land. Longfellow found on Canadian soil the subject for his

immortal poem "Evangeline"; and Parkman, delving deep in our archives,

resuscitated the hidden lore of other days, and won immortal fame. Much

remains to be written of the virtues of Madame Perade, who is known as

the youthful heroine of Vercheres, when, as a girl of fourteen, she

faced a band of Iroquois warriors and saved a fort by her courage and

wonderful presence of mind. The pen of the ready writer can find an

appropriate subject in the legend of the death of Father La Brosse, the

devoted missionary among the Mon-tagnais, in the Saguenay region. He

died at Tadousac, and the old folks say 011 that night the bells in all

the mission churches which he served, on the mainland and on the islands

of the Lower St. Lawrence, tolled of their own accord, all the people

crying, " Alas! our good missionary is dead; he warned us we should

never see him more."

Charlevoix, the famous

French traveller and early historian of Canada, in his " Histoire de la

Nouvelle France," published in 1744, and " Letters to the Duchess of

Lesdiguieres," gave much valuable information relating to Canada and the

Canadian Indians. Besides treating of the French posts and settlements,

the mines, fisheries, plants and animals, the lakes, waterfalls and

rivers, and the manner of navigating them, he treated of the character

of the native tribes, their customs and traditions, languages,

government and religion. The languages of Canada upon which he made

special comments, were the Huron, Algonquin and Pottawatomi. His history

was praised by scholars and freely ([noted as an authority, yet it was

not until 1865 that an English edition was published, which was issued

in six volumes at New York, by John Gilmary Shea.

Father Gabriel $agard

was one of our earliest Huron scholars. In 16:32 there was published in

Paris " Le Grand Voyage rlu pays des Hurons," which was followed by a

dictionary of the Huron language, and in 1636 his "Histoire du Canada et

Voyages que les freres Mineurs Ilecollets y out faiets pour la

Conversion des Infid&les depuis l'an 1615." We are indebted to Father

Sagard for many facts relating to the customs of the Hurons, their

religious belief and political system. Another of the early historians

was Marc Lescarbot, who, in 1609, published his "History of New France"

in the French language. The historians of the French period were not men

of the study, who formed their opinions by consulting manuscripts and

books, but they were priests who travelled extensively among the native

tribes, learning the languages and becoming conversant with the savage

customs and belief of their dusky adherents, as they taught them the way

of the cross ; or they were soldiers and adventurers, who became

enamoured of the forest life, or were aroused by a spirit of enterprise

and desire for discovery; and as they travelled gathered information and

formed their opinions through personal observation. Scattered throughout

the pages of their books are discussions on the languages of the

natives, with short vocabularies, folk-tales, traditions and recitals of

religious feasts.

Lescarbot's writings

were no exception, and in his pages are to be found a discussion on the

languages of the natives, with short vocabularies of the Algonquin,

Huron, Etchemin and Souriquois. Baron de la Hontan's "Nouveaus Voyages"

were published in Paris and London in 1703. La Hontan arrived in Canada

in 1683, and was stationed as a soldier at several important forts,

including Frontenac, Niagara and St. Joseph. His military duties gave

him opportunities of seeing the country and learning something of the

natives; but truth and fiction are so blended in his writings that they

have long since ceased to have any authority. The intrepid explorer and

historian, Samuel de Champlain, was in the habit of keeping a journal of

his observations, which was published in several volumes. In 1603, a

small book of eighty pages was issued, entitled "Des Sauvages," giving

an account of his voyage across the Atlantic and a description of the

Gulf and River St. Lawrence, with numerous details of the scenery, the

animals and birds, and the character and habits of the natives. "Les

Voyages du Sieur de Champlain" was published in 1613, "Voyages et

Descouv-ertures" in 1619, and "Les Voyages de la Nouvelle France

Occidentale" in 1632. The genial Governor of New France relates, with

the skill and confidence of a close observer of the ways of nature and

men, his dealings with the savages, the dress, war and burial customs,

feasts and religious ideas of the natives, the missions of the Recollet

Fathers, his explorations on the Ottawa, Lakes Nipissing, Huron and

Ontario, with reflections upon the Huron and neighboring Indian tribes.

Chaniplain's volumes are a mine of lore relating to early Canadian

history and the native tribes of Canada inhabiting the provinces of

Ontario and Quebec. Boucher, the Governor of Three Rivers, published at

Paris, in 1664, a faithful but superficial account of Canada, detailing

the habits of the savages and the condition of the country. In the same

year the Pere du Creux issued his tedious Latin compilation of the

Jesuit Relations, with some additions from another source, bearing the

title "Historian Canadensis." A rare historical account of the French

colony and the missionary work of the Recollet Fathers was given by Le

Clercq in 1691, and published in two volumes, with the title "Etablissement

de la Foi," as also another work, "Nouvelle Relation de la Gaspdsie," in

the same year. Tire Jesuit Lafitau published at Paris, in 1724, his "Moeurs

des Sauvages Ameriquains," in two volumes, with various plates. The

author had spent several years among the Iroquois, and his work deals

chiefly with the Indians It is of great historical value, as Lafitau was

a careful observer, and narrated accurately the results of his travels.

Parkman says he is "the most satisfactory of the elder writers;" and

Charlevoix said, twentj' years after the book was published, "We have

nothing so exact on the subject." Bacqueville de la Potherie published,

in 1722 and again in 1753, his "Histoire de rAmerique Septei. rionale,"

in four volumes. Although characterized by Charlevoix as an undigested

and ill-written narrative, it has been frequently quoted, and is a

respectable authority upon the French establishments at Quebec, Montreal

and Three Rivers ; but its chief value lies in the faithful account of

the condition of the Indians from 1534 to 1701. In 1791 there was

published in London "Voyages and Travels of an Indian Interpreter and

Trader," by John Long. This work gives an account of the posts on the

St. Lawrence and Lake Ontario, the fur trade, and the observations of

the writer during his residence in the country. It contains speeches in

the Ojibway language, with English translations, numerals from one to

one thousand in the Iroquois, Algonquin and Ojibway languages and

vocabularies of the Mohegan, Shawnee, Algonquin and Ojibway.

Among English writers

on Canada and the red men in general, not including historians, poets,

or essayists, who cannot be classed as producers of Canadian-Indian

literature, are: Heriot, the Deputy Postmaster-General of British North

America, Colonel de Peyster, Judge Haliburton, and Mrs. Jameson. George

Heriot's "Travels Through the Canadas" sheds some light on the native

languages, discussing the origin of language, diversity of tongues in

America, grammatical notes and vocabulary of the Algonquin language,

with "O! Salutaris Hostia," in the Abnaki, Algonquin, Huron, and

Illinois languages. The miscellanies of Colonel de Peyster were

privately printed in 1813, at Dumfries, Scotland, and reprinted with

additions at New York in 1888. Besides the original letters of De

Peyster, Sir John Johnson and Colonel Guy Johnson, the work contains

numerous references to the Indians, a short vocabulary of the Ottawa and

Ojibway languages, and the distribution of the native tribes. The famous

author of "Sam Slick," in "A General Description of Nova Scotia," gives

some specimens of the Micmac language, including vocabulary, pronouns,

and present and imperfect tenses of the verb to dance, with English

translations. This work was printed at Halifax in 1823. Mrs. Jameson's

"Winter Studies and Summer Rambles in Canada," discusses briefly the

Ojibway language, with a few examples.

Books of travel cannot

be expected to contain more than if passing reference to the Canadian

Aborigines, and it is only when we turn to the works dealing with the

scientific aspect of the question, that we find a full discussion of the

various phases of life and thought among the natives. Fortunately we

have some writers who have studied definitely, and with enthusiasm, the

history, condition, languages, folk-lore, religion and government of the

savage folk, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and from the

international boundary line to the Arctic Ocean. Although not emanating

from Canada, yet because it treats of one of our greatest native

confederacies, the famous work "The League of the Illinois," by the Hon.

Lewis H. Morgan, must lie included in our sketch of the literature. This

is a profound study of the organization polity, customs and character of

an Indian people. Mr. Morgan was adopted a member of the Senecas, and

for nearly forty years he investigated the ancient laws and customs of

the Iroquois, producing several notable works which awakened a deeper

interest in the Indian race.

Horatio Hale, of

Clinton, Ontario, is our greatest writer on the native races. An

American by birth, upon graduating at Harvard in 1837 he was appointed

philologist to the United States Exploring Expedition under Captain

Charles Wilkes. In this capacity he studied a large number of languages

in North and South America, Australia and the Pacific Islands, and

investigated the history, traditions and customs of the people speaking

these languages. Five years were spent in preparing his special report

of the Expedition, which was published at Philadelphia in 1846, with the

title, the " Ethnography and Philology of the United States Exploring

Expedition." A large number of memoirs on anthropology and ethnology

have been read before learned societies and published. He is a member of

many scientific societies in America and Europe, and is better known

through his writings abroad than at home. His "Iroquois Book of Rites"

is a notable work, dealing with the language, history, customs and

traditions of the Iroquois. The book is a native manuscript of a

religious character, as may be seen from its name, translated by Mr.

Hale, with explanatory notes. The following memoirs are only a few of

his numerous publications: "Indian Migrations as Evidenced by Language;"

"Report on the Blackfoot Tribes," prepared under the direction of tin1

British Association;" The Development of Language;" "Race and Language;"

"Tutelo Tribe and Language;" "The Fall of HocheJaga;" "Origin of

Languages and Antiquity of Speaking Man:" "Aryans in Science and

History;" " Language as a Political Force;" " Huron Folk-Lore." Mr.

Hale's opinions as an ethnologist have been quoted extensively by

European and American students of anthropology. Sir Daniel Wilson

published several important papers on the Canadian Indians. His notable

work, "Prehistoric Man: Researches into the Origin of Civilization in

the Old and New World," included investigations in modern savagery,

based upon his earlier studies on the natives of our Dominion. His

memoirs were read before the Canadian Institute, Royal Society of

Canada, the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland and

other learned societies. Some of them were afterwards issued separately

and finally incorporated in a posthumous volume, entitled, "The Lost

Atlantis and other Ethnographic Studies." Relating especially to the

native tribes are the essays: "The Trade and Commerce of the Stone Age,"

"Pre-Aryan American Man," "The Esthetic Faculty in Aboriginal Races,"

and "The Huron Iroquois of Canada, a Typical Race of American

Aborigines."

John Reade, our notable

litterateur, wrote a few articles for The Week on "Nation Building,"

treating learnedly of the origin, tribal divisions, distribution and

gradual disappearance of the natives of our Dominion. Papers, entitled

"Some Wabanaki Songs" and "The Basques in North America," were read by

him before the Royal Society of Canada, and published in Volumes V. and

VI. of the "Proceedings and Transactions of the Society."

A. F. Chamberlain has

devoted several years of intense study to the folk-lore and languages of

our native tribes. Several of his papers have been read before the

Canadian Institute and other societies, or published as magazine

articles, and subsequently issued separately. The titles of some of his

articles are as follows: "The Relationship of the American Languages,"

"Notes on the History, Customs, and Beliefs of the Mississauga Indians,"

"Tales of the Mississaugas," "The Archaeology of Scugog Island," "The

Eskimo R|ce and Language," "The Language of the Mississaugas," "The

Kootenay Indians," "Contributions towards a Bibliography of the

Archaeology of the Dominion of Canada and Newfoundland," "Algonquin Ono-matology,

with some Comparisons with Basque," "The Thunder-Bird Amongst the

Algonquins," "Notes on Indian Child Language," "The Aryan Element in

Indian Dialects."

Dr. Silas T. Rand,

missionary among the Micmac Indians, besides numerous translations of

hymns, tracts, prayers and portions of Scripture, in the Micmac

language, wrote: "A Short Statement of Facts, Relating to the History,

Manners, Customs, Language and Literature of the Micmac Tribe of

Indians," " First Reading Book in Micmac," in the Pitman phonetic

characters, and in Roman letters; "The History of Poor Sarah, a Pious

Indian Woman," in the Micmac language; and "A Short Account of the

Lord's Work among the Micmac Indians." Dr. Rand was an assiduous

translator, well known as an industrious student of native lore, yet

excelled as a Latin and Greek scholar, the Latin versions of some of the

great hymns of the Christian Church published by him showing wide

culture and poetic genius.

Amongst the class of

writers on our Indians who may be termed scientific are the accomplished

Abbe Cuoq, missionary to the Iroquois at the Lake of Two Mountains,

author of "Jugement errone de M. Ernest Renan sur les Langues Sauvages,"

"Etudes Philologiques," and numerous translations in the Mohawk and

Nipissing tongues; David Boyle, the indefatigable investigator of native

lore, whose work as an archa3ologist in connection with his duties as

curator of the museum of the Canadian Institute is destined to bring him

prominently before the Canadian public as an enduring memorial of the

heroic days of our country; Sir J. W. Dawson, and his son, Dr. G. M.

Dawson, and Professor Campbell, of Montreal. Leaving the Indian

literature of the western part of the Dominion to be dealt with later

on, we come to the modern period of historical writings relating to the

native tribes.

A reprint of John de

Laet's "L'Histoire du Nouveau Monde," first published in Dutch in 1630

and 1633, and in French in 1640, was issued |it Quebec in 1882.

Cadwallader Colden's

History of the Five Indian Nations of Canada "was published at New York

in 1727, and in London in 1747. The native religion, customs, laws and

forms of government; the wars and treaties; the condition of the trade

of the Five Nations with the British, and their relation to the French,

with an account of some of the neighboring tribes, are treated in this

work.

Benjamin Slight

published at Montreal, in 1844, "Indian researches, or Facts Concerning

the North-American Indians."

George Copway, an

Ojibway Indian chief, born at the mouth of the river Trent in 1818, and

known by the native name, Kagegagahbowh, left Canada when a youth, and

was educated in the State of Illinois. For some years he was connected

with the press of New York, and lectured extensively in Europe and the

United States. After spending twelve years as a missionary to the

Ojibway Indians, he published, in 1847, his "Life, History and Travels,"

which passed through several editions, .and, in 1850, "The Traditional

History and Characteristic Sketches of the Ojibway Nation." The last

years of his life were spent as a missionary among his own people. He

died at Pontiac, Michigan, about 1863.

Peter Jones, the famous

missionary to the Ojibways of Canada, published at Toronto, in 1860, the

"Life and Journals of Kahkewaquonaby (Rev. Peter Jones)," and in 1861,

at London, England, his "History of the Ojibway Indians, with Especial

Reference to their Conversion to Christianity."

These works contain an

interesting account of the travels of the missionary among the Ojibways

and neighboring tribes, the traditions, native religion, and customs of

the people, with the success of missionary work among them.

Peter Dooyentate Clarke

published at Toronto, in 1870, "Origin and Traditional History of the

Wyandots, and Sketches of Other Indian Tribes of North America."

Traditional stories of Tecumseh and his League, in the years 1811 and

1812, are given, besides an historical sketch of the Huron Indians.

The Rev. George

Patterson, D.D., has written several interesting papers upon the Indians

of the eastern part of the Dominion, which have been read before learned

societies. Among his numerous papers, three notable ones have attracted

considerable attention, namely, "The Stone Age in Nova Scotia, as

illustrated by a collection of relics presented to Dalhousie College,"

"The Beothics or Red Indians of Newfoundland," and "Beothic

Vocabularies."

A. F. Hunter, of

Barrie, has devoted several years investigating the sites of the Huron

villages and ossuaries in the counties of Siincoe, York, and Ontario.

His papers on "National Characteristics and Migrations of the Hurons,"

and "French Relics from Village Sites of the Hurons," reveal the

qualifications of the successful Indian scholar, original research,

literary culture, intense enthusiasm, plodding industry, and the power

of discrimination.

Mrs. Matilda Edgar, in

1890, published at Toronto a book of great interest to Canadian readers.

"Ten Years of Upper Canada in Peace and War, 1805-1815, being the Ridout

Letters, with Annotations," besides dealing with the history of the

period, contains the narrative of the captivity among the Shawnee

Indians, in 1788, of Thomas Ridout, afterwards Surveyor-General of Upper

Canada, and a vocabulary of the Shawnee language. Mrs. Edgar is the

granddaughter of Thomas Ridout, the author of the narrative and

vocabulary. Her grandfather was captured by the Shawnee Indians, and

spent among them the spring and summer of 1788. As an instance of the

difficulties under which the captive labored in the preparation of his

diary and vocabulary, he says: "I had by this time acquired a tolerable

knowledge of their language, and began to understand them, as well as to

make myself intelligible. My mistress loved her dish of tea, and with

the tea paper I made a book, stitched with the bark of a tree, and with

yellow ink of hickory ashes, mixed with a little water, and a pen made

with a turkey quill, I wrote down the Indian name of visible objects. In

this manner I wrote two little books, which I carried in a pocket torn

from my breeches, and worn around my waist, tied by a piece of elm

bark."

Mr. Ridout died at

Toronto, February 8,1829, in the seventy-fifth year of his age.

Another valuable work

relating to the natives of our country, is "Ancient Lachine and the

Massacre of the 5th of August, 1689." The author, D. Girouard, Q.C., M.P.,

is a distinguished member of the Montreal bar and parliamentarian. Early

recitals of the old regime a beautiful description of the island of

Montreal, personal notes on De la Salle, the founder of Lachine, the

forts, Indian wars, and the trials of the early settlers are recounted

in graphic style. Charts and photographs of the early military and

religious habitations enliven the pages. At the time of the disaster of

1G89 the population of Lachine comprised three hundred and twenty souls,

not including the soldiers who kept garrison at the upper end of the

village. The Iroquois were greatly embittered against the French on

account of the treachery of the Marquis of Lenonville, Governor of New

France, who had invited a large number of unsuspecting Indians to attend

a feast at Fort Frontenac, in Cataraqui. Ninety-five accepted the

Governor's invitation, and upon their arrival they were seized, put in

irons and sent prisoners to Quebec. A few of them, including the famous

Orcanone, chief of the Five Nations, were transported to France. No

sooner had the Marquis of Lenonville left the country, and before

Frontenac had reached Canada, the Indians sought a terrible revenge;

falling suddenly upon Lachine, the village was reduced to ashes and many

of its inhabitants were killed and scalped.

The Abbd H. R. Casgrain

has been a most industrious student of Canadian history, and his works

are of great interest. His best known works, having special reference to

the Indians in their relations to the missionaries, the settlers and the

soldiers, are "Le gendes Canadiennes," 1861; "Histoire de la Mere de

1'Incarnation," 1864; "Guerre du Canada, 1756-1760, Montcalm et Levis,"

1891 ; and "Les Acadieus apres leur Dispersion."

The novelist has not

been wanting in our native literature. We have not been favored with a

Canadian Fenimore Cooper to reveal, with cultured pen, the pathos of

native life, and record the thrilling scenes of the warpath and camp.

Foreign writers have sought and found subjects for their romances among

our forests and lakes.

Numerous tales have

been written about our forest life and the red men, and the struggles of

New France. G. A. Henty's " With Wolfe in Canada " and Susanna Moodie's

"Roughing it in the Bush" and "Life in the Clearings" reveal the wealth

of story in war and peace within the borders of our fair Dominion. The

Abbe Casgrain found, in his private secretary, Joseph Marinette,

evidences of literary ability, and encouraged him to continue his

efforts, which have been eminently successful. The Abba's secretary was

born at St. Thomas de Montmorency in 1844, and in his youth became

enamoured of the novels of Cooper and Scott, which aroused his

imagination, and no doubt directed his thoughts toward the romantic

scenes of our own history. Destined for the bar, he found a more

congenial occupation in his leisure moments by writing historical

novels. He began his literary career with a few unhealthy narratives,

utterly devoid of thought and equally lacking in style." His "Charles

and Eva," a tale of the taking of Schenectady,, was unfortunate, but his

failure stimulated him to form the plan "of popularizing, by means of

dramatic presentations, the noble and glorious deeds which every

Canadian must know." Four historical novels have firmly established his

reputation—"Francois de Bieuville," 1870; "LTntendant Bigot," 1872; " Le

Chevalier de Mornac," 1873, and ' La Fiancee du Rebelle," 1875.

Mercer Adams "Algonquin

Maiden," Agnes Machar's "Stories of New France," the writings of

Macdonald, Oxley, Kingston,, and Mrs. Traill are intensely interesting,

the habits, customs, traditions and beliefs of the red men adding zest

to the historic scenes and general plots of the novels. Mary Hartwell

Cather-wood, although not a resident of Canada, has written several

admirable romances of the old days of New France and Acadie. "The

Romance of Dollard," 1889; "The Story of Tonty," 1890; and "The Lady of

Fort St. John," 1891. Francis Parkman has told, in beautiful diction,

the story of the long struggle between France and England for dominance

in North America. Canada has been laid under deep obligations to Parkman

for his laborious research and intense devotion to his task of

unravelling the knotted thread of our history. Stories of the Indian

tribes, their traditions and beliefs, their war-feasts and religious

festivals, their form of government and burial customs, their languages

and distributions, tales of the valor and intrigue of their chiefs,

speeches and style of oratory, their wars with neighboring tribes and

with their white enemies, the noble deeds of the Jesuit missionaries,

the prowess of the forest rangers and fur traders, and the adventures of

missionaries and laymen on the path of exploration enliven the pages of

this famous writer on the native tribes of Canada. The volumes dealing

especially and incidentally with the red men are: "Pioneers of France in

the New World," "The Jesuits in North America," "La Salle and the

Discovery of the Great West," "The Old Regime in Canada Under Louis

XIV.," "Count Frontenac and New France Under Louis XIV.," and "Montcalm

and Wolfe."

Major G. D. Warburton's

"The Conquest of Canada," 1849, abounds in stories of Indian life

fascinating and real, which arouse the interest of the reader and

maintain it to the end. Major John Richardson's "Wacousta," Sir George

Head's "Forest Scenes and Incidents in the Wilds of North America," and

Sellar's "Gleaner Tales" are full. of stirring incidents of adventure

among the red and white races of our own country.

Although of a religious

character, the "Jesuit Relations" are the chief source of information

from 1627 to 1672 on geographical discovery, the flora and fauna of the

country, and the languages, customs, wars, and location of the Indian

tribes. The "Relations" were issued in Paris in a series of forty-one

volumes, concerning which Charlevoix said "There is no other source to

which we can apply for instruction as to the progress of religion among

the savages, or for a knowledge of these people, all of whose languages

the Jesuits spoke. The style of these " Relations" is extremely simple;

but this simplicity itself has not contributed less to give them a great

celebrity than the curious and edifying matter they contain." Parkman's

work on "The Jesuits in North America" gives him the right to speak

authoritatively upon the "Relations," of which he says, "Though the

productions of men of scholastic training, they are simple and often

crude in style, as might be expected of narratives hastily written in

Indian lodges or rude mission-houses in the forest, amid annoyances and

interruptions of all kinds. In respect to the value of their contents,

they are exceedingly unequal. . . .

The closest examination

has left me no doubt that these missionaries wrote in perfect good

faith, and that the "Relations" hold a high place as authentic and

trustworthy historical documents. They are very scarce, and no complete

collection of them exists in America.

Passaniaquoddy and

Penobscot tribes have been thoroughly treated in an instructive and

entertaining volume by Charles G. Leland, with the title, "The Algonquin

Legends of New England." The author spent the summer of 1882 among the

Passaniaquoddy Indians at Campobello, New Brunswick, and subsequently

through interviewing members of the Micmac and Penobscot tribes, and the

assistance of persons conversant with the Indian traditions, he gathered

the materials for his interesting work, which was published at London,

1884. The Rev. W. R. Harris, Dean of St. Catharines, issued at Toronto

in 1893, "Early Missions in Western Canada," devoted to the labors of

the Recollet, Jesuit and Sulpician missionaries. The labors of these

devoted men are recounted with numerous stirring episodes of life among

the red men, and interesting notes on the customs of the natives.

"Missionary Work among

the Ojibway Indians" was published by Rev. E. F. Wilson, founder of the

Shingwauk Home, Sault Ste. Marie, at London and New York in 1886, and

contains many important facts relating to the language and customs of

the Ojibways, with an account of the progress of religion amongst them.

Interesting memoirs of Father Isaac Jogues, the Jesuit missionary

martyr, have been published in English by the Rev. Dr. Withrow, the

cultured editor of the Methodist Magazine and Review, and author of

several important works relating to Canadian history and European

travel, and in French by the Rev. Felix Martin. This latter work has

been translated into English by Dr. John Gilmary Shea.

Dr. Wrthrow's "Native

Races of North America" (1895) is a small volume treating of the

Cliff-Dwellers, Mound-Builders and Indians of Canada and the United

States. The traditional lore, customs, social and religious burial

rites, and native beliefs of the Indians are well described, and the

progress of the Indians toward civilization, educational effort, and

missionary labors amongst them are told with the pen of a ready writer.

It is an admirable volume, fully illustrated, and cannot fail to delight

and instruct both young and old.

Some interesting

monographs on the missionary martyrs of our country and kindred subjects

have also been published by Dr. Withrow. In the study of biography,

besides the works already mentioned, the student of Canadian Indian

literature cannot afford to neglect Stone's "Life of Chief Joseph Brant"

and "Life and Times of Sir William Johnson."

Many noble poems have

been written upon subjects chosen from the forest and prairie, and the

camp and warpath. Customs, legends and stirring episodes have furnished

fruitful themes for the gifted pens of some of our Canadian poets.

Charles Mair has written an imperishable poem, "Tecumseh." It is a

historical drama, describing the stirring scenes of the war of 1812. The

hero is shown to be a true lover of his people, possessing the qualities

of a great statesman, which were exhibited by his exertions to unite the

red race in a grand federation; and though he signally failed in his

patriotic scheme, he left the impress of his thought upon the native

tribes. In the pages of "Tecumseh " there are many lessons of

patriotism, striking scenes of forest and prairie, and beautiful lines

which stir the imagination and engender thought. Describing the primeval

days of peacefulness on this continent, the author says:

"The passionate or calm

pageants of the skies No artist drew; but in the auburn west Innumerable

faces of fair cloud Vanished in silent darkness with the day, The

prairie realm—vast ocean's paraphrase— Rich in wild grasses numberless,

and flowers Unnamed, save in mute Nature's inventory; No civilized

barbarian trenched for gain.

And all that flowed was

sweet and uncorrupt, The rivers and their tributary streams, Undammed,

wound on forever, and gave up Their lonely torrents to weird gulfs of

sea, And ocean wastes unshadowed by a sail."

The departure of the

soldiers of York for the scene of war in 1812 recalls the Rebellion of

1885:

. . . "On every hand

you see Through the neglected openings of each house— Through

doorways—windows—our Canadian maids Strained by their parting lovers to

their breasts; And loyal matrons busy round their lords, Buckling their

arms on, or, with tearful eyes, Kissing them to the war!

lena the niece of

Tecumseh, as the enemy fires, leaps forward to shield Lefroy, her lover,

and is wounded to death. Lefroy expresses his impassioned grief as

follows:

"Silent forever! Oh, my

girl! my girl! Those rich eyes melt; those lips are sun-warm still,

Millions of creatures throng, and multitudes Of heartless beings flaunt

upon the earth ; There's room enough for them ; but thou, dull Fate !

Thou cold and partial tender of life's field, That pluck'st the flower

and leav'st the weed to thrive— Thou hadst not room for her!"

The poem closes with

these striking lines:

"Sleep well, Tecumseh,

in thy unknown grave,

Thou mighty savage, resolute and brave!

Thou master and strong spirit of the woods,

Unsheltered traveller in sad solitudes,

Yearner o'er Wyandot and Cherokee,

Could'st tell us now what hath been and shall be."

Seventeen pages of

interesting notes explain , the numerous allusions in the poem, and the

impression left upon the mind by the reading of this native historical

drama is vivid and abiding. Lescarbot was the earliest of our Canadian

poets. In his, collection of verses, appended to his "Histoire de la

Nouvelle France," is a poem commemorating a battle fought by an Indian

chief named Memberton and a neighboring tribe. Upon our Canadian shores

Longfellow found a fitting theme for his beautiful poem, "Evangeline,"

and among the Ojibway traditions, the subject matter for "Hiawatha."

J. D. Edgar, M.P.,

published a suggestive tale in poetic form, "The White Stone Canoe; a

Legend of the Ottawas." "Manita," a poem based on an Indian legend of

Sturgeon Point, Ontario, was written by William McDonnell, of Lindsay,

and issued at Toronto in 1888. Charles Sangster and the Hon. Thomas

D'Arcy McGee wrote several poems of native life and customs. The Irish

patriot and poet, deeply lamented as a Canadian statesman, stricken down

in the prime of life by the cruel hand of an assassin, laid at our feet

as his homage to the red men, poems on "The Death of Hudson," "The

Launch of the Griffin," "Jacques Cartier," "Jacques Cartier and the

Child," and "The Arctic Indian's Faith." In the poem on "Jacques

Cartier," after narrating the sorrow of the people of Saint Malo, over

the supposed loss of the brave commodore, and his return, amid the joy

of his townsmen, the land of snow which he had found in the west is thus

described:

"He told them of a

region hard, iron-bound, and cold ; Nor seas of pearls abounded, nor

mines of shining gold ; Where the wind from Thule freezes the word upon

the lip, And the ice in spring comes sailing athwart the early ship ! He

told them of the frozen scene until they thrilled with fear, And piled

fresh fuel on the hearth to make him better cheer."

"He told them of the

Algonquin brave—the hunters of the wild— Of how the Indian mother in the

forest rocks her child ; Of how, poor souls ! they fancy in every living

thing A spirit good or evil, that claims their worshipping. Of how they

brought their sick and maimed for him to breath upon, And of the wonders

wrought for them through the Gospel of St. John.'"

Charles

Sangster'sIndian poem, "In the Orillia Woods," is a native dirge on the

departing race which peopled the County of Simcoe and neighborhood. The

poet drew his inspiration from the great events of our history, and the

striking scenery of forest, lake and river. He published two collections

of verse, "The St. Lawrence and the Saguenay," and "Hesperus, and

other Poems and Lyrics," which were eulogized by the Canadian press and

contemporary poets. A beautiful poem, frequently quoted, upon the names

of places in Acadie and Cape Breton, was written and published by

Richard Huntington, a Nova Scotian poet and journalist. The first verse

reveals the rhythmic beauty of the poem.

"The memory of the red

men

How can it pass away,—

While their names of music linger

On each mount, and stream, and bay?—

While Musquodoboit's waters

Roll sparkling to the main;

While falls the laughing sunbeam

On Chegogin's fields of grain." -

The St. Lawrence and the Saguenay and

other Poems

By Charles Sangster (1856) (pdf)

Miss E. Pauline

Johnson, the gifted daughter of the late Chief G. M. Johnson, of the

Mohawks, has won favor by the artistic rendition of her poems on the red

men. She has appeared as the poet-advocate of her race, and especially

of the Iroquois. "The White Wampum" is a quaint-looking little volume of

Indian verse, imaginative and descriptive, with a richness and beauty

that is entrancing. Some of her poems are gems, and, when recited by

Miss Johnson in her Indian costume, produce a thrilling effect. The

following poems portray all the passion and romance of her race: "The

Avenger," "Red Jacket," and "The Cry of the Indian Woman." The

canoe-song, "In the Shadows," is a fine specimen of her poetic

utterances:

"I am sailing to the

leeward,

Where the current runs to seaward,

Soft and slow; Where the sleeping river grasses

Brush my paddle as it passes To and fro.

PAULINE JOHNSON, IN INDIAN COSTUME.

"On the shore the heat

is shaking,

All golden sands awaking

In the cove; And the quaint sand-piper, winging

O'er the shallows, ceases singing When I move.

'On the water's idle

pillow

Sleeps the overhanging willow

Green and cool; Where the rushes lift their burnished

Oval heads from out the tarnished Emerald pool.

'Where the very water

slumbers,

Water-lilies grow in numbers,

Pure and pale; All the morning they have rested,

Amber-crowned and pearly-crested— Fair and frail.

Here, impossible

romances,

Indefinable sweet fancies,

Cluster round; But they do not mar the sweetness

Of this still September fleetness With a sound.

I can scarce discern the

meeting

Of the shore and stream retreating,

So remote; For the laggard river, dozing,

Only wakes from its reposing Where I float.

Where the river mists

are rising,

All the foliage baptizing

With their spray; There the sun gleams far and faintly

With a shadow soft and saintly In its ray.

And the perfume of some

burning

Far-off brushwood, ever turning To exale;

All its smoky fragrance, dying,

In the arms of evening, lying, Where I sail.

"My canoe is growing

lazy,

In the atmosphere so hazy,

While I dream; Half in slumber I am guiding

Eastward, indistinctly gliding Down the stream."

Arthur Weir's

"Champlain," "The Captured Flag," "The Priests and the Ministers," and "L'Ordre

de Bon Temps:" Matthew Richey Knights' "Glooscap" and "The Dying Chief;"

Mrs. S. A. Curzon's "Laura Secord" and "Fort Toronto," and George

Martin's "Marguerite," "The Heroes of Ville Marie," and "Changes on the

Ottawa," bring vividly before the mind scenes of other days when the

moccasined foot of the warrior trod gently upon the forest trail, and he

welcomed to his sorrow the pale-faced heir of civilization, who claimed

at last the red man's heritage as his rightful possession.

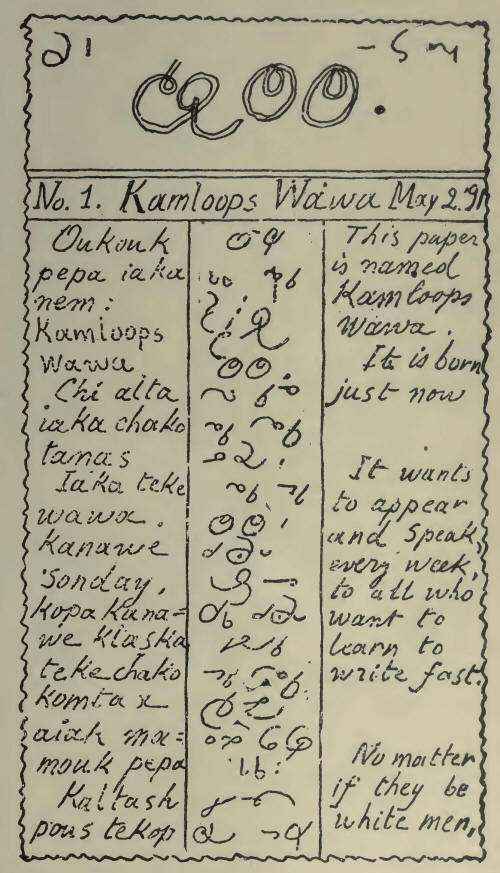

Of newspapers and

magazines a few have appeared in the interest of our Canadian Indians:

Petaubun (Peep o' Day), a monthly periodical, was published at Sarnia in

1861 and 1862, by the Rev. Thomas Hurlburt. Three pages were printed in

the Ojibway and one in the English language. The Pipe of Peace was

published in 1878 and 1879, at Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, by the Rev. E.

F. Wilson, of the Shingwauk Home. The first numbers were printed in

Ojibway and English, and the later issues in Ojibway. After the

suspension of this paper Our Forest Children was begun, the first copy

being issued by Mr. Wilson from the Shingwauk Home in 1887. This also

was discontinued, but was immediately followed in 1890 by The Canadian

Indian, with the Rev. E. F. Wilson and Mr. H. B. Small as editors. It

was published under the auspices of the Canadian Indian Research

Society, and existed for two years. The two latter publications were

printed in English for the purpose of awakening an interest in the

Indians and aiding in the investigation of the folk-lore, languages and

customs of the natives and Canadian archaeology. The Indian was issued

as a bi-monthly paper "devoted to the Indians of America," by Chief

Kahkewaquonby (Dr. P. E. Jones), in 1885. The office of publication was

located at Hagersville, Out., in close proximity to the Six Nation's

Reservation 011 the Grand River. For a short time the paper was issued

weekly, but, like all its predecessors, it ceased to exist within two

years, twenty-four numbers being published.

An occasional paper,

The Aboriginal, was published in New Brunswick, containing notes on the

customs of the Indians. The Young Canadian, a weekly magazine, devoted

to the youth of our Dominion and intended to foster a national pride in

Canadian progress, history, manufactures, science, art and literature,

was issued at Montreal in 1891, with Margaret Poison Murray as

editor-in-chief. Interesting tales of our early history and stories of

Indian life, profusely illustrated, adorned its pages, but apparently

through the influence of the literature of our Great Neighbor and our

limited constituency it failed to win the needful support. Canada was

another patriotic magazine of excellent merit similar in its aims to The

Young Canadian, whose pages were filled with tales and poems from some

of our best writers. Interesting stories and essays on native life and

customs have appeared frequently in the Methodist Magazine and Onward,

under the able supervision of the Rev. Dr. Withrow. The Canadian

Magazine, Manitoba Free Press, Pilot Mound Sentinel, and the Proceedings

and Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, Canadian Institute,

Hamilton Association, Montreal Folk-Lore Society, Quebec Historical

Society, Manitoba Historical Society, Nova Scotia Historical Society,

Ottawa Literary and Scientific Society, Wentworth historical Society,

Elgin Historical and Scientific Institute, Institut Canadien-Francais

d'Ottawa, Socidte His toriclue de Montreal, and other societies in the

Dominion supply valuable papers 011 the early history of the nation and

on the legends, customs, languages and beliefs of the Canadian red men.

Our leading writers

upon the Algonquin and Iroquoian languages are Horatio Hale, A. F.

Chamberlain and the Abbd Cuoq. The Rev. Dr. John Campbell, of Montreal,

has discussed some of the comparative features of these languages with

the Japanese, Basque and Peninsular languages in his interesting papers,

"On the Origin of Some American Indian Tribes," "The Hittites in

America," "The Affiliation of the Algonquin Languages," "Asiatic Tribes

in North America," "Some Laws of Phonetic Change in the Khitan

Languages," and "The Khitan Language; the Aztec and its Relatians." The

Abbe J. A. Cuoq has written an appendix to his Algonquin grammar under

the title, "Anotc Kekon," which appeared in the eleventh volume of the

"Proceedings and Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada,"

containing valuable reflections on the folk-lore and literature of the

Algonquins, notes on the history of the mission of the Lake of Two

Mountains, and a discussion of the gram-matie contents of the language,

with examples of familiar phrases, the divisions of time and natural

history. There has also appeared, in the French section of the

"Transactions," his "Algonquin Grammar." It is a compact, clear,

well-arranged and comprehensive grammar, showing the intricacies of the

language in its numerous forms, sufficiently explained and definite as

to enable the student to master its difficulties. Our first scholar of

the Huron tongue was the Jesuit martyr, John de Brebeuf. In one of his

"Relations" there is a treatise on the Huron language, which has been

republished in the "Transactions of the American Antiquarian Society."

He wrote a grammar of the language, which has never been published.

Several treatises on the Micmac language have been published separately

and in conjunction with books of travel. A grammar of the language was

published in England by an unknown French author, fragments of which

have been preserved. The Abbd Maillard left among his manuscripts a

Micmac grammar, which was published at New York in 1864. The author was

an able scholar, who came to Canada about 1738, and was appointed

Vicar-General of Acadia. He labored among the Indian tribes and in the

Acadian villages in Cape Breton and on the coast of Miramichi. After

many years of great hardship he died at Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1768.

Father Jacques Bruyas, Superior of the Iroquois mission, left among his

papers "Radices Verboriun Iroqiunorum," containing a grammatic sketch

and dictionary of the Mohawk language, written in Latin, with the

meaning of the words in French. This treatise was published in 1862, in

New York, and is one of the volumes of Shea's Library of American

Linguistics. The author was a master of several of the dialects of the

Iroquois. He came to Canada in 1666, and died at the mission of Sault

St. Louis, on the St. Lawrence, in 1712. A grammar and dictionary of the

Ojibway language was published at Toronto in 1874, by the Rev. E. F.

Wilson, of Sault Ste. Marie. Manuscript treatises and grammars I of the

Micmac, Montagnais, Ojibway and Huron languages are I extant, but some

of the most notable manuscript volumes I referred to in the writings of

the early missionaries and travellers have been lost. A curious mosaic

is the work of the Jesuit missionary, Stephen de Carheil. His " Radical

Words of the ' Huron Language," forms two small duodecimo manuscript

volumes in Latin, French and Huron. Of the author it is said, "As a

philologist he was remarkable. He spoke Huron and ' Cayuga with the

greatest elegance, and he composed valuable works in and upon both, some

of which are extant." Chau-inonot's grammar of the Huron language was

found among his papers and translated by John Wilkie, from the Latin.

Gar-nier's Huron grammar, in manuscript, is lost, as are also Lale-I

mant's "Principles of the Huron Language," Wood's grammar of the Micmac,

and Father Robert Michel Gay's "Grammar Algonquine." A "Grammaire

Algonique," in manuscript, is preserved in the Biblioteca Vittorio

Ennnanuele, at Rome, whiclr is the work of the Abbe Thavenet, and a

manuscript translation of this work is preserved among the papers of the

world's greatest linguist, Cardinal Mezzofanti, in the Biblioteca Com-munale,

at Bologna. Potier's " Grammar of the Huron language" and other essays

on the languages of the Canadian Indians are in the possession of

private persons.

The first dictionary of

the native languages of Canada was < the Huron, prepared by Father

Joseph Le Caron. Le Clercq says of this work and its author: "The

dictionary of the Huron language was first drafted by Father Joseph Le

Caron in 1616. The little Huron whom he took with him when he returned

to Quebec, aided him greatly to extend it. He also added rules and

principles during his second voyage to the Hurons. He next increased it

by notes, which Father Nicolas sent him, and at last perfected it by

that which that holy monk had left when descending to Quebec, and which

the French placed in his hands; so that Father George, procurator of the

mission in France, presented it to the king with the two preliminary

dictionaries of the Algonquin and Montagnais languages in 1625." Father

Gabriel Sagard's dictionary of the Huron language was published at Paris

in 1632. Of the language of the Gaspesians, Christien Le Clercq,

inventor of the Micmac hieroglyphics, has given some general remarks in

" Nouvelle Relation de la Gaspesie," published at Paris in 1691. Father

Sebastien Rasles left a valuable manuscript dictionary of the Abnaki

language, which was not published till 1833. The dictionary is in French

and Abnaki, and contains an introductory memoir and notes by John

Pickering, A.A.S. In the supplementary notes and observations by Mr.

Pickering there are extracts from Father Rasles' letters, a description

of the original manuscript, the alphabet used by the author, and

comments upon the Abnaki and cognate dialects. The following account of

Father Rasles and his work is given in the notes .and observations:

"Father Rasles, in one

of his letters, dated at Nanrantsouak (Norridgwock) the 12th of October,

1723, and published in the Lettres Edifiantes, makes the following

general remarks upon the Indian languages and his mode of studying them.

"'On the 23rd of July,

1689,1 embarked at Rochelle, and after a tolerably good voyage of about

three months, I arrived at Quebec the 13th of October of the same year.

I at once applied myself to the study of the language of our savages. It

is very difficult, for it is not sufficient to study the words and their

meaning, and to acquire a stock of words and phrases, hut we must

acquaint ourselves with the turn and arrangement of them as used by the

savages, whieh can only be attained by intercourse and familiarity with

these people.

"'I then took up my

residence in a village of the Abnaki Nation, situated in a forest, which

is only three leagues from Quebec. This village was inhabited by two

hundred savages, who were almost all Christians. Their huts were in

regular order, much like that of houses in towns; and an enclosure of

high and close pickets formed a kind of bulwark which protected them

from the incursions of their enemies.....

"'It was among these

people, who pass for the least rude of all our savages, that I went

through my apprenticeship as a missionary. My principal occupation was

to study their language. It is very difficult to learn, especially when

we have only savages for our teachers.

"'They have several

letters which are sounded wholly from the throat, without any motion of

the lips, ou, for example, is one of the number; and, in writing, we

denote this by the figure 8, in order to distinguish it from other

characters. I used to spend a part of a day in their huts to hear them

talk. It was necessary to give the closest attention in order to connect

what they said, and to conjecture their meaning. Sometimes I succeeded,

but more frequently I made mistakes;. because, not having been trained

to the use of their gutturals, I only repeated parts of words, and thus

furnished them with occasions of laughing at me. At length, after five

months constant application, I accomplished so much as to understand all

their terms; but that was not enough to enable me to express-myself so

as to satisfy their taste.

"'I still had a long

progress to make in order to master the turn and genius of their

language, which are altogether different from the turn and genius of our

European languages. In order to save time, and to qualify myself to

exercise my office, I selected some of the savages who had the most

intelligence and the best style of speaking. I then expressed to them in

my rude terms some of the articles in the catechism; and they rendered

them for me with all the delicacy of expression of their idiom; these I

committed to writing immediately, and thus in a short time I made a

dictionary, and also a catechism, containing the principles and

mysteries of religion.'"

The Jesuit missionary

Pierre Laure prepared, in 1726, a dictionary of the Montagnais language.

In recent years there have appeared an Ojibway dictionary, now out of

print, by Peter York, an Indian belonging to the County of Simcoe; an

Algonquin dictionary in the Frendh language, by the Abbe J. A. Cuoq ;

and a Lenape-English dictionary, compiled from .anonymous manuscripts in

the archives of the Moravian Church at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, by Dr.

D. G. Brinton, of the University of Pennsylvania, and the Rev. Albert

Seqaqkind Anthony, assistant to the Delawares and Six Nations in

Ontario. Dictionaries in manuscript of the Huron language are to be

found among the archives of Laval University, and at Lorette. One of

these is attributed to Brebeuf, another to Chaumonot, and the others are

by authors unknown. A Mohawk dictionary in manuscript, written by La

Gallissouniere, is deposited in the Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris.

Dictionaries in manuscript of the Seneca, Abnaki, Algonquin, Ojibway,

Ottawa and Montag-nais languages are to be found among the archives of

the Catholic churches at Caughnawaga, Pierville and Lake of Two

Mountains; Laval University, Quebec, and McGill College, Montreal, and

in the possession of private individuals.

There are extant

numerous vocabularies of the native languages. Our first published

vocabulary was that of Jacques Cartier, in 1545, who left us some

specimens of the language of the extinct Hochelagans. Some of these

vocabularies are to be found in books of travel and scientific

magazines, but the greater part of them remain in manuscript deposited

in the archives of churches, colleges, public libraries, historical

societies and private persons. Vocabularies of the following languages

spoken in the Dominion are known *to exist: Mohawk, Micmac, Seneca,

Cayuga, Oneida, Onondaga, Tuscarora, Algonquin, Nanticoke, Shawnee,

Abnaki, Mississauga, Ottawa, Acadian, Munsee, Nipis-sing, Penobscot and

Pottawotomi.

Legends and folk-tales

from the Cayugas, Onondagas and Tuscaroras, songs of the Abnakis, and

legends of the Ojibways, Micmacs, and Passamaquoddies have been

preserved. Some of these are extant in the native tongue and others in

translations.

"A Sacred History," in

manuscript, in the Mohawk language is among the archives of the Roman

Catholic Church, at Caugh-nawaga, and a "History of the People of God,"

in the same language, beautifully written and well preserved, in two

volumes, is among the archives of the Catholic Church at the Lake of Two

Mountains. Both of these works were prepared by the Abbe Terlaye, who

was a missionary at La Galette and Lake of Two Mountains. He died at the

latter place May 17th, 1777, and was buried here. Of lesser works in the

native languages worthy of notice are the "Autobiography of

Kaon-dinoketc," "A Nipissing Chief," "The Story of the Young Cottager,"

in Ojibway; "The Only Place of Safety," in Micmac; and several tracts by

F. A. O'Meara and James Evans.

Nearly the whole of the

Bible has been translated into the Ojibway and Micmac. The New Testament

has been translated in the Ottawa and Mohawk, and portions of the

scriptures in Iroquois, Delaware, Abnaki, Maliseet, Shawnee, rottawotomi,

Huron and Seneca. The leading translators of the scriptures have been

Dr. S. T. Rand, Chief Joseph Brant, Chief Joseph of Oka, J. Stuart, B.

Freeman, H. A. Hill, J. A. Wilkes, W. Hess, T. S. Harris, A. Wright, F.

A. O'Meara, Peter Jones, James Evans, J. Lykins and C. F. Dencke.

Catechisms have been

prepared for the use of the Algonquin, Ojibway, Micmac, Nipissing,

Ottawa, Munsee and Abnaki Indians.

Prayer books, including

the Roman Catholic and Anglican Book of Common Prayer, have been

translated into the languages of the Mohawk, Algonquin, Ojibway, Ottawa,

Micmac, Munsee, Nipissing, Maliseet, Penobscot and Passaniaquoddy

tribes.

It is a singular fact

that almost the first printed book in the United States and Canada was

for the use of the Indians. John Eliot issued his "Massachusetts

Catechism " about 1654, and in 1767 Father de la Brosse published the

"Roman Catholic Prayer Book, and " A Primer of Christian Doctrine, at

the press of Brown and Gilmore, of Quebec, in the language of the

Montagnais Indians. " The Anglican Book of Common Prayer" was printed at

the same press, in 1780, in the language of the Mohawk Indians, and at

the expense of the Government. The first printing press in Canada was

established by Bushel in 1751, in Halifax, Nova Scotia, who, in January

of the following year published the first Canadian Gazette.

William Brown and

Thomas Gilmore introduced printing into the Province of Quebec in 1763,

and on June 21st, 1764, issued from the press at Quebec the first number

of the Quebec Gazette in French and English. Several little quartos on

French law were published by Brown in 1775; but the first known Canadian

book was a catechism by Archbishop Languet, issued in 1765.

Hymn books have been

prepared in nearly all the languages mentioned above, which are used by

the missionaries and people. Sermons, Scripture narratives, calendars,

Bible histories, reading books and spellers, and even a work on church

polity have been translated for the use of some of the tribes. Some of

these have been published, but the most of them remain in manuscript. In

this sketch of the literature relating to the Indians of Ontario,,

Quebec and the Eastern Provinces, the reader cannot fair to be impressed

with the heroic labors of the men who have devoted' their lives to the

work of elevating and saving the aborigines-of our land. Amid great

privations they toiled, persecuted' sometimes by their flock, burdened

with the indifference of their dusky followers, and opposed by their

white brethren, and in the gloaming of life they were happy, if they

beheld an humble, mission-house and church, and a handful of faithful

disciples. Many of them were men of great learning and of gentle births

who might have shone as statesmen or ruled as wealthy merchants ; but

they rejected wealth and fame, and labored with intense devotion for the

sake of a few red men. We have forgotten these heroes of our country,

whose delight was to toil and suffer for others, and their very names

sound strangely in our ears, but they won in life's contest, and in

their death they were more than conquerors.

THE SIGN LANGUAGE

Sign language is

sometimes called gesture speech, as it is a method of conversing by

means of gestures or signs. It is a form of speech in use among

civilized and savage races, which is perfectly understood, and although

greatly limited in its forms of expression by those who have a spoken

language, rich in its vocabulary and possessed of an extensive

literature. It is properly designated a language, as among savage races

it has various conventional forms, which are in a measure definite and

full. As a language it is divided into facial expression and

conventional forms. The expression of the faces of individuals is

sometimes concealed, as among certain tribes of Indians, by the paint

which they use, but when not thus concealed the emotions can easily be

detected. The movements of the face are developed by the growth of the

mind, which calls new feelings into existence. These movements are the

result more especially of the emotions. The instinctive or voluntary

play of the features express the feelings, as is shown by babies, who

are able to read the expression of the countenances of persons, and can

tell their intention toward them.

Facial expression is so

complete that instances are known where conversation has been carried on

by its use alone. Tribes of Indians are known who are able to state

clearly their ideas by means of this play of features. Corporeal motions

express operations of the intellect as distinct from facial expression.

These corporeal gestures are not only used by man, but are in use among

animals. These gestures or signs have become conventionalized, and

amongst certain tribes definite.

Animals use sign

language as a mode of communication.

George Romanes says:

"The germ of the sign-making faculty occurs among animals as far down as

the ant, and is highly developed among the higher vertebrates. Pointer

dogs make signs, terriers 'beg' for food, and the cat, dog, horse and

other animals make signs. The animal is capable of converting the logic

of feelings into the logic of signs for the purpose of communication,

and it is a sign language as much as that of the deaf-mute or savages."

Sign language is in use

amongst civilized races to a limited degree even at the present day.

When we nod the head to mean "yes" or shake it to mean "no," and when we

join hands in token of friendship, we are using gesture language. If we

were travelling among a people whose language we did not know we should

be compelled to resort to this method of making ourselves intelligible

more extensively.

In the Lowlands of

Scotland the boys have a game resembling the pantomimes of the ancients,

which were performed by persons who uttered no words,'but imitated the

acts of the persons represented.

In the earliest stages

of the human race, when words were short and few, sign language must

have been used extensively -as an aid to the primitive form of speech;

and when tribes and races were developed, it must have been employed in

conversing with those ignorant of each other's language.

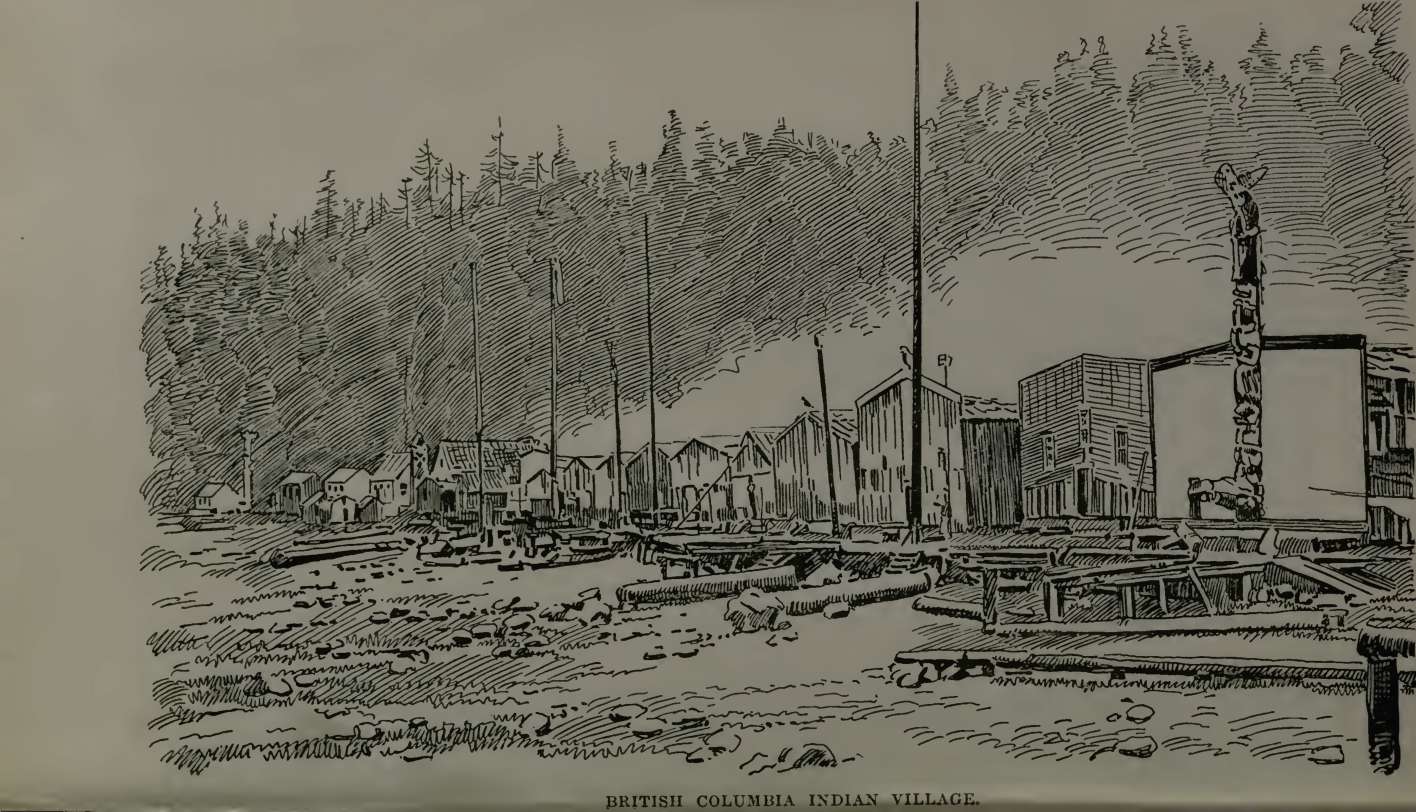

The languages of the

tribes of British Columbia and other parts of Canada are emphasized and

their meaning made clear by the use of intonation and sign language, By

laying stress upon a syllable words are made to have different meanings.

I found a striking illustration of this when I was learning the

Blackfoot language among the Blood Indians. Being desirous of learning

the whereabouts of a friend, who was a member of the Mounted Police, and

was known among the Indians as the man who sews," he being by trade a

tailor, I said to one of my Indian companions, "Tcima Awateinake?" but

he did not nnderstand me. Again I essayed "Tcima Awateinake?" but he

only shook his head. Finally I asked "Tcima Awateinake?" and he smiled

and gave me the needful information. The question I asked him was,

"Where is the man who sews ?" In the Chinook jargon not only is this

expressive intonation in use, but gesture are employed to enlarge the

meaning of some of the words. Thus "kuatan" means "a horse," but "riding

on horseback " is expressed by using the word and the gesture sign for

riding.

Many of the gestures of

the sign language are understood by deaf mutes, but not all, as even the

deaf mute language is not definite, many conventional terms being

employed in America which are not in use in Europe; and, indeed,

differences exist among the several institutions for deaf-mute

instruction upon the American continent. Although my personal knowledge

of the sign language is quite limited, I have conversed intelligibly for

a short time with a deaf mute whom I met at Calgary.

The language of

gestures is not confined to the Indian tribes, but traces of its

existence have been found in Turkey, Sicily, the Hawaiian and Fiji

Islands, Madagascar and Japan. Collections of signs of great value have

been obtained from some of these countries. An exhaustive collection has

been obtained from Alaska. These collections go far to prove the

existence of a gesture speech of man. We are chiefly concerned, however,

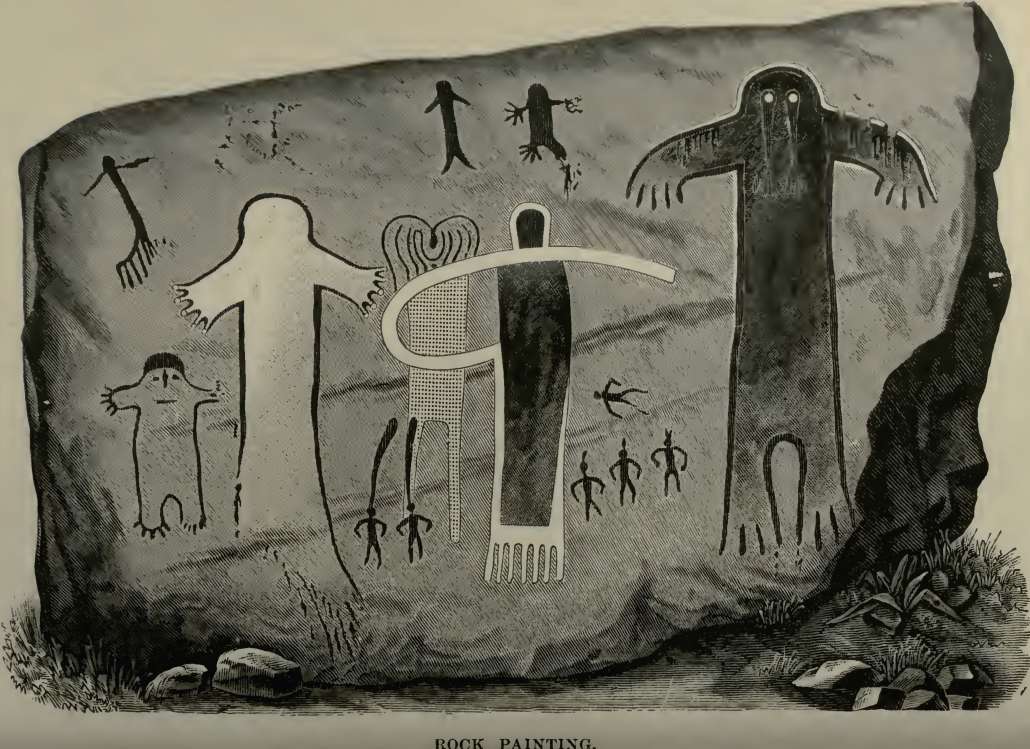

with this form of speech among the American Indian tribes. It has been

systematized among some tribes into picto-graphs, which comprise a

native system of hieroglyphics. These pictographs are the visible

representation of the gestures. These are found painted on the face of

cliffs in some of the strangest places, seldom visited by the white man,

upon the walls of caverns, on buffalo robes and the skins of other

animals, the lodges of the Plain Indians and birch-bark rolls, and some

are even carved on walrus ivory by the tribes of the far north,

especially among the Alaskan Indians. Human figures are drawn in the

attitude of making gestures. Nome-times the differences in the color of

the different persons represented is significant, and is used as an aid

to the interpretation of the gestures. For example, the symbol of

peace is the

approaching palms of two persons, and in order to distinguish them from

the approximation of the palms of one person, the arms are painted in

different colors. In a hide painted for me by a Blood Indian, which

contained the record of the chief exploits of his career very fully

depicted, and with some degree of artistic skill, several of these signs

appear.

There is a general

system of gesture speech among the Indian tribes, but it is not to be

regarded as a formal or absolute language. Whilst there exists a

similarity between some signs, and there are some that are in common use

among all the tribes, still there is a diversity which reveals centres

of origin, and it would be impossible to prepare a vocabulary that would

be sufficiently definite as to be understood. As there are differences

in spoken language so are there diversities in sign language. The

investigations of Colonel Mallery and Dr. W. J. Hoffman have been

continued for several years upon this subject, and have covered a large

number of Indian tribes, and included foreign countries, and the result

of their united labors have .shown that there are certain groups of

tribes which form centres of origin of the sign language, and that some

signs have become so conventionalized as to have a definite meaning in

one group or tribe which they do not possess in another. It is not a

universal language in the sense of being understood by all the tribes,

and still the ideographic signs may be so interpreted. Gesture language

has been divided into five groups, as follows: First, the Arikara,

Dakota, Mandan, Gros Ventre or Hidatsa, Blackfoot, Crow and other tribes

in Montana and Idaho; second, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Pani, Kaiowa, Caddo,

Wichita, Apache of Indian Territory, and other tribes in the South-West

as far as New Mexico, and possibly portions of Arizona; third, Pima,

Yuma, Papago, Maricopa, Hualpai (Yu-man), and the tribes of Southern

California; fourth,4Shoshoni, Banak, Pai Uta of

Pyramid Lake, and the tribes of Northern Idaho and Lower British

Columbia, Eastern Washington, and Oregon; fifth, Alaska, embracing the

Southern Eskimo, Kenai, (Athabascan), and Iakutat and Tshilkaat tribes

of the T'hilin-kit or Koloshan stock.

Sign language is used

extensively by the plain tribes of our Canadian North-West. The tribes

located in Ontario and Quebec seldom use it, which may arise through

their contact with civilization and their imitation of the habits and

customs of the white race. Indeed, the gestures employed by the Iroquois

are so few that they need not be classified, and the same may be said of

the tribes of British Columbia, who possess a sign language, but not

sufficiently extensive for classification. Among some Indian tribes the

system of gesture speech is so well defined that conversation can be

carried on by means of it alone. Indeed, several instances have been

known where conversation has taken place by means of the gestures of the

face, and without the aid of the hands, which shows the possibilities of

intellectual expressions of the face as well as emotional. The use of

this language has been kept up amongst the savage tribes more than

others, on account of their surroundings. Accustomed to live in

situations where noise is dangerous, lest they might alarm their warlike

foes, the gesture speech has been preserved as a useful adjunct to

spoken language North Axe, a Piegan Indian chief, residing on his

Reserve, which is located in Southern Alberta, as he lay at the point of

death unable to speak, gave instructions to the Indian agent to send his

son and brother to the Brantford Institute to be educated. His wishes

were conveyed by means of signs. Upon the same Reserve, during my

residence in that part of the country, there lived two boys and a girl,

deaf and dumb, who were able to converse with their companions and

friends by signs. Kutenaekwan, a Blood Indian, was so badly shattered

with gun-shot wounds that he was unable to hear or speak ; yet I have

watched him for hours telling his friends the great exploits of his

life. As he became excited with his narrations, his friends grew

enthusiastic and encouraged him to continue his story.

A few of the gesture

signs may be given to show the use made of them in expressing the ideas

and emotions of the natives. Anger is almost always betrayed by the

eyes, fear by the dirty greyish color of the skin, and surprise by

suddenly drawing in the breath, as if gasping. I have seen the natives

when astonished—the astonishment arising from sad news or a message of

joy—place the hand upon the mouth, covering it. Usually, if not always,

the palm of the right hand is placed over the mouth to signify

astonishment. The Apaches rarely point to an object with the finger, but

raise the chin and point the lips toward it. In calling the attention of

a person at a distance, the right hand is raised at arm's length above

the head, with the fingers extended, and the hand moved quickly backward

and forward from the wrist, the arm remaining motionless. An Indian

riding upon the prairie will stop when he sees a man perform this sign.

Should the man wish the horseman to come to him, he will sway the hand

with the palm facing the ground, the whole arm from the shoulder

performing a forward and downward motion, till the hand reaches the

knees. This will be repeated two or three times, till the rider sees

distinctly what is intended. Walking along the Reserve one day I was

anxious to speak to a white man who was half a mile distant, and was

walking in the opposite direction, so that he was beyond the reach of my

voice. Owing to the voices of children and the rushing of the water in

the river, I could not make myself heard by any natural or artificial

call. Beyond the white man was an Indian on foot coming toward me, and

not far from my friend. One of the Blood Indians standing beside me came

to my rescue, and making the sign to the Indian at a distance to arrest

his attention, told him in the sign language to inform the white man

that he was wanted. The Indian meeting my white friend told him the

result of the conversation, when he suddenly turned around and walked

back to the place where I was waiting for him. This is one of the

methods of what might not be inappropriately termed the native system of

telegraphy. Signal fires, different methods of riding on horseback,

signs made with blankets and stones, and the striking use of the

looking-glass make up a very effective system of communication at a

distance upon the prairie. The sign for rain is made by holding the

hands in front of the shoulders, the fingers hanging down to represent

the drops. Lightning is represented by pointing the forefinger of the

right hand upward, and bringing it down with great rapidity, with a

sinuous motion, showing the course of the lightning.

Various signs are used

to distinguish the tribes. The sign for the Blackfeet is, the right hand

closed, the two forefingers extended, and the hand pushed outward and

downward over the right foot. The sign for the Piegans is made by

closing the right hand, and the fist, with the thumb toward the face,

revolving quickly over the upper extremity of the right cheek-bone, with